“When one looks at something, one’s not only looking at it directly, but one’s also looking at it through the assault that has already been made on one by photography and film.” Francis Bacon

Though still a relatively recent activity, working with the moving image in the digital age has a history. This record resides in an evolving cultural process of looking that Bacon identifies above. It can also be referenced back to that non-narrative tradition of the moving image that runs through experimental film and video production. Although that is a practice that has become problematic in Australian conditions, an experimental/“avant-garde” tradition of film and video art continues internationally to offer critical ways of articulating the human condition, especially at those margins at which such an oppositional practice itself tends to be situated. Canada, a place with which Australia shares many parallels, offers a continuing, lively tradition in this area. Mike Hoolboom’s Tom (2002 75 minutes, Video) is presented here as exemplar evidence of such a continuing spirit. Tom , created using digital technologies, can be considered in terms of both old and new media. It is a work that has been historically informed by the work of a previous generation, like the work of film artists Al Razutis and Jack Chambers. This is a connection that will be examined further to underline the regenerative resilience of Canadian moving image art. What this ongoing tradition offers a contemporary digital practice is a fully formed mastery over technique and an articulate, mature language that speaks directly to the viewer.

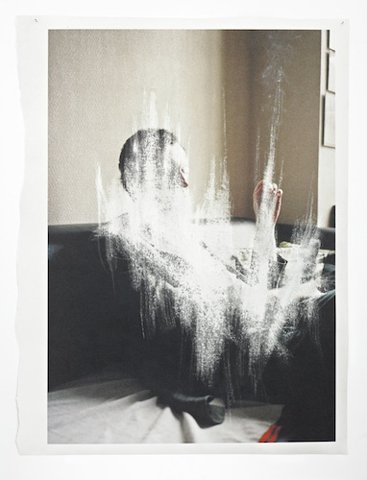

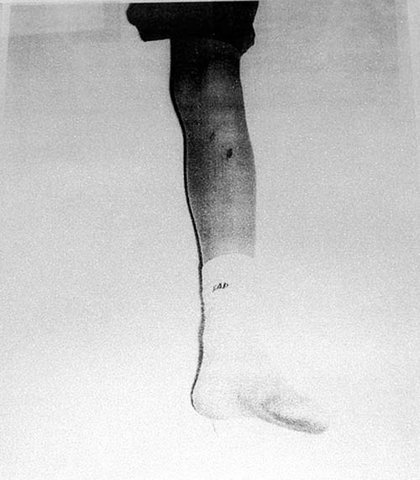

Tom is Mike Hoolboom’s biography of filmmaker Tom Chomont and his City, New York and includes excerpts of his films including Phases of the Moon (1968) and Sadistic Self Portrait (1994). Tom tells of his struggle with HIV and Parkinson’s disease and disarmingly recounts confronting memories of infanticide, incest, fetishism and death. These revelations are then processed through an array of technique, pulled out of Hoolboom’s lifelong immersion in fringe film , bringing to bear layered photos, home movies, video, appropriated archival and found footage and images directly out of the video rental store, to supply a cathartic visual processing machine. Arthur Kroker’s ideas about panic bodies and excremental culture permeate both the structure and content of this video. It is in part an examination of the erasure and loss of 80’s experimental film while at the same time re-inventing it as a resilient form of moviemaking for the digital age; A “Vital Sign” that there is a creative tradition of moving image art worth persevering with and re-connecting to.

The Old and the New

Experimental Film and video continues to flourish outside Australia in North America and Europe. It evolves and continues to be distributed through such organizations as, for example the Lux in London, Sixpackfilm in Vienna, Light Cone in Paris, Video Data Bank in Chicago and CFMDC in Toronto. Such work remains part of a line of alternative cinematic investigation, sitting outside the mainstream, and often critiquing and analysing that commercial centre. Hoolboom, as a long-term card carrying participant in this project, offers a sophisticated, confronting and historically aware renewal of that Canadian specific “cinema we need”.

