Mike Hoolboom’s Frank’s Cock (1993) and Buffalo Death Mask (2013) are both structured as reminiscences, dialogue-driven accounts of a time in the mid-nineties when the AIDS epidemic was at its deadliest. In the former, Callum Rennie delivers a monologue about Frank, a gay man dying from AIDS. Rennie speaks from the perspective of Frank’s partner of nine years, marveling at Frank’s vivacious and sexually voracious nature as he mourns the imminent passing of his lover and friend. With Buffalo Death Mask, the voiceover conversation between Hoolboom and artist Stephen Andrews is similarly retrospective. It takes place in 2013, ten years after the time of Frank’s Cock, and from the other side of the release of the “AIDS Cocktail” in 1995, a drug therapy that transformed what had been a death sentence to a manageable, though still fraught, affliction. The two friends, survivors of a disease that claimed so many lives, share memories of lost loved ones and the era that is vanishing along with them.

Both films’ accounts of the AIDS crisis are permeated by loss. This is felt in an acutely personal way, through intimate details about those who suffer from and eventually succumb to the disease. Frank, in Rennie’s telling, is larger than life. We learn that he cracks bottles open with his teeth, has “a thing for omelettes,” and makes ample use of his titular endowment (he has a penchant for fucking to the sound of the CBC). Such stories, however, can only approximate the presence of a man who we never, and will never, see. Rennie’s own face, addressing the camera in a stark black and white composition, only occupies one corner of the screen, initially surrounded by darkness. As he speaks the other three quadrants gradually fill with footage of microscopic organisms, fragments of Madonna videos, and scenes of sex between men. The images, and the music that accompanies them, amount to a lively din, like multiple televisions playing different channels turned at once. With the description of Frank’s illness that ends the monologue, however, the other images return to the darkness, a reminder that even this healthy, robust man, stricken with Karposi’s Sarcoma like so many others, will eventually fade.

The loss that pervades these films is compounded by the fact that, when loved ones die, so too do we lose the parts of ourselves that they carry with them. In Buffalo Death Mask, Andrews describes this as being “doubly bereft”: “Not only do you lose them, you lose what they remembered about you.” In this way, loss is not singular, but extends to friends, lovers, and, beyond that, entire communities and even a generation. This broadened scope, which stretches far beyond the individual accounts of the films’ narrators, is suggested in their richly layered imagery, particularly with Buffalo Death Mask’s 8mm footage of artists in their studios, people gathered in crowds, and time-lapsed images of the Toronto cityscape.

