November 24, 2012 Beit Zatoun (Palestinian Cultural Centre), Toronto, Canada

The Toronto premiere of Lacan Palestine was co-presented by Pleasure Dome, Queers United Against Israeli Apartheid, the Palestinian Film Festival and Beit Zatoun. Richard Fung was asked to moderate the discussion. Pleasure Dome had never screened at Beit Zatoun before, so many folks were walking into that beautiful room for the first time. The room was so jammed people sitting on the floor were squeezed right up against the wall the movie was being shown on. Earlier that week a young Palestinian boy had been killed while playing soccer, prompting a predictably futile rocket response by dissident Gaza residents. Naturally Canadian media skipped the blown up child and reported the rockets because only Israeli boys are capable of dying. If we had grown tired of the lies, we were also worn down by the certainties that had led to a seemingly endless and one-sided slow motion slaughter. And if our words and pictures couldn’t touch those imprisoned in Gaza, perhaps we might at least hold the Palestine of our own lives with some greater kindness. (This is a partial recording of the afterscreening question and answer period, made available through the kindness of Erik Martinson.)

Richard Fung: Israel and Palestine, image and sound. On the one hand your film features a cascade of images and there’s a way in which our society privileges the image, we talk about visual culture for example. But the movie’s structuring elements are in the soundtrack. It’s through the spoken word that the film offers reading instructions, or at least, a counterpoint to the flow. There’s an interesting relationship between the syntaxes of sound and picture. For me the key is the passage on jazz. John Coltrane’s group is offered up as an example of provisional community. I’m teaching a course called Local Global Mash-up where one of my students presented on Homi Bhabha. She was talking about the notions of diversity, difference and incommensurability. Underlying her presentation were questions about the ways people might live together. Jazz opens up the question of co-existence beyond a rote harmony, but it’s also a way of thinking about your work.

Mike: Could jazz, or the way we might make music together, lie at the heart of this question: how do we get along? And is it possible to get along without the usual tropes of accommodation or giving in? Without tops and bottoms, falling into line? Could the occupation turn into something else? Does everyone need to sing the same song in order for us to live together? Are there other models for how nationhood could be imagined? What was happening in Coltrane’s band, exactly? They might not be the first ones to take a bow when you think of the American black liberation movements during the 1960s. But part of the freedom they were living and experiencing and hearing in one another, and then demanding from the state, grew out of these radical adventures in community they were embodying in music. The singularities they were celebrating, where each player was allowed their own expression within the borders of the tune, was related to the singularities gathering in these new revolutionary communities. Another way of saying: black is beautiful.

It’s interesting that the gesture of black liberation turned back once again to pick up the Exodus story of Jewish slavery and liberation. The song that Paul Robeson sings in the movie is part of this lineage, it conjures a freedom that’s both individual and communal at the same time.

Richard: Could you talk about the sound-image relationship?

Mike: This is a standard definition movie so the pictures are very shabby. Unlike the beautiful, high definition images that even the cheapest portable telephones produce, these hazy pictures dim down the habit pattern of our predominantly visual culture. And with it perhaps the idea that an entire situation, no matter how complicated, can come into focus in a single moment, in a look. There it is, I have it. But when you bring down the fidelity, when the picture is not so faithful, not so monogamous, then the ears need to open, and something else becomes possible. Perhaps a different kind of conversation or a different kind of question could occur. Seeing involves grasping and knowing. I see equals I know. Whereas hearing is receiving. Little wonder our culture privileges seeing above all the other senses.

Richard: I’d like to go back to the first part of my question about your choice of this subject matter and your form. You became well known for your critical and ethical engagement in films like Frank’s Cock and Letters from Home which both won the best short film award at the Toronto International Film Festival. When I was recalling your earlier films I was thinking about the three P’s: passion, poetry and politics. But there is also a profound ethical engagement in your work. When I think about ethical media I have to call up the memory of my teacher Roger Simon who died earlier this year. He was one of the people involved in the Centre for Media and Culture in Education where I used to work. He looked deeply at the way artistic language calls up in us different ways of thinking. Some of us (I know Kathy Wazana is here) were involved in an initiative called Creative Response which wanted to bring artists and academics together to look at Israel-Palestine in a fresh way that went beyond rote responses. I’m asking the genesis question perhaps, why your engagement with the space of Israel and Palestine?

Mike: It began when John Greyson withdrew his Uncovered movie from TIFF three years ago. He was protesting the festival announcement that they were going to start a new program called City to City, and the inaugural spotlight would be Tel Aviv. This city is nearly a suburb of Gaza, you could walk, if you really had to. Earlier in the year, Operation Cast Lead slaughtered over a thousand Palestinians, many of them women and children. According to the Israeli Defense Forces it was an operation that had been planned for many months, a rigorously choreographed destruction of infrastructure, homes and hospitals. Global outrage led to Brand Israel, a cover up campaign designed to reassure the international community that Israel was a progressive, haven, the only democracy in the Middle East, that kind of thing. The TIFF spotlight was part of this campaign, as the mayor of Tel Aviv blithely announced. John’s film withdrawal was followed by a large petition that was reliably misreported as a festival boycott. It was so interesting to see how the media created their own versions of events, faithfully reflecting the interests of their wealthy patriarchs. On the ground, John’s protest lent new heat to discussions that remain ongoing.

Andrew Paterson: Can you elaborate on the voice-over that talks about looking not at the centre of the image, but at its corners or background? I thought that passage was incredibly well placed, and found myself trying my damndest to watch the rest of the movie that way.

