Originally published in Transit (in Spanish!) http://cinentransit.com/encuentro-con-mike-hoolboom/ and Lola (in English) http://www.lolajournal.com/5/hoolboom.html. Extended gratitudes for the heroic translation efforts of Cristina to make it possible.

Cristina Álvarez: The three retrospective programs at the Curtocircuíto festival offered a very small percentage of your total film work to date. How was the selection arrived at?

Mike Hoolboom: The retro is a cocktail of old and new, though I’ve developed the unfortunate habit of returning to already finished movies and giving them a polish. Even the finished is unfinished. The feature-length Public Lighting (2004), for instance, was remodeled just a few weeks before the festival (digital media means last minute adjustments can happen right up until the curtain rises, in the future directors will be cutting while the screening goes on, just a few frames ahead of their audience). I had made another feature-length bio doc about my friend Tom Chomont, but after a few years a more reasonable view arrived and I cropped twenty-five minutes out of it. The movies get tighter and shorter as they grow older, until one day they disappear entirely. Most of the work has been thrown away, the parking garage in my apartment building hosts an impressive trash receptacle, and much winds up there. Video masters, film prints and negatives, a great purging relief is just an elevator ride away.

Adrian Martin: We read that on your Wikipedia page and didn’t know whether or not to believe it. Why do you do this?

Mike: We live in a culture of too-muchness. The old sixties dream that everyone would become both an artist and an international broadcaster has been realized in many parts of the world, and the result is a tremendous crush of work. Even here at the Curtocircuíto Fest, the programming team watched 3500 official submissions in the past year, it’s madness. I am trying to help relieve the traffic jam by culling some old riffs that are no longer helpful.

Some movies belong to the contact moment of their premiere, which is often local, in front of an audience of familiars. The work of the movie is met by the work of the audience, both sides create a rare visibility, like a match struck in the darkness.

Other movies may split its life between a pair of cities, as if every audience member had a twin. While other movies, even more rarely, may survive the year of their making, they may even lumber on for four or five more years before appearing quite without use to its future citizens. Of course it’s supposed to last forever, but most work has an expiry date attached. Some movies, perhaps the most important ones, expire before they are ever seen.

Adrian: Do you keep at least some pieces of the film to re-use?

Mike: It was easier to regather the body parts when I worked in 16mm for two decades. Today video formats seem to go in and out of favour as quickly as technicians can raise the flag. There must be social engineers in Tokyo for whom everything we know today is already part of a distant obsolescence.

Making movies means being committed to a project of reviewing an archive. The archive may consist of a single shot, but that single shot is poured over, examined from every angle and mood and temperament, and often these reviews provoke dissatisfactions, there may be too little of something or else too much. Sometimes the solution is instantly apparent, but more often it leads to a productive state of frustration. I vote for the once-child psychologist Adam Phillips who insists that frustration is the place where creativity begins.

Adrian: In your Masterclass lecture at Curtocircuíto, you spoke about attention – paying close attention to people – and your concept of a cinema of attention. Yet, at the same time, the montage of images and sounds in your films is like an avalanche of free association. How do you square the idea of attention with this aesthetic of distraction?

Mike: The classical avant-garde approach to the question of attention is to look at a single thing for a long time. I’m thinking about the swimming pool in Ellie Epp’s Trapline (1976) for instance – 12 shots, a single pool – or Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967), shot in a single room over the course of a few days. I would love to make those kinds of movies but I wouldn’t know how, so I approach the question of attention from the other side.

Traditional movies convene audiences in order to create a communal response, we come together not only to see the same thing, but to see it in the same way. The corporate movie experience sutures together different people as if we were parts of a single body. The fringe artist has different hopes. The ideology of the fringe insists that only when we come together, can we figure out who we are as individuals. When we express our individuality, when we are able to locate our signature, our singularity, only then can we produce a chorus of voices, a collective.

This is what lends urgency to an individual voice, because it’s only by finding our own voice that we can produce the collective. Jazz bands work like this, at least occasionally. The structure is horizontal, and produces an embodied image of democracy. By “embodied image” I mean that fringe audiences become (at least sometimes) a picture of possible states, a utopian view, but also that we are that state, as the movie passes through us.

