Originally published on MUBI website.

Is being photographed the only way to cheat death? Ask Mike Hoolboom, in whose Public Lighting (2004) the question is posed. Presented on 8 October as part of a retrospective of his work at the eleventh CurtoCircuíto—the excellent international short film festival in Santiago de Compostela, a city in Galicia, northwest Spain—Public Lighting is in many ways emblematic of Hoolboom’s work.

To begin with, there’s its agitated, almost frantic need to pay tribute to the world and its miscellany—and to allow such heterogeneity to inform its imagistic, editorial and thematic fabrics. Separated into seven aesthetically distinct segments, Public Lighting is about the many sources of pleasure to be found in an otherwise uncertain universe. It is about Madonna, Philip Glass, New York; it’s about identity and the inevitability of change; it’s about the amusing and tragic disconnect between unspoken desire and lived experience. More than anything, however, the film is about images: not just the literal, pre-existing and original footages that Hoolboom lays atop one another, but those ethereally conjured by association—with a mysterious glance, an erotic juxtaposition, a delicate superimposition or a musical cue.

The Toronto-born filmmaker’s oeuvre is an ongoing project whose individual components burn with a desire both to confront and to break free of the social prejudices, political failures and personal torments surrounding his own continuing battle with HIV since the late 1980s. Hoolboom’s is a gestural cinema: essayistic, yes, but also profoundly political. The singular sense of self that permeates his works is conditioned and conditioning.

“Each of us,” he noted in a post-screening discussion at CurtoCircuíto, “if we live past a certain moment—let’s say 5 or 6 years old—have so many faces within us. We have enormous pressures, from the outside and then from the inside, which creates one image of who a person might be. The austerity program being imposed in this country, for instance, is an image of how a person might be.” Adversity, then—whether economic, political or indeed biological—informs but never defines identity, precisely because a person is always, ineluctably and irrevocably, fighting back.

Hoolboom’s films—from Frank’s Cock (1993) to Buffalo Death Mask (2013)—are exhaustingly maximalist in the best possible way. In Public Lighting, a line of text referring to Philip Glass reads, “It’s not the melody people listen to, but its persistence.” The same, indeed, can be said of Mike Hoolboom’s cinema: it’s perhaps not the images we see, but their perseverance. The following interview took place on 9 October in dry but visible proximity to the cheerless downpour of a Galician autumn.

Michael Pattison: This is a new version of Public Lighting. What’s changed?

Mike Hoolboom: I had a retrospective at the Anthology Film Archives in New York. I showed Public Lighting from a Beta SP master that looked suboptimal because the projector settings wanted to be fed with digital happiness. It made me wonder what the movie could look like as a high resolution digital file.

Has it changed narratively?

No, though I recreated the Madonna and Philip Glass chapters. And I tweaked all the other sections, but now I’m really wondering if that’s a good idea.

The work in progress that’s screening here—the synopsis only says it’s a mystery, a surprise. Tell me more about it.

It’s called Scrapbook. It was shot in 1967 by my friend Jeffrey Paull, who was working in what’s called a development centre, which is a combination mental hospital and residential daycare. The centre began at a moment when media education was just beginning in North America, and it carried utopian hopes. Jeffrey was brought in to teach the kids—all of whom had various psychological problems—how to make pictures, which meant analogue photographs, darkroom processing and printing, video introductions. These gestures were considered therapeutic, although he wasn’t schooled as a therapist. But the act of producing pictures of each other could address fundamental questions of identity formation. How can you be part of me and separate from me at the same time?

And this is a work in progress?

Yes.

To what extent are all of your films works in progress?

Everything gets worked on until I can’t stand it anymore, and then I withdraw it. It’s nice to have a body of work that shrinks as you grow older. I’m aspiring to that less and less.

Your films are so densely packed to begin with. How do you begin to script a film like Public Lighting?

Often it begins with a conversation that asks for the company of pictures. The final chapter in Public Lighting is called Amy, and it began with a long chitchat with a woman who was photographed by Jock Sturges when she was a teenager. She talked about what it felt like to have a pictorial record of his looking at her; what appeared like a portrait of herself offered a version she’d never imagined before. It became increasingly difficult for her to keep the picture someone else had made outside of her from taking up residence inside of her. How do I learn to see myself, if not through the looks of others?

