My general policy with the interviews for this project has been to maintain the anonymity of my subjects so that they can speak freely of yoga injury experiences that involve particular teachers and studios without fear of social, professional, or legal reprisal. But some subjects don’t need this protection, either because they are not dependent upon professional yoga culture, or because they are personally able to clear their stories with the people they reference, or because they bring a certain expertise from beyond Yogaland that we both feel would enrich the conversation. And, of course, they have to also want to be on record. My interview with Mike Hoolboom – or his interview of me – fits the bill here.

Mike is one of the world’s leading avant-garde filmmakers. His haunting work uses found footage to explore transitional spaces, sexuality and impermanence. Film critic Tom Waugh says: “For more than two decades Mike Hoolboom has been one of our foremost artistic witnesses of the plague of the twentieth century, HIV. A personal voice documenting and piercing the clichéd spectrum of Living With AIDS from carnal abjection to incandescent spirituality, no surviving moving image visionary surpasses him.”

As with so many people one orbits around in the yoga and meditation scene, I didn’t know about Mike’s professional life. I just knew him as someone who came to practice radiating some unnamable need. He was the quietest dharma sponge of Centre of Gravity, sitting like a statue sculpted from air, writing full transcripts of Michael Stone’s wide-ranging talks in pristine shorthand characters so small it looked like his fountain pen wasn’t even moving. Mike watches things with wide-open eyes.

I’m happy to know him a little better now, and to feel him use his penchant for detail, texture, character and backdrop – filtered by his hard-won understanding of bodily vulnerability under the pervasive assault of time and politics – to describe his experience of yoga through the years.

Mike: Slavoj Žižek noted recently that the New Economy requires flexible workers. He was referring of course to multiple employers, migrating job sites, the abolition of weekends. But couldn’t this also be read as a call for more yoga? I can see the boardroom heads already nodding yes. “And let’s put in a meditation room for the overachievers while we’re at it!” Žižek’s riff made me wonder if there wasn’t a fit between yoga’s newfound popularity and the rise of globalized capitalism. Perhaps it’s only a coincidence. But the ongoing conversion of downtown real estate into yoga studios brings to mind a koan by my friend Simone Moir who runs the Parkdale Prana Room. She assured me, “You can’t teach yoga. All we can do as teachers is share our maps.” Yoga might mean knowing what’s happening in your body and then finding an external geometry that rhymes. How can you do that with a stranger standing at the front of the room offering a succession of poses? How can I become my own authority if I keep leaning on experts?

I’m not a yoga teacher and was never trained in anatomy. So yoga has been tremendously helpful for articulating certain moments of the body, and translating sensation into language. But at the same time there are so many things going on in my body that are mysterious, including: “What pain is good pain, and what pain is not good pain?’”

Matthew: If there was to be a “good pain,” what would make it good? Where would it lead?

Mike: Good pain means that I’m in pain right now, but I haven’t woken up with it tomorrow. It’s a temporary guest, instead of a permanent kink in the plumbing.

Matthew: So on the morning after you’ve not only returned to neutral, but you’ve gained something from that discomfort?

Mike: Yes, I’ve been able to sit with the pain and not overly identify with it. There are patterns of sensation coursing through the lumbar spine, but those patterns are not me, myself. They’re not something that needs to be claimed or owned, like a deed of land.

Matthew: Are you also describing a type of pain that can be good because it’s not so overwhelming, and it can be used to acclimatize? “I was able to withstand that, it didn’t damage me, and now my response time is a little more expansive?”