How could you promote this kind of gathering as an artist? Perhaps by offering not a single-pointed exclamation mark of attention, but a field of vision. Within this field there might be signposts and markers — to save it from feeling like the vomitorium — that help each viewer find their own way through the movie. The hope is that each audience member could gift themselves moments of reflection (decisive moments) about how they’re putting the movie together. Why am I choosing to remember this picture? Why are those sentences lingering over that sound? It’s like looking back on a snowy field and seeing your own footsteps. How did I get here? In this way both the content and the form become visible, but neither exists before the viewer is there to activate them. Either you make the crossing or you don’t. And of course there is a history of fringe forms that permit one to navigate the field, or else make parts of the field opaque. If viewers have never seen an experimentalist work, even the shortest movie can feel like a lifetime. But in those minutes that feel like hours, something extraordinary can happen, and the process of attention can snap into focus. Then we’re not just watching a path unfold, we become the path.

Cristina: There are many ambiguities in your films, are these transcriptions from life, or else generated as fiction? When we hear someone speaking, the positions of ‘I’ and ‘you’ are unclear and ever-shifting. And there is also an ambiguous relation of image to sound – we can’t always tell which came first. What attracts you to these ambiguities?

Mike: Let me say a few words about Buffalo Death Mask (2013). I had a single hope for this movie, though it had to be abandoned in order to make the work visible. After I became positive (aka seroconverted) I learned how to look in a new way. Not because of the new divide between those who were and weren’t positive, or because of whatever ideas separated the dying and merely unwell from the robustly healthy. I’m speaking in a physiological sense, at the level of sensation and perception. I learned in those years, surrounded by so many who were dying, to be able to see how a body ages and dies in a single instant, the same way a speech glitch or a yoga posture or a DNA molecule synthesize generations of inclination. I learned to see the way that light came from bodies. Our dying selves emitted a very particular quality of light that I woke up to in the waiting rooms of Vancouver General Hospital, where an entire generation of men had turned into the walking dead. They were sad and angry and defeated and undefeated and beautiful and terrifying and each emitted a light that I could see when I could get over the sheer difficulty and terror and mirror-holding prophecy that each of us became for each other. We were a promise for each other. Today it’s me with the facial lesions and the cane. Three months ago I was bench-pressing four hundred pounds, now I can hardly get out of bed. And one day, only too soon, it will be you. But out of the chests of these cane wielders and bent-over skeletons there was a rare and beautiful light that I learned to trust and was able to find more reliably as the frequency of my visits increased, and I became involved in the local version of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power).

Many of the images of Buffalo Death Mask feature this quality of light, they show light coming from the body, and this, more than anything, is what I wanted to share in the film. In fact, in its earliest versions, which lacked any dialogue, the hope was both to demonstrate and to teach the viewer this kind of seeing. The movie would act as a secret workshop, and show viewers what it had taken me a fatal illness to discover: that our bodies transmit light. But when I ran it for my first audience, who are always my friends Gary and Steve (I call them the music, when the movie is done, it is time to face the music), they assured me that they couldn’t see a thing. Yes, sure, there were moments of beauty, but they remained far away. Why should we care? This is what they told me. Turn these faces into something that matters. Apparently, these pictures needed the company of words. As usual, I had come to the end, only to find myself returning back to the beginning.

These pictures required the company of language, I would need to have a conversation, but with whom? When I thought again about this particular quality of light, the face of Canadian artist Stephen Andrews arrived immediately. While he’s shape-shifted his way through various mediums, and offered a very painstaking, home-schooled and hand-made luxuriousness, there is something instantly recognizable in what Stan Brakhage would call his “motion picture thinking.” Because Stephen had learned to see in the same death school I attended, his pictures are infused with the light that comes from bodies. Sometimes I find myself standing in front of a blob of yellow and orange, or a building silhouette, or a construction worker gesturing at an undressed ceiling, and I can’t help crying because I can feel the roots and the cost of this work, and just how much he has managed to bring all the way over from those plague years onto the canvas.

