Originally published in Panorama Cinema, March 2015

The prolific Canadian artist, a specialist in biographical excavations and thaumaturgical narratives, Mike Hoolboom takes his inspiration directly from the heart. His pictures begin with the innermost secrets, as a whisper, a caress. While the approach is experimental, the sincerity of this humanist quest raises the pulse of even the most indifferent moviegoers. Faced with the prospect of such artistic communion, it was difficult to resist the weekend invitation by curator Karl-Gilbert Murray whose two-screening retrospective titled Fringe Dreams is another flashpoint for this unique programmer, and lovingly perpetuates the hard work of memory and memorials.

Spanning more than twenty years of work, the five films in the selection (Frank’s Cock (1993), Tom (2002) Damaged (2000), Mexico (1992) and Buffalo Death Mask (2013)) provide an enriching overview of the director’s career. We discover many of its most exciting qualities, including virtuosic image recycling driven by delightfully anecdotal narratives, a sensitive emotional impressionism, and his unwavering desire to remember, which seems to have been precipitated by his HIV infection at the end of the eighties. We discover with pleasure a filmography of surprising coherence and unfathomable density, led by an infectious humor that never ceases to remind us that the joy of living may trump the spectre of death.

The Resurrection of the Plague

Elegant and hyper-compressed epitaphs, both films in the first program (Frank’s Cock and Tom) are vibrant homages to their subjects, constantly reaffirming the archaeological power of the film medium that is so keenly felt and powerfully evocative that it becomes contagious. The speakers offer passionate and captivating testimonies, and their remarks are accompanied by archival images that are expertly researched. The two works perform a double miracle, not only do they perform a sublime emotional finessing, they offer to their subjects the marvelous gift of cinematic immortality.

As its name suggests, Frank’s Cock is an intimate ode to a lost lover and his prodigious penis; this sincere and touching admiration reminds us joyfully of the male organ’s most admirable characteristics. Using a simple four-screen technique, this short eight-minute film evolves in the manner of small chamber music, the rhythm varying in intensity as the inexhaustible words of a talking head evoke a life of bodies and alphabets. Additional images of microscopic cells, burlesque shows and gay porn move the viewer’s attention across the screen. But the film is finally carried by the memorial speech of the narrator who confronts his partner’s decline with a disarming simplicity, even as he continues to revel in the biological reality of the body, the source of hedonistic delight that deserves to be pampered even as the prospect of death grows near.

Tom is a biographical chronicle of New York underground filmmaker Tom Chomont. It is an infinitely more complex song of mourning, impelled by a sublime kaleidoscope of borrowed images that evoke not only a single human journey, but the path of an entire city. “This is my city,” Tom announces in the movie’s earliest frames. Particularly intimate shots of Tom shot by Hoolboom are accompanied by an endless stream of sumptuous and evocative clips, scenes from international films of all periods, extracts used always in a sensitive and profound way. The work of this impeccable craftsman has created an impressionistic biography.

The use of superimposed images create a teeming visual landscape that underscores Tom’s biographical narrations. The images do not simply follow one another, they overlap and dissolve continually like memory fragments handpicked by Hoolboom to better expand the movie’s impressive emotional quilt. The movie benefits from a scholarly association of ideas, focusing especially on the rich comparison between the physical construction of the New York skyline by immigrant workers in the early twentieth century and the artistic building done by Tom. The film is framed with the building blocks of his ancestors creating a metropolis that is equal parts steel girders and imagination. Tom also proves Hoolboom’s unparalleled talent for inventing emotional landscapes, cleverly borrowing from popular culture to skillfully create intelligible illustrations of interiority, offering us a subterranean entrance to his subject.

Dust Mirror

With an equally exciting and careful selection, the second program delves further into the image recycling work of the director, who manages to transcend his pictorial contents with a heavy poetic narration that carries personal and metaphysical implications. In Damaged and Mexico he detournes a photographic portfolio and a travel video, converting them into teeming universes of meaning, lit up by the piercing gaze of the director. The second program continues the analysis of remembrance as a remedy for death, crowning the retrospective with one of his most personal films, Buffalo Death Mask, where the artist displays his herpetic eruptions, but also the most agonizing reality, the gradual disappearance of earthly life.