Presumably there’s a level of intimacy required before you get onto these topics in everyday conversation. Were you already friends with this woman?

Like all of the most important moments in my life, it arrived out of a chance encounter. We didn’t really know each other.

How do you come to source the imagery that you employ in your films?

Sometimes I meet someone who is “camera ready.” When we meet, they are already a close-up. On the other hand, some movies require pictures that are made by others. In the portrait of Philip Glass for instance, I wanted to create a visual analog for his music, which is all ground and no figure. What is Philip’s ground? The city of Manhattan. I divvied up the island into moments, and assigned each a text stanza and musical motif.

What drew you to Philip Glass to begin with?

Pleasure is always the compass. I have been haunted by the fantasy that there are two kinds of artists. The first paints their canvas in a single gesture, in an instant. The second has to invent their paints, and then use every colour, and then the colours that haven’t been invented yet. Everything that’s ever happened to them has to be collected and stuffed inside the frame. I’m condemned to being the second kind of artist, but long to be the first, like Mr. Glass.

You’ve returned to New York City several times in your work. What is it about that place in cinematic terms that you find so alluring?

When I hear the words “New York” I conjure the island of Manhattan. Geography is limited and expensive, in order for new buildings or new hopes to appear, something has to be torn down. Manhattan is the physical expression of a double movement: every inhale requires an exhale, every holding on demands a letting go and release. In this sense, the city becomes a metaphor for the self, or even how one might make a biography. What is it that can’t be shown, what will be left out of the frame, what can we bring forward as evidence? The self as archaeological dig: this was the beginnings of my attempts to make a movie about my friend Tom Chomont.

How important is it for you to finish one film before you begin another?

Monogamy used to be a rule. But over the last four years I’ve encountered one obstacle after another, and each stoppage occasioned a new project. As a result, I have a large and growing backlog.

You collaborated frequently with editor Mark Karbusicky [1972-2007]. What did Mark bring to your films?

It may be strange to talk about material concerns in the phantom paradise of digital media, but the computer is also a machine that touches back. It was Mark’s fingers that played the keys for half a dozen years with me. We made four feature length movies and a brace of shorts, most of them portraits. In each of these works there is a subteranean rhythm, a pulse, that speaks of the moment of contact between two people. When you meet someone there is a feeling tone that runs between the two of you, and Mark’s genius was that he was able to materialize that tone, the secret life that we are sharing, even as it seems we are talking about the weather again.

You’ve worked in the past with analogue film, and have hand-processed 16mm. Is digital something to embrace, something to fear or both?

Today’s movie avant-garde cherishes its silvery fetish of film as film. When I began making moving pictures emulsions and hand-wound cameras were the norm. We had four labs dedicated to super-8 film alone, so it’s hard for me to muster the same sense of loss or nostalgia. I think the entire project of fringe cinema might be summed up in a single word: attention. And within the project of attention there are two broad categories of work, with much inevitable overlap. The first narrates materials and processes, and the second has to do with identity politics. The film nostalgists are firmly in the materials and processes camp, they are often interested in horizontal structures, privileging the act of looking, sometimes suspicious of language, they unpack the tools of the trade. The medium is the message. Not incidentally the artists and curators who support them are mostly white and male. The second camp or sub-genre narrates the conditions of a specific identity or identities. Formal manoeverings are pressed into the service of alternative messagings. New forms for new lives.

How important is it for your films to be shown and exhibited in cinemas?

Without an audience the work feels incomplete, and the enterprise is haunted by futility. Are we speaking to someone? What I’ve been struggling with at this late moment in my life is a crisis of faith. When I started making work I understood that my difficult, obscure, materialist movies were part of a larger liberationist project that included gay liberation, black liberation, women’s liberation, animal liberation, and anti-colonial movements. The perhaps ridiculous assumption was that if one could look closely enough at the materials of cinema, one could find within them encoded the mechanisms of capitalism itself. We would disarm capitalism by exposing the operations, and we would do that by creating different models of attention, which was what fringe cinema was busy producing. Each small movie created a different model of attention. Through sometimes heroic acts of duration, we would practice different modes of consciousness together in the cinema, and these would be sites of resistance, they became models for how we might live collectively outside of capitalism.