There was also an entirely selfish reason for talking to Stephen. I wanted to ask him how he had survived not dying. Before the cocktail, we had prepared ourselves for the end, but who could teach us how to live on after this moment and embrace our second life? This has become a very pressing question for me lately. I muddled through the post-cocktail years, dragging survivor’s guilt every step of the way, and now, these many moons later, it’s all come round again, like a taxman collecting dues. Why should we still be here, when so many are gone? The unspoken pact I had made with my friends was that I would go first, but I would gain the consolation of not having to watch them die. Now that my friends are dying I find it unbearable. I want to jump into every grave and take their place.

Buffalo Death Mask unwraps two kinds of time: now and then. The bodies are swathed in light because this is the way we died back then. But it’s also about today’s necessary conversation where Stephen burnishes his grieving with lightness and hilarity (how else to hold an unholdable past, not to mention surviving one’s own end?).

As for the authorial ambiguity you mention, the shifting place of the speaker, I think that in psychological terms the project of fringe movies is to dethrone the King or the Father, so that we might live in a kingdom of children. Though there are always those ready to anoint someone to the throne.

The notion of the commanding author, the one who is telling you the way things are, is often put into question in my work. In the film I made with Steve Sanguedolce called Mexico (1992), the narrator (who addresses the audience as “you”, as if they were the one making the trip down south) keeps projecting his home town (Toronto) onto the new Mexican cities he encounters, often we see iconic Toronto moments even as he insists we are deep inside Mexico.

The most personal instants in my movies are the ones that are most contrived, or appear as borrowed bits and pieces. How did Oscar Wilde put it? Give a man a mask and he’ll tell you the truth. And on the other hand there are also absolute diary moments, footage made on the run, drawn from life, but these are usually asked to perform a particular service for the movie, so quickly turn into fiction.

Adrian: Your films really examine the ‘I’, the subject, the individual self. It sometimes seems as if you seek to flee or escape the prison of the self. Yet, at the same time, your experience of AIDS-related illness has necessarily (as your films document) put you into an extraordinarily intimate relation with your own body, and the bodies of those close to you. Where do you stand in relation to ‘self’?

Mike: When I swapped 16mm film for video back around the turn of the century, I started making portraits, a very traditional artist’s pursuit. There were feature length movies about my friend Tom, as I mentioned, along with my editor Mark Karbusicky (Mark (2009), and video dad Colin Campbell (Fascination (2006). But I troubled this suite of portraits by marrying the biographical genre with another subset of fringe movies that might at first glance appear strictly in opposition to portraiture. I became interested in Duchamp’s Urinal, and the floodgate of stolen pictures that were flushed from its handsome porcelain interiors. How might a collage of borrowed pictures serve the interests of portraiture, or to ask it another way: how could one create the signature effect of an individual out of stolen material? Could the decisive moments of one’s life belong to others, even the memories and pictures of unmet strangers?

While this might seem a stretch, the most usual adult interface is language, and I don’t know about you two, but I haven’t invented a single word yet. All I do is steal other people’s words, entire phrasebooks are boosted from those living and dead, and are happily projected out of my mouth with alarming regularity. I continue to speak as if these were my words. I often hear political opinions, for instance, expressed about faraway countries that are obviously stolen, or half-stolen, from some local pundit, or those bland corporate engineers who are paid to deliver the news of the bosses. My expressions of desire seem rather obviously culturally conditioned, how would I know about love if someone hadn’t got there first and told me all about it? What seem like rash impulses, electrical storms, neural firings, are also subject to the borrowed redescriptions of language, where we tell each other what we want, and how far we are willing to go to ensure we will never get there. Lacan put all this so economically when he wrote: the unconscious is structured like a language. Ditto ditto.

What I’m trying to do is play with the ideas of figure and ground here. The stolen footage should be the ground, and the figure should be the great woman or man, the one who speaks their truth, the singular expression that can only arrive with their face. But if a fringe audience member can find their singularity by gathering in a collective, perhaps the fringe biography arrives at subjectivity only after it’s detoured through everyone else’s pictures. The question of borrowed, second hand memories is also the world of immigrants of course, where the old country is superimposed onto the new one, and the ensuing double vision is often driven by sharp memories that don’t belong to the one who has them.

What I’m trying to locate is subjectivity without subjugation. How can one arrive at subjectivity without having to be something less, without having to re-enact the walk out of Egypt?

