Mike Hoolboom’s prolific film and video work offers us the project of attention. His movies are an intersection of faces, texts and pictures, all offering space for its viewers. There is an open-ended quality to his best work, it is securely fastened, but in place of a definitive stop there is a conjuring of further roads that might be travelled, other thoughts that might occur to the viewer. It is a cinema that demands close attention and encourages free association at the same time. It delights in polyphony, in bringing together elements that patently do not belong together, everywhere there is a queer maximalism on display.

What to make of the artist’s ever-dwindling oeuvre, that appears under constant revision? A filmography at the Images Festival retrospective twenty years ago reveals more films than appear today, the more he makes the less is evident. Art making is a procedure of gradual disappearance, a vanishing act. And how else to disappear except through the mechanisms of display and projection?

Song for Mixed Choir is the artist’s first film, a baby step, made in film school. Already there is a concern with materials, with grain in this instance, the image beneath the image. The movie lifts its title from Heinz Holliger’s Song for Mixed Choir, a choral piece that the artist has brought together in a gesture of radical collage with turning grain patterns and incidental pictures. The rhythm of this intersection already holds a signature movement, an underground rhythm that the artist will return to again and again, even in his most recent encounters.

Public Lighting

Recut a decade after it was made, Public Lighting poses this core question: how is a self constructed? The answers unfold across seven visually distinct chapters, construction zones where each subject pushes and pulls at the containers of their subjectivity. The movie’s credo might be delivered via an Anne Carson quote in the opening salvo: “Every wound gives off its own light.” In order to become a subject, each of these people are wounded, sometimes through gender, race, or a stranger’s pictures, and we watch as each of them turns to forms of media to project their self formation. Public Lighting’s portrait essay miniatures are delivered via fan fiction, unreliable narrators, amnesiacs, audio-visual graffiti. It opens with writer Esma Moukhtar announcing that she will write a text entitled Public Lighting, and project her voice into unknown lives. The film is a box within a figure of speech within an enigma. How to pull together its voices and personalities?

The chapter called In the City features an alternating current of humor and pathos, there’s no separation of the two. The narrator, voiced by fellow fringe auteur Steve Reinke, describes a series of break-ups in restaurants, a cornucopia of sex and sustenance. It describes the parallel universes of insatiable desire and an insatiable consumer culture. The bio portrait of Philip Glass, on the other hand, has none of the irony of the loveless love song that precedes it. Glass takes shape as a portrait of New York City, a proliferating series of views that the composer relentlessly channels into a narrow outlook. The film is a celebration of limits, and the freedom that becomes possible, the self that becomes possible, within those boundaries. The camera-wielding protagonist of Hiro is similar, he observes, responds to, and inscribes his city. Threaded through his observations are moments detailing the nuclear destruction of Hiroshima, and these views inform his seeing, they become part of what he sees, even as he tries to contend with his new present-day home in Vancouver. Tradition’s heroine is similarly haunted by memories she never had, by a homeland (China) that she visits as a tourist, before becoming a tourist of memory itself. In the final chapter, Amy, the narrator recounts a dream where the mass media adopts her voice. As usual, the subject is doubled, projected, reproduced, part of someone else’s mediation.

The closing song, riffed from the Beach Boys’ God Only Knows, talks back to the Madonna song cycle in an earlier chapter, where her blondness lives inside a self-made world designed for maximum observation, a forerunner of social media constructs. Though Facebook wasn’t even a college wet dream when this movie was begun. The Madonna section takes shape as auto-visual graffiti, a fan/love letter is written over some of her most familiar pictures, which describes an affair, but also her growing old. She lives in the public eye, she lives to be seen. The film brings together these two sides, these two strains: she’s visible and not positive, while the writer is invisible and HIV positive. Of course the writer is an unreliable narrator, this fan letter could be the product of delusion, as well as a critique of her media-soaked life. What does it mean to make a work that responds to its time, and then refashion it according to the needs of another time, at a later date? Can a work transcend its own conditions and become readable according to the needs of another historical moment? Can it be malleable enough, produce an open system that can be adapted to unexpected encounters?

