Diary Dearest by Tom Chomont

Diary is an integral aspect of most filmmaking, because unlike other forms of art, the filmic image is rendered from a recorded likeness, however altered or unrecognizable it may become. The diary aspect may or may not be apparent to viewers, but there is an indelible relation between the film and the maker. With the camera prosthesis, each act of seeing requires a frame which necessarily excludes more than it embraces. These rectangles of intention, these dividing lines between the visible and invisible world, are also a part of each maker’s personality, a signature of seeing.

June 27, 1992

There is a place from which all emanates, that is all light and all sound in harmony, and this light is shaped to our own individual experience, projected onto worldly matters. Pure light and sound is the beginning and the end, but short of that are the infinite heavens and hells that we make of it. (Is all action reaction?)

This preceding paragraph is based on a memory of reverie while riding the Enterprise at Coney Island. The open cart is spun along the ground, and then the carousel tips and the cart hurls up to the sky, then back down to the earth in a continuing circle. This describes in my mind, the space between that very inner private chamber and the earthly domain, the vertiginous path between heaven and earth taking place at every moment. For heaven can just as well be hell. I sense the internal space of my mother, Peter, all who I have known and who have known me, separated forever as individuals by the borders of our limited identity. I know the cart will return to earth but I will disembark into a world plainly shaded by own private approach.

Quite suddenly, after not seeing much of each other, and me quite inconsolably sad, Clark and I decided to live together. Much uncertainty, unspecified directions, undefined situation. Currently unspeakably happy.

My initial impulse to film was intimately bound to creating souvenirs of moments, people, places, objects, feelings, enactments and the like. This was motivated by the desperate realization, already at the age of five, that all things were subtly but surely changing and that no moment could be re-experienced. This was followed by the more disturbing realization, around age ten, that even the most vivid memory grew dimmer and less detailed, and that subtle but unstoppable changes in who ‘I’ was made it impossible to even go on recapturing the past even with the literal evidence of a photographic likeness to preserve it. But I was simultaneously becoming aware of the power of artistic means to render something transmutable. Each moment, as it is lived, dies instantly, or with the trailing blaze of a shooting star, but art held out the possibility that something of that past could be propelled forward by an alteration of form.

Nov. 28, 1995

The day before Thanksgiving Clark and I went to an anniversary party at an S/M bar. I had a design drawn on my chest after Clark put a dog collar on me. Then my head was shaved (and my pubic hair) by a barber dressed in leather chaps with a black rubber jock. We ran into a friend who was in the ‘adult video’ I did in 1991. (just sold a re-edited, harder version to a distributor.) A friend of his said, “Hello,” and without another word began to pinch him by the nipples, bringing him to his knees, at which point Clark and I grabbed his arms and legs, stretched him over another man’s knees, pulled down his pants and slapped and strapped his ass. All four of us took turns, and then Clark got some ice cubes from the bar and cooled down his butt before shoving the ice in. The day after Thanksgiving he came over for a take-out dinner to talk about shooting another video at his house in West Virginia…

Image gathering always has a sentimental aspect for me, though the final form of a work requires a merciless rending of the material. Even my most apparently confessional and/or anecdotal works, such as Phases of the Moon (1968), Oblivion (1969), Razor Head (1984) or The Dog Diary (1996), are far from literal records.

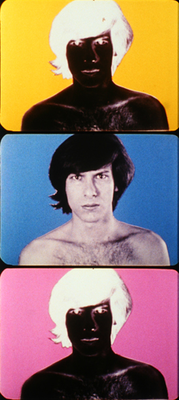

*While I was making Morpheus in Hell (1967) I was working as a typist in an office. I began to feel like a machine, and developed mechanical rhythm periods in my sleep that were like dreams, and then eventually even when I was awake I would sometimes see landscapes and faces in front of me when I closed my eyes. We would be talked into working until two or three in the morning one night a week when the deadline came due. Once, I came home and stood in front of the mirror, talking to myself, saying things I didn’t even know. The odd thing was that I experienced both talking and listening to the face in the mirror. Sometimes I would look at the face and see the lips moving and hear the words coming like they were someone else’s. That was the beginning of Phases of the Moon, which was shot in the same mirror, and explores the divide in our personalities. But I soon realized that two wasn’t enough, it’s really millions, because all the faces are us, and we have to split into more than two. We have to keep splitting until we know all of them.

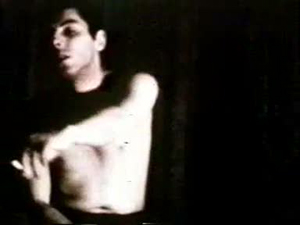

I’d lived almost a year near Central Park West and never realized it was a gay cruising area, and then one night I was walking and suddenly noticed men looking at me. My mouth just dropped open. I was aroused! One man approached me and I must have looked petrified. I immediately felt he was a hustler. I was afraid to bring him to my room, but I finally relented. I knew him for over a year on and off; he would disappear and come back, and that’s how Oblivion began. It was shot on two separate evenings, but had elements of many of our visits. We would sit and talk, he would smoke, and at some point one or both of us would feel aroused. Usually he would take off his shoes when he wanted to have sex; that’s in the film where his hand untying his shoe is blended with a pan of his body on the bed. While this material was highly personal, I was conscious from the beginning that there had to be a formal side. The experiences themselves had broader meanings of identity and role-playing and the face as a mask. I wanted to give the film the feeling of being between dreaming and awake. Much of the imagery had symbolic meanings for me, like the apple, and the canopy of lights which I thought of as the nervous system or the circulatory system.

There’s always a tension for me between the fact of seeing someone from the outside—as a body, an object—and seeing the identity dissolution that usually takes place during sleep. If it happens when we’re awake, it’s disturbing; we want to avoid it. But objectifying him was a tendency in our relationship because he took so many drugs. At that time, I think he had trouble accepting his sexuality. He said it was easier to accept performing sexual acts for money, but the fact of the matter was, he would sometimes take the money he earned and go buy another prostitute to have sex with him as he wanted it. Twice he asked me to pay him for sex and I thought, “This is a very bad precedent and besides I can’t afford it.” While I resisted, it still appealed to me to ask, “What will you do for this much?” After many years of trying to follow what I was taught—not to do certain things sexually—I had a lot of very intense fantasies. During this time I began to act out my fantasies, and, in doing so, the experience became more important than the fantasy. This all became part of the film.

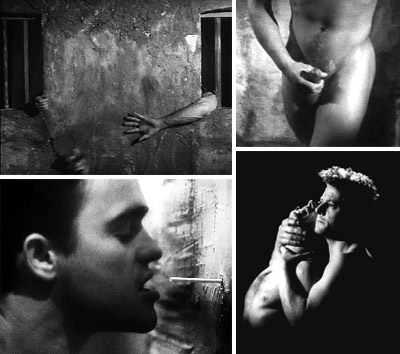

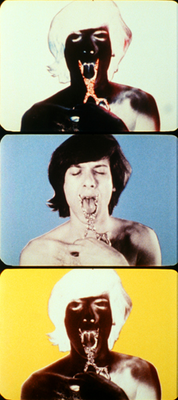

“Approximately thirty images comprise Oblivion. Most obsessively repeat themselves. Although the images appear to be solarized, the film was actually contact-printed, combining high contrast black and white negative with a colour positive of the same image. The high contrast accounts for the tendency of shots to flood. Images in the film swell and contrast, often disappearing into pure colour… Oblivion employs extremely rapid cutting. Some of the images last as briefly as two frames. The fact that we see so few frames, that a shot is representationally ambiguous, or shown upside down and sideways, often causes the viewer to project his/her own fantasies… When Jean Genet was asked to what end he was directing his life he responded, “To oblivion.” (J.J. Murphy, “Reaching for Oblivion”)

July 23, 1996

July 4th weekend turned out to be a crisis point in my relationship with Dog. I had pushed Dog into a three-way relation with Clark and I, and he began to feel that he was in the middle of our relationship. Just at that point he was obliged to go to Washington to help an ex-lover pack and move to New Jersey. I became insecure, although he assured me it was just an old personal debt with very bad timing. Finally, I realized he wanted to feel I was taking a decisive role and wanted him as my Dog. And I did! He had to go to California again this week for more training. Clark thinks he may be a stray Dog, I’m inclined to feel he is a faithful Dog. I’ve done unsafe things with both Clark and Dog. Keep both informed what is going on. But, does Dog keep me informed? The insatiable appetite for Dog is on hold, I probably needed the rest. Miss him, trust him. We had a great time before he left.

