The Orientation Express by Frances Leeming

Eyeblink: Smash the Patriarchy (Younger Than Beyoncé Gallery, Pleasure Dome, Gardiner)

Gardiner Museum, Toronto, May 18, 2018

Let’s begin with a distinction too crude to be true. There are two kinds of artists. The first releases work as effortlessly as taking a shit each morning and announcing: look what I did! The second works their entire life on a single movie. In this science fiction plotting, Frances Leeming is the second kind of artist, and although she has made more than one movie, they are few and far between, not least because she has chosen the painstaking method of cut-out animation to say what cannot be said in words.

The Orientation Express (14 minutes 1987) begins with sound, honks and horns of traffic snarled in a jam, impatient for arrival. The act of listening, as the artist will demonstrate, is a political act. The first image offers the marquis of the Capital Theatre with the announcement: Romance And Adventure You Will Long Remember. Never mind the avant-garde, this is also an action movie. And then the artist slides in a personal note, a final line: I Know Where I Am Going.

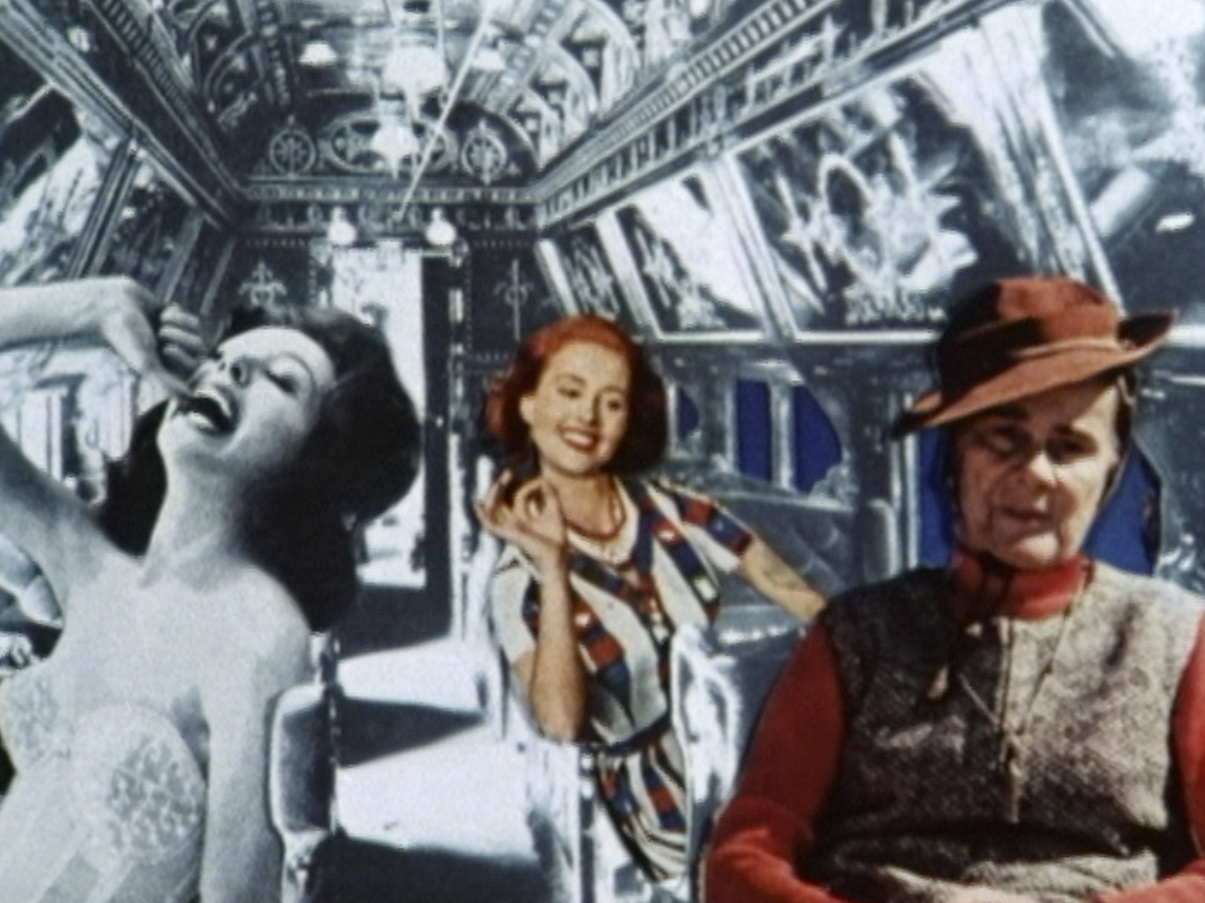

Many of the discrete episodes that make up The Orientation Express are recast as theatre/movie presentations before an audience of women, as if the double act of seeing and acting, of bearing witness and being seen (by women, undoing the seeing of men) were fundamental to these herstories.

After the prelude, the first scene brings us inside the theatre where an audience of women are gathered, and when the curtain parts we see Larry, the pilgrim face/logo from the Quaker Oats box. He tells his audience that his wife Rebecca is leaving him and the family, leaving for a train trip on the Orientation Express.

“Do you think that men even suspect that their definition of us and our experiences are only the definitions of a spectator?”

The second act brings us to the southern United States. Scarlett O’Hara throws in the towel, and then Colonel Sanders, KFC’s brand ambassador, pledges to protect “southern women’s virtue and chastity.” He is met by a feminist rejoinder that insists this is a cover story for slavery and economic exploitation. It should be noted that nearly all of the women and men are white, drawn from white media, commenting, or meta-commenting on white media creations.

The third act animates the Kool-Aid Man, the water pitcher mascot logo for Kool-Aid. He offers a vision of the suburbs, where zombie housewives, drunkenly preoccupied with self-help regimes, reimagine their man-partners as Jesus.

The fouth act shows clusters of world leaders, inevitably men, pointing fingers, or else huddled beside the machineries of war. A horse race propels the pictures, as if masculinity inevitably engaged competition, hierarchy, power. A slowed voice mouths misogynst slogans while a woman grants her assent, as the ironic tones of a muzaked Galveston ring out.

The fifth act returns to girlhood, where playtime creates shattered optics and multiple viewpoints. Later, in the workforce, forced to draw men’s shirts for a living, to copy the existing patriarchy in order to earn a wage, the narrator dreams her way into an escape, turning into a giantess midnight revenge creature.

The sixth act sees a country woman summoning bird familiars to restock the failing patriarchal government. Women rescue men from their fallings and drownings as Billie Holiday’s Crazy He Calls Me accompanies the repairs. A child, newly empowered, the progeny and consequence of these feminist re-orientations, speaks into the telephone, guiding activities and controlling the scenes until the tech glitches and she is left with her admiring audiences.