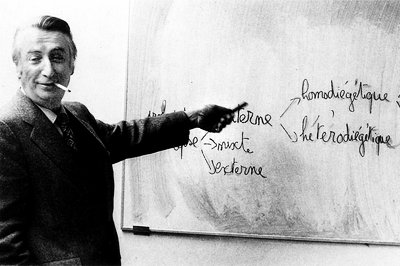

Richard: I’ll just repeat the question for people in the back. Andy’s talking about the scene that references Roland Barthes’s notion of the punctum, where you don’t necessarily look at what is supposed to be the subject of the photograph.

Mike: Barthes insists that the picture looks back at its viewer. Seeing isn’t a project that I undertake as the king of all I survey. The imperial observer deciding that I like, I don’t like, I’m neutral. Instead, Barthes poses a question. In the world of the too many pictures we live in, why is this picture irresistible to me? Barthes makes a cut, he says that most pictures belong to what he calls the studium, and while they might be interesting “I do not love them.” Such a beautiful and curious phrase. The pictures of greatest importance have some moment that looks back and wounds the viewer. That wound and opening is love, and through that aperture the photograph looks back. It’s an experience that’s different for each person, no one is struck the same way as another. Your wound, or the way you might open to be wounded, the way you might open to be loved in other words, is absolutely singular for Barthes.

An aside. One of the things I most enjoyed about this screening is that the master tape, the digital tape that I brought to show tonight, already has dropouts. A film fades and bears scratches. But digital media is either on or off, so when the dropouts occurred, there was no signal and the machine posted a blue screen with the small title: No signal. That was so great. Of course I had to wonder: is that all there is? Maybe there’s no more, and that made our time together so precious.

Andrew: It’s a bit like jazz.

Audience member: I thought it was a deliberate part of the film.

Mike: I know, I know. Typical avant gardist negation.

Audience member: I had a question about your creative process. Are these images that spoke to you, causing you to archive them? How did the images arrive?

Richard: The question is about Mike’s process of gathering and orchestrating the images.

Mike: I have to underline the incredible generosity of Elle Flanders, Tamira Sawatzky and Velcrow Ripper. These are people who have spent serious time in Palestine and Israel. I approached them with vague explanations of what this movie might be about, but as soon as it was clear that it concerned Israel and Palestine, each opened their arms and gave me all their footage. It was the most incredible thing. Velcrow offered me a large Tupperware tub full of MiniDV tapes. Apparently there was no need to make selects of the most precious and perfect seeings in order to hold them back. Elle and Tamira handed me an entire hard drive. It was so generous, so kind. It’s not just you over there making your little movie, it was as if we were all part of the same project, each of us expressing it in our own way. It was as if my singularity, the particular way that I see and hear, was entirely reliant on you expressing your singularity. We’re back to Coltrane. The notes, these pictures, don’t need to be hoarded and stockpiled, part of the project of building the state I call myself. Instead, they could be shared, and that sharing became the heart of this project.

Audience: Can you talk about one of the few extended shots in the film where a boy and a father walk together through the West Bank to get water?

Mike: Velcrow shot this powerful father and son moment caught by chance, on the street. This boy is carrying a very large water container. Why such a large container? Because you can’t just turn the tap on and let the water flow, even though the West Bank is sitting on water. Palestinians don’t own their own water, they’re not allowed, only Israelis can own water. When you live in the desert, water is a very big deal. You can see by the gesture of the father that this is a trek they’ve made many times. He waves greetings to the householders along the way. And meanwhile the son is making these very emphatic gestures on his drum, hitting it pretty hard. What I hear in that gesture is Coltrane, this is the boy’s jazz. He’s taking this duty, this sign of the occupation, and turning it into music, into a song only he can sing.

Richard: How do you keep all these clips? Do you have a notation system for the films you draw on? There’s an astounding archival organization at work.

Mike: The movie was composed in different movements. The establishment of the Israeli state for instance. Slavery. Checkpoints. I would start gathering pictures, and then you erase your private life so you can watch thousands of movies and it’s no problem, there’s plenty of time. You need time to see these pictures, and allow them to see you.

Audience member: Can you tell us about Lacan Palestine and that long kiss?

Richard: There are two long kisses actually.

Audience: The one that went on and on.

Mike: When I showed this film in Montreal my favourite question was: why are there two guys kissing? From the hundreds of clips on offer, this one carried the punctum, the wound. (Is she telling us: in order for me to be with a man, I would need to be a man.) I think each kiss in the movie is a response to the question: how do we get along? There are many models of couples on offer here. One of the kisses is ripped from a compilation movie made with Lumiére’s old camera, what is it called again? Lumiére and company. What you see is a couple making out while a history of cameras looks on, recording and recording again. As if the subject never changes, only the means of delivering the picture. Perhaps newly reseated in this movie, the scene suggests that we need to change both the way pictures are made, and what we are making pictures of.

Audience member: I’m interested in your images of father and son. The father is Israel and the law. I’m wondering if there is a role reversal suggested, that Israel needs to come home to the indigenous Palestinian population.

Mike: Part of the point-counterpoint flow of the movie is trying to unsettle some of those fixed relationships. The film returns again and again to the Old Testament story of Abraham and Isaac, shown in paintings and re-enactments. Abraham is called by God to sacrifice his son. I am called by a voice you can’t hear to take you up the mountain and kill you, but at the decisive moment, the voice reappears to stop the execution. What kind of family do we have now? This ur-relationship between fathers and sons is conjured and re-imagined. What if, instead of cruel dad duties, our longed for relationships were more like brotherly and horizontal? Could that also be a way we might get along? What kinds of pictures are we making of possible relationships, and how are those making the cover stories of our constraints bearable?

(tape ends)