Gruppen Magazine, 2019

A contemporary Canadian filmmaker, Mike Hoolboom is one of those rare film activists who combines a flamboyant filmography with an impressive critical production. Born in 1959, he began making films in the early 80s, and was interested in promoting fringe cinema in the middle of the same decade, joining members of the Funnel and then working at the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Center. His commitment to Canadian production has resulted, among other things, in the publication of numerous books and catalogs highlighting the diversity and proliferation of this production (which is a little less well known than that of its American neighbor) as well as many programs since the mid-80s.

If Mike Hoolboom’s early films were relatively formal as he says in some interviews, he departed from this approach from the moment he thought he was going to die. In recent years resurgences of more structural work are appearing; as if to demonstrate that even this genre can be recuperated and returned to, only now with an urgent political messaging. See for example Beirut (2017), or even Visiting Hours (2018) which documents the visit of a woman to her husband in a prison (with footage derived from the Red Cross), that one can only think that it is about a Palestinian prisoner.

The particularity of Mike Hoolboom’s film work is that it fits, whatever the form used, in the shadow of a personal narrative, even if it is sometimes necessary to create biographies of artists, filmmakers or close friends.

Every book is part of a library, and inside that library there is a voice already waiting for you. And you won’t have to turn the last page of the last book before the promise of well-being and comfort issuing from that voices belongs to you.

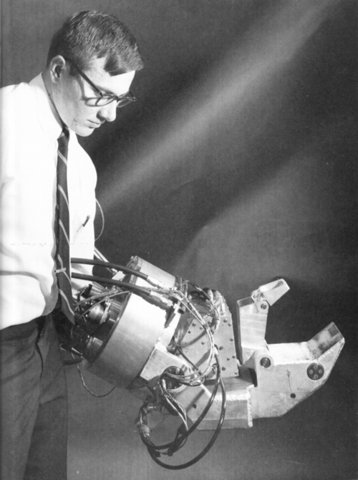

In any case, what is happening is above all narratives that explore the question of the survival of images in their relationship to oblivion and memory and that of an intimate or social point. These questions are addressed through the report that the production of images have with private and public bodies. This approach allows the filmmaker to free himself from the question of image authorship by leaning heavily on found footage: what is the necessary link between a biography and looted images? “We are the carriers of images, they inhabit us, like language, like a virus.” The body is a memory site of intimate social relations where it responds to a number of rules, codes and representations that produce us as much as we activate them. Film, video and digital reflections carry these concerns that more preponderant when he becomes his seropositivity. It is the articulation between perception – whether it is that of one’s own body or that of others – and the narrative (sound and voice) that shapes the work of the filmmaker. If at first the affirmation is above all personal, it steadily becomes more committed and political, questioning the invasive place of the media in our culture.

Mike’s filmography is important because it is in constant evolution. Some old 16mm films have been digitzed and included in larger ensemble texts like Panic Bodies (1998) and Imitations of Life (2004). Many are subject to a relentless and ongoing process of re-editing. For instance Tom (2002), the portrait of New York filmer Tom Chomont, was shown widely at a length of 75 minutes, but has now been trimmed to 53 minutes. We will limit ourselves for the purposes of this article to a few examples taken from the hundreds of films he has already made which will allow us to indicate some characteristics of his work.

It should be noted that the cinema in question, or more precisely the cinema that is directed, loved and defended by Mike Hoolboom is a marginal cinema, nearly in the sense that Jairo Ferreira speaking of cinema d’invenção (cinema of invention) about marginal productions at the end of the 60s and 70s, appropriating irreverently via quotation, parodying both the new wave and novo cinema. Apart from these specificities, the cinema that Mike Hoolboom produces and defends is made up of small movies, distant echoes of these men without quality of which Robert Musil spoke, but also contemporary with the cinema of small gestures preached by Derek Jarman with his super 8 filmed newspapers. These little films are actually the cinema itself; they allow us to implement what the cinema should always allow, that is to say, the constitution of meaning by the spectators from an experience that can sometimes be heroic (we then think of the six hours of Sleep, (1964) or the three hours of La Region Centrale (1971) by Michael Snow, or more simply at the Impatience (1928) induced by the variations and permutations of the sequences of the film of the same name by Charles Dekekeulaire. The film’s experience is exemplary in that it shapes us as much as it allows us to create the film.

