(from the book Jeux Serieux by Bertrand Bacqué, Cyril Neyrat, Clara Schulmann and Veronique Terrier Hermann, HEAD Geneva, 2015)

In this short movie of Mike Hoolboom’s, we are met with a fathomless crossing of pictures that have escaped from the maelstrom of movies, comic strips, advertisements and other lost video species. The film’s first hyperbolic setting is a virtual city in the manner of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, recast here as a living comic strip that hosts those without a fixed identity. Passersby are caught in a web of attention that slows down everyday movement, seized in the gravity of a great sky, centered in a low-angle shot. Then Hoolboom summons a corridor of shadows, torrential disasters, family scenes troubled by the erosion of the silver surface of the film, and before long the human body explodes into myriad evanescent pixels.

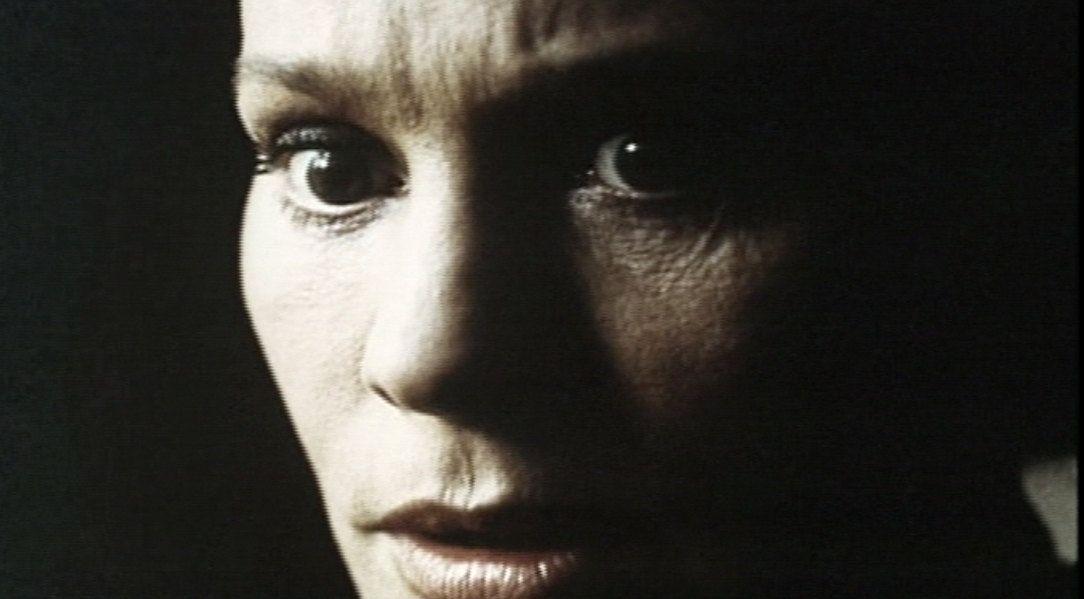

At the heart of the work of this Toronto-based director — a central actor on the stage of Canadian experimental cinema — is a non-conciliation between the world of homes and their images. From the incessant flow of images, the dripping magma of a moving and mesmerizing matrix of film, there emerges a demiurgic will, the unexpected story of a rescue. And this rescue is enacted so that we can watch death at work. We face striking proposals, sometimes held in the serious and silent gaze of Liv Ullmann and Ingrid Thulin, sometimes frightened by the cadaver of a disarticulated donkey abandoned in choppy waters. The links between pictures are never explicit but proceed instead via free and poetic associations. This method of accumulating film fragments creates a complex series of relationships, they are moving layers in a densely thick fluid.

For thirty years Mike Hoolboom has developed an art informed by clear existential questions. In this instance titles embedded within the composition provide rhythmic assertions on life and cinema.

Intertitle: We are left

Image: young mother and child and the beginning of a deluge

intertitle: with pictures in place of memory

Image: a young woman prisoner in chains

intertitle: dialogue instead of conversation.

Every title fragment returns us, and bears us away from, the entire film complex, it is a haunted threnody that breathes before and beyond any representation.

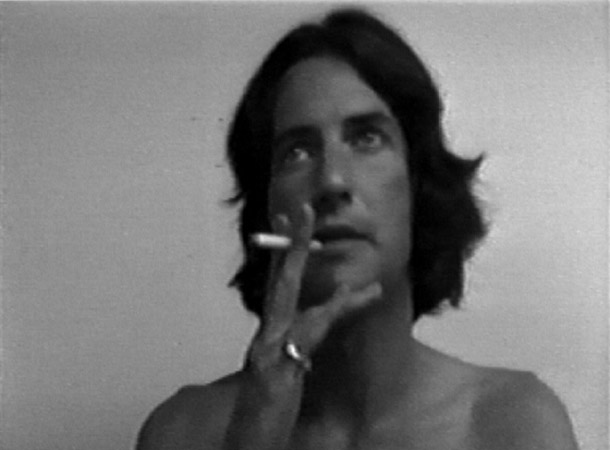

What a shock when the corridor shown at the movie’s beginning leads to a film theatre in which fantasies of immortality are born and where we can at last meet the dead. It is in this theatrical metaphor (containing all the stagings of self and the world) where the author seeks the presence of a missing relative, Colin Campbell, part of the first generation of video artists in Canada. (Hoolboom made a more extended, feature-length biography of him in 2006 with Fascination). Campbell’s name is withheld until the last frame of the film, and so this unnamed ghost haunts every scene. Perhaps he is that dumbfounded child, wide-eyed and looking away, or maybe he is in the car that glides through the air across the frame. In the Theatre feeds on all of cinema!

Mike Hoolboom gathers solitude around him as a necessity, he’s a distinguished iconoclast whose inspiration is drawn from his persistent encounters with the cinema. In this instance overexposure delivers compassion instead of contempt, the insatiable eye of the looker yielding unexpected returns. His work is engaging, testing the restraints of these pictures, the way they have already taken over his body and the social body, where he is trying to undo some of the knots, delving into the palimpsest of pictures, tombs for the eye, in order to reconfigure them, bend them to newer purposes. But even as he exercises a relentless editorializing judgment, he releases these pictures into a new fragility and vitality. Here is cinema saved from the shipwreck, newly fertile and singular, which we can lay down with in our beds, tired from our too many memories.