Mike: I think so, though when I hear you put the aerial quotation marks around “good pain” it makes me wonder if I’ve swallowed too many Lululemon ads. My yoga life started out of friendship. My friend Gary decided, at a catastrophic moment in his life, to go through teacher training at Downward Dog, which at the time was a fearsome nexus of Ashtanga orthodoxy. Each Wednesday morning Gary dropped off his son at the Alpha Alternative School, and then he brought a couple of moms and I down to the basement to learn Ashtanga’s primary series. Every time we practiced it was painful. Is the body supposed to do this? Over time, some of the postures grew less difficult, while others were dropped from the repertoire as none of us managed even a likeness. I associated yoga with asana and asana with pain from the very beginning. It suited too well my core story of “not-enough-ness.” And it rewarded qualities like hard work, striving, overcoming, diligence and perseverance: values that I’d absorbed from earlier school systems.

Matthew: As you were going through pain in the primary series, did you feel as though you were being cleansed of something, or was it a matter of proving your capacity for hard work?

Mike: There was no cleansing involved, I never learned to divide the world between what was clean (and good and beautiful) and what was dirty (and disgusting and bad, and perhaps all the more desirable for it.) Pain reconnected me to my body. It’s pretty usual that we wake up to a moment of our body only when it stops functioning. When we’re sick in a particular way. “Oh my shoulder!” “Oh my liver!” I didn’t have a liver until it stopped working properly. Before yoga, illness had already taught me about waking up through pain.

Matthew: It’s startling because the moment of pain or realization of illness is two things at once: a moment of presence, as in “I didn’t know that was there,” or “That’s part of me too, and it’s suffering, and I can connect with that.” But at the same time, pain and illness are the marks of a body that cannot do what your agency would have it do. So pain brings you into contact with a formerly absent thing, but then puts “you” in opposition to it.

Mike: I think there’s a quality of surrender, or the way they like to call it in yoga — “trusting the form.” I’m not super-religious, but the dominant religious iconography in my childhood depicted a man who’d been tortured and wounded, nailed to a cross…

Matthew: …as a sign of love.

Mike: Suffering must be like love — look at that guy! The man on the cross leads me to wonder about the front of the room. Who do we put at the front of the room? Is it the one with all the muscles, the very smartest, the one with the smoothest pitch? Yoga teachers are embodied ideals. The British psychoanalyst Adam Phillips reminds us that ideals in our culture are often used to punish ourselves. “I’ll never be that smart. I’ll never be that flexible. I’ll never be able to speak those beautiful sentences.” Most of the time, that very traditional view of ideals has been at play in the asana classes I’ve been to. Though there are exceptions. For instance: Christi-an Slomka’s work at Kula Annex. She’s doing something different at the front of the room that allows me to do something different on my mat. She’s modeling her uncertainty and mistakes. It’s become important for her to project those less-than-perfect qualities. Her decision to put something short of ideal at the front of the room is a political decision. “Wait, wait, is that my teacher expressing doubt, inability, even failure? Wow. That gives me permission to fail. That makes my failings ok.” Instead of only giving me permission to succeed, which is just another form of punishment. Because what if you don’t succeed? Oh, then you can play those old self-punishment tapes again, the ones that never sit on the shelf long enough to collect dust.

Only showing our strongest, shiniest face at the front of the room, at the front of a yoga room for instance, seems directly related to over-striving and injury. When I’m given permission to stop practicing right at the edge of my abilities, to stop pushing to the max every instant, to take child’s pose because that supports the whole group, it means that I can respond to patterns of sensation in a new way. I don’t have to push away or push through the pain. I can make a space for softness and inability, and say yes to that. I think this leads to greater embodiment and less injury, but I’m only speaking for myself.

Matthew: About the person at the front of the room. The paradox might be that that’s the person who is most able to hide or sublimate the pain they are already in. I’m just at the beginning of this interview process, and you’re the first of about twenty subjects who’s not a yoga instructor. There’s a repeated story of instructors being injured, or knowing something’s not working, and being enslaved by the tyranny of happiness they’ve been hired to provide. They put themselves in positions in which they feel like frauds. Or they project their own sublimation of pain onto their students in terms of a skill to be developed.