Here is the common secret of artists film and video: that every spectator is also an artist, a creator. And each marginal film shares, to a greater or lesser degree, this utopian hope: that it can provide the moment (through boredom, or rigor, or an impossible color) that will transform its audience into artists.

For Mike Hoolboom the experience of the film is above all a collective experience, the transformation of “us” in a shared moment. For that reason he has for several years been having difficulties with installations or films in galleries or museums. On the other hand, the dominant form that has become the film festival is hardly better because their programming often responds to forms that harm these small films. Another difficulty of these films comes from the fact that their scarcity leads us to see them at times that are not necessarily the best. So the activity of seeing movies is related to making movies, for Mike Hoolboom. This explains his investment in programming venues in Toronto and beyond, as much as his writing and interviews with many filmmakers and video artists for over 30 years.

His cinematographic work moves through different genres of cinema ranging from filmed diaries to biographies and essays. But the categories are easily mixed. Films around the issue of AIDS have formed for nearly 30 years an important axis that take different forms depending on the nature of the projects. But these films do not exhaust the possibilities of an impossible future. At first, they register mourning as a particular mixture between a past re/de-composed and a present which is both ours and public. The recollections at work in Frank’s Cock (1993) and in Dear Madonna (1996) and Hey Madonna (1999) shatter the limits of a subject in favor of the social implications of the epidemic. In one case the story of a relationship suffering the consequences of AIDS is evoked by a figure who delivers a funny and moving story of his relationship to his lover Frank. Letters from Home (1996) summons a set of testimonials on AIDS inspired by a speech from Vito Russo who said that we all live with AIDS whether we have it or not.

Buffalo Death Mask (2013) features two survivors conversing on new medications and reminiscing about missing friends, wondering why they are still alive. The use of handwritten titles before the introduction of dialogue is an important element of the narrative because it prepares our future listening. Mike Hoolboom holds a special place for the voice, it can be a dominant element.

In all these films the intertwining of cinematographic documents and their juxtaposition deploy kaleidoscopic effects. This is most strongly asserted in Frank’s Cock because of the division of the screen into four distinct fields. We find this four-screen division and arrangement of multiple points of view again in Positiv (1998) in which the narrator is in the upper right corner. This film is part of the afterlife, of that time that the artist was not supposed to live.