Damaged (9 minutes 2000) is a 16mm film made entirely from a collection of postcards purchased from a single shop. Out front it boasted a carousel of turning views that might have contained fifty pictures in all, and the restriction in making this film was that I could only use these pictures. The question is how could I make a film with these pictures, which were immediately suggestive of a biography, of a life that I might like to lead, for instance, in place of the one I have. What pictures am I going to choose, or what pictures are going to choose me, in order to become who I am? We have been trained by our culture to forever emphasize our differences, our particular traits and eccentricities. When I was in grade school I remember practicing my signature again and again, in different styles. Is this one me? Or this one? When I was young I longed to declaim my differences, but as I get older I can’t help but notice the similarities. How we love to defend our tribe by naming another as an enemy. How filled with fear we are so often, not to mention our shared anatomy. We all walked out of Africa together, and our physical differences became a reaction shot to our geography. If we are so intent on expressing our differences, perhaps it’s because we are anxious about how alike we actually are.

Damaged is about how pictures from the outside become pictures projected inside the body. The pictures offered to a person becomes the way that they’re going to live their life. There’s a series of women that take up this picture-making role for him: mother, sister, wife. In the end, the narrator dissolves into a uniform collective that paints houses. Here is the usual postmodern credo granted a picture: the surface has become the inner life. I’m all here on the surface, and we’re all here together. As if I couldn’t be myself until I’m part of everything, or everyone.

Cristina: You’ve mentioned the constant revision of some of your works. With Public Lighting, specifically, what have you changed?

Mike: The opening section had a languorous opening shot where we crossed a body of water on a ferry. I had imagined this as the necessary approach to the movie. But over time I grew increasingly impatient, and longed only for the happiness of the other side. So the first section, Writing, was radically re-edited. In order to create a high definition video file, all of the found footage from the Madonna and Philip Glass sections had to be regathered, so these sections have been recomposed. The opening title is completely new, and the intervening chapters have received small and large interventions.

Adrian: The film begins by announcing (through its first ‘character’) the idea that there are six basic personality types. Does the rest of the piece stick to that structure and illustrate it? Is that structure evident or did you deliberately abandon it?

Mike: I had hoped the structure was clear, though your question suggests otherwise. The first chapter is called Writing, and features Dutch writer Esma Moukhtar. She announces her project which is also the project of the film, to narrate the six kinds of personality, the six kinds of sadness, of knowing. Not a stereotype but a hexatype. She makes this curious statement, “I follow thoughts that don’t seem to belong to me, that don’t belong to my life. I call them Public Lighting.” It’s as if she can only know herself by knowing others. And of course this sentence marks her as the author of the Public Lighting movie, once again troubling the notion of author and identity that lies at the heart of this film.

She goes on to say: “”I’m going to tell you six stories, sometimes with the voice of a man, sometimes in pictures and together they’ll be called Public Lighting. They are case studies, biographies, which will demonstrate the six different kinds of personality. They will constitute my work as a young writer.” Pictures as work, as construction zone, as the place where personalities are made and unmade.

Let’s look at one of its chapters. It’s called Hiro, shortform for Hiroshima, the first city to be devastated by an atomic bomb, and coincidentally the real life name of its main character, the actor Hiro Kanagawa. Hiro plays a man who has a camera in place of his personality. He uses his pictures to distance himself from events. He’s drawn to spectacular mishaps like fires and tragedies, possibly related to the fiery destruction of Hiroshima, but he doesn’t have a heart relationship with what he sees. In the final scene he steps out on another night prowl, he wants to see something, but he also wants to stay separate from what he’s seeing. He enters an alleyway in Vancouver’s notorious lower east side, the poorest postal code in Canada, where he spots a man lying motionless on the concrete. Is he dead, does he need help? Hiro raises his camera to snap a picture but he can’t. He puts the camera down and speaks the first word of the movie, “Hey.” The entire movie exists to make this word possible, it shows Hiro coming into language, from the psychodrama of his camera solitude to the tentative embrace of a stranger’s life. After speaking he actually does something, he calls an ambulance. This gesture signals his coming into subjectivity, he becomes a subject by reaching out to someone else, and this is symbolized by the entry into language.

