Originally presented at Jihlava International Documentary Festival

Lost in Space

Ready to Cope by Aleesa Cohene 7 minutes 2006

gun/play by John Price 9 minutes 2006

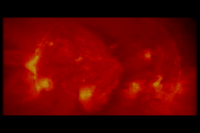

The Frequency of the Sun by Jason Boughton 10 minutes 2005

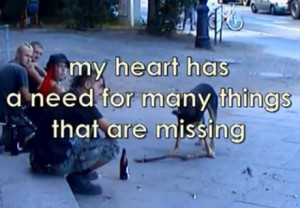

Songs of Praise for the Heart Beyond Cure by Emily Vey Duke and Cooper Battersby 15 minutes 2006

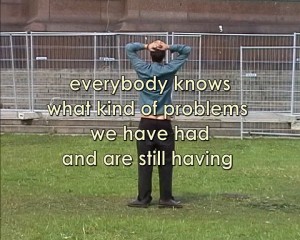

Lost in Space by Mieke Bal and Shahram Entekhabi 17 minutes 2005

A fistful of experience from the cutting edge of the fringe. Not ashamed to be beautiful, ugly, naive, stupid, hurt and lost. Where are we, the underground? Migrant workers, pop activists, American killers in Iraq: they’ve all come to take their bow, to join this festival of invisibility, to become part of your forgetting.

Ready to Cope by Aleesa Cohene 7 minutes 2006

I know what you’re thinking: please no, not another found footage compilation movie. Haven’t we been served that dish too many times already? And besides, the fruits of these labours are readily available in TV promos, best served cold in the mainstream vomitorium where they can vanish along with memory itself. But wait. Ready to Cope by Aleesa Cohene is one of a pair of movies she has spent the last three years working on steadfastly, slowly gathering pictures and then letting them settle inside her, until they become her picture. These pictures wouldn’t “belong” to her any more if she had made them herself, somehow, her role as filmmaker involves the recasting of these pictures into moments of her own life. These small instants, grown back large inside the body, then become the new alphabet which she uses to write a new story, her own story. Here is a cinema of small gestures: we see the next step, as if its viewing is a modeling or demonstration of the next step that needs to be taken, or the next breath, how to survive the next encounter. Everything is difficult, and troubled, and goes on forever, though it may appear for only a moment. Over and over again Cohene returns to the middle class home where these gestures recur (though they are never repeated), this is the sense of so many of these moments, that they are happening again, that they can’t help but happen again, that they never happened for the first time but only over and over. This sutured medley, broken and reassembled to show where the cracks are, make evident something of the strain of having to live inside this body, this house. Unbearable.

The artist writes: “ I use found footage because I feel that every experience and emotion cannot possibly be photographed. The realms of experience and emotion are infinite, yet so many of us choose familiarity and stability over risk and the unknown. I’m fascinated by how much silence and suffocation there is in each human interaction. We watch movies to feel something more than we allow ourselves to feel in our everyday lives.”

gun/play by John Price minutes 2006

There is some seeing that requires a suspension of language. Lacan might argue: of course, but the unconscious is structured like language, there is no outside. But to be able to pick up the camera prosthesis and apply it to situations which refuse language grants its beholder (first audience surrogate) a new kind of seeing-a seeing which takes place with the hands (as in a drawing class). John Price’s gun/play relishes this kind of seeing. It is set in three acts and features three encounters. As usual with John’s work, each of these live occurrences are carefully strained through personal chemistries, developed at home in the filmmaker’s bathtub, whether small gauge (super-8) or large (35mm). In the first episode John allows himself to be led by a child who turns circles with a raised toy gun. In the second a duck hunt is converted into a grainy, vanished universe of smoke and suspension. The hunter is uncovered, revealed, patiently waiting, a mirror of its image maker (like father, like son): or is it? The closing act is also its most mysterious, a return to child’s play, an enigmatic encounter with a boy on a beach. Protest or celebration: you decide.