The film diary questions the relation between reality and illusion in art. For instance, some viewers understand The Dog Diary (1996) as literal documentation. But while it is based on video material gathered during several days over a six week period, the original recordings run over five hours, and the finished tape is just twenty two minutes. Alongside montage and several video ‘effects,’ it also features superimposed sounds and pictures. In its finished version, it has a closer approximation to memory than the original footage. The largely erotic relationship with Dog was based on sexual fantasy, and the tape works to convert some of these moments into reflections on identity, power and representation.

In the case of Razor Head (1983), my brother had provided two rolls of film, asking me to record a private, erotic, shaving ritual which would last two days. My brother had shaved many men, and taken polaroids of them and he later produced his own S/M tapes for an underground market, but this was the first time we worked together. For my film, I used an effect produced by lighting the colour images with strong shadowing and sometimes fading or moving the light. This comprised the A roll and was combined with a high-contrast print of the same images on the B roll. Printed together, these two rolls show the colour image etched into or evaporating into the white light of the screen. Although I had originally used the effect to approximate the use of blank paper as part of the composition in drawing, by this time I had come to think of it as expressing the transient and spirit-manifesting aspect of material form.

October 5, 1999

Dear Mike

Hoped I would hear from you but then, I said I would call if you didn’t, so I probably will. You sounded a little tired and said you had been ‘up and down’, so I worry that you’ve had fluctuating health. You had written about starting pentamadine treatments and I remember Ken (who had them from early on after his diagnosis) told me that the infusion was unpleasant and often followed by nausea. He did say there was less of a reaction after the first month. My own nausea-producing medicine (sinemet) has been altered to a time-release prescription which is less irritating because not as much enters my system at one time. However, it is not always 100% effective until the next dose.

I’m less in touch with it at present but I remember that in connection with the light I had that near-death experience. You know, the one of going into the light and presences being there on the way. All sound and light were there as I drifted into it. Fragments of voices and sounds and people were present, and if I let go and passed into it, the light and sound would gather into a single sound like a heavenly choir. I felt some apprehension because entering fully into it seemed like dying or leaving the world forever. Then just at the last, concern for someone I knew pulled me back and I wondered if it were possible to go into the light and still be in the world.

It began like a dim star in the very center of the darkness. I had seen it many times while meditating. Sometimes it was blue or red or outlined by halos of changing colour, and sometimes it took forms which I came to feel were projections of my mind. When I began drifting fully into it the forms would pass away. It seemed like the sounds and voices created there were the result of the mind’s attachment to worldly things. This primal light and sound felt like home; it was the place my personality drew from to create experience. Some would say that this feeling is the last stimulation of the phosphenes (that are credited with stimulating dreams) as the brain shuts down in death and the ringing sound is a similar last vestige of hearing when outside stimuli are shutting off. I don’t know.

I also talked to my brother about this when I arrived at the hospital the day he died. He was unconscious and in intensive care on a respirator. The hospital staff said he had reached the point where they suspended the rules about only one person at a time visiting and they encouraged us to talk to him because they said patients seemed to hear although they might not respond and that voices of loved ones sometimes brought them back when nothing could be done medically. I told him many things but then began to remind him of our talks about the light. I asked him if he could see the light and told him he could go into it. I told him he could swim back to the shore where I was with Howard and Andy and Andy’s friend Peter (who came to show Ken his new green-dyed mohawk haircut). I told him I wanted to show him some old photographs from when we were children but I told him that if he felt too tired to swim back he could let himself drift into the light. I stroked his arm while I spoke. His pulse raised once while I was stroking his arm. But later I was told that he had been administered a stimulant to start his pulse up again and that when it only perked momentarily the doctors knew he was probably going to slip away.

Everything in this world is constantly changing. Eventually everything is gone or not what it was. Our attachment to it causes pain and joy, satisfaction and frustration. The light and the sound have a feeling of eternity but they may just be the dot on the TV screen when it’s turned off, fading away. Practicing at non-attachment is a preparation to deal with the gradual loss of everything. I write this as one who cried and wailed with grief at the death of my cat Spider. I am writing these thoughts because they relate to that moment in my kitchen when we speak, and what happens to us. Hope to talk with you soon and that you’re feeling a bit better. All my love, Tom

*(From an interview with Tom Chomont in A Critical Cinema by Scott MacDonald)

(Originally published in Landscape with Shipwreck: The films of Philip Hoffman, ed. Hoolboom and Sandlos, 2000)

Tom Chomont interview by Scott MacDonald (1980)

Tom Chomont by Scott MacDonald

Tom Chomont has been making short, intensely personal, “poetic” films since the early 1960s. The most interesting of them are finely crafted indices of an ongoing process of psychospiritual self-examination. Working with largely diaristic footage – of himself, his friends and lovers, his environments – Chomont fashions dense, subtle, often exquisite emblems of particular states of mind. In general, his work owes a great deal to the tradition of visionary film as described by P. Adams Sitney, particularly to Gregory Markopoulos, but his interest in commercial film, especially the horror genre, is frequently evident: Night Blossoms (1965), for example, centers on a vampire and The Cat Lady (1969) “borrows” a bit of footage from The Creature From the Black Lagoon and combines it with homemade footage into a minimal evocation of the genre.

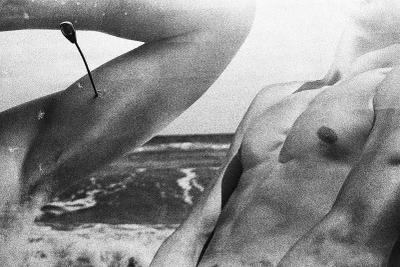

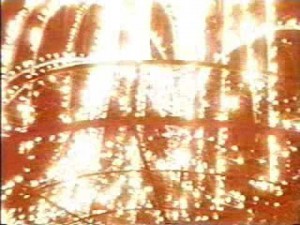

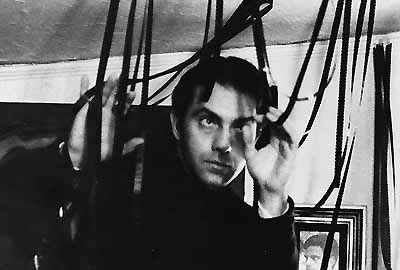

Some Chomont films reveal intense psychic struggles, especially those films he made during the 1960s, when he was coming to grips with his desire to have male lovers. In Phases of the Moon (1968), for example, Chomont uses techniques that are a motif of his work – mirror printing and the combination of positive and negative footage and of colour and black and white, often in superimposition – to image paranoia, self-involvement, isolation and loneliness. Though Chomont’s films are not plotted in any conventional sense, they do develop characters. In Phases of the Moon we often see the protagonist looking through the peephole in his front door; at times this image is mirror printed so that even the protagonist’s attempt to look out reveals his self-involvement and his troubled, schizoid state. In the visually stunning Oblivion (1969), Chomont uses similar techniques to capture a troubled erotic relationship. A lover lies naked on a bed, deeply asleep, while the filmmaker gazes at his naked body and filmically fantasizes about it. The orgasmic nature of these fantasies is evident both in Chomont’s choice of detail (a fountain of lights, for example, is sometimes juxtaposed with the sleeping lover) and, as J.J. Murphy (1979) has suggested, in the overall rhythm of the short film, Oblivion is so densely suggestive – so many levels of implication operate simultaneously in dense bursts of tiny shots and frame clusters – that the film almost defies literary analysis.

In other instances, Chomont images blissful psychic states. In A Persian Rug (1969), for instance, he uses the complex, spiritually suggestive design of a Persian carpet (or a carpet reminiscent of traditional Persian carpets) as a metaphor for the film, which weaves bits of imagery of a hotel room or an apartment, of the surrounding environment, and of a lover – we see only a foot or a leg –into a filmic “magic carpet” that communicates a romantic, mysterious erotic attachment. As is usual in Chomont’s films, formal elements are used to dramatize aspects of the particular psychic state being imaged. In A Persian Rug the film frame sometimes seems to function as a rug-like rectangle into or onto which the lover steps. In Aria (1971) Chomont images an ecstatic state of mind achieved in an Alpine setting. The title suggests the musical structure of the editing and “air,” as in mountain air. Love Objects (1971) reveals the erotic interaction among a group of friends and provides a remarkably open statement about the synthetic nature of such distinctions as “homosexual” and “heterosexual.” After what I assume is an invocation to Venus, we see the lovers together – first two men, then a man and a woman. As he films, Chomont is in so close that he is part of the lovemaking. At times, in fact, his proximity to the bodies keeps us from being sure whether we are seeing a man or a woman: clearly, for Chomont, the intimacy is the issue: the particulars of one’s gender are irrelevant. This idea is emphasized by Chomont’s layering of positive and negative, colour and black and white: the layers of imagery seem as intricately interlocked as the lovers.

