Chris: Can you briefly describe what the Funnel was?

Mike: The Funnel was an experimental film collective. Like the old Hollywood studios, the membership was dedicated to a combo production-distribution-exhibition colossus. Four home-made movie theatres were built in three locations, a modest distribution collection with catalogues were dished round the fringe movie planet, gear was available for locals. There was an art gallery, publications, open screenings, a radio show and the theatre hosted 40+ screenings often with artists in attendance.

Chris: What made you decide to do a book of interviews about the Funnel?

Mike: I wanted to connect to earlier modes of anti-capitalist resistance. Haha. Different times.

Chris: How would you say the Funnel contributed to anti-capitalist resistance? One could say that the Funnel sounds like a nascent Lightbox. What was different?

Mike: You’re asking how the Funnel and TIFF Lightbox are different? Wow. The Funnel was a co-op mostly run by volunteer artists. We were interested in the kind of success that money couldn’t buy. There was nowhere to get to, no careers at stake, no one had a car or even a TV set. We wore second-hand clothes and lived in cheap and illegal spaces in unwanted neighbourhoods. There was a lot of time spent in and out of the theatre hanging out, drifting. We used culture to create a space that was separate from the useful citizen model.

Chris: Was there anything particularly revelatory in the stories you found in the interviews you conducted?

Mike: There were sentences uttered years ago that still have the talismanic power to hurt, to draw blood.

Chris: It’s my understanding that you were not a fan of the Funnel back in its day, or at least around the time of its closing. Can you explain that position and how it’s changed?

Mike: Well, I was part of the collective for a long stretch, so in part you’re saying that I wasn’t a fan of myself. Hmm, perhaps you’re right. We didn’t offer workshops in that, perhaps we should have? There were a thousand kinds of sweetness but exits were generally played for maximum awkwardness and bad feeling.

Chris: That was a bit clumsy on my part. I was referring to your advocating that the Funnel move its equipment to LIFT (see attached letter to the CCA). Perhaps a better question: what’s your sense of what led to the Funnel’s demise?

Mike: It’s true, I think Funnel gear should have gone to LIFT, instead of vanishing or being sold off piecemeal to individuals. Shouldn’t the extensive Funnel archives and gear belong to everyone who put time into the org, instead of those few left at the very end? Who is allowed to stake a claim, to have a voice and be part of the record?

The Funnel’s endgame makes up the entire third chapter (of three) of the book. Various threads are explored. An open membership was key. Rising real estate costs, leadership crises, modern vs postmodern. Could an org that had grown tall by embracing materials make the turn into a politics of representation when members started to make work that was identity-based, even embracing non-canonical forms like animation or dramatic interludes? Who gets to decide what properly belongs to the field of “experimental film,” and what is an outlier and unwanted? Unsurprisingly, these same tensions are still being played out today.

Chris: Why did you choose these particular films to represent the Funnel days?

Mike: Midi Onodera and Judith Doyle were both staff members and key filmmakers in the collective. Jim Anderson ran the distribution collection, was a founding member, and offered an easy-going entry to strangers. Unlike nearly everyone there he had made a swatch of movies before the Funnel started up, some with his pal Keith Lock. His feature-length opus Gravity is Not Sad But Glad was clearly influenced by Mike Snow’s Rameau’s Nephew, which both Jim and Keith worked on. Peter Dudar was a performance artist who made movies, a mainstay on CEAC’s European tours along with Lily Eng (together they formed Missing Associates). I hoped that along with Lily and Jim, he would conjure some of the org’s difficult pre-history.

Chris: Was there a house style to the work?

