- Invitation (pdf)

Whenever I went home my mother used to ask: are you seeing someone? Are you going to bring someone home for Christmas? But after awhile she stopped asking, she turned the story, the love story she imagined I was always part of, into another story. She swapped one version for another. The new version goes like this: Mike is in love with his work, therefore he’ll never really be committed to another person. That place in the body that most reserve for their beloved, (and she imagines it exactly like that, as something that occupies space, like a building in a city), she tells herself: that building in that city is already occupied, it has a full time tenant, and that tenant’s name is work.

My work, and my love, and my love for work, and working for love. When I made a movie about my best friend it was dangerous and difficult because she was the brightest, funniest, wittiest person in every room she ever walked into, but someone very different when she was alone, when she wasn’t so busy presenting herself. I was interested or aiming at these reluctant and unspoken truths, and finally resorted to fiction, hiring an actor to do her voice-over for instance, because her own sounded unconvincing. To live inside this zone of intimacy, where every touch, every glance is amplified a thousand times, and it’s all so dangerous, because those long years between you can vanish, just like that, and all of a sudden your best friend is just another faceless face on the street, never wanting to talk to you again. This is when documentary can become fiction can become documentary.

I never loved my friend Mark until he died, and then I threw myself into arms that were no longer there. I rubbed myself into the face of his wounded friends, his shattered partner, his stunned family. I wanted to arrive too late, and stand in the full heat of his suicide, his abject, death-wishful servitude. I needed to bag my picture trophies and carry them away home, where I could pore over the feel-bad moments again and again, in between increasingly strained or distant or difficult encounters with the real life counterparts, the forever guilty reaction shot to Mark’s impossible act and accusation. Call it the cost of making pictures. And sometimes the cost of love.

The illusion in this digital moment is that pictures are everywhere. I hold my cell phone out in front of me and snap, there it is, the present, frozen in that instant, digitally retrievable, framed, dated and archived moment. The picture, I have it, it’s mine. But mostly, I find, there are no pictures in my camera. The illusion is that the digital camera creates pictures instantly, but anyone who is serious about making pictures understands that a picture never arrives all at once. Pictures require time, and even, I’m afraid, as Roxy Music’s Bryan Ferry used to say, more than this. Yes it looks like a picture, there are picture elements, there is a frame, a composition, there is colour and light. But I remember a story that John Berger told about trying to draw the face of his good friend. He started in the early evening hours, and drew all night, steadfastly, diligently, using up one piece of paper, and then another. Here the nose was too large, here the expression in the eyes too dull. It takes time to create a picture, and more than this. By dawn, Berger was surrounded by the crumpled remains of his drawing pad, but he had managed at last, by a great and trying effort, to create a picture of his friend.

How can I make a picture? Is this a question of work or a question of love? My mother would say: He can’t tell the difference, there is no difference, anymore. For me, I need to enter the picture first, before the subject arrives. Before the subject arrives, I have to arrive. I have to be there first. And I have to create a certain kind of space around myself, I can’t arrive for instance, ten seconds before the train is leaving. Clothes trailing off me, items spilling out of my suitcase, oh wait, the train’s leaving, omigod. I can’t do it in a rush and frenzy, I need to arrive with space around me, space enough to wait for instance, to wait for someone else to arrive. To wait for the light, to begin to create the time that will show up again later, in the picture. And more than this.

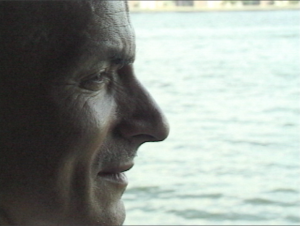

When I made a movie about my friend Tom – someone sometimes paralyzed with Parkinson’s, laid low with AIDS – I knew I would have to travel a long distance in order to find a way to make a real picture of him. At the very least I would have to fall in love with him. And because I couldn’t, I did the next best thing, I fell in love with my collaborator, and each picture we made together and stole together and cut together shone brightly with the evidence of our feeling and intensity, until we couldn’t any longer. And then I was set off alone, but already inside the picture the love had already made its seal, and made these pictures possible as evidence of that seal. I stayed up all night, for two years, and then it was done, the mask of his face and the mask of mine, smiling together.