In one sense, filmmaking is almost always a pretentious activity. Industry films attempt to address almost everyone, to capture the mood of an entire nation, to mythify a complex culture; the critical cinema often presumes to offer a critique of this immense commercial enterprise. For Chomont, however, filmmaking is above all an unpretentious act, an attempt by a humble individual to see himself clearly. As intricate and inventive as they are, Chomont’s films always have a homemade, handcrafted feel. Chomont has traveled widely; he has lived for substantial periods in Germany and in Holland. But he carries his equipment with him and records and edits (sometimes on a simple homemade editing rig he can carry in a suitcase) wherever he is. Even when he began to explore new processes and new formal issues during the early to mid-1970s, the resulting films did not become academic exercises but remained close to the particulars of his life. When he made Lijn II (1972), abda (1974) and Rebirth (1974) in Holland, he was exploring the optical printer and the development process: he printed the films by hand, using buckets and a homemade darkroom. Lijn II is a tiny portrait of a friend made on a contact printer from scraps of a film that was lost. Rebirth reworks the same brief passage of a man in a bath over and over into an image of a continuous rebirth. In Space Time Studies (1977), his longest film to date (twenty minutes), Chomont provides an inventive exploration of reverse: we cannot tell when the characters, friends he was staying with in Amsterdam, were filmed in reverse (or so that when the imagery was developed, their actions would be seen in reverse) and when Chomont directed them to pretend to be moving backwards. As highly formal as Space Time Studies is, however, it remains a personal film, a portrait of Chomont’s relationship with his two friends and of the environment in which they lived.

Nearly always the issue of becoming spiritually centered is crucial in Chomont’s films. In some cases, it is the primary focus. In . (1974), for example, viewers are trained to search out images of centering, some of which are immediately obvious (circular shapes in the centre of the frame); others become apparent as soon as one is aware of the pattern the more obviously circular images create. In fact, Chomont’s consistent use of mirror printing (I know of no filmmaker who uses the device as often) is probably a function of this concern with centering: mirror printing automatically creates symmetrical imagery in which the center of the frame becomes particularly dynamic. Like Jordan Belson’s spiritual animations, Chomont’s films are often reminiscent of mandalas. Unlike Belson, however, Chomont does not see the spiritual as something that develops apart from everyday life. In Chomont’s films, the medium of film is a means for bridging the gap between the mundane and the mystical: the strip of celluloid, the image on the screen, become a location where the spiritual and the material meet. In Minor Revisions (1979) this relationship is dramatized by the image of an onion being peeled: on a mundane level, the peeling of the onion is a simple act, a diary reflection of the ongoing process of daily cooking (it is also sexually suggestive: the relationship of Chomont and his lover involves their getting together to “peel off” their everyday skins – clothes, uniforms). But Chomont’s decision to concentrate on the onion and to reveal it in double, then triple, exposure, endows the onion with a deeper meaning: it becomes a metaphor for the film itself and for the peeling away of the surface levels of personality to concentrate on spiritual levels. For Chomont, making films has become a medium for enabling the material and the spiritual worlds to discover each other.

I spoke with Chomont on three occasions during January, February and March of 1980. Our original interview was published in Afterimage in June, 1981.

MacDonald: Tell me something about your background, especially as it relates to film.

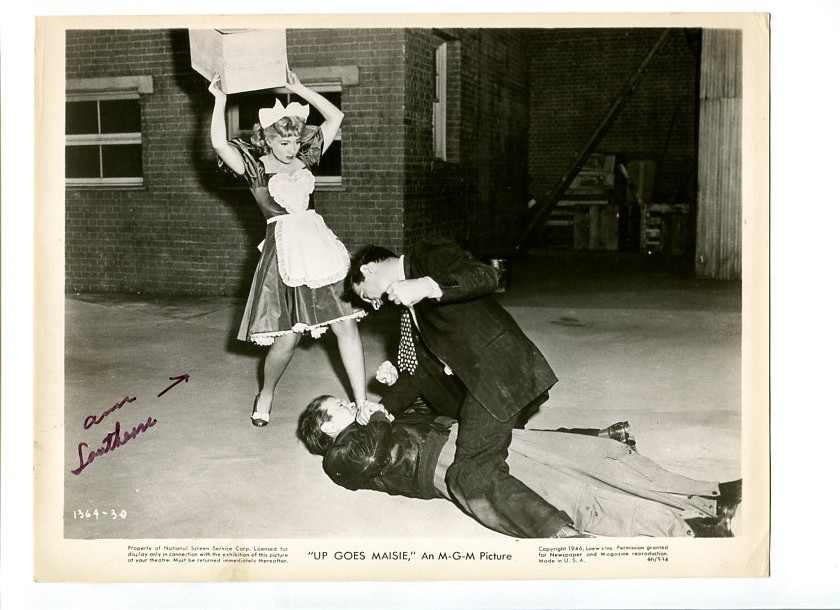

Chomont: The first film I remember was a Castle Film newsreel of Nazi soldiers that my mother and father projected. Later they bought two cartoons by Ub Iwerks – Jack Frost and Puss in Boots – for my brother and me. When I was four, I was out with my father, and he took my into a cinema in the town where we lived. I remember I could not distinguish the beginning of the film; I couldn’t separate the previews from the feature. It was all one thing in my mind, like a reverie, and it took me a while to focus on the screen. I remember just being aware that there were lots of people in the dark room and slowly I felt all of their attention go toward the screen, and so my attention drifted to the screen, too. I remember during the previews the letters coming towards you very vividly. I couldn’t read, of course. It looked like some kind of stylized lightning, and this voice like a crack of thunder coming on the soundtrack. Later I found out the film was an Ann Sothern comedy called Up Goes Maisie.

My parents had tried to buy a silent projector and got a used one that was broken. My grandfather installed a crank handle, and I remember cranking a Felix the Cat cartoon and watching the whole illusion of the frames – I think I was about three years old – how you could make it into still pictures or go faster and make movement.

When I was about four, I tried to draw a film on a sheet of paper, and when I got to the end of the paper, I drew a spiral that got smaller and smaller. I had the idea it could be projected, and when I went to cut it out I saw that it was too big at the beginning and didn’t work at the end.

MacDonald: Did you start making films as a kid?

Chomont: No, I wanted to, and I also wanted to take photographs. My brother did, too. My parents would fool us by giving us the cameras with no film in them – they were afraid we would waste film – and the film would come back and we would look for what we’d taken and it was never there. But I always dreamed of making films. When I was about ten my brother and I got the idea of filming short stories with puppets. We would plan and write little scenarios. We never did them, but the idea was there.

I was always fascinated by dissolves and fades, all those effects that you didn’t have in life but that had an expressiveness, that were true in a psychological sense or in a memory sense; events did sort of meld together in the memory and here it was literalized in film. Later I remember liking Jack Clayton’s Room at the Top because of the dissolves.

One of my sisters gave me an 8mm camera the first year I was in college, an old Brownie with part of the viewfinder broken off, so I had to learn to estimate where the frame really was. I used black and white film, high-contrast newsreel stock. I had to order it because the camera stores didn’t carry it. I wanted to be able to walk in and out of buildings filming. I used colour too, but only if I knew I was going to be outside in sunlight. Later, when I couldn’t get the black and white, I began shooting colour inside. I think I’d read Film Culture already (this is when I was about 19), and Brakhage talked about how you could heat film and change the colour balance. Even though you lost what the companies considered the real colours, you could get expressive colours.

I thought of what I filmed as a diary. I had held the camera, and I prided myself on being able to shoot without looking through the viewfinder. I began in 1961 and continued doing that through 1963. Then I took the family’s Bell and Howell camera and started buying 16mm magazines. I felt I had to do something more planned, though the diary continued. It may have come out of the fact that when we moved from Illinois to Florida, I felt a loss and afterwards always felt the desire to capture things. I already felt that the most paradisiacal part of my life had been lost: that first house where I first saw films, where I enjoyed everything like a little tyrant who had free time (my mother was confined to bed for some time; my father worked; my grandfather was very indulgent and mischievous), the rabbits, the pheasants, the woods and snow. Suddenly we were in a flat, warm, humid, overly fertile area that was somehow very deathly – everything burning up from the sun. In the diaries I was just making stabs at trying to retrieve things. Even when I made a planned film, I was trying to save pieces of experience.