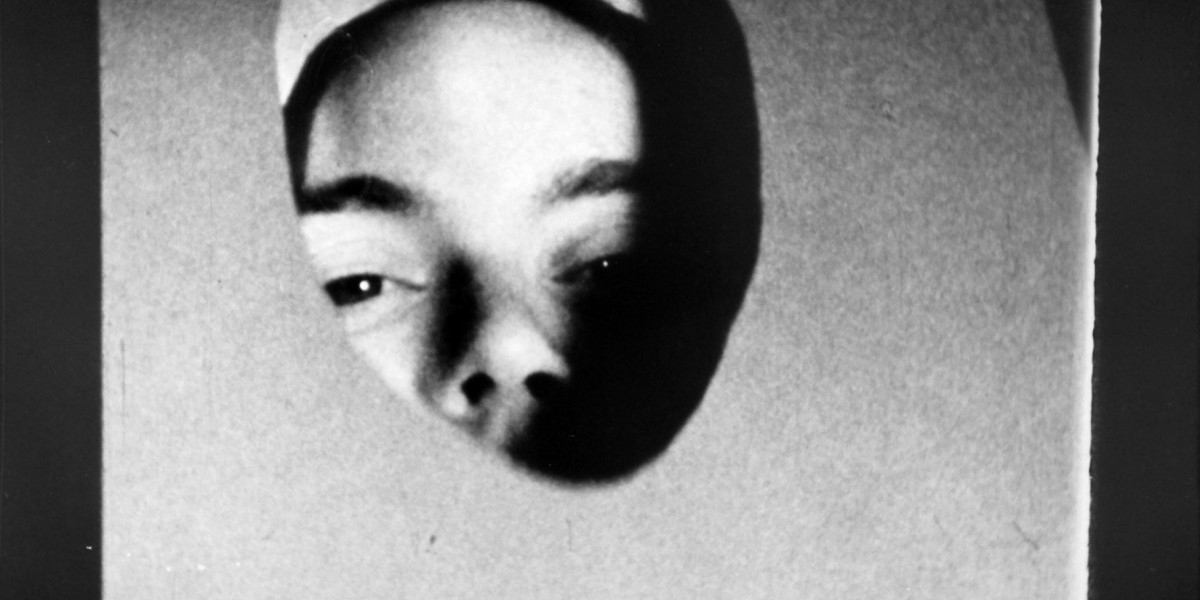

Mike: I’ve dedicated an entire mini-chapter of the book to exactly this question! There was a general lack of money, so low-to-no budget was a commonplace. There was a lot of super 8, which discouraged editing. Many were busy making their first works, so a general interest in tools, materials and processes seems inevitable. Notebooks but not scripts. Shorts were the rule. Avant godparents (and Funnel members) Mike Snow and Joyce Wieland’s influences can’t be overstated.

Chris: Are there any lost gems you wish you could include? Or interviews you weren’t able to complete?

Mike: There is a lost film made in an all-women workshop by Katerina Thomadaki and Maria Klonaris called Studio Mirrors (35 minutes super 8 silent 1985). I’m almost remembering a film called I Want to See My Mountains by Peter Gress. Ian Cochrane’s anti-nuke film (optically printed to death). Judith Doyle’s three-minute miracle of hilarity made for an opening season of shorts, shot on the way to Kodak (to drop off the roll of film so it will be ready for the screening) as her mother (behind the wheel) harangues her (“Judith… you’re always late. You always wait for the last moment…”) Jim Anderson’s movie that collaged leaves onto leader. (No one could believe it actually made it through the projector, and it was so beautiful).

Chris: Did you find any inspiration from either this community or their films in your own work?

Mike: I made my first movies there, minor catastrophes, something less than sketches. Work outs? How grateful I am for having the space to fail so completely. How to be an artist without failing? There was a fantastic roll out of local, national and internationals on parade. It wasn’t hard to see each other’s work, meaning that we were part of an ongoing international convo. I worked next door at the photo lab until midnight, and then I would swing by, work all night, and go home before the day shift started up. The art of attention, the narrative that isn’t a story, the sincerity of making with less. We were all in it together, though everyone had to find their own way.

Chris: Is there any resonance you find with this current day and age, or anything we could learn from the past?

Mike: We live in a city of winners, a neo-lib triumph. Little wonder that local artists have such a difficult time getting work shown here. What could resistance look like? Are collective models sustainable, and could they take shape to serve community needs? Has media art become another movie genre – the province of curators and specialists – or could it still carry some of the political weight that marries new forms with new contents? If collective action weren’t scrummed round architecture or gear, what other rallying points might be found? What could the organization of disorganization look like?