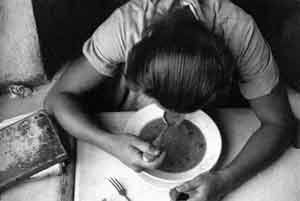

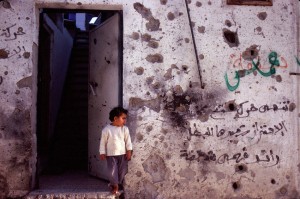

I am working right now on a movie called Lacan Palestine. My friend Andrea writes me and asks, I understand why you have a lot of sex in the movie, but why are you doing something about Palestine. This country that is not yet a country is a kind of pornography of the image world. Used and used again by first worlders with cameras. How can I tell her, how can I begin to explain, the darkness of those months, how every day seemed unendurable, impossible, unbearable. The only thing I had were these pictures, already made by a friend ten years ago in the Occupied Territories, during the building of the so-called “security barrier”, the woman weeping at the death of her daughter, the children pumping water, the boy banging his bottle with a stick. There was no door in the room I was in, no hope for reprieve, nothing but a horizon of punishment. In this movie, the autodidact philosopher says there are two kind of personalities: the obsessive and the hysteric. The hysteric is haunted by this question: am I a man or a woman? The obsessive, the workaholic, the one who will never do enough, whose primary affect is guilt, is haunted by this question: am I alive or am I dead? Or am I alive? Or am in love? Or am I dead?

To find these pictures, to make a place for myself in these pictures, it was first necessary to be laid low, to be disastered, as the philosopher states, to be without the star that ought to guide one. Shipwrecked and foundered. To be a Palestinian, even here, in the luxury of our first world difficulties and comforts. To allow these pictures to touch me, it requires a great surrender of so many things I had imagined were myself, were the very heart of myself, it meant going so much further than I thought I ever could. To find you there, waiting, on the other side. Not to make you mine, not to remake you in my image, my hope, but to find you in all of your unfinished loneliness and otherness and separation. Yes, it’s true, after all this time, it is the Palestinians, or even the pictures of Palestinians, who are showing me, who are teaching me, how to go on. How to love. And more than this.

This chat was delivered as part of:

Toronto artist/architect Adrian Blackwell presents a new instance of Model for a Public Space. Staged in the Reading Room, a students’ social space located in Hart House at the University of Toronto, Blackwell’s project is concerned with the inevitably knotted nature of public discourses. They intertwine, affect, antagonize, fold over themselves, and flee in different directions. Model for a Public Space [knot] is a seating formation which reflects this structure of discourse in its physical arrangement.

MPS [knot] is part of an international conference exploring the relationship between art and education, titled Extra-curricular: Between Art & Pedagogy. It will function as the site for a series of scheduled events and may be booked by any group interested in engaging in focused and non-hierarchical discussion.

Special Programming for MPS [knot]

Two conversations about love and politics in relation to contemporary art practices will be organized by Christine Shaw and Adrian Blackwell.

1. “Love is a force that acts as the productive motor of every emancipatory politics.”

Thursday, March 18, 2010, 7:00 pm

2. “Love is an event ignited by the distance between two polarities.”

Thursday, March 25, 2010, 7:00 pm

Love comes to compensate for the lack of a sexual connection. – Jacques Lacan

As parallel, yet separate, discourses, what common features do love and politics share? What is produced in the mismatch, or missed appointment, between the singular desires of individuals and communities? How are both intimate and political relations inevitably tied to the complex interactions between two bodies? This conversation will focus on the productive contradictions, antagonisms, and antinomies that underlie relations of politics and love.