MacDonald: Did you study filmmaking?

Chomont: Yes, eventually, between 1964 and 1965 at Boston University. Alvin Fiering was the production teacher at the time. Gerald Knox, Tony Hodginson and Robert Steele were there. The production course was oriented towards social documentary.

MacDonald: Did you make social documentaries there?

Chomont: Well, I tried.

MacDonald: There’s still an element of that in your work.

Chomont: Oh, yes. I wasn’t opposed to it. I just felt constrained. Finally I dropped out. The only reason I could see to finish was to teach film, and at that time there weren’t many places teaching film. Today I’m sorry I didn’t do it.

MacDonald: Did you stay in Boston?

Chomont: Yes, for about half a year after I stopped classes. I was working in a cinema as a ticket taker, and I was programming a film series in Cambridge. At the time nobody in the area was regularly showing what was being called Underground, or the New American, Cinema. I thought maybe I could organize something, so through the cinema and the projectionist there, I managed to set up a benefit showing of Gregory Markopolous’s Twice a Man at the Odd Fellows Hall in Cambridge – which made a very nice poster! I started showing films once a month, the once every two weeks. I had to hire police to be in the hall because at that time it was open to the public.

MacDonald: Who did you show?

Chomont: Oh, Stan Brakhage came in person. He did a show over two hours long including the 8mm Songs. This would have been late 1965. We showed Markopolous (who also came to Boston and filmed there), Robert Nelson, Bill Vehr’s Avocada and, later, Brothel, which turned out to be the film that got me shut down, but that was after about a year.

I had the premiere showing of Andy Meyer’s Match Girl and An Early Clue to the New Direction (Meyer layer made films for Roger Corman), and George Kuchar came up with some of the 8mm films, and I showed a mixed program in 16mm of George and Mike Kuchar. And there was a Maya Deren program, a Bruce Baillie program, a Kirsanov program (Kirsanov was a Russian director who worked in Paris), La Chute de la Maison Usher by Epstein… the standard experimental film society program at the time.

The police tried to intimidate me. They claimed I was showing dirty films and that the hall wasn’t licensed to show films. I remember having a 104 degree fever and getting furious and shouting at the chief of police of Cambridge over the phone (I was very naïve at the time, very idealistic), “And you’re not going to get away with this!” I just kept calling everyone in the Buildings Department until I determined that the hall was licensed for films. Then not only did they decide it was legal, they decided to send two chaperones – that was for the Jack Smith Normal Love rushes. The chief showed up and watched the program, and I remember some people laughing because he apparently didn’t see it as at all bizarre. Jack had not included any nudity in what we showed, but I hadn’t known that. Now it seems supremely stupid to have taken those risks, especially fighting with the police, but nothing happened until one policeman reported me for showing Brothel, and the chief phoned me three days before the next showing and told me they were quarantining the whole hall. They nailed the door shut, put a public notice on it. I had no way to notify people – the posters and the mailing had gone out to the members – so I mimeographed maps of how to get to MIT (Fred Camper agreed to let us show there.) Gregory Markopolous was coming with the original rolls of his first portrait film, Galaxie, and I didn’t want to cancel, so I just went down with maps, and the chief was standing there when I was handing them out. He had his whole regalia on. He said, “Don’t ever try to show films here again because I’ll close them.” They tapped my phone for over six weeks. Friends would phone up and say, “The body’s in the trunk” and things like that, but I was very nervous.

With the Swetsof Gallery we did a showing of Match Girl and Jean Genet’s Un Chant D’Amour. We had two showings because it was a small gallery, and sure enough, at the second showing, two plainclothesmen tried to get in the door. Mr. Swetsof was very clever; he just stepped outside the door and slammed it. (He had locked the door on the inside so when he shut it he couldn’t even get in himself.) It was very exciting. I’m sure the bravado was inspired by reading about Jonas Mekas and Flaming Creatures. (Early in January 1964, Mekas – with Barbara Rubin and P. Adams Sitney – stormed the projection booth at the Third International Experimental Film Exposition in Belgium in order to show Jack Smith’s film. In March 1964, Mekas was arrested in New York for showing it.)

MacDonald: Were you doing this by yourself?

Chomont: Yes, I had some backing from the manager of the cinema where I worked for a while, but he pulled out when he saw that it wouldn’t be a big money thing. I did the series for about eleven months. Then I moved to New York.

MacDonald: When did you first start showing your own films?

Chomont: I never programmed my films in the series. The first time I showed publicly was in 1966 at an open screening in New York at the Cinematheque on 41st Street in the old Wurlitzer Building. (Later I was the acting manager there.) I showed Night Blossoms; it was demolished (laughter) – a horrible experience. In 1968 Jonas showed an earlier film, Flames, and he showed some others later. Vicki Peterson saw some films at Bob Cowan’s house in 1969, and she programmed Ophelia (1969) and The Cat Lady on a program at the Rockefeller Institute. Really, public showing started when I went to Europe.

MacDonald: How long were you in New York?

Chomont: The first time I was here from June of 1966 until August of 1969. In September I went to Europe.

MacDonald: Did you manage the Cinematheque all the time?

Chomont: No, no. I managed it from about July of 1966 until about March of 1967. I wasn’t happy acting as manager of the Cinematheque; people were always relating to me as the manager and not as a filmmaker. Personal relations had gone very badly. Everything seemed sort of hopeless. I tried to make some films, and they were very depressive, very masochistic, I suppose. I found them too embarrassing and never finished them – they got thrown away. Now I’d like to go back, because it was very revealing material that I just happened to have access to due to the state of mind I was in. Then I got food poisoning: that seemed to snap me out of it. I realized I did want to live, and I began the longest film I’d done up to that time, Morpheus in Hell (1967), which turned out to be about sixteen minutes.

I was working in an office then, typing. I began to feel like a machine, and to have these very mechanical rhythms in my sleep that were like dreams, and then eventually even when I was awake I would sometimes see landscapes and faces in front of me when I closed my eyes. We would be talked into working until two or three in the morning one night a week, when the deadline came due. Once, I came home and I just stood in front of the mirror and talked to myself, and I said thing I didn’t even know. The odd things was that I experienced both talking and listening to the face in the mirror. Sometimes I would look at the face and see the lips moving and hear the words coming like someone else talking, as though that face were telling me something That was part of the beginning of Phases of the Moon, which was shot in the same mirror, and the whole idea of the split in the personality that’s in that film. Then I began to realize two isn’t enough; it’s really millions, because all the faces are us; we have to split into more than two – we have to keep splitting until we know all of them. We don’t have to, but I felt that way then. I was not religious; I did not really believe in God; I did not really understand metaphysical statements; I had trouble with a lot of philosophical writing. It was a real experience: after splitting in two, it was clear that identity was not as fixed as I had been taught. As I see it today, Morpheus is a sort of ego death and rebirth.

I was terrified of going crazy, of being crazy, at the time. I mean all these things half fascinated me and half terrified me because I felt very alone and isolated. When I was making Morpheus I used Tarot cards. I’d had a dream about them, where I was in a hotel that seemed to be in Europe (I had never been in Europe at that time) and there was a cigarette stand where I bought these old cards – somehow I understood they were Tarot cards – and the design on the back of the cards included the word “clairvoyant.” I suddenly realized it simply means “seeing clearly.” Then I had this urge to get the cards and that became one of the bases of seeing Morpheus. Since high school I had approached dreams from a Freudian point of view. I had been determined to see them in a rationalistic, analytical way. I began to let myself just experience the seemingly irrational connections that took place during sleep and in other experiences.