Mike: Just a few days ago I was chatting with a friend who is a yoga teacher at a thriving downtown studio. During self-practice she was adjusted far too deeply by a studio colleague and was injured as a result. I couldn’t help asking, “Did you tell this person you were injured?” “No, I didn’t.” Several months later she’s back in self-practice when the same person performs the same adjustment and she gets injured again. “Did you tell them after the second time?” Of course the answer was no. We work so hard to protect the people at the front of the room. Is this a version of Chomsky’s observation that the poor always have to pay for the rich? It means having a difficult conversation and creating bad feelings that may never leave, and who needs that? But it might also mean losing faith in the entire project. Haven’t I come to the yoga studio to experience some newly customized version of my parents? If the parents don’t really know, then… what am I doing here exactly?

I want to say this person’s name out loud but I can’t. I must also do my part to protect the yoga teacher who injures. But my friend assured me that her injury forced her to find a new way to practice, and that this was a good thing. I’ve heard this song before. Certainly this is why Christi-an is doing slow-motion yoga, creating almost moving poses out of the spaces between postures. And then there’s my pal Lana describing a moment on a recent retreat. “I saw all of these people doing yoga acrobatics, while I was just trying to put my arm in the air and feel my shoulder joint.” So I asked my injured friend, “Did this change in your practice shift your teaching?” She said, “No, that’s not why people come to this studio. They don’t want to practice that way.” Which made me wonder: how would you know that? And what does it mean that even colleagues who are injuring each other are unwilling to have the difficult conversation that begins with “You hurt me”? If colleagues can’t talk the talk, how are we merely mortal students ever going to manage in a studio culture with non-existent feedback mechanisms?

Matthew: If we’re speaking about the more rigidly formulated yoga styles, the dominant narrative is that the practice isn’t for the individual. The individual is meant to serve the practice. And that dovetails strangely with branding. That’s what I hear in your friend’s comment: “That’s not why people come to this studio.” That’s not the image we project. If I change the rules, I’d be going off-message and outside of the expected exchange mechanism. So there’s this really fascinating way in which a patriarchal rigidity inherited from a few teachers, has melded itself seamlessly into capitalist branding structures, in which the thing that’s on offer really can’t be questioned. But it’s weird, because even Apple takes feedback on its iPhones. Many yoga studios feature a kind of capitalist branding that isn’t responsive. One of the supposed rules is: “Find out what the client wants.” When you ask the question, “How would you know whether your students really want a change?” – you’re really pointing to the difference between authoritarian and customer service models.

Mike: Perhaps the difference is between gym culture (lots of people want a work out, nothing wrong with that) and what I think of as post-yoga. The post-yogis are mostly women yoga teachers who have done endless workshops, trainings, self practice. Nearly every one has been injured through over practice, repetitive strain, sometimes too much flexibility. Some of the studios, I think, are trying to hold both sides of that divide, but the inclination is always to promote the more aggressive space, the hot flow workout hour.

Matthew: Talking about gender brings something to mind. The friends you reference are women, and most of the yoga people I know are women. So the vast majority of injuries that I’m aware of are sustained by women. Given the fact that there’s an inherited patriarchal teaching structure, I’m hearing Žižek in my head and thinking that just as capitalism requires flexible workers, so patriarchy requires flexible women.

Mike: At the end of a ten-day vipassana retreat I asked one of the fearless leaders: “Do people ever leave? Does everyone always stick with the entire ten-day program?” He assured me, “Only the men leave. Women already understand pain.” I couldn’t help but be struck by the incredible diversity of people who showed up. But while the retreat is extremely painful, women never bow out, it’s only the men who can’t stand it. I wonder about that in the context of a yoga culture that sets pain up as an implicit marker of progress.

Matthew: It sounds like you had a painful experience while sitting on that vipassana retreat. Did you have some kind of critical moment in which the pain or the perception of the pain shifted?