And that’s changed?

The political project has been replaced by a new professionalism. There are careers at stake, tenure files that need to be padded, and at this moment of media overflow, a new cadre of curators willing to wade through the murk and tell us what is important. I began working as part of an avant-geek movie collective in Toronto called the Funnel. Equipment was rare and expensive so resources were shared. Today those machines and labs have been shrunk into microchips, which has brought us new forms of loneliness. In place of the collective loneliness of the movie theatre, the new loneliness of the internet, where I can be kingpin and publisher of my own empire, which is everywhere and nowhere. The project of attention is still operative, and the technocrats have even found a way to measure it, attention registers as hits. The more times you are hit, the better off you are.

It seems to me that the avant-garde’s been individualized in a way that perhaps wasn’t in its origins and intentions.

There was a curious duality at work. We scrummed in the cinemas in order to celebrate a hyperbolic subjectivity. The old group think was that everyone needed to nod in time. But we would form a new kind of togetherness by celebrating each person’s eccentricity. The only way we can come together is by insisting on the singularity of each part of the group. Fringe audiences were like jazz bands, everyone played their own riffs, but together it sounded like music.

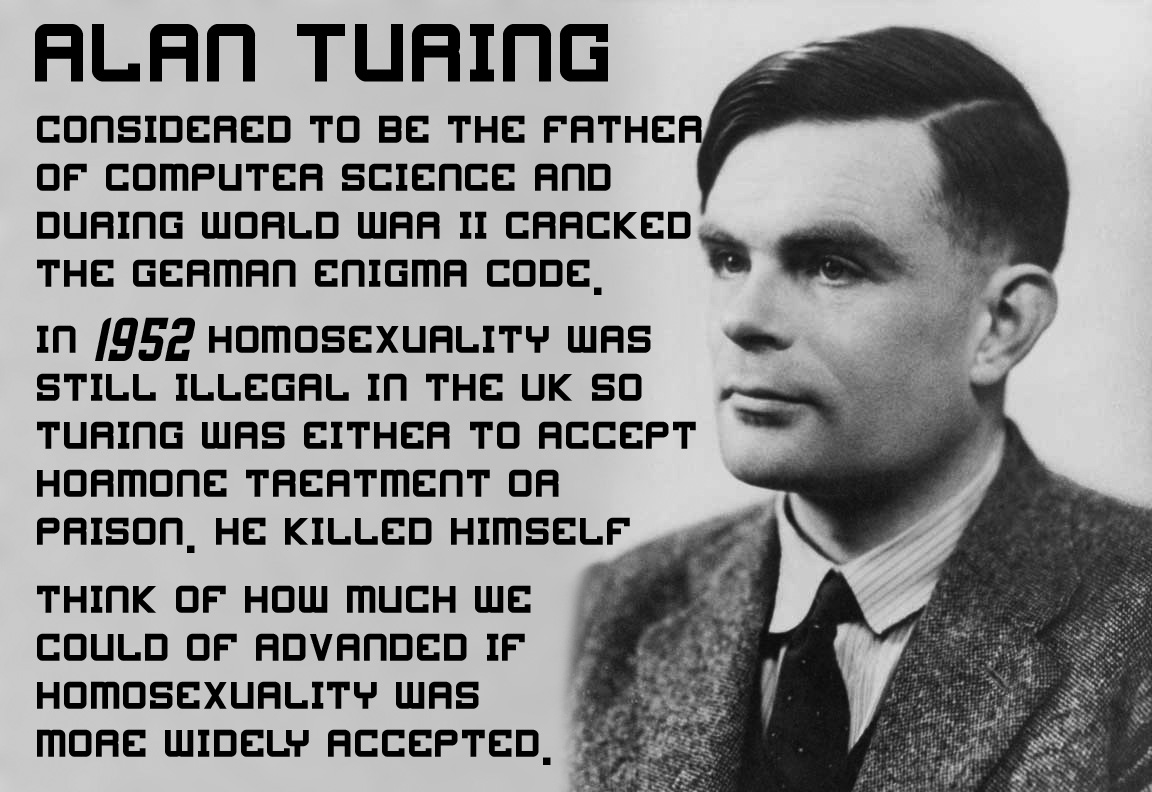

Within these singular expressions, where each movie was as unique as a fingerprint, one could also find deep strains of queer counterculture. They wouldn’t have been named like that at the time, but today the work of Kenneth Anger can be understood as part of a larger liberationist project. It’s the work of one person, but its also part of a movement that has reduced gay bashing and allowed people to live more ordinary lives, instead of having their secret hopes drowned in estrogen injections.

How comfortable are you to be termed and exhibited as an experimental filmmaker?

I wonder if it raises the pulse of unknown audiences. Do I want to hear an experimental talker, would I like to date an experimental kisser? It makes the project feel tentative and difficult. It sounds like a tough night out. I prefer the term fringe because so much circulates on the fringe: iconoclasts, moods, minor literatures, theatre.

To what extent do you find programs explicitly dedicated to experimental cinema problematic?

I think they’re helpful in identifying a field that to people remains completely opaque. One of the great joys of being a movie maker is that everyone has some kind of stake in movies, they’re parts of people’s lives in ways that, for instance, concrete poetry or ballet might not be. But it also means that people have very particular ideas about what a movie should be. You call that a movie? The difficulty with experimentalisms is that we can create ghettos for likeminded specialists. I think the hope for these fringe orphans, if they might gain some kind of political purchase, is to be able to circulate them beyond the usual suspects, beyond the thirty or fourty hard core attendees of all things avant-garde. Beyond the professionals who are running festivals or distributing difficult media work. It’s great those folks are in the ring, but it can’t only be for them. This is what we see happening this week at CurtoCircuíto and the results are so very gratifying.