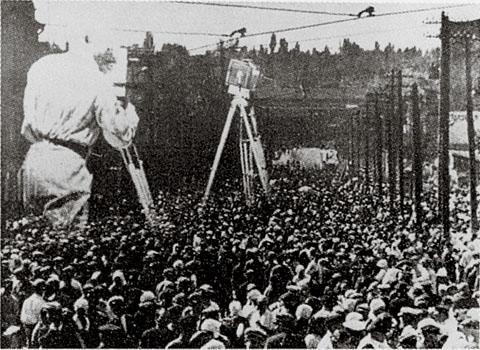

Lev Manovich creatively appropriates frames from Dziga Vertov’s Man With a Movie Camera (16mm 1929 Russia) as foundation topography for the prologue to his seminal 2001 text: The Language of New Media and further recycles these images as Interface, to signpost different sections of the text in that book. Manovich’s branding of Man With a Movie Camera as meta-film is welcome and telling and he states that: Vertov is able to achieve something that new media artists still have to learn- how to merge database and narrative into a new form. But there is a New Media myopia at work here, because a well documented international history of moving image work emerged after and “out of” Vertov. This is an apparently invisible history even to Manovich and certainly here in Australia. Hoolboom offers the latest incarnation of this “invisible cinema”.

We will further examine how Hoolboom’s Tom offers a contemporary merging of Vertov’s database and content and outline how this is a method and form already reworked by generations of experimental or personal film artists like Al Razutis and Jack Chambers in Canada and informed, in Canada by theorists such as George Grant, Harold Innis and Arthur Kroker to give this work a particular technological spin. I would suggest that in such a constellation a history for new media art is there for the taking.

Why zoom in on Canada when there are so many global possibilities? It is more than the fact that Hoolboom is Canadian and Tom is a Canadian film. It is more that a focus on Canada underlines to an Australian audience that such a practice can arise from a familiar place, a place with which we share a number of commonalities including our parallel, colonial histories. Canada offers the possibility of a dispersion of our short-sightedness.

Within the new world of such ex-colonies as Canada and Australia there is often a myopic understanding of our own history. The idea of Terra Nullus itself sets up a tradition of denial and erasure. There was plenty here before the first fleet arrived. There is a formula here that continues to be repeated. The new tends to replace the settled, the old with an associated forgetting. Such a dysfunctional tradition silently permeates all aspects of our culture, including creative and technological production. In Australia the emergence of the digital saw a concurrent collapse of critical, financial and exhibition support of experimental film, with a resulting decline in production.

This Vital Signs Conference itself is evidence that the new cycle of production that replaced it, which has been complicit in the forgetting of the experimental, now faces threats to its own funding and identity. It could be argued that such moves on digital production are strengthened because of New Media’s lack of connection to its own roots in experimental or avant-garde moving image production.

In Canada, as elsewhere, the historical connection has been maintained. Earlier on Canadian artist Jack Chambers, for example, saw personal film as an area of creative production where a colonial denial could be addressed. The problem for new world art, wrote Jack Chambers in 1969 is that it “runs the risk of an impoverished materialism through omitting the historical dimension.” But “Where North American artists do embody an historic dimension is in the medium of personal filmmaking. They form a major part of film’s “roots” and are making enormous advances in the organic-mind growth of this art.”

Kroker’s observation that the Canadian discourse on technology “is situated between the future of the New World and the past of European culture” further credentials Canada as a colonial site for examining a New/Old Media interface or amalgam. This is a status Australia shares without the lucidity and spine of Canada’s integrated fringe filmmaking activity, exemplified in Hoolboom’s work, which here as already stated has fallen by the wayside, has dis-connected in the scramble in and out of the new. An impetus to re-focus and re-claim this tradition for an enriched Australian creative practice of the moving image is overdue.

The Direct

Tom offers a timely and critical renewal and development on from previous experimental work in its ability to communicate directly to its audience through its visual imagery. This idea of “the direct” is perceived as critical to a definition of experimental film and video by Small. Small’s Direct Theory contends that experimental film as a genre does its theorising intrinsically and directly through its methods of assembly, through the making of the work itself.