Adrian: Your preferred term for the kind of movie you make is fringe film, rather than experimental, alternative, avant-garde, etc. In your Masterclass, you also evoked the concept of micro-cinema: small, fleeting exhibition situations that are not necessarily for mass audiences …

Mike: Not that I would mind that! My phone is waiting…

Adrian: … but how do you conceive the audience (real or potential) for your work?

Mike: I think you’re asking after the old problem of naming. Once you’ve made a thing, then it requires a caption, a genre perhaps or at least a genus. What kind of a thing is it?

My work is usually named fringe or avant-garde (though I think of myself as a documentary maker), so the most usual place for it to appear is in programs alongside other experimentalist movies. This invites similarly like-minded audiences of artists who make these kinds of movies – along with programmers, distributors, professionals. I feel a bit defeated by this scenario. Of course it’s fine some of the time, but when it becomes standard practice it means that my movies are condemned to viewers who have already seen too many of them. It feels politically regressive if we can speak only to members of the same subfamily, huddled together babbling our specialist dialects. I try to put handles on my work, handholds where viewers who have never crossed an avant moment can still find a purchase. I have my mother in mind when I make my movies, she’s very smart, but never grew up with any visual culture. How to continue this old conversation we’ve carried on, instead of retreating into the secret codes of the secret society? There’s an inevitable tension, I think, between the increasing depth of specialist practice that one develops as an artist, and an audience who is not engaged in the field. Can I walk into a contemporary dance performance, or avant poetry moment, and find something like pleasure, even though there are quotations I am missing, necessary backgrounds that are being turned inside out? Making a film means seeing it a thousand times, while a viewer has it rush by only once. Could there be pleasure in our encounter, humour even, friendly points of entry? The political question is: could we use this diligent work on form to touch a world, even to suggest different shapes for a world, that can make new forms of encounter, even new kinds of living, possible?

Cristina: We are fascinated by the montage style of image and sound in your films. How do you build these montage structures? We are especially intrigued by your use of superimpositions and dissolves.

Mike: The movie about my friend Tom Chomont began in two moments, when I think of them together there is already superimposition. The first was a telephone call in which he recounted his newfound delirium at all night dance parties. Early one morning he had sex with a beautiful stranger, and couldn’t tell in that exhilarated moment whether he was using condoms or not, and a couple of weeks later he came down with a flu that aroused suspicions he might have been infected with HIV. Two weeks later his doctor confirmed the news, not only was he positive, but as it turned out his customized virus was already immune to some of the available meds. Meanwhile his Parkinson’s had grown worse, and he had been let go from the legal firm he’d been temping at for the past decade. He was broke, unable to work and physically unwell. It was a devastating moment.

A couple of months later I was at the Impakt Fest in Utrecht where I remustered with my pal Caspar Stracke. As soon as I saw him I wanted to spend every waking moment together, so we contrived to make a movie. I told him about Tom who we both agreed was eminently deserving of a movie memorial or three. Let’s start right away! Caspar posed a single condition for our collaboration: that I had to get this newfangled and dreaded thing called email. I was resistant because my friend Joanna had introduced me to the idea of email, and told me she had broken up with her girlfriend during a rash session of email exchanges (you mean, you type the letter and it gets sent right away? I had to ask her more than once), and in a single afternoon, what had been a blossoming three year romance was dust. Email, I sniffed at her, showing off my extraordinary powers of divination, that’s a fad that will never last.

Because Tom was in such rough shape, we needed to find a way to have him come across, to have some of his Tom-ness arrive, without simply pointing the camera and asking him to tell us the whole shebang. Above all we didn’t want him to appear as an object of pity, never mind that his limbs would shake, or else freeze up entirely, owing to the Parkinson’s. There is nothing pitiable about Tom, not a note, he remained more lucid and dignified and erudite than the whole upper east side gentry right up until the last moment.