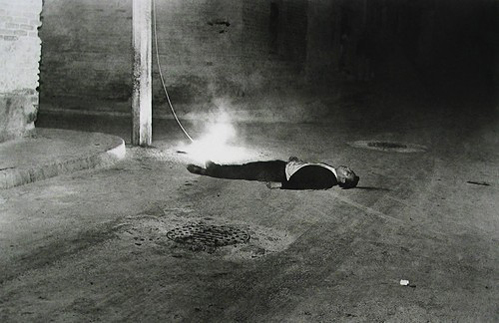

I had a dream where I was in Herald Square (I didn’t realize it was Herald Square then), and as I was coming across 34th Street, the sort of steam that comes out of manhole covers seemed to be filling the streets, and I was being engulfed in it. At first I enjoyed it as an unusual experience; then I began to feel that somehow this smoke was going to put me to sleep or suffocate me, and that, in fact, the whole city was either dead or asleep from the smoke, and maybe it was some kind of invasion. I began to run, when I realized it was drifting with the speed of the wind, and I couldn’t outrun it, and I was becoming engulfed. I had this panic (by that time I was panicky enough that I was waking up), that maybe I would die in this dream somehow, and I wanted to wake up, but when I managed to open my eyes, I wasn’t in my bed – I was up over the bed looking down. It was almost as though the room were sideways, as though the up and down had changed, and I felt like I wasn’t in my body any more. I t seemed like I could almost see that the sheets went down and there was my body, and I was somehow looking down, and I was terrified. I thought maybe I had died or had somehow become disconnected, and yet that whole idea of myself apart from my body was alien to my concept of reality at that time, and I cried, “Help,” and in making the effort a melding took place, and I was back on the bed. I’d never heard of out-of-body experiences. I just thought it seemed insane, and I was afraid of being taken over by irrational forces. That was in the time of Phases of the Moon. I had shot it but hadn’t edited it.

MacDonald: Phases of the Moon puzzled me when I was looking at it. What you’re saying makes it clearer. There’s a person who seems to be waiting for somebody, or he’s closing himself off from somebody. I couldn’t tell which.

Chomont: Neither could I! That’s exactly right.

MacDonald: I thought he was either waiting for a lover or getting ready to commit suicide.

Chomont: I didn’t even think that much was in the film, but that’s exactly the state I was in. On the one hand, I had an urge toward self-destruction, and on the other I wanted to get in touch with people. I’d lived almost a year near Central Park West and never realized it was a gay cruising area, and then one night I was walking and suddenly noticed men looking at me. My mouth just dropped open. I was aroused! One man approached me and I must have looked petrified. I immediately felt he was a hustler. He was living with his mother. I was afraid to bring him to my room, but I finally relented. Then he used to come over sometimes, and he began bringing other people. It turned out he took cough medicine (for codeine) as well as seconal; sometimes it was like he was dead. That got into Oblivion later.

I had the typical New York door with the chain and all the locks and the peephole, and at night I would hear someone in front of my door. It was like a little broom noise and I began to have this paranoid fear that someone was sweeping some poisonous powder under my door. I would jump up and try to see what it was, and one night I saw this older man in an undershirt and old-fashioned undershorts with flowers. Apparently he had been sweeping his rug in front of my door – I guess he didn’t want the dust by his – but all these things made me very paranoid. The superintendent was very nosey, too. I had to smuggle people in, which enforced the isolation. All that got into Phases of the Moon.

The other thing it’s about is the mechanical actions we do unconsciously. I had become very aware of them because of the typing I was doing. I had begun to feel like an extension of the machine at the office, rather than a person. Then I became aware of the little things that I did mechanically, on a robot level, in my room; my fear – and my longing, at the time – produced mechanical patterns of looking out the peephole. The whole film had to do in part with irrational things: mechanical movements in a way are not rational. They may have been in the beginning, but then they take over and are simply performed – out of context as easily as in context.

I painted when I was in high school. I never found myself in painting (though I got my bachelor’s degree in it), and I had to go through the same process with film. Many filmmakers make their first film, and already it’s distinctive. I admire that, but it wasn’t me. I staggered around for a long time. I think it was the last half of Morpheus where I felt this is beginning to be me, and with Phases of the Moon I thought yes, this is mine.

MacDonald: The man looking through the peephole in Phases of the Moon suggests, at least to me, your looking through the camera.

Chomont: That early part where he looks through the door and sees himself in the room was a metaphor for me filming him through the camera – the peephole. Then he’s looking out the window, and he’s like the spectator looking into the frame. You don’t see out; you always see him again and the room, like a reflection, which I felt was reflective of me. Then there’s the point where it’s like he’s kissing himself. His two faces blend, and he’s looking through the keyhole both ways; it’s like the viewer and the viewed come together.

I couldn’t have dealt with all of that in words at the time; if I could, the force of the film would have been gone. It’s that buildup of having something you can’t quite say with words, or you don’t understand in terms of words, which makes filmmaking necessary. That’s the whole problem with writing about films, too. You cannot duplicate all aspects of the visual expression.

From the little I’ve read of semiotics, it seems an attempt to codify visual expressions into symbols comparable to language. I’m always afraid it’s not really encompassing the ambiguity of imagery. It seems to me we already have language; we already have a number of codified, highly symbolized forms of expression. Art has always been to me an ambiguous and polymorphous form of expression that resonates and coruscates and transforms. Even when you try to codify, there are always other aspects, other levels, that come into any complex form of expression. I think some structural-minimal films play with that. You narrow down, and then here comes another level; just by narrowing down you pinpoint it more. I’m always afraid words will falsify the image, but, yes, I can say now in words what we said about Phases of the Moon, that the window and the peephole are metaphors. To some extent my films were then, and probably still are, therapeutic ways of seeing and dealing with things I couldn’t come to grips with in other ways.

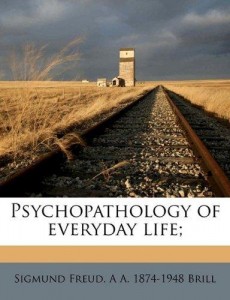

MacDonald: Why the subtitle The Parapsychology of Everyday Life?

Chomont: It’s a pun on Freud. In high school I read The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, which is the rationalist approach. He’s calling all these irrational, illogical, basically emotional and primal connections that occur as a subtext to the waking, conscious, well-behaved, civilized world – he’s calling them “psychopathology.” He’s making them pathological. In that period I was experiencing these from the other side, the non-rational side. “Parapsychology” isn’t negative; really it’s not a subtext – it may be the main text, and the “civilized” may be the captioned version of our lives.

MacDonald: Did you interest in superimposition and using positive and negative come out of your interest in multiple selves?

Chomont: Partly. The way it was used there it did, but the idea originally came to me when I was living in Boston and did Night Blossoms. When I was painting, I had the decision of how much of the surface to fill in – you can leave part of it blank. In film it seemed like you really are filling everything in; it’s hard not to. I thought the way to avoid that would be to use positive and negative, turn the shadows into flat blank screen and make it so that the colours would be like drawing. I wanted to do that in Night Blossoms, but the expense of making negative to combine with the positive just seemed to much at the time.

MacDonald: As you say that, I think of Ophelia.

Chomont: Oh yes. That’s the most extreme of the early films; the screen’s practically all white; the colours are very slight and give a daguerreotype look. You see a lot of the grain. It was a very dark image, which I made into a negative and then used the negative to blank out the screen and allow traces of the image to come through. I wanted to move the light to give it a watery look, but I don’t think that came off so well.

It was filmed in a bathtub. It came from the Millais painting of Ophelia for which, I had read, he had asked the model to lie in a tub of water heated by candles. Somehow looking at the picture you feel the posedness of the subject in the water, and I wanted to do something stylized like that and use the film emulsion as the water – the figure (Carla Liss) coming in and out of the emulsion. It’s like washing the emulsion off the film, then sketching in.

MacDonald: I’ve never seen anybody else do that.

Chomont: Aspects of it have been done. For example, shortly after I made Oblivion, which I thought was the most exciting thing I had done using that method, I saw T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G by Paul Sharits. He intercuts frames of pure colour and of black-and-white negative and positive. The effect is similar. Solarization and some video effects resemble it, too.

MacDonald: You use the sound of the sprocket holes, which gives a one-second pulse. Is that automatic, or did you do something to get that pulse?

Chomont: It’s just the sprockets. The regular pattern of the edge numbers and letters probably causes a pulse. I didn’t originally think to make Ophelia a sound film, but somehow I thought of Ophelia and The Cat Lady as one film in two parts. When I decided to show them together, I realized sprockets would be very nice because they give a somewhat mechanical feeling that goes with that textural feeling of the emulsion.

MacDonald: In The Cat Lady I presume that you combined a shot you took of somebody you knew and some found footage from a sci-fi film.