Small develops a checklist to help define the genre of experimental film and video: a collaborative construction, economic independence, brevity, non-narrative structures, technical innovation, avoidance of verbal language, mental imagery and reflexivity. These characteristics make a compelling road-map for digital construction as well and Small’s characteristics of mental imagery and reflexivity are especially relevant to an understanding of Tom.

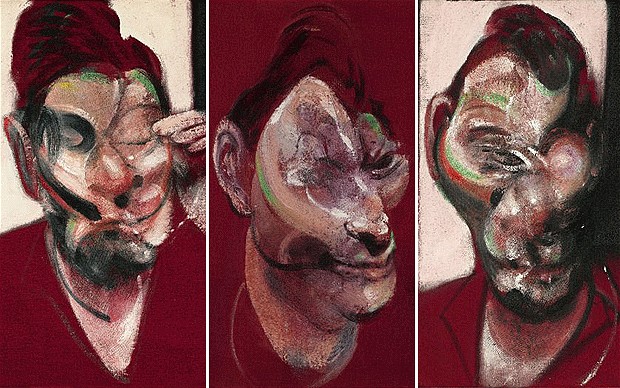

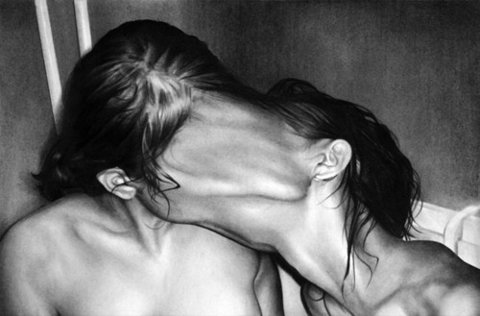

Though alien and irrelevant to popular cinema what Small brings to the surface as unique to experimental cinema is often part of the accepted wisdom of art in other media. The tactic of “the direct” is also effectively employed by painter Francis Bacon and also in the work of Jack Chambers (as will be discussed later). Bacon’s work offers evidence of this strategy in painting, photography and the space between a series of images. His paintings, are a unique and personal vision of “the body in ruins” which straddle the figurative and the abstract, and are framed by his interest in photography and cinema. Bacon’s strategies echo the way that Tom impacts immediately and viscerally through its image flow to its audience. We will examine Bacon’s ideas further before we return to the Canadian connection and its project with technique.

Van Alphen outlines how Bacon’s work, often described as reflecting the disturbed pain of the artist, also settles and imbues a sense of personal loss on the viewer. Through distortion and ambivalent representations the artist disorients the senses of the viewer and communicates directly at a bodily level to his audience.

Sylvester’s incisive interviews with Bacon relay this process in the artist’s own words. It becomes clear, for example, that Bacon has an obsession with the open mouth in his work and this is a moment appropriated from cinema. This fixation is grounded in the frozen silent shock of the nanny scream from Eisenstein’s groundbreaking Odessa Steps montage sequence in Battleship Potemkin (Russia B & W Silent 66 minutes 1925) . Within Bacon’s practice there is also a persistent returning to Muybridge’s pre-cinema serial recordings of figures in movement. This is the same immersion that occurs in Tom . There is the same historic referencing of cinema and pre-cinema in the mass of re-contextualized found footage from which Tom is constructed.

Bacon works through the photograph and memory rather than through sittings with his subjects. “ I find it less inhibiting to work from them through memory and their photographs than actually having them seated there before me .” It is a relationship that reminds one of Mike Hoolboom’s relationship to Tom Chomont. Tom’s revelations are often routed through other imagery and other representational forms before they arrive at the viewer. This imagery is often needed to absorb and process the impact of Chomont’s revelations about his life and his family.

Bacon repeatedly worked with images in series, using the triptych to create relationships: I see every image all the time in a shifting way and almost in shifting sequences. In the series one picture reflects on the other continuously and sometimes they are better in series than they are separately because, unfortunately, I’ve never yet been able to make the one image that sums up all the others. So one image against the other seems to be able to say the thing more.