Mike: It happened every day. You’re doing one-hour sits for fourteen hours a day, so you’re in full-on pain from the start. I just spoke with my friend Marina who said that she had to do physiotherapy on her knee for six months afterwards. Though she hastened to assure me that the retreat was five-star and that she wouldn’t want to change a thing about it. On retreat, the pain comes and it feels like it’s coming for a long time, because your new full-time job is noticing sensations. After awhile even the deepest sensations of pain change. The reaction shot shifts as the impossible becomes manageable. By day four or five you’re settling in, the internal tweeting is down to a whisper, and you can observe the sensation patterns arise and pass away with something like curiosity.

Matthew: I’m asking about the breakthrough moment in vipassana because I think there’s a folklore crossover between how intense or painful experiences of meditation and asana are told. We have a threshold, and we have a breakthrough. I know that in sports medicine terms, the mechanism of endorphin release at a certain intensity of pain facilitates a flight-response advantage. It will allow the marathoner to finish a race on a broken tibia, or the football player to not realize that his shoulder is dislocated until the end of a scoring drive. So I’ve wondered whether the nervous system is forced to make a different choice after ten days of sitting or lots of intense asana. I wonder if we have to release some kind of analgesic chemistry in order to survive these spiritual practices. With the retreat stories, I’ve heard over and over again that a person is in their bed on day seven, quivering with pain, and then they say, “Okay, one more sit. I’m going to do the damn sitting, and then I was flooded with bliss that day.”

Mike: Pain is the doorway, no question. If you don’t go through it, there’s nothing on the other side. One of the aims of vipassana practice is to stop the sitter from identifying with sensations. That’s my itch. That’s my hunger. And what sensations could be more urgent and compelling than pain? If you can stop labeling those sensations as “my pain” then your body has realized what Stephen Batchelor calls the principal of the dharma. That everything arises and passes out of conditions. During the retreat this is not an idea, it’s something you experience in your whole body, moment after moment. To enact the separation of paying attention and not identifying is both a movement towards and away from the body. Amazing things happen. I had a flashback of my first body memory. I was back inside my mother, feeling her breathing, the blood red of her organ life, and then the involuntary contractions when she started to smoke. It emerged from every part of the body, and was so complete it felt like time travel.

Today I have a couple of major reservations. The first is about your object of inquiry. Why does it have to be so physically painful? Do we have to sit so long that people need to undertake physiotherapy for months afterwards? And the second question is even more fundamental. Do the insights gained on the cushion make us better people? Sitting is not a relational practice, who cares if you can concentrate like a demon for months on end if you can’t show up for your friends? I think we can all rattle off the stories about great dharma leaders who had major sidelines in greed, sexual exploitation, dishonesty. On retreat, as the hours roll past and various people begin to cry or glow in the dark, it can create a feeling that everyone’s having their own trip. Trust the form. It’s all going to be okay. How we love to ring out the special experiences that make us feel so special. Like the silverware reserved for guests.

Matthew: It’s a strange combination of “This is a universal form — whatever it is — but you’re on your own. It’s applicable to everyone, but you will have an irreducible and incommunicable experience of it.” It affects kind of a cosmic shrug. “What should we say about our pain? Well, we’re not sure. It will pass.”

Mike: The tape-recorded leader of the retreat is S.N. Goenka, who was drawn to the practice because of migraine pain. On my last retreat there were two chronic migraine sufferers, both of whom recounted the same miraculous breakthrough that the founding father had arrived at decades earlier. Incredibly, they had both failed to bring enough medication. The migraines were coming on and there was no way to stop them. Both were advised, separately of course, to simply “Do one more sit.” And then one more. And then one more. They begged the organizers, “You don’t understand — I’m going to die from this pain, it’s not humanly possible to withstand it.” They both described an overwhelming crescendo of pain, and then in a single instant that they could both identify, they burst through to a clearing on “the other side” and sat pain-free for the first time in their lives. Both were men, one in his twenties, the other well over sixty.

Matthew: Have you been in touch with either of them since? I’m wondering what the longevity was of that recovery.