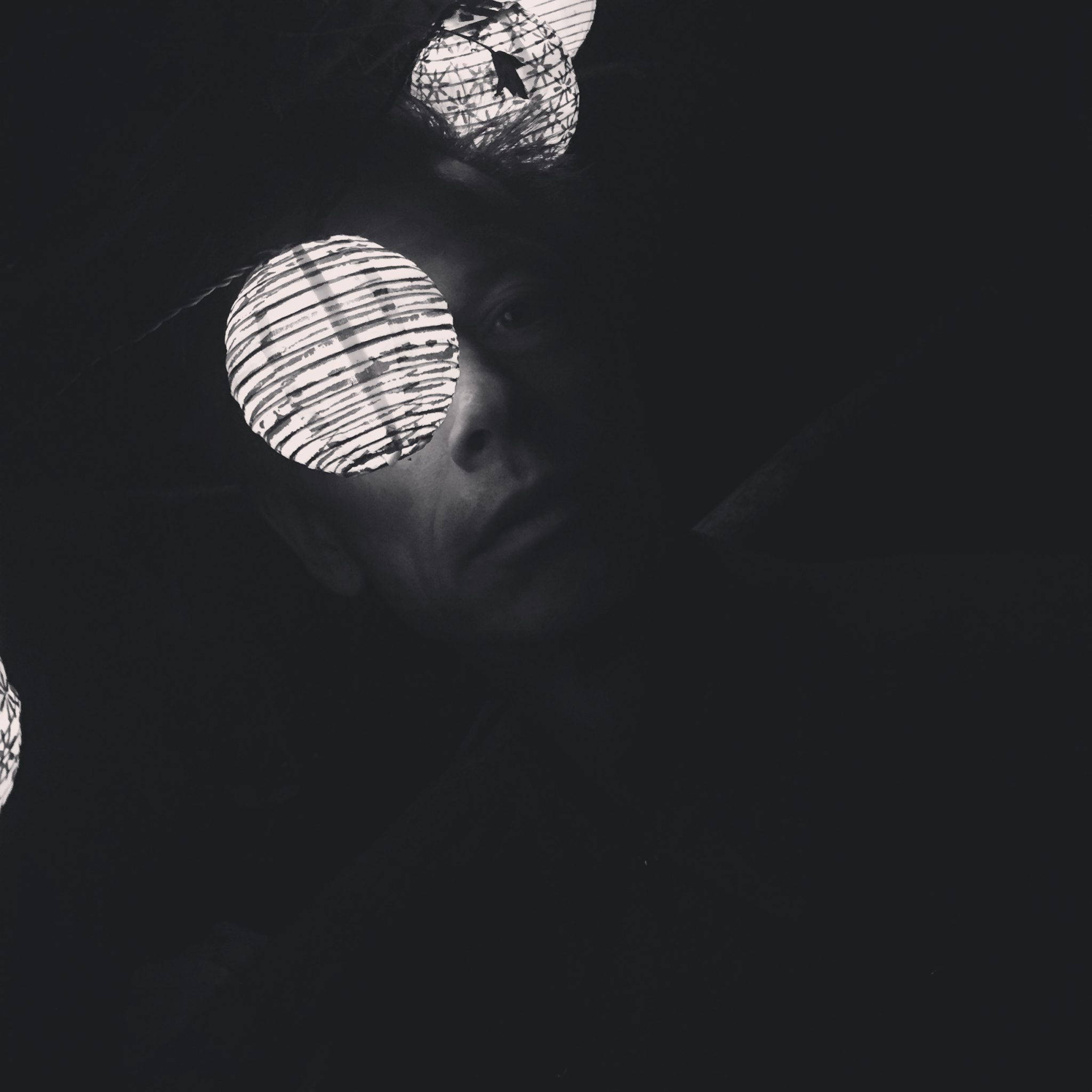

In Buffalo Death Mask and in most of Mike Hoolboom’s films, the rhythm of the sequences is relatively slow, they appear in a state of suspension, filled with ghostly presences. Some scenes are drawn from Mike’s archives where we can see the mark of opportunistic diseases (shingles), while other images belonged to earlier films, before they were recycled and treated differently. Winks from other times come to haunt the images of the present. Irruption by splinters of incandescences, a face, a person arises in the light to better disappear in the flicker.

The sequences intermingle via superposition or as a result of jerky melting or intertwined according to complementary chromatic pulsations. The images do not illustrate the conversation between friends, they seem to respond to a particular logic that may be that of a certain familiarity, or a disturbing strangeness, or distant echoes of some Hollywood movies or newsreels. Their surge reminds us that we have been formed by them. That’s what Matthias Mueller rightly notes about Mike Hoolboom’s film work: Hoolboom knows that memory can never be condensed into a single image, it’s always a complex mix of past and present, of what is our own and of what we are appropriated by, or find appropriate: facts and fictions. His work does not revolve around a specific isolated subject; it revolves around the totality (and totalitarianism) of our global synchronized image world. Newly homeless in his hands, the images gather in groups and generate complex, almost crystalline structures. At one time or another we have seen these images and they have likely modeled us. They might reappear at any time. The film proceeds to collect them in an act of temporary community building, recalling pictures that we are forced to see (how to avoid them?), in the ongoing collage of computer culture or city strolls. From this understanding we see the links between spectacular alienation and film production; cinema becomes the most active agent in structuring and modeling behaviours. They conjure temporalities that sometimes transcend time.