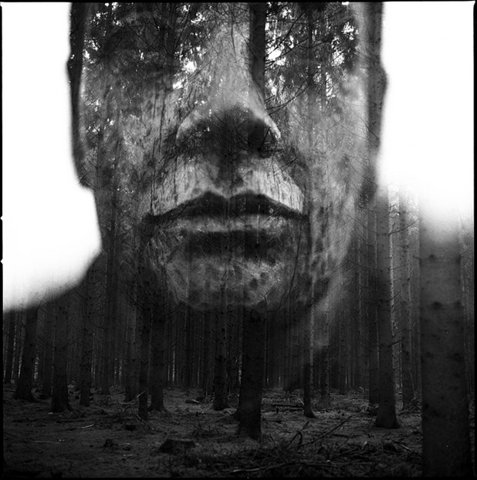

You used this beautiful and strange word: superimposition. Even as we’re speaking here together, there are so many pictures between us. Each word you say sparks off a memory, an association, a picture flash. There is already here, in this perfectly ordinary, and entirely mysterious scene, where everything is lit in the same rain-filled, tungsten-assisted overhead sheen, there are duets, and triplets, and quartets of pictures that are overlapping, dissolving into one another. I learned how to look at faces by seeing them very slowly, and very quickly, backwards and forwards, in my editing machines. And as we are presenting our faces to each other here, I can’t help but notice how your faces keep changing, from wonder to scepticism, from a distance that seems close, to a leaned up curiosity. We imagine that our faces present a continuity through time, but actually they’re a superimposition of many archaeological moments that flicker in and out of focus. The more that you can open to someone, or the more that they are willing to show you, the more obvious it becomes that what in cinema is called superimposition is actually a lived documentary trope that arrives whenever people are intimate with each other.

I think the body is made of memory. And sometimes that memory can arrive through the way that someone touches you. In this movie, Tom becomes a kind of projection screen, and we become projection screens along with him. Where do I stop and where do you begin? This is the question that haunted me: can I let him touch the part of me that I haven’t found words for yet? Can we take the risk of changing each other, and can we offer these pictures as evidence of that transformation?

Tom was part of the New American Cinema. They were Bolex heroes of the sixties, set off on a visionary quest that privileged hyperbolic subjectivities. How these mothers and fathers would cringe to see their hard-won singularities turned into genres. Tom introduced Robert Beavers to Gregory Markopoulos, and his vividly edited shorts are part of that strain of homo-fringe aesthetics, though more diary inclined, threaded through a cascade of white light.

I remember the first time we sat up until late in his postage stamp of an apartment on Elizabeth Street, just west of the Bowery, when everything in the room became lighter and lighter. Every object glowed, the whole apartment swam with light. His eyes would get slightly crossed and this great shit-eating grin would cross his face and hang there for an hour or three. This white light was a regular accompaniment to our sittings, and he found a way to reproduce it in his filmwork by making a high-contrast black and white print of a scene, then superimposing that print with the original colour reversal. The effect is that the highlights blow out, granting a radiant white sheen to everything, while the shadows are crushed. The high contrast roll acts as a matte, so the colour image appears only where there is black in the image. I was amazed that he had uncovered a technique to reproduce his experience. It was named “experimental” of course, but it was actually documentary, he was being utterly faithful to what he saw.

To return to your question about superimposition, this bloom of white light is also a kind of “real life” superimposition, and then Tom found a way to share his particular way of seeing via the filmic trope of superimposition.

Adrian: Another question about structure. You often use a structure of parts, a mosaic structure – whether multi-screens in one screen (Frank’s Cock, 8 minutes 1993), or the successive stories/portraits in Public Lighting. Is it a basic part of your artistic make-up to approach things in this prismatic way?

Mike: I try to think of each movie as a progression of scenes. Where does the scene begin, how does it develop and close? What is the trajectory of the scene and how does it transition into another? Buffalo Death Mask is framed by superimposed faces moving in slow-motion, they offer an entrance door to this mysterious world, and then an exit door. During the approach there are a series of titles that speak about meeting: how do we say hello, how do I walk into this room of a film? It also describes the meeting of two lovers that might also be the meeting of a film and its audience. The final scene is relieved of the need for language, so there’s repetition with a difference. In between these two doors there are a series of scenes that begin with a wide shot of the city. In classical Hollywood grammar this is the establishing shot, offering a view of the city, which should be followed by a view of a house, and then two people talking inside. But instead of a close-up of talkers we have the close-up of two voices, and a montage that is associative.