The Holy Grail of the singular image is not at issue for Hoolboom as Small also indicates. Bacon is after a further distillation. Hoolboom’s focus is the moving image itself and includes its reflexive examination. His is a documentation and articulation of these changing relationships. The play of shifting sequences of imagery and subtle flow is the body of his work. He presents a string of mental imagery, externalised thought, that resonates with Bacon’s reflexive thinking about his own work. Hoolboom unfolds in the moving image that body in ruins that Bacon fixes in his painting. For both artists, the effect on the body of the audience is targeted along this shared trajectory.

Bacon regards breaking through media determined habits about the way we take in information as critical to his art: We nearly always live through screens- a screened existence. And I sometimes think, when people say my work looks violent, that perhaps I have from time to time been able to clear away one or two of the veils or screens . To achieve a direct impact on his audience Bacon’s method connects back to Russian Formalist strategies like de-familiarisation and baring the device articulated by Shlovsky. What I want to do is to distort the thing far beyond the appearance, but in the distortion to bring it back to a recording of the appearance . Small also identifies these as critical operations for experimental cinema (reflexivity and technical innovation). At its best Tom also breaks, disconnects from its screened existence.

For Bacon communicating directly to the body requires a denial of storytelling (perceived as an intellectual activity). It’s a very very close and difficult thing to know why some paint comes across directly onto the nervous system and other paint tells you the story in a long diatribe through the brain . The moment the story begins to be elaborated the boredom sets in; the story talks louder than the paint.

This tension between storytelling and some visual visceral impact also exists in Tom, where Tom Chomont’s voice intermittently breaks through the image flow to relate some event from his life, usually confrontational and/or catastrophic, offering an element of story that the imagery feeds off and takes up. The story is not being elaborated by this image flow but seem to take us to a place where the images impact directly onto the nervous system to help our bodies work through Tom Chomont’s enunciated “home truths”.

The Virtuosity of Technique

For Hoolboom this direct use of imagery arises out of his role in the project of Canadian personal filmmaking and Canadian intellectual thought. A discussion of two Canadian feature length films: Jack Chamber’s Hart of London and Al Razutis’s Amerika can help to underline a connection between the direct and technique . They too arise out of and help define a Canadian fringe filmmaking practice that is organised, technologically articulate and self aware with a critical political dimension that addresses issues of image and database re-appropriation, non-narrative structure and abstraction. It is interesting that three films also critically and self-reflexively re-deploy historical material as content.

Al Razutis’s Amerika (1972-1983 152 minutes single or 56 minutes triple-screen 16mm) is a ” feature-length experimental film which was created one reel at a time to function as a mosaic that expresses the various sensations, myths, landscapes of the industrialized Western culture (1960’s -1980’s) through the eyes of media-anarchism and avant-garde techniques .” To investigate various forms of filmic representation and their underlying ideologies Razutis uses an array of time-lapse, optical printing, video and audio synthesis techniques to interrogate the mainstream and continually re-contextualize the film’s own construction. The serial construction and the out-there confronting meshing of technique with political concerns has been taken up by Hoolboom in his work. With Tom he brings this tension clearly back into the personal.

Quite apart from the argument of its invisibility, of it having been erased, there is also an argument that the avant- garde or experimental has been neutered within new media production. What has been this repressed other to mainstream cinema; the experimental, the avant-garde, the underground, fringe cinema, graphic film and video art, Wollen’s counter-cinema, no-budget and personal filmmaking makes its prodigal return to the centre of New Media production. But the avant-garde no longer spits in the face of institutional art. The avant-garde has become materialised in the computer manifesting McLuhan’s “ all centre without margins ”. The avant-garde returns emptied of its political edge and rhetorical grounding.

Such an homogenisation can be further outlined by focusing in on a specific technique or technical strategy. Single frame time-lapse, a strategy often utilised within experimental production with an interval-o-meter attached to the movie camera, becomes a redundant coupling in the digital domain. With real time recording now seamlessly malleable, its duration shrunk and stretched at will in postproduction, time-lapse has not so much disappeared as a trick or special effect but re-emerged embedded within the form of the technology itself.