When this narrative striptease is rendered, when the films are constructed as a digression or as an open field in which the audience is invited to wander, it is possible to leave the theater with profoundly different experiences.

Here we see a possible convergence in Mike Hoolboom’s analysis with those defended at the same time and in different ways by Guy Debord on one side and Al Razutis on the other. “Your new world will begin like ours with images that we aspire to see, cherish and become. We are already plundering our world of images, incapable of invention, we are reviving the dead modes transforming the past into a history of styles.”

However, Mike Hoolboom’s difference lies in the dreamlike and poetic dimensions of these analytics and narratives that can be read or heard in his various films, and which each time introduce us to a world close to his disappearance, even as it summons an abundance, a rich overflow. Images pour out in front of our never satiated pupils. The film becomes an instrument that allows us to think not only about the history of cinema, but especially what these stories have done to us, how our lives are a kind of reaction shot. The cinema mobilizes us. Our perceptions call us via a double movement of introspection and avoidance.

In Imitation of Life, (the section of the film that gives the name to the entire movie) the reflection on the future of the film image is questioned according to our insatiable appetite to absorb images: always, we want more. Intertitles announce: “Films mark the passage of time. They are time machines, machines built for mourning and at times they are all that separates us from our desire to destroy everything… There are two kinds of terror here. The terror of annihilation and the terror of memory. Which will be more painful, more seductive? How will you invent the future?”

Each film is thus from its first image a jump into a distinct and yet familiar universe. The relationship between sounds and images is dynamic, sound clips as well as sequences of images are distributed according to arrangements that give them new meanings. The music of advertising campaigns as much as the images they pack, are accompanied by the voice of a child in Imitation of Life, describing a morbid world in which “We cannot imagine the future, we forget the past. You do not have an ecology of time. Your memory is our forgetting. The unborn will walk on your graves as if you had never lived. And when you leave this place there will be no one left to mourn you.”

The musical sounds summon atmospheres from which a voice is raised. The work of the film is elaborated by overlapping and successive layers that come into focus via unexpected juxtapositions.

The first sequences of Imitation of Life are exemplary regarding the strategies used to reinvigorate images so often seen. Slow motion and editing grant a new dynamic to these rehearsed shots, so they can carry other meanings.

We are literally immersed in an audio-visual world that appeals to the entire history of cinema. These bursts of cinema are reflections of a world constituted by images of an imagined future. In any case, they offer earlier futures that are sometimes the mark of the cinema of found footage. Mike Hoolboom recreates a present world from images made previously. It is a question now of returning to a future that his AIDS diagnosis refused. Today this future reappears as pure science fiction. It blossoms in telescoping plans of a disappearing city, the appearance and dissolution of bodies, the accumulation of hands. Voices of a man and a woman separately intervene. The images, sounds and intertitles intertwine to create a new time of remembrance, which is none other than that of a future which inscribes its return in a nostalgia to come.

We live and take shape inside images of intense proximity whose strangeness can disturb and even destablilize us. Our image, is it really ours? Or is it only a tacit agreement that we grant temporarily. This is subtly revealed by the voice-over of Scrapbook (2015), which tells the story of Donna Washington, a daring autist, who discovers fifty years later the images of one of her previous selves. The encounter with these images is at the same time a discovery of a self which never was. She became “herself” only by recognizing herself as someone else – Otherness as a healing mode of perception.

Kim was someone I met at the Center. I did not understand it was me, I thought she was another person. She was the first one I experienced as a totally separate person. I said, it’s Kim. And then I decided that I would become this image, this image of Kim. I would become everything people would want, whatever they want.

“She would learn how to look by watching the others. I think we were all watching each other very closely. And then, after I became a picture, I could let someone like me, and be my friend.

Is Donna’s experience so far from ours in terms of the shaping or modeling that we experience through the media? By contrasting images that populate us, Mike Hoolboom create interrogations through subtle fictions that allow us to question again the relationship we have with them, knowing that one of the only ways we have to oppose it is to propose other uses. This is precisely what Mike Hoolboom knows so well, giving images a special touch, close to a new skin.