After the framing shots, there are two sections of voice-over conversation with a musical interlude between them. The first convo ends with Stephen talking about his partner Alex who died of AIDS. He says, “Not only do you lose them, you lose what they remembered about you. And if you don’t fully understand yourself, then you’re doubly bereft.” In other words, we’re made up of each other’s memories. Then we enter the interlude, two hands come together in the water, echoing the lone hand that we saw near the film’s beginning, again: repetition with a difference. There are a group of people gathering in a smoky light, as if we were all HIV positive. Then we return to the conversation where Stephen and I talk about life after death. Am I dying today? As Stephen puts it, “It took me three or four years to put Humpty Dumpty back together again.”

In my earliest years I made work with senseless abandon. What I needed was to find a way to organize material, to grasp the most elementary modes of audio-visual structuring (albeit ones that lay outside the shot-countershot ploys of dramatic cinema). But lacking mentors or ears open to reasonable advice, I created many obscure universes of film.

One day I chanced across the work of Matthias Müller. I could see very clearly, even in the operatic Super-8 experiments he made in his living room: “Oh yes, this is the beginning, this is the middle, this is the end of the scene, and that is followed by another scene.” Of course, he’s come out of the closet since then and announced to the world that he is Hitchcock’s numero uno fan. Everyone needs a father, if only to know who we have to say no to eventually. Matthias had Alfred, and I had Matthias.

Cristina: Your films are often about the experience of intimacy between two people. But, as you said in your Masterclass, this is always also a threesome, because something intervenes or mediates: the camera. And then there is, finally, the audience (small or large) that watches the film. How do you relate these realms of private and public?

Mike: I feel that montage creates a very basic movement that Freud described as ‘fort da’ [‘gone and there’]. While editing I need to be very close to the material; to feel the rhythm of every cut as it arrives. You’ve been making digital reworkings yourself, so you know that if you shave two or three frames from the head or tail of a cut, it’s the difference between a sharp breath and a prolonged one, these few frames articulate the flow, the eruption, the pulse. The length of the tail of a shot changes the way the next shot is received. It can also elaborate the end of a gesture, like the gesture of walking out a door, which could be the very last door, or else, only part of an endless series of doors that you’ll never have to stop walking through. When will we ever come to the end of each other? The end of your smile?

I need to be close to every cut, but then I need to be far away; I need to look at the footage as if it belonged to strangers. I’ve never lived in this house before, what are the customs here? It’s difficult to maintain, this movement of back and forth. When I move away from the material, I’m trying to occupy the place of the audience who have a fantastical vantage: they are able to see these pictures for the first time. While editing, I’m always shuttling between audience and artist.

Cristina: What about the music in your films? You obviously have a strong feeling for music. Do you make music yourself? How do you work with it?

Mike: I love music but I never learned to play a note. When I was a teenager, vinyl scratched out the words I hadn’t learned to say out loud yet. The emotions my body was aching to perform. But these were received wisdoms, I had been tuned up by corporate culture, and one day I left the whole vinyl collection behind in a rooming house basement. When I didn’t have any records left, I could start listening again, not to the locked grooves of dominant culture, but simply to whatever was happening around me. Getting sick was the key. Others take up the violin, or learn to knock out piano chords. I got mono. Kidney failure, hepatitis, there was a long series. And after each prolonged bout of illness, after the entire world shrank to the size of my body, I would stagger out of the front door and hear every delicious car horn, I could hear the wind singing through every blade of grass. Illness helped me to wake up to sound.

When we were working on the movie about Tom, Caspar introduced me to a new kind of music he was very enthusiastic about. Caspar is forever jumping into new cities, new situations, he’s absolutely fearless. To be honest, when he first played it, I kept waiting for it to start. When is it going to start? He looked at me puzzled, no, no, this is it. Sometimes, when I burn a disc for friends, they’ll take it home and wonder if something is wrong with their speakers. No darlings, that’s the music playing. It can sound like plumbing gone wrong, or the deep rumble of a congested chest. We used to love the label Mille Plateaux before the man behind the curtain blew everyone else’s royalties on a French dominatrix. Today I love the music of Machinefabriek most of all, he puts out a new sumptuous collection each month, and has generously furnished some of my work with musical accompaniment.