Chomont: That’s about it, except for one random image taken from the room where I filmed Carla Liss. Originally I filmed more, it was going to be an homage to horror films. I’ve always had a predilection for horror films, especially the more fantastic and spooky ones. Carla always seemed to me to be a rather glamorous figure. She’d been in a number of films around that time – Andy Meyer’s and George Kuchar’s. Her work with film and mixed media had been exhibited in New York and London. She was also the director of the London Co-op at one point. We had been in film school together in Boston, and I asked if I could film her for this. I filmed a lot of things in her apartment, and then something very tragic happened to her. I was in a very withdrawn, tentative state myself so I couldn’t deal with it; as a result, I couldn’t deal with the footage either. That was in 1967. Then in 1969, it began to grow back to me, and I combined it with this stock footage I took from a 10-minute edition of The Creature From the Black Lagoon (It’s from the creation of the world sequence) I’d gotten as a birthday present. I turned it upside down, and I turned the sound upside down – I reversed it so that it’s an implosion into Carla. That shot is repeated six times; a shot of Carla’s hand, four times; a shot of Carla’s head turning, twice; and the shot with the lamp is seen once. Those are the only shots in the film. The repetitions are not identical.

It seemed like a very slight idea, and then the first time I showed it, everybody liked it. I felt like a cheat. It was so easy to do, and the most spectacular effect is taken out of another film!

MacDonald: I think it’s the way the two things works together. There’s a place where her face appears in the clouds. The material implodes directly into her heart.

Chomont: I knew how it all was going to go before I did it. I synchronized it by taping one end of each strip to the door, stretching it (with a coat hanger on a lamp out over the room, and lining it up frame by frame. But after it was all edited and printed, I had to admit that I didn’t entirely foresee its effect. I was thrilled.

MacDonald: After the lamp shot, there’s blue leader with blue flashes, but the soundtrack is still on.

Chomont: Right, I just decided to leave that on; even after the film ends, you have the feeling it could start up again.

MacDonald: In a number of your films, including The Cat Lady, there’s a surprise at the very end, where the film seems to break from what’s gone before.

Chomont: Jonas (Mekas) once wrote some very complimentary things about my short films, but he said my longer films tend to break down and fall apart. (Reading Jonas’s “Movie Journal” column in the Voice from 1960 on, by the way, was an enormous source of inspiration and encouragement to me.) In a sense, Jonas was right, but what he noticed was something I’ve meant to do, starting with Morpheus. The whole structure begins to unravel, as if to say the experience doesn’t really end, this is just where I’m ending the film.

MacDonald: After Ophelia and The Cat Lady, and with the exception of Re:Incarnation (1973), you don’t deal any more with sound.

Chomont: No. I keep thinking to, but it’s a whole thing in itself and requires so much equipment – to do sync sound anyway. I’m not opposed to sound, though there are films (like Oblivion) that I’ve never, ever thought should have sound.

MacDonald: Oblivion and Phases of the Moon are in the tradition of trance film and psychodrama. Oblivion reminds me of Kenneth Anger’s Fireworks. How much of that tradition had you seen when you made those films?

Chomont: Oblivion was shown with Fireworks recently. The first experimental films I saw were mostly trance films or reactions to trance films, but by Oblivion I wasn’t really directly concerned with that. Oblivion was a diary to a large extent – a diary and a portrait and a confession. The first films, like Anthony (1966) and Night Blossoms (1965), are rather like trance films; that’s part of the reason I didn’t think of them as my own.

MacDonald: Did you shoot Oblivion over a long period of time?

Chomont: No. It was shot on two separate evenings, but had elements of many of our visits. We would sit and talk, he would smoke, and at some point one or both of us would feel aroused. Usually he would take off his shoes when he wanted to have sex; that’s in the film where his hand untying his shoe is blended with a pan of his body on the bed.

MacDonald: One of the things I noticed about Oblivion and several other films is a tendency to use synecdoche; a detail of something that’s happening takes on multiple dimensions. It’s interesting because what tends to be diaristic for you, with that condensation, has a different effect on the viewer.

Chomont: Yes, I felt this material was highly personal, I was conscious from the beginning that there had to be a formal side. The experiences themselves had broader meanings of identity and role-playing and the face as a mask. I wanted to give the film the feeling of being between dreaming and awake. All the imagery had personal meanings, but of course I didn’t use everything I filmed, and I had symbolic meanings in mind. The apple was symbolic: besides having the Biblical reference that J.J. pointed out (Murphy, 1979), it had an erotic look – the redness, the dimple, the stem, all of that.

MacDonald: The fountain of lights seems suggestive, too.

Chomont: That’s from a store on Fifth Avenue. At Christmas they always used to have these canopies made of strings of lights and a light fountain over the main doorway. I filmed that and thought of it as the nervous system and the circulatory system.

MacDonald: It suggested ejaculation to me.

Chomont: I masturbated a lot in that period, and I became very aware of the connection between ejaculation rhythm and pulse. I thought of it as all those things; I didn’t know what it would mean to someone else. I was trying to mix carnal and metaphysical elements, though it wasn’t clearly formulated in my mind.

There’s always a tension for me between the fact of seeing someone from the outside – as a body, an object – and seeing the identity dissolution that usually takes place during sleep. If it happens when we’re awake, it’s disturbing; we want to avoid it. I was trying to deal with that. Sex fantasies tend to objectify other people’s bodies and sometimes their personalities, too, and I suppose it’s evil in a sense because it can lead to the manipulation of other people. That was a tendency in that relationship because he took so much of those drugs. At that time, I think he had trouble accepting his sexuality. He said it was easier to accept performing sexual acts for money, but the fact of the matter was that he would sometimes take the money he earned and go buy another prostitute to have sex with him as he wanted it. Twice he asked me to pay him to have sex and I thought, “This is a very bad precedent and besides I can’t afford it.” Well, I resisted it, but I was aware that it appealed to me to just say, “OK, what will you do for this much?” After many years of trying to follow what I was taught – not to do certain things sexually – I had a lot of very intense fantasies. During this time I began to act out my fantasies, and, in doing so, the experience became more important than the fantasy.

When something sexual seems impossible or unthinkable, fantasies are horribly exciting, horribly intense; yet I think that’s the beginning of seeing other people as part of your own concept of reality, and that makes it hard to break through to other people as they really are. I guess I can think of it like a time warp, where other people are us but in another place and time; in a sense Oblivion is a view from the evil side, the side of desiring to manipulate another person’s body and person. (Of course, that’s involved in any portrait of likeness.) I thought of it at the time as simply accepting the fact of being turned on by other guys, confessing that, and trying to show something of it. It brings up the whole question of sexual identity, of role-playing. At times his body is like an object, as the apple is an object containing life, so this whole border between objects and definitions of things comes in too.

MacDonald: A technical question: near the beginning the image breaks down into three levels…

Chomont: It’s just an A and a B roll; the A roll has a red filter; the B roll has a green filter, and where they overlap you get yellow. The reason I did that was for the 3-D effect. Actually I just filmed everything twice from a slightly different angle; if you wear red-and-green glasses, momentary stereoscopic effects slide in and out.

MacDonald: You seem very interested in 3-D as a process. There’s your holograph, the 3-D film Mouse In Your Face, and this.

Chomont: Mouse In Your Face was sort of a joke. The title wasn’t mine. Joe Glin had some ice and gerbils here. He knew I was annoyed about the mice because they smell and they squeak a lot. I was having a show at Millennium in a month and was trying to finish new films. He had shot a film he hadn’t finished, and I said, “If you want to finish your film, I could show that too,” and he said, “No, I’d rather make a new one called Mouse In Your Face.” I said that would be a great 3-D film. One evening when I was alone here, I filmed the mice, swaying to get the two views. The polarized light of the Polaroid system is best, though, for 3-D.

Something I was thinking about at the time of Oblivion is the relationship of the right and left hemispheres of the brain to the right and left eyes. I had forgotten that both right and left eyes connect to both hemispheres; there’s a crossover point and somehow the information exchanges, but seeing stereoscopically does seem to have something to do with the two hemispheres. I understand they say in psychology – in meditation people told me this many times – that the right tends to be the verbal side of the brain and the left tends to be the instinctual, intuitive, irrational, side.

MacDonald: You were talking earlier, in connection with Oblivion, about splitting into various selves. Is the 3-D process used there a metaphor for the idea that if you separate into separate selves and then come back together, you get more perspective, more dimension, than if you’d stayed the way you were?

Chomont: That was how I originally conceived it. As the film came out, it seemed less important than that. I still would like to use 3-D that way. Also, I’d like to get the viewer’s eyes to perform certain movements in the course of seeing the film that would have a soothing and unifying effect, that would be like visual exercises in meditation.