The enabling of collage through cut and paste commands, the convergence of graphics, titles, text, sound and a host of animation strategies with image manipulation and tweaking, sound and live action into computer based editing packages like Macromedia Director, Adobe After Effects and Final Cut Pro digitises the Experimental film-maker’s strategic toolbox and promises to turbo-charge her tradition. Yet it seems the prodigal returns neutered, in zombie-like fields of homogenised clones.

Having begun his project pre-digital Al Razutis’s trajectory mirrors these changes and inconsistencies. Razutis’s career long take on technology is now accessed at any computer keyboard. His drive and commitment appear to dissipate in the endless expansive fields of information overflow that can define the web.

His spraying of “The avant-garde spits in the face of institutional art” on the brand new screen at the Vancouver Cinematheque, “ruining” it forever, has long been part of avant-garde folklore. His retrospective at the Osnabruck European Media Arts Festival of old and new work in 2002 hands him contemporary kudos and relevance. Collage remains king inside the computer. Re-located online as Visual Alchemist/Activist Razutis’s project with technique continues. Yet his larger than life invocations are harder to hear, less distinct amongst the mushrooming cacophony of numerous online voices and multiple technical games.

Such a softening, diffusion or demobilization of the avant-garde’s critical edge is addressed and reclaimed in the hyper- layering, editing and collection strategies employed by Hoolboom in Tom .

Jack Chambers’painting, his writing and film work further illuminate the connection between technique and the “direct” strategies employed by Bacon. Hart of London (1968-70 80 minutes, 16mm) by Jack Chambers is a lyrical mixture of archival and newsreel footage of London, Ontario mingled with images shot by Chambers himself. The film introduces a deer that is stalked and killed in downtown London, setting up a struggle between civilization and nature that permeates the film, through its life and death cycles and the everyday images of life in London. It is through the visionary collage of this material, its superimpositions and pace that the film attains its cumulative impact and reputation: The four films of Jack Chambers have changed the whole history of film, despite their neglect, in a way that isn’t even possible within the field of painting.

Chamber’s move from his realist painting to film was realized through his silver paintings. They were concerned with transforming space to time. As the viewer moved the image fluctuated between a negative and positive image. These “instant movies” were Chamber’s response to the new demands that photography had placed on representational painting and moved him though an aesthetic history of cinema to its current technical state, which merges image and sound.

There are traces of Bacon’s “direct” cosmology in Chamber’s thinking. Chambers underlines the critical role of history when he posits that ‘Technology is a historic process that learns from itself and perpetuates what it learns by a tradition, thereby passing on the accomplishments of its own history.” Such an integrative process passes technique through Chambers and Razutis to Hoolboom, for example, and this is Manovich’s evolving database (here already in play before the emergence of the digital). Technique is viscerally integrated into the body. It is a conditioning that evolves over time to the manipulative practice, to the adaptation of results to the nervous system ” Meaning is communicated directly to the body and then, for Chambers, like Bacon, the boredom does not set in.

For Canadian philosopher George Grant this can be a difficult and critical process, especially in the colonies. The tension at play concerns the margins resisting the centre. “ We can hold in our minds the enormous benefits of technological society, but we cannot so easily hold the ways it may have deprived us, because technique is ourselves ” . For Grant the modern self is being colonised from within, perhaps mapped as Foucault’s technologised self and McLuhan’s body extensions and connects with Van Alphen’s reading of Bacon as loss of self. Loss becomes difficult to express within such technical topographies, though Parker Tyler has observed that “ The void itself is a ground .” It is at such blind spots that Bacon or Chambers can inject their vision directly into the nervous system and Bacon can elicit the “exhilarating despair” of the repressed “other” coming into view.

Grant implores “only in listening for the intimations of deprival can we live critically in that dynamo. We need to articulate a world of “dead identities, dead vision, and an overwhelming sense of inner dread and anxiety”. Artists whose inner life is infected by displacement and rage (Razutis), leukaemia (Chambers) and HIV (Hoolboom) are well placed to use their colonised bodies (their Panic Bodies) as database to directly articulate such depravity. When the site of such activity takes place within a colony that itself acts as a victim , artists need to develop a layered vision to articulate and transgress that implosive situation.