The Frequency of the Sun by Jason Boughton 10 minutes 2005

Jason Boughton has reinvigorated the political project of the American fringe. His two deeply felt and thoughtfully constructed shorts (A Halter of Tightly Twisted Rope (16.5 minutes 2005) and now The Frequency of the Sun) were made post-9/11, an event which roused this once fringe filmer and programmer from a prolonged retirement from the image. Both his movies take aim at the American empire, Frequency deliberately conflating moments of pagan worship with Christian chorales (hymns to the son/sun). These sung interludes punctuate moments from an aerial mission from the first American-Iraq war, which is replayed to terrifying effect, recounted in a slowly drawling, looped discourse which emphasizes the way language can be bent to express the inexpressible, to make murder possible, even desirable. The American convoy has landed in a rural moment of a country where everything is incomprehensibly foreign, dangerous and difficult. Even grass looks like the enemy. They have come from the skies, parachuted down in order to lay waste to everything they encounter, gods created by technology. When they are met by a few villagers their reaction is murderous, even though some are only children. The reasons for their response are laid out in Boughton’s careful parsing of the recount, and his swaying landscapes and redigitized figures jumping from planes deliver a rhetorical corrective to more usual pictures of war which confuse proximity, even timeliness, with information.

“The key piece of music in Frequency is Vivaldi’s setting of ‘Piango, Gemo…’, an anonymous poem which describes a heart so broken, the only hope for rest is that another greater pain might come to destroy the speaker completely. But all three musics are about powerlessness-the speaker describes their own total brokeness, they surrender to it with very little expectation of mercy.” (JB)

Songs of Praise for the Heart Beyond Cure by Emily Vey Duke and Cooper Battersby 16 minutes 2006

This dynamic duo burst onto the international vid scene with Rapt and Happy (17 minutes 1998), an episodically hip manifest that was wordsmart AND you could sing along to it. Seven years on they’re busy maintaining their own high standards with Songs of Praise. There are repeated musings on animal life as the division between a cultured city momentum is pitted against the natural order of things. In one sterling sequence the camera pans over a vast, digitally frozen (and constructed?) scene teeming with wildlife as Vey Duke croons about the miracle of the bird’s annual return. Come back to this? Whatever for? Animations rework the same divide in winningly brief philosophical expositions, the artists express a clear identification with a seed sprouted too early, struggling for life. Singing lends this tape a folktronica feel, despite the machine made reliabilities, there is something very hand crafted and just our point of view about all this. If it isn’t quite as stirring as their earlier anthemic works which dared to be more personal, even confessional, this tape nonetheless finds the pair shuddering through an eloquent winter, speaking out of their mutual isolation, reconvening formal strategies familiar from some of their earlier work and pressing it into service in order to take the next step. To go on.

Lost in Space by Mieke Bal and Shahram Entekhabi 17 minutes

Armed with a twenty two page resumé and a small library of books bearing her own name, one of the brightest stars in the Dutch theory firmament has reinvented herself as a media artist. Her work carefully and ethically takes up questions of displacement and migration, and shows her willingness to intervene in a direct way, using the recording instrument not as a window or bludgeon, but a tool which can be managed from both sides of the camera. She dares to risk stagings of “the Other” without voyeurism or spectacle, shorn, in short, of the usual first world, televisual documentary empathics that continue to extrude a well meaning colonialism, Bal’s project radically reissues a challenge to these documentary commonplaces by working outside the commissioned rectangle.

In Lost in Space she unveils a panoply of speakers and places, one after another, in a kind of credit sequence. Only after the last portrait has been left behind do we hear their voices, and this displacement of sound and picture mirrors the subject of their speaking: each of these people have had a direct experience of migration, discrimination, loss and fear. But by deferring the contact high of language their statements can arrive without the visual prejudice and voyeurism that would be inevitable had we watched them “in sync,” in fact, they are more “in sync” now that they are shorn of their lip synced duty, we are more able to hear them, and they are better able to represent themselves. A bold and powerful effort from one of the new and most important voices in today’s documentary landscape.

“If we had matched the faces of the speakers with their voices, you would have an incredible problem of voyeurism with some of the people… So it was indeed an ethical issue, and to have some equality among them in spite of the very different situations among them; for instance someone who is in London because they are a professor of film studies is really in a different situation than someone who is in their own home town but in a homeless shelter. The difference is important and I don’t want to erase it, but we didn’t want to individualize it. I don’t want to de-politicize it by making them all equal. They’re not equal, and that’s clear from what they say, but it’s important that they are not considered with judgment at all as individuals, in the sense of individualism, but rather as individuals in a situation.” (Mieke Bal speaking at the Images Festival, Toronto, 2006)