As an appetizer we begin with a delightfully accessible film called Damaged. Composed of a series of archival photographs (popular images) handpicked to draft an anecdotal biography of a narrator, this short work of eight minutes crystallizes all the genius of the director who manages to pour pop culture effortlessly between the subject of the film and the audience, turning individual experience into common experience. Miraculously managing to match the right images with the right words under the sign of an astute and friendly humor, Hoolboom creates a truly communal experience. Here is the biography of every and anyone ready to succumb to an unbearable nostalgia of the moment.

Technically similar to the previous film, Mexico is a travel film whose voice-over acts as counterpoint. It is a much more ambitious project, if only because of dizzying spirals of association related to its images, while the narrative continues to add philosophical depth and unexpected poetics. The voiced text also deepens the context, it creates an offscreen space as vast and mysterious as the soul itself whose feelings spread the screen. The sight of a bartender busy cleaning glasses is accompanied by a description of languorous television watchers glimpsing their dreamed doubles. Even the bones of Jurassic researchers, stupidly framed in the manner of a television report, here reveals their secret Machiavellian theatre, their simple actions of cleaning thickened with a speech about remembrance and death.

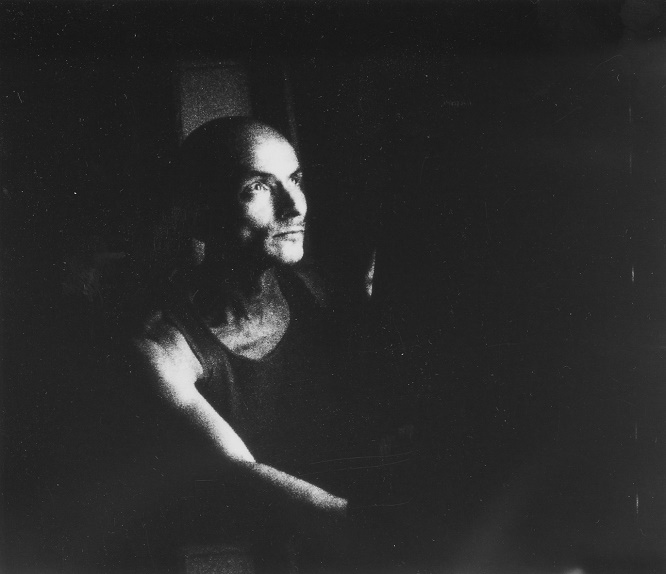

The ultimate offering of curator Karl-Gilbert Murray comes in the form of Buffalo Death Mask, the latest film from the director and an obvious example of the sense of urgency that has characterized his production since the nineties. Punctuated by a dialogue between Hoolboom and Toronto artist Stephen Andrews (who is also HIV-positive), the film is a twilight portrait of the filmmaker. But it does not simply take this opportunity to record his image, but also to oppose the degeneration of the physical body. He deploys a variety of techniques to demonstrate the body’s decomposition, from pronounced photographic grain when framing faces, to offering up the same face, young and old, in layers of superimposition, many subjects appear overexposed under ghostly lights, chromatic decomposition of anatomical curves…

Pushing the Borders

Despite the breath of life that the famous drug cocktail grants those who are hiv-positive, Mike Hoolboom continues to “deteriorate” rapidly, constantly accentuating the sense of urgency that characterizes his work, trying always to record his generous soul the better to better push death and preserve forever the disturbing humanism that animates it. In this way illness transforms his entire filmography into a vibrant still life woven from warm memories that replace perfectly, as imperishable residues of a finite existence, the fruits and golden treasures of the classic era. It is our only remaining hope that these movies will transcend the fragile shell of the director, preserving forever his golden heart in our collective memory.