John: When did you begin making films? What were your first films about?

Mike: The question of beginings haunts me, and I can hear a shadow of it in your query too. The commonplace says that a woman’s relation with creation is embodied, certain, physical and finite, while men are condemned to speculation, fiction and anxiety, not necessarily in that order. Hence the telling of stories. Let me tell you one. It took me a long time to learn language. My parents were patient, my school instructors redoubled their efforts, pointing to familiar objects and creating strange sounds out of their mouth holes. Sometimes I would clap, as if they were conducting concerts dedicated to a solo audience member. I tried to be appreciative. Sometimes I would stand on chairs and tables and hurl my meat hands together as I had seen others do, but the result was only disappointment. Slowly and reluctantly their word viruses entered me, and I took my place in the tribe, repeating the same phrases as all the others, as if they could speak my truth. The rulers at Starbucks have learned this simple lesson: make them say grande, change the language, and that will change the whole world. It changed mine. I began to dream only in words, this is how my acquisition of language finally began. All night words would come to me, singly and then in showers, and after many years of this I was startled to learn from my comrades that they dreamed only in pictures. Pictures? I think this is the moment when my movies began; in order to see anything but the virus, I would have to create these pictures myself.

John: Whom are some of your favorite films and filmmakers?

Mike: I like the film that the large silver maple makes in the park across the road. Every day it holds the same position, it offers the anchor of a view, a look out. I love the movies of the Canadian poet Anne Carson because she allows me to make my own pictures. And when I go to the movie theatres and backrooms and pop ups that show fringe delicacies I am wondering at the raw encounters of Dani Leventhal (Tin Pressed, Draft 9, Hearts are Trump Again) and Eva Marie Rødbro (I Touched Her Legs), the political poetry of the Otolith Group, Susanna de Sousa Dias’s rigorous commitment (48) and the endless inventions of my friend John Greyson, who is languishing in a Cairo jail right now waylaid from his Gaza mission, all for the sin of working in solidarity with the Palestinians. He has stood in the fire and looked back, and continues to make work from the most necessary places.

John: Which of the arts are you most partial to?

Mike: It’s an odd expression you use: partial to. Not: this is what I love, but this is what I might love, depending. I wish I could hear the notes in jazz, follow the lines in dance, instead it’s books and movies that summon my parts. I have tried to follow Steve Reinke’s example and find every motion picture pleasing, but half way through Shark Week I lost the feeling, even when I had stopped looking at the pictures and only read the closed captions.

John: What do your films hope to convey to the viewer?

Mike: I’ve been working for more than three decades, how does that play as a soundbyte? Palestinians are also waiting. Being a bonobo (vegetarian matriarchal apes lubricating social relations with casual, gender-free sex) means never having to say you’re sorry. Friendship is light. Don’t stop, especially when you reach the end.

John: Do you draw or paint?

Mike: Not even when I’m dreaming. Though most of my best ideas come when I’m asleep. When I read John Berger it makes me wish I had developed the necessary muscles. Drawing and painting: such direct forms of expression. I feared painting for years, convinced I would spend too long deliberating over which abstract colour blobs should live in the same neighbourhood. I had such a strong instinct of pleasure around painting that I made sure to avoid it entirely.

John: Could you tell about the shooting of your film Lacan Palestine (2012)? What does the film say about psychoanalysis and war?

