After I had finished Imitations of Life (2003), a feature-length clip collage that included every movie I had ever seen, and many I hadn’t, I was asked to program some movies for Berlin’s longest running independent cinema, Kino Arsenal. My friend Kika came and showed her excellent things, there was a long reading from Marguerite Duras’s harrowing story about how she overcame her word freeze so she could uncover The Malady of Death (1982), we reprised Imitations, sat awed at the wonder of Apichatpong’s (Call me Joe) Mysterious Island, and thrilled to Kim and Lisa’s Blood Records. The Canadian Embassy came forward with snacks, and everybody went home more uncertain than ever before. We wouldn’t have wanted it any other way.

Kika Thorne

The work of Kika Thorne follows a trajectory from the private to the public. Each of her films carries a diary address and arises from personal encounters, or as Kika describes it, — just hanging out. These casual, low-tech documents of the underclass come armed with a barbed politic, whether in the sexy feminism of her early work or the address to urban homelessness in her more recent efforts.

You=Architectural (11 minutes, 1991)

Whatever (21 minutes, 1994)

Year Book (3 minutes, 1997)

Kathy Acker in School (8 minutes, 1997)

Mattress City (1998, 8 minutes, 1998) (co-directed by Adrian Blackwell)

Work (11 minutes, 1999)

October 25th + 26th, 1996 (8 minutes, 1996. Project by the October Group)

Kika Thorne will attend the screening to introduce and discuss her work.

The Blood Records: written and annotated by Kim Tomczak and Lisa Steele (55 minutes, 1997)

The Blood Records is a ghost story, a tale of love and legislation, whose specters call from the other side of history with Hamlet’s last words: Remember me. Like all ghost stories, this one offers passage back into an underworld of dark roots, where plagues and war appear as convulsive echoes of the present, grown familiar despite our traditions of forgetting.

The Blood Records: written and annotated is a 55 minute videotape completed in 1997. Classically structured with a prologue and three acts, it narrativizes the first great plague of the twentieth century: tuberculosis. Begun in the fields which surround the sanitarium of Fort Sans, its tumbleweed rendered white through overexposure, the screen appears as the blank apron of the past before stories enter to give it shape, underscored by blues maestro Leadbelly singing TB Blues. The first act features a montage culled from educational films which pit two spaces against each another: the intimate corners of home (scrubbed to a Hardy Boys shine) and the cool interiors of the science lab. While home is figured as the site of contagion, doctors and scientists work to uncover the source of this mysterious ailment. The stentorian voice-over, hang-over of the documentary form Grierson would popularize in Canada during the Second World War, offers a familiar mix of information and moralizing, warning its viewers about the perils of reception.

The videomakers turn then to the capitol of Saskatchewan, using aerial pans of the legislature and newsreels showing the swearing in of Canada’s first socialist government under Tommy Douglas. It was Douglas’s radical vision which demanded that health care be extended to all Canadians. Commissions were raised to study the population (over half the children in the province were found to be infected by TB), mass x-rays performed, resources pooled to provide treatment.

The second ‘act’ is set in the sanitarium where patients are viewed taking their rest cures, these quietly observational moments underscored by a haunting violin measure and joined by white flashes, incendiary moments of white fever punctuating repose. Superimposed titles narrate the day’s regimen, as doctors and nurses confer, check x-rays, prepare the morning’s meal.

The third act begins in darkness, with the voice of Marie, committed before adolescence to the sanitarium, recalling her experience from the far shore of the present. Family life appears in colour vignettes, posing for portraits, or gathered to eat before her brother sails off for war. Over her recollections the dominant formal trope is a virtuosic superimposition, moments of found footage erupting from prairie fields or the sanitarium, these places of waiting become a stage for reflection. Like the patients themselves, this is a landscape of ghosts longing for remembrance. For mourning.