Chamber’s articulation of his creative practice as Perceptual Realism seems to parallel Kroker’s reading of another Canadian thinker, Harold Innis’s work as Technological Realism. Innis “sought to preserve some critical space in Canadian discourse for the recovery of an authentic sense of time” Innis argues that to foster a stable western culture like Canada, the countervailing centrifugal and centripetal forces of time/duration and space/territory need to be in balance. The migration of technique from the United States, as advanced technological society, to Canada (as advanced dependent state) is evidence of the triumph of the colonising monopolies of space: the global electronic media that is seen to be in need of tempering by a cultural impulse to recover time, to remember.

Now at the post-modern (articulated by Kroker with his compacted swaggering prose, akin to Hoolboom’s gung-ho layered pastiche of image and technique) the fault lines between time and space have heated and morphed the hype into hyper: hyper-drive, hyper-real, hyper-space, hyper-aesthetic. This is the triumph of technique as the post-modern (Razutis’s legacy): the current container of Capitalism’s “progress”.

Within Innis’s cultural script the personal cinema of Chambers and Hoolboom especially can be read as a bulwark, enabling authentic civil discourse, a cultural remembering within Canada by re-ordering the debris of commercial media activity. Unfortunately for Razutis his displacement to Canada as “asylum seeker” from California retraces the trajectory of technique itself and thus performs a double whammy on his enraged body. There is a trace of Hoolboom’s relationship to Razutis in the subject of Tom; New York experimental filmmaker Tom Chomont, which allows for a revitalisation of Razutis politically charged project.

Summation

And so we arrive again at Hoolboom who, like Razutis, also had his stint in Terminal City. His “Three Decades of Rage” acts as witness advocate and fan to Razutis’s rant and his affiliation to the Escarpment School in Ontario accesses the pedigree of Chamber’s leukaemia terminated project. His layered database consists of the history of Canadian reflexive thought, a life lived in North American avant-garde film, his own activism within its making and the daily reminder of his own HIV colonised body. This database is directly incorporated into the body of his work, re-constituted in the biography about biography that is Tom.

Tom salvages the media detritus that we all consume in our daily lives and transforms it into the matter of some externalised mental bustle that is personal and unique. It is not garbage in, garbage out after all. The neutering of the avant-garde at the moment it is enabled within the computer does have a twist, it does not have to be “terminal”. Hoolboom has figured out how to turn his scavenged shit into gold and meet Grant’s challenge in a post-modern context by listening to his body.

It seems as if the surface of cinema itself is the body that is being marked and reconstituted and “the personal” forever challenged and changed by the infection of this material into the psyche. As observers there is a directness about this infection that makes it our infection, bubbling away in our heads, eyes, heart and so on. We can walk away from the cinema and our screens with that self belief back in our bodies; that the tools, the strategies, the technique can be found to re-invent our selves out of the “new chaos” that Kroker maps out: “unlike billboards in the age of pavement, these advertisements are injected directly into the veins of the post-flesh body like bar codes burned into flesh ” There is value in history after all. This is what Tom gives to me.

It can happen here. It has happened before.

Dirk de Bruyn

July 2005

Notes

Sylvester, David. Interviews with Francis Bacon Thames and Hudson London 1975: p 30

There are a number of terms that are used interchangeably: fringe film, personal film, experimental film and video, film and video art. This reflects a kind of homelessness for this area of art production that now seems to be also reflected in what is now happening with terms like new media, digital media, multimedia, interactive art and so on.

See Kroker, A., M. Kroker, and D. Cook, Panic Encyclopedia: the definitive guide to the Postmodern Scene. CultureTexts, Macmillan Basingstoke 1989

Kroker, A. and M. Kroker, Body Invaders: Sexuality and the Postmodern Condition . Macmillan Education Basingstoke 1988

Kroker, A. and D. Cook, The Postmodern Scene: Excremental Culture and Hyper-aesthetics . 2nd ed. St. Martin’s Press. New York 1988It is understood that a number of readers may not have had access to a screening of Tom, especially Australian readers. For those there are descriptive elements in this text that leave a trace of the work. Yet even this video’s absence from view creates its own mischievous impact on discussions about erasure, denial and forgetting. I think the primary task is to make the argument for re-connection can be effectively enough understood without a viewing of Tom.