Visual meditation exercises are based on locating a central point in your visual field. I think it’s a point that infants must look at a lot, even before birth. In fact, the first time you see it consciously – from all I’ve read and from my own experience – tends to call up pre-birth memories. It’s there all the time but we just don’t look at it. If you start looking at it again, like with your eyes closed, or even with them open, it can start to radiate light, because you’re concentrating so much energy that the visual field just starts to light up, and you can pull energy from that. I first saw it as the two eyes on someone’s face coming together. I associated that with the two hemispheres and the two sides of the face, and I thought, this is like unification. I associated the centre point with a flame; eventually I saw this point all on its own, eyes open, eyes closed. A lot of people who are brought back from death describe having seen an intense light. That’s what it was like the first time I saw it – a star that got more and more intense and it was like I could go into it and leave everything, but in part of my mind that was like death and I was afraid of it. On the other hand, I felt, well, it’s coming anyway… but I couldn’t accept death, and this seemed like a failing. It seemed like acceptance was the reality, and the rest is striving. In meditation they describe people who do accept that state and “die” and their striving is over; the rest of their life is simply to help other people complete the cycle. I couldn’t do it, but I know it’s there.

Of course, we’re more than two brains; we’re much more, much, much more. It’s like the yin and yang. Many people react to the yin and yang because they think it’s a reinforcement of polarized masculine and feminine characteristics (which some of the literature is), but what it really is, is the idea that everything can be considered as having two aspects, and from that you can keep dividing infinitely until you get down to the molecules, the atoms, below the atoms to the energy. We’re already divided into at least two and we can keep working from there down to our cells if we want to. Somehow film seems to have all that in it, at least metaphorically; you can become conscious down to the movement of the grain. A lot of what was going on in independent films and in reviewing when I began making films seemed to be involved with that kind of awareness.

MacDonald: I’ve assumed that the title of A Persian Rug refers to an analogy between the structure of the film and of Persian rugs.

Chomont: It was an intuitive title, and it really referred to my having just read Indries Shah’s The Sufis. In the house where I was staying when I did the filming, and where part of the filming was done, there was some kind of oriental carpet on the floor. I didn’t know if it was a Turkish rug or a Persian rug, but as a reference to Persian Sufism I called it A Persian Rug. The traditional Persian rug is a religious form that is an homage to Allah. There are very traditional designs, but the rug makes always weaves an imperfection, an asymmetrical or irregular place, to say that only Allah is perfect. I thought of those things with the film, but the title was intuitive.

MacDonald: One of the things that led me to think of the connection is that the first you time you actually see a rug, it fills the frame, and then simultaneously you see a foot protruding onto the rug and into the frame. The rug and the rectangle of the image function the same way. I even thought of film as a magic carpet.

Chomont: That was intended. At one point, the film is so overexposed that the only image you read is the rug and the feet; you don’t really see the floor.

At this point I’d like to say that I never faded in the lab in any film; I do all fades and all changes of exposure myself. None of my films are timed. I want the lab to do what’s called a one light print, preferably along the lines of a workprint, because I want everything the way I photograph it. I avoid laboratory-done things. If I can work on a printer, I’ll play tricks with it, but I want to do it myself.

MacDonald: When you made Oblivion and A Persian Rug, did you construct the films as you were shooting, or did you do random diary recording and then later decide to use that?

Chomont: In those films it’s a combination. Sometimes I head out to get certain images. Sometimes I make images without knowing how they will fit in. Sometimes, in editing, I change my idea. In the beginning it was often a big struggle for me to get over my preconception of how I was going to do the film and accept what I really felt was the best way to do it – especially after film school, where you’re supposed to plan everything.

I started using splicing tapes because I could change what I had planned and cut without losing frames. Also, I liked the whole feel of splicing tape. You put in on and smooth it and trim it; it has a very handcrafted feeling to me. In film school splicing tape was considered unprofessional.

MacDonald: A question relating to the nature of handcrafting films: do you work wherever you are?

Chomont: Yes. When I was traveling I had an old rewind mounted on a board. I did Portret (1971), Love Objects (1972), Research (1972), all those films, on it. It was made in Czechoslovakia and had collapsible rewinds. I carried that in my bag and would just pull it out. If I couldn’t edit in one place I’d carry it to the next. I’d always carry some little 100-foot reels so I could work in short segments. A Pesian Rug was filmed in Orselina and in Locarno. Then I went to Zurich and started editing it there, moving from one pension to another. It’s nice to go into a real workshop and sit down, but, of course, they’re only open so many hours. I’d rather be here and get out the clothes hangers, put up the film, and take down the pieces I want.

MacDonald: In A Persian Rug, and in other films, you use a limited number of images, or kinds of images, and then reiterate them in different contexts. Is there a background for that way of constructing a film?

Chomont: Probably the biggest single influence on my editing is Gregory Markopolous. He doesn’t do variations so much as progressions, at least in the films of his I’m familiar with. I did a transcript of his film Twice a Man, where I actually made note of each shot: the number of frames, the content of the shot, and when it was repeated. It took some months to do and made a very big impression on me. I saw the film as precisely musical, precisely rhythmical, though he told me he didn’t count frames, but did it by feeling.

MacDonald: Life Style (1978) seems to have come out of a time when you were involved in a lifestyle that involved a lot of drugs and hallucination.

Chomont: It was about a couple I lived with in Brugge (Ioanna Salajan and Richard Lamm). They were into macrobiotics and yoga, but I talked to them a lot about hallucinatory experiences. I had been afraid of hallucinations from LSD and mescaline, more from LSD.

The people in Life Style had never taken LSD or mescaline, but they described equally fantastic experiences they had had just through meditation, and I had many of them. The difference was that you could stop it. Ioanna (especially) and I, and Richard and I would look at each other’s faces, and I would see other faces – sometimes animal faces, sometimes fantasy faces. They had explained to me that the whole body tends to have a right/left dichotomy. (Palmists say the left and right hands express the innate and the actual character of the person and the differences between them.) During that time a psychology magazine published photos where they duplicated one side of a face to be both sides, to show that each side actually expressed a different person. That was all very interesting to me because I had done that in Phases of the Moon two years earlier, where the man looks in the mirror and his face is the same face overlapped. I’d been doing a lot of things with the mirror-image type of thing. I filmed Life Style during that period (early 1970), and there is a lot of hallucination, but it’s supposed to be about meditation.

MacDonald: I thought of drugs because there are a number of processes that go on – things being washed, as some sort of glass thing – and I couldn’t identify what those were.

Chomont: Well, she’s washing bean sprouts in a sieve. Also, they were working on a light show with a rock group called The Circle from Ghent, and had developed a process of using colored liquids suspended between two sealed plates of glass made into discs. The glass disc that Ionna has in front of her face is one of these.

MacDonald: Were the light shows connected with the fact that as the film proceeds it gets lighter and lighter, and sometimes completely whites out?

Chomont: When you’re doing visual meditations, you’re supposed to try not to blink. That’s not the objective, but a sign of when you’re getting to a higher concentration is that your eyelids don’t blink. When you don’t blink, your eyes tend to become very sensitive to light: even a room lit by candlelight can become excruciatingly bright. Also, you begin to see more of the spectrum. The film reflects that, though I didn’t consciously set out to do it.

MacDonald: Untitled, the film shot off TV, reminds me a little of (Fernand) Léger and (Walter) Ruttmann.

Chomont: The shooting itself was part of some experimenting with film stock I did when I was staying with Daniel Singlenberg in the early summer of 1975. He had just gotten this used TV, and I thought the test pattern would be a good image to develop. (I was developing film myself.) Also, I saw a connection with stages of consciousness. The test pattern seemed like a mandala. The film goes from a mandala representation to pulses that I would connect with the workings of the body. Then you have illusionistic perception. The most illusion occurs when the frame of the TV disappears and you’re thrust into the picture as the camera is racing down a mountain road. The film begins with a sequence of shots which, except for the middle part, the bicycle race, are repeated in reverse in the latter part of the film. The imagistic shots are turned right side up both times in most cases, but the non-imagistic shots are literally just the reverse of the beginning of the film. The bicycle race occurs only once – right side up in the middle – and even in that section there’s a photograph of a group where a bicyclist who’s being discussed on the TV is indicated by a circle around his face. That, too, struck me as a mandala-type image, occurring in an illusionistic image. So I thought of it as going from levels of internal perception into external perception and then back.