Mike: I wonder too. It’s certainly an inducement to practice.

Matthew: It is, but having heard many such miracle stories myself, I’m also aware of how they frame the rest of the narrative surrounding practice. They’re presented as though they are evidentiary. And they are, in a self-reporting sense. But they’re only anecdotes: “I heard that vipassana cured so-and-so’s migraines.” That narrative has power with regard to encouraging people to exert themselves in a particular way, to validate the method. It’s a great story, but I’m very aware that we don’t know how it ends.

Matthew: I think it’s good to see these as cautionary tales, that striving and sitting through pain can be reframed in terms of someone who’s willing to inflict an incredible amount of suffering on themselves, and then is willing to project a need for that suffering onto others. That projection can be named after whatever ideal is floating through the room. So how has your own experience of pain and injury in asana changed?

Mike: I sustained a rotator cuff injury two years ago. It happened via a couple of different yoga classes. One was a slow-motion Ashtanga practice and the other was an Iyengar class that was offered in the neighbourhood. I met the instructor in the elevator who assured me, “I know exactly what to do about your shoulder.” She never touched the joint, or had me demonstrate its motion range, and I’d made it clear to her that I was already injured and resting, trying to recover. “Come with me,” she said. So I go down to the class which is now rejigged with a special series of poses dedicated to strengthening the muscles around the rotator cuff. As we proceed, and I am adjusted in every single position, I rip the joint apart, and for the next few weeks I can’t even lift my arm up in the air. Of course I was foolish to follow my teacher’s advice, but I had been in pain in this same class many times before and it had turned out to be OK. Why was this pain permanently damaging, while the other pain was alright? I simply don’t have the know-how to tell the difference. I’m not sure what the muscle is that could tell the difference, but the one I have is obviously undeveloped.

I spent a year rehabbing with a rubber strap and slowly the rotator cuff got better. Though it will never be the shoulder it was. And I have developed a wariness around yoga that has kept me from the mat. I remember reading about Krishnamacharya, the great modernist yoga collage artist/teacher, who offered everyone their own practice. This series of poses would evolve (and continue to evolve) after watching the individual student, and working with them, and adjusting them. In other words, the practice of yoga was relational. Doesn’t this make sense? But perhaps there’s no time for that in studio culture. Perhaps everyone would go broke if it all came down to one on one.

The teacher I see now is Patricia White at Yogaspace, who works out of a woman’s lineage that begins with Vanda Scaravelli. It’s anti-hero yoga: a lot of the poses don’t look like anything at all. You’ll never see them on the cover of Yoga Journal. But there’s a form underneath the form. The work isn’t athletic or aerobic, and there’s not so many standing postures these days. I feel like she’s breaking down the most basic postures of walking, sitting, and lying down and showing my body how to receive these basic asanas.

Matthew: So you began with an acceptance that pain was part of the process. But it seems that with the shoulder injury that really dissolved. In between those two positions, what was that edge of pain telling you in practice? How was it expressing growth or limitation?

Mike: Michael Stone kindly invited me to his month-long retreat a few summers ago even though I didn’t have the cashola. Michael is a genius yoga teacher, endlessly inventive, always coming up with a fresh take, another approach. But he is also a rare and splendid physical specimen, and like most of those on retreat, he is decades younger than I am. As a result, I staggered from the exit door each day with every part of me hurting. Mornings began with a sit, during which a woman in the corner would sob for the entire half hour. On day three someone dozed off and planted their face on the floor and had to be taken to hospital. On day four during lunch break someone got their bike wheels caught on a streetcar track and broke their leg. Have you ever watched forty people have a slow motion nervous breakdown? The focus throughout was on the end of the exhale, can you stay there and feel the unwanted parts of your body/mind as they settle into the darkness layered into the mula bhanda, and can you bring those difficult and left behind feelings up with every breath and let them pulse through your heart? It felt like a dismantling of body and self. Our aching bodies were the lens through which we experienced the philosophy and the chanting and the Zen that was being unpacked. Together we stepped off the edge so we could find that place where the bodies we used to have, and the stories that we told about that thing we called the self, no longer held. What was harder to find was the relational piece. How do we put all of the bits together again? We had shared the ecstasies of falling apart but lacked the recipe to put Humpty back together. When a teacher shines so brightly at the front of the room, they invariably cast shadows, and some of those shadows are sangha. Who are we when mom and dad leave the house? What lay shimmering through the broken fog was the promise of practice. Just keep practicing. Though I have to emphasize that as Bernie Glassman says, “It’s just my opinion.”