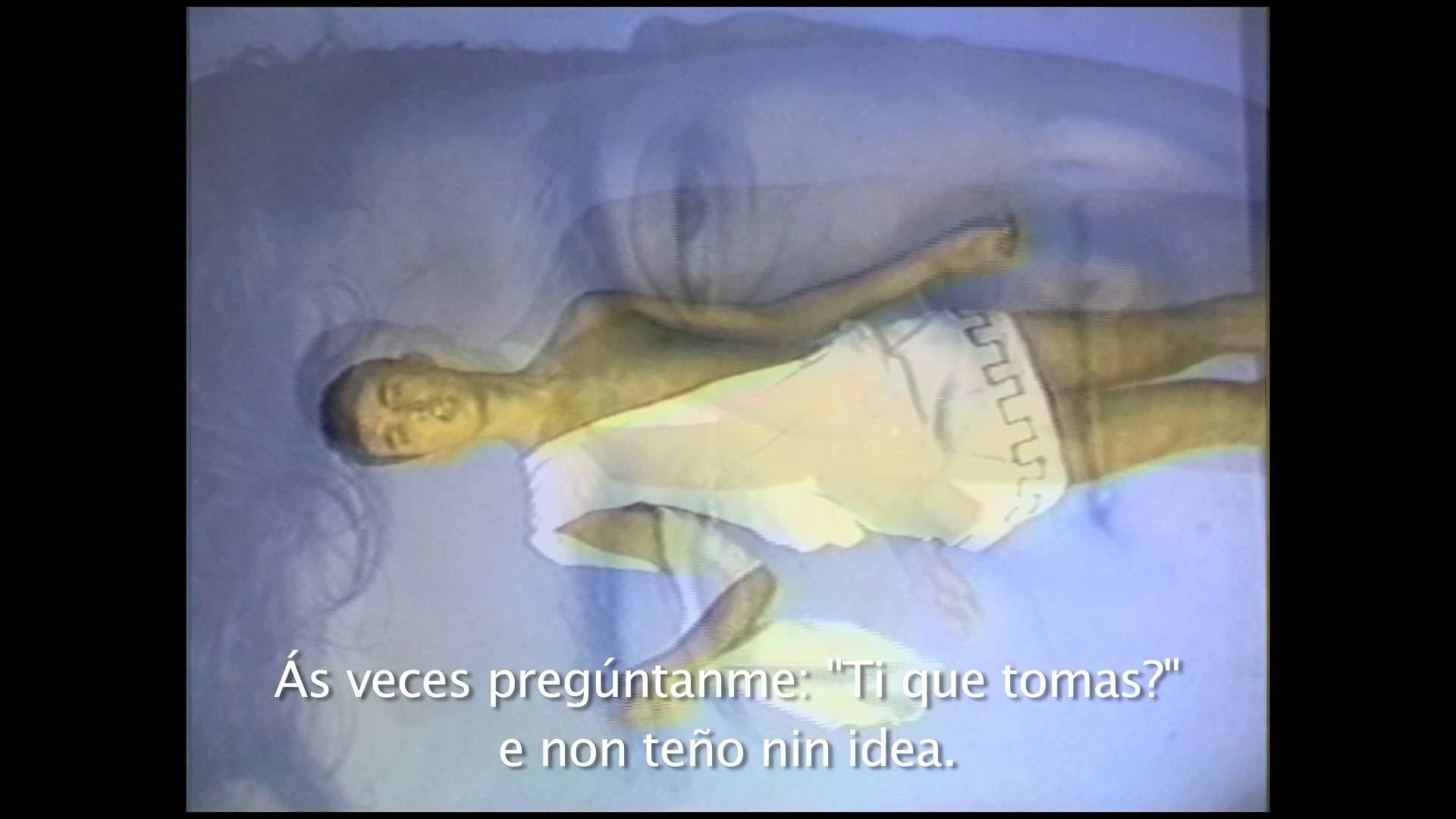

Frank’s Cock and Buffalo Death Mask do not only revisit the past through dialogue, but also stage scenes of retrospective viewing. Both are themselves ways of looking back. Frank’s Cock was made by compiling four channels of video footage and rephotographing it with a Bolex. Film, the elder sibling medium to video, is used to gather and add dimension—chiefly grain and a sense of depth—to Rennie’s first-person narrative. The look back in Buffalo Death Mask, meanwhile, involves a longer delay between the shooting of the source material and the compilation of footage. Hoolboom retrieves footage shot from a decade prior, around the time of the making of Frank’s Cock, and reworks it digitally, slowing down the image of his friend, Mike Cartmell, who had since passed away. At the beginning of the film, we see Cartmell’s face in extreme close-up, his eyes closed and covered with coins like one of the shades ferried by Charon to the underworld. Cartmell was already dying at the time the footage was shot, but it is the dusty, grainy footage, the slow dissolves from one frame to another, his squinting and deeply shadowed eyes, that suggest the completion of his passage to the other side. Somehow, in that earlier moment, something of the future was glimpsed. The footage is like a time capsule, not a frozen moment of the past, but a message to be delivered to the future, to our own time. And rather than letting him fall into the Lethe, a river that causes forgetfulness, Buffalo Death Mask retrieves Cartmell, and lingers over his image.

The moment both films return to is the early nineties, when the AIDS crisis was full-blown. As a disease that has disproportionally affected the gay community, it threatened both from within, claiming tens of thousands of lives annually in North America, and from homophobic forces without, including the public stigmatization of a “gay disease” that, among other things, delayed crucial medical research into treatment. The arrival of the AIDS Cocktail antiretroviral therapy, mentioned in Buffalo Death Mask, dramatically affected mortality rates for HIV/AIDS, and it marked a juncture between those who died and those who were lucky enough to receive the new treatment in time. Both groups, however, were indelibly shaped by the disease, and seropositive individuals like Hoolboom and Andrews have since carried the guilt of survival and the burden of memory. In handwritten text that appears across the bottom of Cartmell’s slowly turning image, Hoolboom asks, “why are we still here when so many are gone?”

Memories of us are carried with the dead, and we in turn hold on to traces, however insufficient and partial, of their lost lives. The time before 1995 is, in many respects, irretrievable, largely because the culture around HIV/AIDS has profoundly changed. Though there is plenty of media documentation of the time “before,” and in this way many of Hoolboom’s films join the important artist and activist work of organizations like ACT UP and Visual AIDS, the current moment is threatened by a different, less visible, and less urgent conception of the disease, truncated from its deadly past.

Frank’s Cock and Buffalo Death Mask restore this sense of the disease’s past, and the lives it claimed, through an attention to the materiality, and attendant fragility, of bodies and film. At times, film is treated like skin, speckled and wounded, as when we see the spray of shingles across Hoolboom’s torso in Buffalo Death Mask. “The body remembers,” he says in voiceover, and so too are his films charged with remembering. They not only record the stories of Frank and other lost loved ones, but bear the marks, the hazy texture, of memory itself, like photographs worn from repeated handling. We see, in Buffalo Death Mask, grainy Super 8 footage of a man walking down a city street, engulfed in passing headlights, and, toward the end of the film, a group of people gathered in a fog, their figures barely discernable. As they dissipate, first into the orange cloud, then into darkness, we see their faces turned upward. What are they looking at? An airplane, a star, some other kind of light? Though the film does not reveal the object of their attention, the scene recalls the earlier image of Cartmell’s eyes covered with coins. These tokens that secure passage to the other side are also a way of seeing, a look to some point beyond, and a viewpoint that Hoolboom’s films ardently strive to share.