MacDonald: Is that true of Portret, too?

Chomont: Somewhat. I associated it with Mallarmé’s interest in developing certain poems so that they would be completely rounded. I wasn’t interested in symmetry but in a rounded form that could be approached from either end. I suppose I would trace that back to reading about Alain Resnais and Alain Robbe-Grillet wanting to have the reels of Last Year at Marienbad projected in different sequences. They felt there was no beginning or end to that film. That appealed to me. Also it was influenced by Renaissance and Mannerist painting. For instance, I realized that angels at the top of a painting were – if you turned the painting upside down – quite clearly painted from models lying on sofas or rugs. After I’d finished Phases of the Moon, I saw 2001, and what intrigued me in that film (which, on the whole, didn’t impress me much) was that, due to the lack of gravity, you had compositions where there was no strict up or down. I thought of Phases and Portret that way.

MacDonald: You list Portret as black and white, but actually…

Chomont: I guess because I don’t want people to expect colour. Black and white film always has a tint to it. Here you have different mixtures because there are so many different film stocks in the original.

MacDonald: I like the colour.

Chomont: There’s a quality I like, but I’m not sure I would miss it that much if it were printed on black and white stock. Portret was very short, and since I was printing Aria, I thought, well, I can print Portret and Aria together and show them together. I always try to put several short films on one reel; otherwise they’re so short they’re hard to show. So I printed it with Aria, which is full colour and then I thought the colours in Portret were interesting, though I continued to think of it as a black and white film. I also thought of it as sort of a Busby Berkeley dance number made up of Eric DeKuyper’s face.

MacDonald: Aria is dedicated to RB and GM…

Chomont: Robert Beavers and Gregory Markopoulos.

MacDonald: I’m not that knowledgeable about music, but I looked up “aria” and found that it’s an elaborate melody played by a single instrument. Were you consciously punning on the camera as an instrument using, in this instance, the single point of view of the window?

Chomont: Yes. At that time I thought of all my films as having a musical structure. Now I wouldn’t say all, or at least not all parts. The aria seemed particularly apt in connection with Robert and Gregory. I discovered later that “aria” is the word for air in Italian, and a television announcer I knew in Brussels (he’s in Love Objects) was named Pol Arias. I think of the air as being the subject of Aria. The most dramatic movement in the film to me is when the clothesline is moved by the wind. At times, the air is almost visible in the grain.

MacDonald: Did you use a double level of colour negative and black and white positive?

Chomont: Oh no, it begins with colour positive and black and white negative combined, and then later it’s colour positive and black and white positive separately, and then it ends with two flares, one of which is colour positive and black and white negative combined, though due to the flare you have little effects from that. Aria is a film that’s mostly feeling for me. This is more than I’ve ever thought or said about it to myself. I’ve always liked Aria. After I came back from my travels in the East, I hadn’t seen my films for a very long time and that one was so peaceful, so relaxing to me.

MacDonald: I like it a lot too. Many of your films are very personal and very intimate, and yet up to Love Objects you generally present eroticism in a deflected way. The viewer understands the eroticism by reading metaphors or by uncovering another level of the film. What happened that you decided to make this very direct, sexy film?

Chomont: When I was at the Museum of Modern Art in 1975, someone in the audience was saying, as I understood him, that compared to Love Objects, Oblivion seemed to be inhibited about sexuality and nudity. That may have been influenced by having some films seized by a laboratory simply because of nudity. To get them back I had to cut out whatever the lab found offensive, which included any trace of pubic hair. I was very upset by the experience but I was also determined to get around that whole thing, and it made me more obsessed with the question of nudity. What would have been incidental became more of a key issue. I suppose it led to my wanting to do it once without feeling any restraints.

Eroticism in itself is at the edges of sex. That’s a problem that porno films have made clear – showing sex is not necessarily erotic, and sometimes there can be difficulty in making it erotic. I don’t think Oblivion should have any more sex. I played with that idea in preparing the film, but it didn’t seem right. For Love Objects I had had the idea to make a film simply about genitals. I wanted to explore theirs forms and eroticism, to work with them as image. Then while I was living with the people doing yoga, we got into the chakras, and I began to think of this new film as dealing with the first chakra, the one at the base of the spine that is most connected with the earth and decay and fertility, or the second chakra, which is sex. The title “Love Objects,” came to me because I thought I would show the genitals simply as plastic forms. When I actually started filming the people, I couldn’t contain my interests to the genitals. Then the idea crystallized more into the whole juxtaposition of the metaphysical concept of love and the physical organs. There are continuing references to the alchemical allegory, Les Noces du roi et reine. Originally, I wanted the people to pass the camera around during sexual contact, to film me setting up equipment – to break all the barriers and eliminate the voyeuristic aspect of filming sex, but most of the people felt uncomfortable taking the camera, and I ended up doing only one sequence that way.

MacDonald: A lot of that comes through, though. People often look at your, and sometimes you change the lighting during shots, which is implicitly self-reflexive. Also, you’re so close in some instances that for all practical purposes you are involved.

Chomont: For a long time I thought of the film as unfinished. I wanted to form it more. Now I don’t think I’m going to go on with it. I was trying very hard to avoid stereotyping or implying any fixed roles in sexual relations, but unfortunately I think they’re there anyway.

MacDonald: It’s a mixture. There’s a place where you see a man and a woman together for the first time, and it takes some time before you realize that it isn’t two women. The confusion seemed purposeful.

Chomont: Oh yes.

MacDonald: There’s a place where you see a man and a woman together for the first time, and it takes some time before you realize that it isn’t two women. The confusion seemed purposeful.

Chomont: Oh yes.

MacDonald: The sequence near the end with the two women and the child, in the context it’s in, seems related to incest.

Chomont: Well, the two girls are sisters. It’s odd you should mention incest because they don’t look alike, and I doubt if anyone knows they’re sisters. Originally they were going to play an intense love scene together. The only reason they didn’t was because of the child, the son of a Flemish filmmaker who was living in the house where they lived, and where I was shooting, was left off by his father. Well, I wanted to have a child in the film because I really think all of these feelings go back to childhood and are even clearer in childhood – more felt, but not conceived of. I wanted him to be the child in all of us.

One of my first realizations about my own sexuality came from my recognition that as a child I desired both my mother and my father. This happened when I was visiting a friend of mine in Boston. We took mescaline, and I wasn’t ready for it. A guy was giving a very tense rap, and I was getting very upset. My friend and his girlfriend went into the bedroom; he got very sick, and his girlfriend was lying with him on the bed. I knew I wanted to go in and lie with them, just hold onto them and be comforted, but I couldn’t. I was having all this guilt, and I remembered wanting to go into my parents’ bedroom when I was afraid as a child, wanting to lie between them. I realized that a child is both sexes, he’s both the mother and the father –together they’re the child’s identity. It’s only gradually that the child is persuaded to identify more with one or the other.

MacDonald: I think that idea does come across in the film. Of course, it’s one thing to say that children are very erotic, which they are, but children in an erotic context is still taboo.

Chomont: Well, I certainly do not mean to encourage sexual relations with children. I’ve heard gasps when the child’s face first fades in, especially because it fades in just after the ejaculation in the previous sequence. I hadn’t quite calculated the shock effect, but I was happy about it because I think it’s good to realize that eroticism is continuous with those childhood feelings of wanting physical intimacy and the warmth of other people.

I’m especially happy either when people don’t know what sex to say the child is or say they haven’t thought about it. It might have been nice to have had a man in the sequence also. A woman I know said that she felt I was placing women in the motherhood role, and eliminating men. It’s not the connection I intended.

MacDonald: There’s a whole series of films made during the years after Love Objects where you seem more involved with formal aspects of printing than you were in previous films. I’m thinking of Lijn II, abda, and Re:birth.

Chomont: Yes, those were films I printed myself. I was able to play with the frame line, with the emulsion, with all sorts of elements in the printing. Lijn II is actually made from outtakes. It was originally a much more complex film, twice as long, which was stolen out of my jacket while I was traveling. I felt demolished, and then when I got back to Europe I realized I had the outtakes in a bag, so I started piecing them together. That became the film. I guess I did abda later because I felt I had never completed that first film.

MacDonald: I don’t know how to pronounce Lijn II or what the title means.

Chomont: It’s pronounced like “line,” and it means two things. The tram lies (lijns) in Amsterdam are numbered 1,2,3… I was living in a house Lijn 2 used to go by. I thought “lijn” could also mean the frame line.