Matthew: It goes back to your earlier question: “Is there another way to do this work?” Because what you’re describing is that the process of self-making and the process of presumed bodily integrity are intertwined, and that especially as the body becomes more “open,” more expressive of lengthening, stretching, unknotting itself, the personal self, which is seen as a series of contractions, is unravelled. Obviously there’s psychological pain in learning that you’re not who you thought you were, or that you don’t have to be who you thought you were, or who you were told you were. The physical pain involved in stretching or mobilizing a joint is analogous. It leaves me with the question of whether pain is instrumental, and if there is something else available?

Mike: I think there’s another way to do this work. Just as yoga teachers are often encouraged to promote an endless athletic cheer, it’s also possible for them to project the post-injury body, the imperfect and broken body. This is what is happening in Christi-an’s classes where her inclusive speaking about trans bodies, differently-abled and shaped bodies, the consent cards she’s developed around being adjusted or not (touch me, don’t touch me), and a physical practice that is no longer aimed at the pose but at the places between the poses, all this is a projection or sharing of some of the most difficult places in her life. But will her combination of ethics and physical practice be enough to withstand the relentless capitalist tide that has turned yoga into just another business?

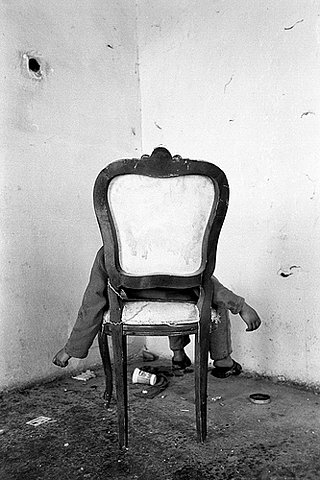

Patricia White just got back from a hip replacement, which she insists came from her long ago days as a dancer, and not from yoga. On Wednesday mornings, she steps into the room on a cane, a striking image in a yoga studio. Who do we put at the front of the room? An older woman walking on a cane. In her class I am beginning to feel tiny openings in the hip flexors and around the collarbones that I’ve never felt before. I can follow this network of fissures and they lead me to new places where I can say yes. It’s like the life you share with your best friends. As they tell you the story of the past weekend, even though the circumstances are new so much of the telling is familiar, you’ve been hearing variations on this story for thirty years. Those small variations are at the heart of what friendship is. How to love these small differences? What Patricia is teaching me is how to get in touch with and love the small changes. It doesn’t look like much from the outside. When I started studying with her I would look around the room and think that people were just hanging out. That they weren’t trying hard. It’s taken many years for me to understand what the judgmentalism of “trying hard” might really mean. Perhaps it’s about accepting a very different notion of what “work” is. One of the unfortunate congruencies between yoga culture and capitalism is the notion of work. In the Fordist economy there was work time and holidays. In what some are describing as the New Economy, work time never stops, while our digital devices ensure that every place is potentially a work place. In yoga there is another way of saying this: “Practice. Practice. Practice.”

Matthew: “Lean in.”

Mike: Yeah. “I’ve gotta work it till I find my edge.” That’s what the whole machine of dominant culture is urging us to get on with. Even as yoga continues to explore and celebrate resistances both in and outside the body.