Mysterious Object at Noon by Apichatpong Weerasethakul (83 minutes, 2000)

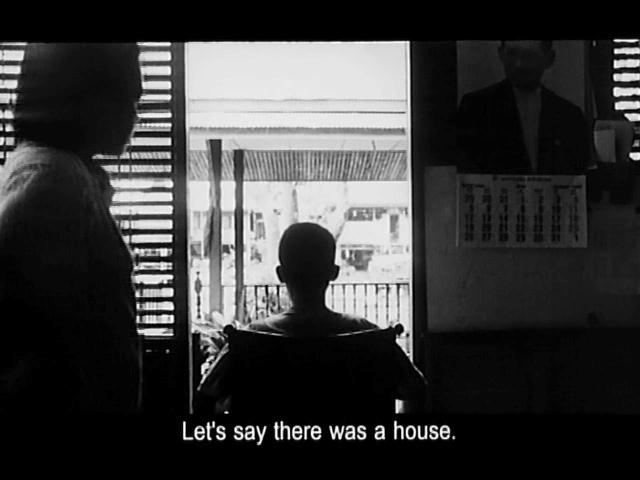

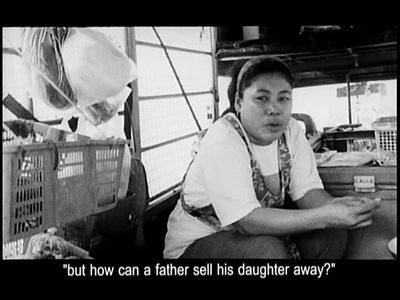

Thai filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul likes to say that Mysterious Object at Noon is really about “nothing at all.” So much for documentarians only wanting to tell the truth. Modestly produced but expansively imagined, the film was shot on 16mm in black and white, then blown up to 35mm for international exhibition. That a Thai film—particularly an experimental one—actually anticipated an international reception is strange enough: Until last month, when the flamboyant cowboy melodrama Tears of the Black Tiger became the first Thai film ever to play at Cannes (where it was promptly snapped up by Miramax, God help it), the number of Thai movies intended for export on an annual basis was roughly equivalent to the number of Samoans in deep space. Far from an empty vessel, the film encourages an ever increasing proliferation of odd topics and perspectives. Its Thai title, “Dogfar in the Devil’s Hand,” could refer to the type of overwrought, underproduced, and impossibly clichéd melodramas that have historically made up the bulk of Thai cinema, but there’s nothing archaic about the way it superimposes bits of local television dramas, pop songs, daily-life dilemmas, and improvisatory Thai theatrical conventions over the deranging pretext of André Breton’s old party game, the Exquisite Corpse.

Not that there’s anything inherently Thai about Breton’s famous “automatic writing” template, where writers sequentially contribute words to a text, largely oblivious to what came before (even though Thailand’s fine-arts community has long been absorbed by the Surrealist visual imaginations of Dali and Tanguy). But then the 31-year-old Apichatpong—born in the small northeastern city of Khon Kaen and educated at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago—isn’t your typical Thai guy. For starters, he’ll ask you to call him Joe.

“I’m interested in the possibilities of involving both fact and fiction in one film,” Joe said at the Rotterdam Film Festival, where his film debuted a year and a half ago. “But I wasn’t thinking much about revolutionizing the narrative method when I started making this film. In some ways, I think the movie turned out to be really rather old-fashioned.” Spiraling out from Bangkok across a variety of sandy southern and rural northern extremes, Mysterious Object at Noon searches out everyday people—fish sauce vendors, wizened grannies, video-game-saturated schoolchildren—who are willing to reveal bits of themselves for the camera, and to contribute a fragment to the film’s evolving story about a paraplegic boy and his unpredictable tutor, a woman named Dogfar. Initially observing his subjects at a modest verité remove, Joe then steps in to direct and intercut dramatic re-creations of the freely associated narrative strokes they’ve supplied.

Strange as all this might sound, stranger still is Joe’s position in contemporary Thai film culture, where the terms film and art rarely coincide. Cofounder of the Bangkok-based Kick the Machine, an artist-run film production and distribution company focused on young experimental filmmakers, and codirector of both the Bangkok Experimental and Short Film and Video film festivals, Joe has already earned a reputation as Thailand’s leading supporter of new filmmakers. Joe is currently at work on his first fiction feature, Blissfully Yours, a three-hour-long love story that unfolds in real time. “It’s just a sweet romance,” the director remarked last week via e-mail. “No politics.” But given the film’s setting—a picnic on the extremely volatile Thai-Burmese border—it sounds suspiciously like one more of Joe’s sweet little nothings at all.” (Chuck Stevens, Village Voice, June 19, 2001)