January 11, 2018

Visions+la lumière collective, Montreal

Apucikam Megyunk Haza 8 minutes 2009

Beloved Village 4:11 minutes 2017

Now I Understand by Nicholas Kovats 4 minutes 2014

Field Niggas by Khalik Allah 60 minutes 2014

Nick intro

Nicholas Kovats. His friends, sometimes even folks who aren’t his friends, call him Nick. Let’s call him Nick. When he was 12 he saw 2001: A Space Odyssey, a movie he describes as a substantial virus. At 18 his next-door neighbour purchases a super 8 camera and when he sets eyes on it, he begins a lifelong obsession with small guage cameras, which he names camera systems. Some of his films were made with camera systems he has used exactly once.

He grew up in New Brunswick, and then came here to Montreal to study in Concordia where he majored in discrete mathmetics and digital engineering. In his final year he discovered there was something he loved more than numbers, and he started making films, “mini operas” featuring scantily clad men in leather doing terrible and vague things in post-apocalyptic warehouse buildings. Of course, he only shot in the winter. He fell in love, moved to Toronto, had a couple of kids, and became a bike courier. The culture of bikes and couriers is central to his making. He was part of the first Alleycat races that has since become a worldwide phenom, there were illegal road races where he would drive against the traffic in a pack, and then of course there was the legendary drinking and drugging which Nick was never part of but always around… the life-threatening injuries, the early deaths.

In 2003 he went to Sheridan College to become a telecom tech, got a real job, and with his new money began to buy and shoot film again. And of course more camera systems. He shot dozens of rolls that are still in his fridge waiting to be processed. Nick likes to talk about edge coding and ultra-pan 8, a wide-screen film format that has to be shot with a specially modified camera. There are only a dozen in the world, and of course Nick has one of them. But when you pry away the layers of technical distractions, Nick’s work is really an extension of the home movie, shot in home movie formats with family or friends, the camera work balletic, precise, most of the editing done on the fly, while shooting.

*

Apucikam Megyunk Haza (Papa we’re going home) shows the filmmaker returning to his native Hungary, and the villa his father bought in the 1960s, where the artist spent his childhood summers. This home movie travelogue uses the camera like a hand, lightly touching the swollen fruits, the ancient trees, the faces of his parents. The film bursts into colour as the artist visits his partner’s parents in the hills of Budapest, cutting wood, starting a cooking fire, inviting all for the potluck. Then it’s onto an old Communist train run by children in uniform, the camera forever moving, balletic and sensitive, opening.

Beloved Village opens with home movies made in communist Hungary showing a women’s school reunion, and interweaves them with a dancer in Toronto’s Trinity Bellwoods Park. The pull down claw is slightly out of register, so the dancer appears in a ghostly superimposition, the fragility of her movements and the medium itself underscored. Her actions are a memory rite, conjuring the women of another era, behind the iron curtain. The movie closes with a burst of fireworks, and then a suite of grainy family photographs, as a hissy fire sputters in the background, as if the past were being burned away to provide fuel for the urgencies of the present.

Now I Understand was shot in a single afternoon as a posse of former bike couriers meet up for an outdoors chowdown. As usual the camera moves gracefully across its subjects, looking for the opening faces, the hands waving, the feeling tone of conversation (without the words). We’re among friends here, and the camera is also a friend. A couple have become chicken farmers and a ritual slaughter caps the proceedings, hinting at the violence that underlies some of these relations. The movie closes with a quote from Anthelme Brillat-Savarin. “Tell me what you eat, and I’ll tell you what you are.”

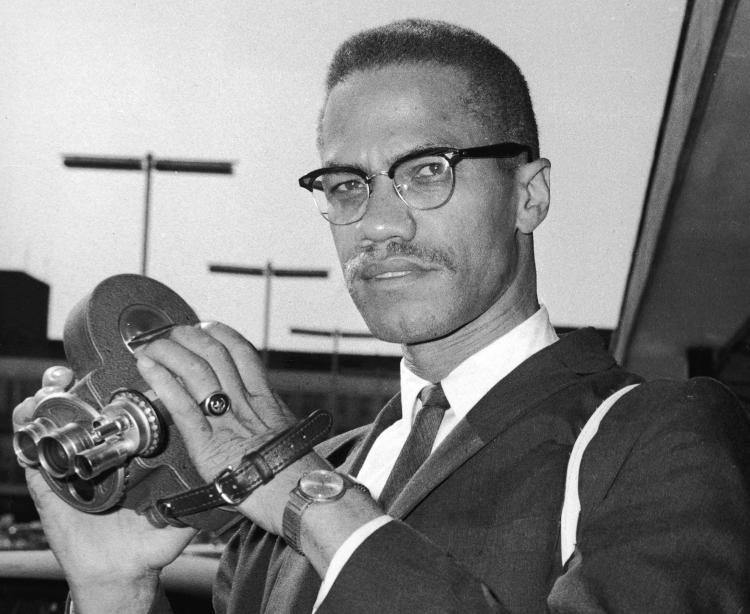

Field Niggas by Khalik Allah was the most important movie I saw in the past half dozen years. Impossibly, it was shot over the course of a few nights on the corner of 125th and Lexington Avenue in Harlem. It’s an updated version of cinema verité, a series of frank camera encounters, portraits of the underclass, always moving to get closer, to get up inside the grill of his subject comrades. As if the camera wanted to crawl inside them, so we could see what they see. Everything here is slow motion, and the sound doesn’t arrive at the same time as the picture, it was captured in a separate suite of chitchats, with the director chiming right in with his subjects, no need for any objectifying distances here. The folks he meets up with bear their wounds on their faces, their necks, their hands and voices. They are wasted and eloquent, hurt and flying. Drugs are a bassline, money, health care, mental health, housing, all that lives inside the steady stream. After the screening I saw, the artist talked about his pothead edit program, and the whole thing unfolds like a puff of nighttime hallucinations, the deeply saturated colours, those wounded eyes looking back. We are invited to join this intimate web, the “street opera” of pain and survival.

Malcolm X: The house Negro could afford to do that because he lived better than the field Negro. He ate better, he dressed better, and he lived in a better house. He lived right up next to his master – in the attic or the basement. He ate the same food his master ate and wore his same clothes. And he could talk just like his master – good diction. And he loved his master more than his master loved himself…

That was the house Negro. But then you had some field Negroes, who lived in huts, had nothing to lose. They wore the worst kind of clothes. They ate the worst food. And they caught hell. They felt the sting of the lash. They hated their master. Oh yes, they did. If the master got sick, they’d pray that the master died. If the master’s house caught afire, they’d pray for a strong wind to come along. This was the difference between the two.

And today you still have house Negroes and field Negroes. I’m a field Negro.