Originally published in: Curtocircuito Festival Catalogue, October 2014

Positive is a double-edged sword in the cinema of Mike Hoolboom. On the one hand, when the Toronto-born filmmaker was diagnosed with HIV amidst the confusion, ignorance and prejudice that pervaded the AIDS epidemic in the late 1980s, to be labelled ´positive´ was to be living under something resembling a death sentence. On the other hand — as is so amply demonstrated in Hoolboom´s own 1996 short Letters From Home — in the decade following the AIDS crisis, positivity in the emotional sense was less an individual attitude than a survival mechanism for an entire community struggling against social misconceptions and institutional failures.

Filmmaking has been a thing of affirmative action for Hoolboom. In the decades since his diagnosis, he´s amassed a body of work comprising more than fifty films of varying lengths. In addition the Canadian has been known to revisit and revise such works — trimming, lengthening and merging them as well as withdrawing them completely from circulation. Hoolboom´s cinema is one of ongoing re-evaluation and self-definition — an observation perhaps applicable to any prolifically self-observing artist, though in this instance things appear to be especially sharpened. Indeed, Hoolboom`s tireless, creative energy pervades each individual work — his films are aesthetically maximalist, tonally composite, emotionally complex and thematically dense.

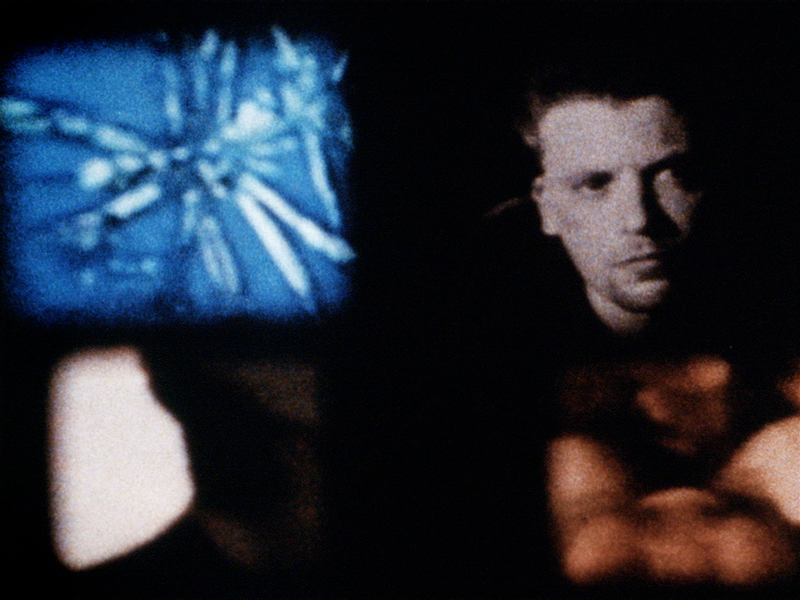

Hoolboom´s oeuvre is both historically and culturally specific. His award-winning 1993 short Frank´s Cock is as good an example as any of how inescapably of their time his films are. References to MTV and to iconic, era-defining sports stars (¨the Michael Jordan of sex, ¨the Wayne Gretzky of hard-ons¨) place this eight-minute short thoroughly and aggressively in relation to a contemporary pop scene — a zeitgeist from which it is also at an appreciable remove. Hoolboom heightens this disconnect through avant-garde techniques: multiple frames compete for our attention within his overall composition, while actor Callum Rennie addresses viewers directly in a single-take monologue to camera. If stylistically it´s plausible to imagine this as part of early-90s cable television, in terms of content it´s decidedly less so.

The films respond to their maker´s bodily afflictions in other ways. Hoolboom´s hand-processed works are the product of a physical process involving an intimate care and attention far removed from a depersonalized industrial practice, whereas the ways in which he alters found footage and melds it with his and others´ home movies speak of permanent distortion, a transmutation whereby the new offspring is at once recognisable and eerily displaced — changed forever, and yet the same. Meanwhile, hand-written intertitles and voice-overs-such as those in Buffalo Death Mask (2013) bring a verbal urgency to proceedings. As part of a community much maligned and repeatedly silenced, it is not enough to merely exist — not enough to think, therefore be — the old adage demands a reformulation: I speak, therefore I am.

When such a community´s daily experience is one of fear, misunderstanding and contempt, speaking out and the optimism that entails are themselves sources of vulnerability. Such themes come to the fore in Hoolboom´s remarkably beautiful feature-length essay film Tom (2002) about New York cineaste and filmmaker Tom Chomont. Himself diagnosed with HIV, Chomont recounts his own life with empowering frankness, while Hoolboom situates his story within a wider, cinematic history. The film is an impressive amalgamation of movies from the previous century which it juxtaposes against the unthinkably personal heartache and ongoing preoccupations of its subject as the latter heads towards an uncertain future.

Indeed, in looking both forward and back within the eternal present tense of the moving image, Hoolboom has in recent years touched upon another tension — that between analog and digital forms. Though it´s celluloid whose death agony cinephiles have begun to decry, Hoolboom can´t afford nostalgia: in Tom the piling on of images both digital and analog suggests at the very least a curiosity for change — and all the uncertainty, vulnerability, fear, discovery and wonderment that come with it.