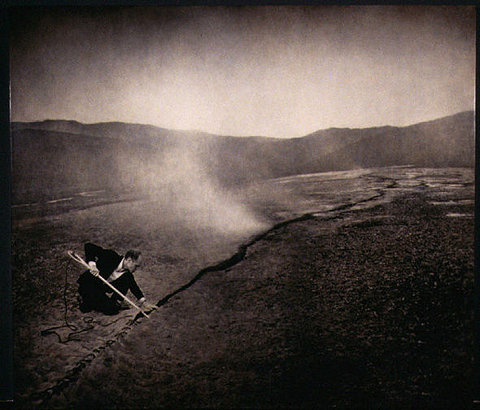

Mike: There has been so much shooting in Palestine, will it never end? Unlike John Greyson, I couldn’t muster the strength to face the tunnels, the detentions, the looming threat that hovers over the world’s largest open-air prison, so instead I relied on motion picture comrades like Elle Flanders, Tamira Sawatzky and Velcrow Ripper. They threw their voices and I was ready to receive, to let their conversations flow into my mouth. Everything in the movie is borrowed and second-hand, it’s all been done before, and now it’s happening again. Palestine appears as a country of imperial projections, another stretch of olive grove and desert to plant the flags of the Romans, the English, the Americans, the Israelis. There are newsreels which are narrated, as always, from the point of view of the occupying power, English in this instance, which names as “terrorists” the armed Israeli insurgents whose first act of national liberation would be the massacre and expulsion of Palestinians.

The land of Palestine, where Palestinian farmers worked for generations, was named and renamed for centuries, and when the Ottoman Empire planted their standard and the coffers went soft they decided to sell the land they had claimed, and this inspired a zealous landgrab that begins again with each new Israeli settlement that is built.

Can a country have an unconscious? Certainly there are some countries that are inhabited by ghost populations. I’m thinking of course about Vietnam, a country that led news reports for a decade during a brutal incursion they named “The American War.” I never saw a Vietnamese man fall in love, I never watched a father play with his sons, I never saw a woman skipping stones. Night after night the country was evoked, conjured, pointed at, but there was never enough time to show a Vietnamese person speaking. Would it break the spell? Last week a friend was trying to convince me that mainstream press coverage about Palestine was newly balanced, and offered as evidence the words of a powerful American which the paper had printed. Yes, the papers are full of words by powerful Americans, the world is filled with their thought balloons, but I am still waiting to hear from a single Palestinian locked up in Gaza City. Half the population there are children, as you probably know. As the great Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish wrote, “In her absence I created her image.”

John: Could you tell us about your film Imitations of Life (2003) which is considered a landmark in cinema? How was the film made and what did you hope to convey?

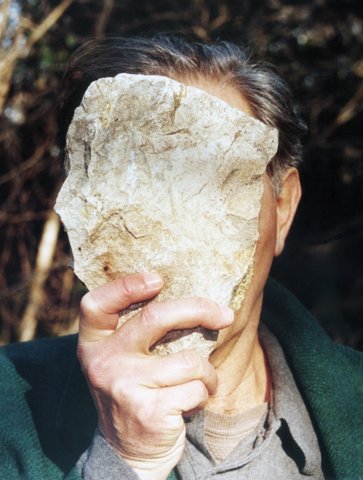

Mike: One day I woke up and there were children all around me. I never knew about this world of beginnings, where everything is seen for the first time. Even my sister had a child, and when we hung out together he taught me some of his special talents, for instance, the magic of discovering what you see every single day as if you’d never encountered it before. Meanwhile, I couldn’t help noticing that he sponged up fave words and picture appetites and food inclines. I began to see movies as inheritance and science fiction, because they projected worlds that my nephew would grow up into. Whenever I would see Jack (my nephew), I brought along a wind-up film camera and exposed a little footage. Film is very expensive so only a minute or two per annum rolled past the gate, that’s all. This went on for years until he was too busy making pictures of his own with his hands or his effervescent thoughts, and then I knew it was time to put the camera down and begin cutting the movie. That became the opening chapter of Imitations of Life. It is a movie made in parts, like a house with many rooms, or a book of short stories. My nephew is the main character, and he wanders through rooms where cinema is being born (one of Imitations’ rooms is made entirely out of Lumiére movies), where music videos are rescued, where a brother and sister play a deadly game, where a man paints a wall even as he unpaints it. Most of the footage is “found,” or stolen, because this is how Jack received words and experience, as something already chewed over, which he then absorbs and reboots. He showed me how personality is a collage artist’s best friend. The longest section of the movie offers a clip collage from science fiction futures, it is the future as we used to think of it, a future we can be nostalgic about now. What kinds of pictures do we need, what kind of bodies do we want to live in, can we find acceptable? How can we create a culture that is not filled with dreamy and merciless ideals that urge us to self-punish for never being enough? Bring me the best running shoe, the fastest car, the ideal man. Or not. How did Wallace Stevens put it? The imperfect is our paradise.