see http://www.lux.org.uk/ > viewed 8 November 2005.

http://www.sixpackfilm.com/?lang=en&p=info > viewed 8 November 2005

http://fmp.lightcone.org:8000/lightcone/us/acc-us.html > viewed 8 November 2005

http://www.vdb.org/default.html > viewed 8 November 2005

Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre Website: < http://www.cfmdc.org/ > viewed 8 November 2005

See Elder, Bruce. The Cinema We Need

in Canadian Forum Vol LXIV No. 746 (February 1985) pp 227-243. this article that was critical to a discussion around “the cinema we have” and “the cinema we need” that occurred in Canada in the 80’s

Manovich, Lev The Language of New Media Cambridge, Mass. ; London: MIT Press, 2001: p 243

see: Grant, G., Technology and Empire : Perspectives on North America . House of Anansi. Toronto. 1969

See: Innis, H.A., The Bias of Communication . University of Toronto Press. Toronto 1952

Innis, H.A. and M.Q. Innis, Empire and Communications. University of Toronto Press. Toronto 1972

Arthur Kroker’s own (Kroker, Arthur Technology and the Canadian Mind Innis/McLuhan/Grant New World Perspectives Montreal 1984) is a good overview of this tradition and indicates how these thinkers are connected to each other. In fact Kroker’s relationship and building on the thinkers he investigates compliments Hoolboom’s (and others such as Phil Hoffman and Barbara Sternberg) relationship to Al Razutis, Jack Chambers, Rick Hancox,

Joyce Weiland, Michael Snow and others.

Chambers. Jack in Elder, Kathryn (ed) The Films of Jack Chambers . Cinematheque, Ontario 2002: 35

Ibid: 43

Kroker, Arthur Technology and the Canadian Mind Innis/McLuhan/Grant New World Perspectives Montreal 1984: p 7

Small, Edward Direct Theory: Experimental Film as Major Genre Carbondale : Southern Illinois University Press, 1994

Ibid.

Van Alphen, Ernst . Francis Bacon and the Loss of Self Reaktion Books London 1992

Sylvester, David. Interviews with Francis Bacon Thames and Hudson London 1975

Sylvester, David. Interviews with Francis Bacon : p 40

Ibid: 21

Ibid: 22

Ibid: 82

see Shlovsky, Victor. Art as Technique in The Critical Tradition. Ed., David H. Richter, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989

Ibid: 40

Ibid: 18

Ibid: 22

see Al Razutis Website: http://www.holonet.khm.de/Visual_Alchemy/film_cat.html#amerika viewed 9 November 2005

Manovich, Lev The Language of New Media : p 307 -to paraphrase Manovich’s: In short, the avant-garde became materialised in a computer.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media:The Extensions of Man. McGraw-Hill Toronto 1964, p 2

Brakhage, Stan in Elder, Kathryn (ed) The Films of Jack Chambers. Cinematheque, Ontario 2002: 45

Chambers, Jack in Elder, Kathryn (ed) The Films of Jack Chambers. Cinematheque, Ontario 2002: 47.

Ibid: 13

Ibid: 35

Ibid: 35

Grant George Technology and Empire : p 137

Quoted by Kardish, Larry in Elder, Kathryn (ed) The Films of Jack Chambers . Cinematheque, Ontario 2002: p 186

Sylvester, David. Interviews with Francis Bacon Thames and Hudson London 1975: p 83

Grant George Technology and Empire : p 142

Kroker, Arthur. Technology and the Canadian Mind : p 22

Margaret Atwood makes this argument in Survival : A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature House of Anansi Toronto 1972

Kroker, Arthur. Technology and the Canadian Mind : p 124

A partly endearing moniker for Vancouver.

Hoolboom, Mike. Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada . Gutter Press Toronto 1997: pp 56-73

Kroker, Arthur and Weinstein , Michael A. Data Trash: The Theory of the Virtual New World Perspectives, Montreal 1994: p 109