Music remains a kind of ambition in my work. Everything aspires to the condition of music: the pictures, the sound, the voice. Everything rolls out as rhythm, synergy, pause, breath, pulse, expulsion, crescendo. There is a feeling tone that music instantly produces, underlying whatever we might think about what is going on, that cuts against, or works to support, events in the picture plane. I often work with many, many tracks of loops and atmospheres and drones, and while I am struggling to find a shape for the movie that my mother, amongst others, might find sensical, what is driving the project is some internal urgency of rhythm.

Adrian: A final question. I don’t see you as one of those anti-theory, anti-intellectual filmmakers. You’ve clearly been interested in it as part of our life. Hearing your Masterclass, I got the feeling that every good, useful theorist is, for you, a type of artist. How does ‘theory’ – or rather, particular theories – figure for you as an artist?

Mike: How I treasure the words you write about cinema, Adrian and Cristina, but also, as an artist, I need to find a way to survive them. How can I survive your fatal truths? Perhaps I could take them, or anything recounted in this interview, as part of what Roland Barthes called “the science of the particular.” Its laws wouldn’t hold across all time and circumstance, but would obtain only in a single instance, a hapax legomena of science.

I love so much of what Barthes wrote, particularly the passages I don’t understand, which far outnumber the ones that make sense to me. It’s nice to walk off the cliff holding someone’s hand, don’t you find? I adore his curious, idiosyncratic work about photography, Camera Lucida, where he reads the history of the medium as a fairytale of family. And the most important person in the history of photography is… his mother! Of course, she is also the most important person in his life. He creates a theory of photography with his notion of the punctum, the piercing point, the part of the picture that hurts you, and that draws you to it, that separates it from the rest, out of the history of his relationship with his mother. His perfect sentences arrive from a place of breathless intimacy, you can feel how much it cost him to write these words, what was at stake in looking at a few photographs, and his ability to translate that into something that even a stranger can share.

For the past three years I’ve been reading the effortlessly prolific British post-child psychologist Adam Phillips. He sees patients in his office every day in the week except for Wednesdays, which is when he writes, and he produces a book every eight months or so. I turn to his pages just for the pleasure of running my tongue over his immaculate phrases, he is a maxim machine. In his last book, Missing Out: In Praise of the Unlived Life (2012), he’s very interested in the question of frustration and obstacles. He suggests that obstacles show us what we really want, and as someone who has grown perilously old, I’m still trying to swallow that one. Frustration is a greatly undervalued quality for Phillips, he feels that it is the ground from which creativity arises. If everything’s flowing, if you keep coming up with answers, then why would you invent something new? The Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgard said much the same thing about his epic, five book monument called My Struggle. The 3,500+ pages were preceded by a period of four years where he couldn’t write at all, and he insists that the act of not writing, and the act of writing, are intimately joined, that without the not-writing, writing itself would not be possible. Though our culture is trained only to look at the exhale, not the inhale. We are accustomed only to focus our attention on the achievement, the accomplishment, the expression, and not the years of frustration and blankness. Why aren’t our magazine covers filled with avatars of frustration? Wouldn’t that be so much more helpful, rather than seeing all those award winners strut past?

As an artist, I think Phillips is asking me: how might I court frustration? How might I create an eco-system of frustration in which I could find new solutions? Right now, I’m five years deep into a movie called We Make Couples. It’s about the question of the place of couples within capitalism, and how a couple might replay the questions of capitalism between each other. For instance: am I turning you into my exclusive property? Is monogamy an extension of real estate? Do we own each other, in a certain sense? Am I presenting myself as a particular brand? What if that brand changes – is that OK? Often as couples grows older they have kids, which requires having good jobs, and then they have to live in good neighbourhoods, and a nice house, etc … And then, all of a sudden, you look like part of a system, a supporter of the status quo.

But could the couple also be a form of resistance? And, if so, in what way? In the movie a couple of people ask each other these questions, trying to find forms and contents that might swim together. They are asking: how can we live together? What if getting what I want isn’t what I want? The geometry of couples, is it a rule, what about plankton or pyramids, are there other more supportable structures?

Theories are swirling around us, and when they sing through your body, and the bodies of the city, then they’re alive, and it’s beautiful. When they’re used as a big stick to tell us how it’s supposed to be, then it’s time to turn those answers into questions again. Or?