Originally published in: (FIDMarseille Daily)

Vincent: How did you arrive at the idea of re-using images 40 years after they had been made? Did you have to go through a lot of Jeffrey Paull’s images while making the selections for your film?

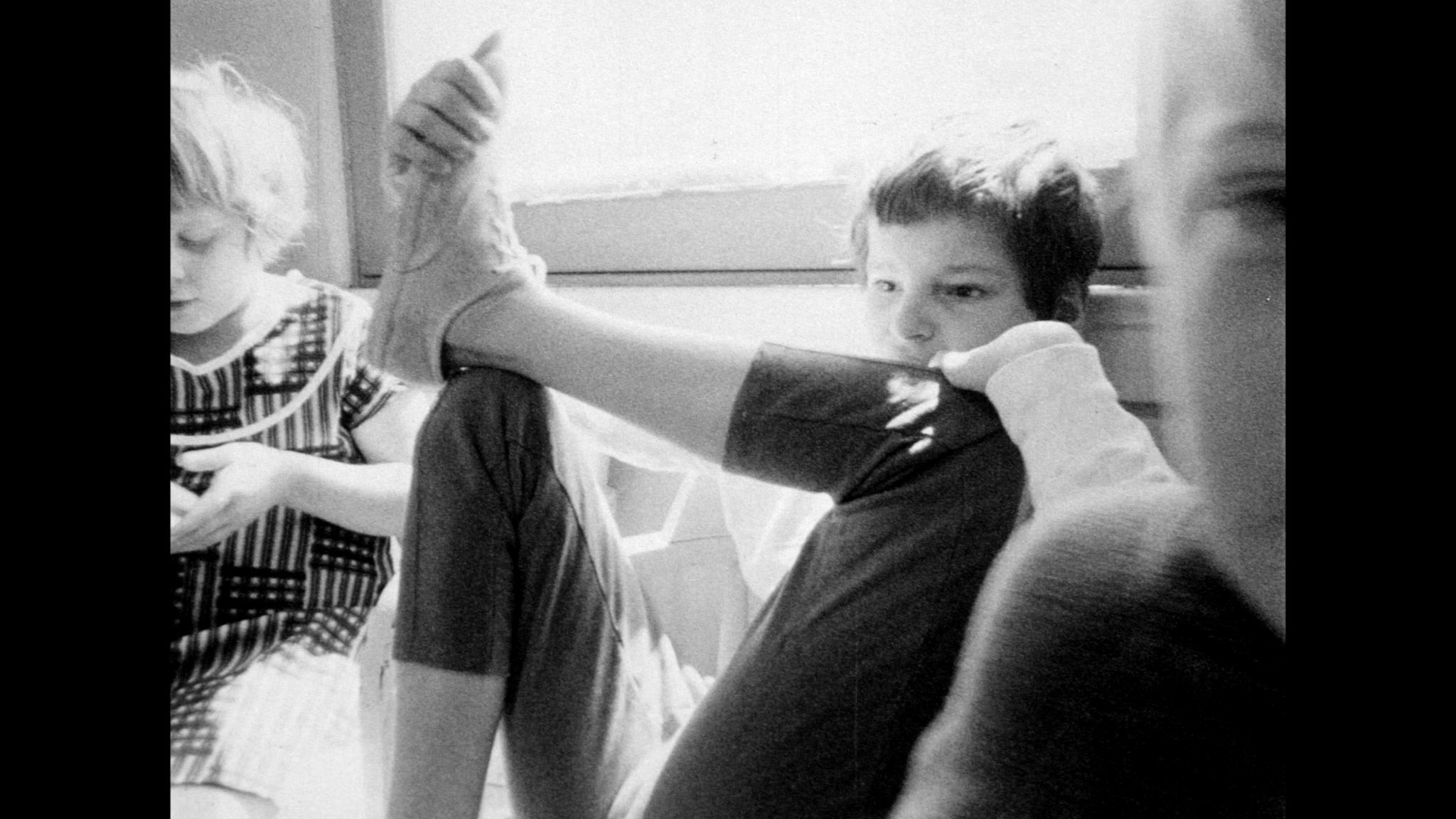

Mike: Shortly after he graduated from Boston University’s thrilling film program in the 60s, my friend Jeffrey was hired by the Broadview Developmental Centre in Ohio to set up a darkroom, and work with the kids there, help them take portraits and learn how to use cameras. It was a utopian moment for the new field of media studies, everything from feminism to animal rights might be reimagined using portable imaging technologies that would allow even the most marginalized voices to author their own expressions. Jeffrey shot half an hour of film there, and the footage sat for many years until he gave it to me. I also let it sit for a few more years, wondering what to do with this gift. Wasn’t it Lacan who said: love means giving something you don’t have, to someone who doesn’t want it? Sometimes it can take a long time to see an image. That’s what I think both of us were waiting for, we needed to find some way to make these long ago pictures present again, to make them visible.

Vincent: Donna Washington used to be a patient in an institute for mentally challenged kids. How did you meet her?

Mike: We met online, like so many do these days. How else to find folks outside of our usual patterned grooves? She is shown in Jeffrey’s footage scribbling out the film’s title.

Vincent: Donna Washington thoughts are surprisingly constructed. Could you tell us more about this?

Mike: Donna is autistic, she experienced feelings (good or bad) as overwhelming in intensity. She struggled for many years to be able to separate her identity from the furniture, or a drape, or someone else. The experiences she describes are very close to those narrated by religious mystics who recount a flow of interdependence, a shattering of boundaries. But the mystics didn’t live in this state permanently. Donna struggled for many years to draw a border around herself, and one of the ways she did that was through language. She has described her journey and her experiences many times, in a variety of settings, clinical and otherwise, so perhaps it’s no surprise that she is so articulate in the movie’s voice-over.

Vincent: Finally, it seems to me that Scrapbook (18 minutes 2015), by delivering different faces to those mentally challenged kids, is in line with your films dealing with HIV — fighting other people’s looks, going beyond biased ideas. Do you agree?

Mike: Yes, this movie tries to give voice to someone who is too little heard. My movies around AIDS (Frank’s Cock, Safety Film Collection, Buffalo Death Mask) similarly try to voice an experience that is commonplace for millions round the world, yet the media swaps out personal experience for numbers, science talk and fear. The voice of fear is too often the voice of the authority, the surrogate parent, the president, telling us what is no longer possible, about why we have to stay small and separate. Perhaps these movies are a way of turning certainties into questions again. What would it be like to meet each other without fear?

One of the biggest questions for those who have been delivered to the scientific miracle of the HIV cocktail resurrection is: how do you live twice? How do you invent your second life? This is further explored in a recent book co-authored with trans artist/activist Chase Joynt You Only Live Twice (2016) (http://www.chbooks.com/catalogue/you-only-live-twice). Part of the role of fringe movies is to narrate different lives differently. Form and content can’t be separated.