Your question raises another uneasy suggestion. Has the avant-garde become a genre? And why not turn to Lauren Berlant’s excellent definition of genre as “a zone of expectations about the narrative shape an experience will take.” How could you create a genre of works that are supposed to be singular when the avant demands a new genre for each and every movie.? The fact that works can be tagged and collected in programs suggests that a certain project has ended, though of course there are resistances.

What films do you currently respond to? Is there anyone whose works you find particularly exciting?

I fall in love every day. But for the past three decades my life and work have been in deep conversation with Steve Sanguedolce and Gary Popovich. Gary’s about to show his first new film in fourteen years. It’s called Souvenir and it’s been a slow burn. It shows the history of everything, from before the big bang to our post-future. I can see every relationship he’s ever had, his kids, all of his living is in this film, and it makes me wish that I had the patience to persevere in such an elegant fashion.

Your 2002 feature, Tom, is about your friend Tom Chomont [1942-2010]. Tom’s billed in the film’s synopsis as a raconteur. How important is it for you to tell stories, to record certain phenomena and experiences through storytelling?

Stories help connect us and are such helpful memory devices. The cinema is an empathy machine. It allows us to jump into other people’s bodies and feel their experiences. One of the most important things it can do is to take us into dark and unimaginable places which we are invited to inhabit with a new sympathy or even tenderness. The hope of course is that we might be able to treat our own darkness in this way, and then the unseen faces of our own neighbourhoods and cities.

When I started work on the movie with Tom he was in such terrible physical shape. He suffered from Parkinson’s, which is an illness that causes one to shake uncontrollably or freeze up in paralysis. The way he looked was so different from the feeling tone we produced. So I needed to find a workaround: how can I show people the Tom that I am feeling and seeing? I couldn’t simply sit my friend in front of a camera and cry, “Action.” What the movie records is my attempt to cross the room and find his face. It takes a long detour in order to cross the room, like the four steps that Maya Deren makes in Meshes from the Afternoon, where her sandals cross the whole world in order to find herself.

Tom made many films and videos, and there’s very few words in them. He’s part of a ‘visionary,’ eye-first, new American cinema, which comes out of a fundamental distrust of language. It’s as if language has failed us so now we need to return to the more primal sense of seeing.

Do you think language has failed us?