Love and Politics Conversation 2 by Adrian Blackwell and Christine Shaw

Systole and Diastole

The subject of this conversation is driven by our observation that the relation between Art and Politics has been powerfully inflected in recent years by the political theory of philosophers such as Slavoj Zizek, Jacques Ranciere, Alain Badiou, and Chantal Mouffe.

As a group these theorists emphasize the confrontational dimension of politics. For each politics is a struggle between distinct and potentially conflicting ideologies: whether we think of Zizek’s concept of the parallax view, which suspends rather than reconciling the incompatibility of divergent viewpoints, Ranciere’s emphasis on disagreement as the essence of politics, Badiou’s focus on the non-connection between classes, or Mouffe’s concentration on the antagonistic and agonistic dimension of the political.

One of the common points of these diverse theories is a shared interest in the psychoanalytic theory of Jacques Lacan. Their collective focus on the importance of political non-connection is at least in part derived from his ideas.

Lacan himself did not often focus directly on the problem of politics in his work. Following from his return to Freud, he focused on the problem of the unconscious. For Lacan the reality of the unconscious is sexual and yet the truth of psychoanalysis is that “there is no such thing as a sexual relationship.”

At one level this means that our sexual relations are not with others, but with ourselves, they are internal to our own fantasies and desires. On the other hand for Lacan our deepest interiority is extimate, our unconscious is an Other, external to us, located in language, the structures of family, state, and the exchange relations of capitalism. So for Lacan our connections with a lover, are based on the one hand on the missed appointments, of our mismatched desires, and on the other, in the common tissues of the Others that envelope us.

Lacan used the word Love often in his seminars, but he maintained that “one cannot speak about it”. It was for him primarily an imaginary concept, not grounded in either our symbolic relations or in “the real.” He argued that all of our demands are fundamentally demands for love, but love comes to us only as compensation for the lack of a sexual relationship.

Through a sequence of lectures and texts called “What is Love or the Scene of the two” Alain Badiou has more recently extended Lacan’s theorization of Love. Although Badiou’s work on Love is a little difficult and obscure, I wanted to briefly introduce it here, in order to articulate some of our motivations behind these conversations. Unlike Hardt and Negri who we quoted as context for last week’s conversation Badiou argues that along with art and science, love and politics are distinct subjects for philosophy.

Badiou begins his discourse on Love from two of Lacan’s fundamental assertions:

1. There is no such thing as a sexual relationship

2. Love is a supplement to the lack of this relationship.

But for Badiou this supplement should not be seen as subsidiary to sex, rather he privileges love, arguing that love is the truth of sex.

Badiou recognizes that in love there must be something in common between two lovers, but in order that the truth of the non-connection is maintained this common term must be strictly minimal, and generic. Badiou calls this term “atomic”, a one-dimensional “point” of connectivity. This thing, that is common to each of the two, is indescribable, but he names this term “u” for universality, ubiquity and “un” (or one). U is the common cause of love for each of the two lovers.

But this minimal point in common does not forge a connection, so the two parts of the non-relation remain separate and crucially different from one another. The two lovers do not merge to form a totality; they remain a pure two.

This pure two, has two functions:

One is the inward movement towards “u” its common cause, an intimate movement towards one another, incredibly close, but never merging, or connecting, this two is intertwined and knotted in misunderstanding.

The other involves the subtraction or excision of “u” and the movement outwards into social and public situations seen from the point of view of the two. This is the presentation of love to others.

Badiou uses the beating of the heart as a metaphor for these two movements. The contraction of love towards the sexual and intimate lack of connection is called systole, while the expansion and excessive multiplication of love towards the world is called diastole. Systole and Diastole are the two movements of love. When love breaks down its difficulties can be found in one or both of these movements.

For Badiou, love is a specific event, one falls in love, which brings to light a universal truth. This event then demands a process of fidelity to its truth, a truth procedure which follows the systolic and diastolic movement of love from the bed to the world and back again.

The intersections of love and politics can both be seen through their separate yet parallel evental qualities. It seems to us that, in very different ways, the practices of the five presenters who are with us today, embrace this movement from the bed to the world…