Frank

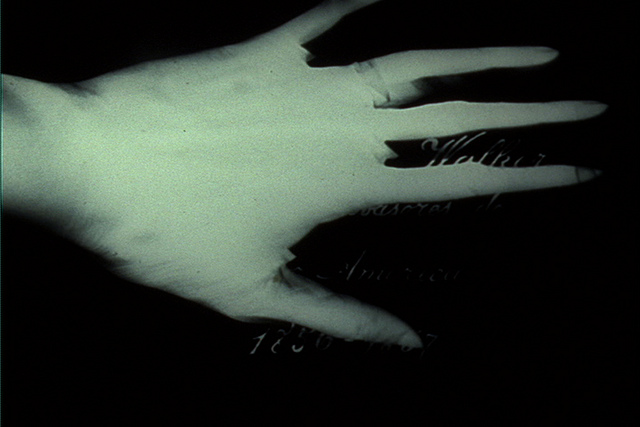

Frank’s Cock (1993) is a work from the early 90s that is already playing the artist’s melody, a signature he has tried to resist using a range of formal approaches. But here are the multiple images and sound collage that are so familiar from his more recent video featurettes. The film enacts this fantasy: what if I could watch four movies at the same time? The interest in overlapping layers, the singular monologue that becomes real through fiction (the more the artist makes up, the more often he projects his voice through others, the more honest the work appears). The poignant and haunting monologue that is at the heart of this work has a familiar ring for those versed in Hoolboom’s work. There is a sense of the breadth of a person’s living and dying in these sentencings. The speaker offers decisive moments from Frank’s bio and the viewer is invited to fill in the rest. Unlike the digital imperative, shared by security agencies the world over, that every scene be rendered in exquisite detail, so much of what is on display here can’t be seen exactly. There are microscopic cellular worlds and then bodies in sexual communion, but the viewer is invited, again and again, to fill in what is missing. How to make a place in a movie for what cannot be said or shown, how to grieve what cannot be represented?

Tom

Tom (2002) is another recut movie, newly shortened, I remember the relentless density of the first version, but here the proceedings are calmer and more stately. When I saw this for the first time I’d never seen anything like it, there’s no precedent for documenting someone’s interior life using found footage. No one else has approached the problem of the portrait with this marriage of two seemingly incompatible genres: the documentary portrait and the found footage film.

The subject is Tom Chomont, the New York film and video artist, encyclopedic raconteur, SM scenester, suffering from Parkinson’s Disease. Could we call the face a symptom? The subject presents with a variety of symptoms, he is top and bottom, leather bound and wearing negligee, frail and impervious. The cascading montages are interrupted by the filmmaker’s personal asides. In a key moment, he recounts a conversation with a fellow sex worker, who shares his feelings of inadequacy and love. When he begins to cry he begs Tom not to tell the other guys, he wants to retain his mask, the wall of perfectly good looks that keeps everyone at a necessary distance. But over and over again this movie shatters this distance, producing intimacy using clips from the filmmaker’s own work, as well as an overwhelming variety of pictures from every possible source. Slowly Tom’s world begins to wither and fade, his father dies, and then his beloved brother. The artist himself is seen slowly and shakily self administering pills. The final moment sees him holding a half mask in front of his face, trembling, staring at the camera with an uncommon intensity. He drops the mask revealing the face, and poses this question to us: am I still wearing a mask, or are you?

Buffalo Death Mask

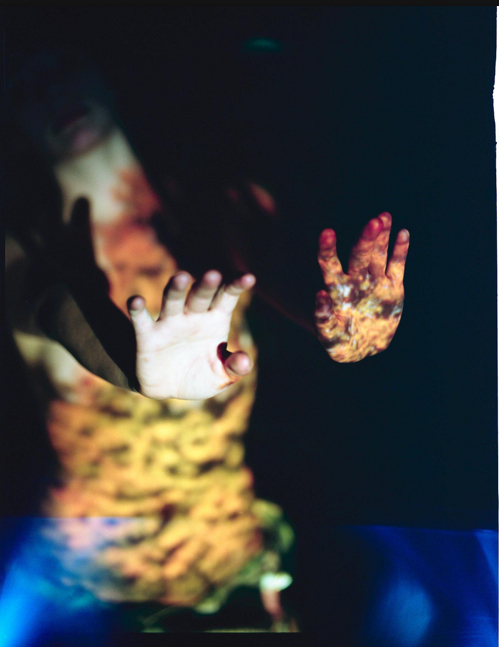

Buffalo Death Mask is framed by intimate moments amongst friends. The faces are seen in close-up and slowed down, magnifying the smallest moment, even as the in-camera superimpositions produce a continuous flow where portraits appear and dissolve. Intertitles describe a caregiving scene between two friends, one may be dying. The question of survivor’s guilt (though this emotional shorthand doesn’t begin to cover the horizon of grief). Who is left to speak?

These scenes frame a conversation between the filmmaker and Canadian artist Stephen Andrews about being HIV-positive before the arrival of the life saving drug cocktail. Here is the heart of the work. Visually dense with a kinetic montage attuned to bodies that emit light, the pictures are in a continual dialogue with the conversation, offering parallels and then counterpoints, sudden openings and eruptions that admit new faces into the room. One could find one’s own self in it, it’s not only about Stephen Andrews, somehow his friend parade becomes my friends.

After narrating yet another near-death moment, Stephen argues that no one exists alone, we are made up of each other, we have become the sum of our meetings, relationships, memories. When our friends die, they take with them the versions of ourselves that only they could know. This mesh of interbeing suffuses the film, making the shadows light, and allowing these survivors to touch the most difficult places with laughter.

Retrospective programs

1. Public Lighting (75 minutes)

2. Frank’s Cock (8 minutes), Tom (52 minutes)

3. In the Theatre (6 minutes), Mexico (made with Steve Sanguedolce) (35 minutes), Buffalo Death Mask (23 minutes)

4. Song for Mixed Choir (8 minutes), Southern Pine Inspection Bureau #9 (9 minutes), House of Pain (50 minutes)