My work is stuffed with language, I am describing Tom’s conditions, which became a sort of inheritance. But while his work was often silent, Tom himself is a prodigious speaker. He has a photographic memory, he startled me more than once with his ability to bring back the first meal we had together, what I was wearing, even the conditions of his birth. Oh yes, his first memory. He’s on the delivery table surrounded by white light which dissolves into what he later comes to recognize as human forms: a doctor, a nurse, finally the breast of his mother. It all came back to him during an acid flashback.

You make reference to cinema as an empathy machine. I’m interested in the tonal complexity of your works. On the one hand they’re incredibly funny, and in the same moment they can be heartbreakingly sad. How do you approach and achieve that?

I made Frank’s Cock in 1993. It would be three years before the cocktail arrived to save the lives of everyone who was fortunate to be born in a country that has reasonable healthcare. Though we didn’t know that then. HIV was an inescapable death sentence, and thousands of us die everyday. Well, of course thousands are still dying every day, but then there were no options, not even for the privileged. There was a lot of fear, doctors would be afraid to see you, nurses wouldn’t even walk into your hospital room. How did Leonard Cohen put it? It put a dent in my mood.

I wanted to make a movie “about” AIDS without reducing a person to their symptoms. I had a number of very intense encounters at the fledgling Persons With AIDS organization in Vancouver, and I wanted to bring others into the room. I wanted to conjure a subject who would be charming and funny, as so many of the brothers were, and then after awhile you find out they have AIDS. The movie extends an invitation to jump into this person and live a moment of their life, and feel that you might also have a stake in this thing called AIDS. Hence the balance of humor and sadness. Humor is a good way to open the door.

Not enough films do it. Especially within the avant-garde.

Many of the humorous works, even from the canonical avant-garde, would never be shown today, or at least not in fringe movie fests. Those early movies by the Kuchar brothers? Even Jack Smith’s work. I think they would be dismissed as trash. Not in our festival please, we’re all about serious.

I want to talk about ‘Hiro,’ the sixth (of seven) chapter in Public Lighting. You’ve mentioned this is giving expression to memories that someone doesn’t necessarily have, as an immigrant. Could you elaborate on that?

The movie features a Japanese-Canadian actor named Hiro Kanagawa. His first name is already a short form for the city of Hiroshima, which was the first city destroyed by an atomic bomb. His most important memories are ones he’s never had. He’s haunted by the bombing, though he didn’t experience it himself. He feels he is living in the aftermath, as a survivor, where some kind of genetic trace or obsession calls him back.

My parents’ extreme experiences during the Second World War continue to mark me. Their memories are deeper than anything I experienced in the cloistered suburban compact that they tried to wrap themselves around. Their efforts to assimilate into a new culture were so rigorous that these buried memories were nowhere and everywhere. Many children of immigrants I’ve spoken with have similar kinds of experiences, our inheritance is the undigested trauma that has occasioned a displacement that never quite ended. Where are we? What kind of place is this, that continues to conjure the place that has been left behind?

They were both born in Indonesia, then named the Dutch East Indies. My mother endured the Japanese occupation and the camps, while my father arrived in Holland shortly before the German invasion. His father was dispatched to Buchenwald, taken away from his home by black clad German soldiers if you can imagine, a scene my father witnessed when he was ten years old. Let’s stop for a moment and wave our emotional life good-bye.

Years later after they emigrated to Canada, the family embraced a form of double vision. There was the searing psychic reality of these experiences, and then there were the rows of orderly houses in the neighbourhood, the school’s regulation of hours, the empty streets. Out of this double vision arose something like experimentalist movies which are forever questioning the most fundamental acts of representation. The way we make pictures.

If you had to choose a work to summarize your aesthetic, or if someone could only watch one film to get the best idea of your work, what would it be?

The one that I’m making now.

Scrapbook?

No, it’s called We Make Couples. Most of it is shot in super-8, I’m working on version four right now. It’s a portrait of two women who create a delirium of good feeling whenever they are together. They are having a conversation about relationships and capitalism that embraces Occupy Toronto. How can we create a couple that isn’t simply going to bury itself in domesticity and support the old reliable repressions? How could a couple be an agent of social transformation?

And how can they?

Still working on that.