Il Manifesto (quotidiano communista), November 23, 2019

Filmmaker Mike Hoolboom received the New Visions Award at the Festival Efebo D’Oro in Palermo, accompanying his retrospective. He also presented a retrospective of his work at Milan’s Filmmaker Festival that combines experimentation, autobiography and documentary. He is one of Canada’s most significant experimental filmmakers, and at 60 has made over a hundred shorts and features. Born in 1949 in Toronto, Mike Hoolboom began working in super 8 in the 1980s, processing material with great originality and with considerable editing skills which has made found footage nearly indistinguishable from material generated by the artist himself.

In his cinema the documentary approach merges with the autobiographical one, producing highly saturated imagery in which layered images are reinforced by the use of voiceover and overlaid texts. All this makes each of his works full of visual/verbal associations and meanings, with decidedly political markings. Moreover, the fact that he has a Dutch father and an Indonesian mother has certainly influenced his multicultural expressions.

Thirty years ago, after discovering that he was HIV positive, there was a radical change in the life of the artist, a radical rethink of aesthetics (form) and contents, such as the question of the future posed in Imitations of Life (2002), but above all, putting the body at the center of his work. Here was a newly porous body, of blood and tissues and viruses, caught inside the prison house of language, newly cyborg and metamorphic (raising the question of gender identity), but also cinematic, living in relation to the body’s many representations and projections. Here were new bodies suspended between perception and memory.

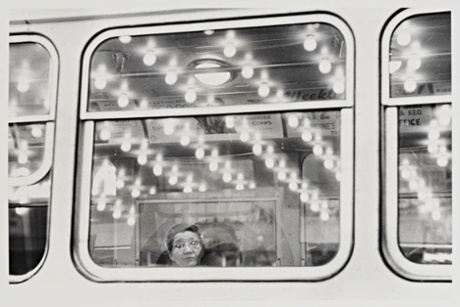

Hoolboom named his University of Palermo master class on October 18, 2019: Throwing the Body. He was in Palermo as a guest of the festival, presenting three features: Father Auditions (2019), Aftermath (2018), and Public Lighting (2004-revised in 2015). Aftermath offers a suite of mini-portraits of Fats Waller, Jackson Pollock, Janieta Eyre and Frida Kahlo. It is a work of great poetic intensity where the biographical starting point and analysis of their creative process is just a pretext to investigate the cultural, social, psychoanalytic and anthropological questions related to the four artists.

While Hoolboom’s cinema is linked to the tradition of the classical underground, with references to homo-eroticism (think of Kenneth Anger’s Fireworks), with a dreamlike, surrealist and visionary style, researching the graininess of the film on one hand, while being perfectly comfortable in the age of digital images – taking images from Hollywood commercials, music videos and obscure film exercises, the director explores the opposite aesthetic: glamorous and seductive, activating a critical reflection on mainstream media imagery. Found footage in Hoolboom’s work, however, is always understood as a charged, almost talismanic fragment of a past that continues to reverberate in the present. Always reluctant to leave his Toronto apartment, Hoolboom took advantage of this Italian trip to present his films also to the Milanese public, as a guest of the Filmmaker Festival that is being held from 15 to 24 November, 2019.

Bruno: I would like to begin by asking you if you have a relationship with the context of Canadian experimental cinema, which, even today, seems very vital to me.

Mike: Many of my friends are movie artists, and we exchange blunt opinions, sparing each other nothing. We are in constant contact over many years already, it is impossible to imagine working without them. My work requires triangulation, a third figure, that is neither artist nor film, and friendship enters into this gap. Most recently the sage artists Alexandra Gelis and Jorge Lozano have moved into my artist’s co-op, and we see each other almost daily. They are mostly unknown abroad because of their indifference to distribution, but their work, centering people-of-colour, immigrants and outsiders, is central to rethinking the traditions of fringe cinema.

Bruno: Your filmography is boundless, where does this need to be so prolific come from?

Mike: Why keep making movies when there are already too many? Filming is a way to metabolize conversations, meetings, ideas. The real answer is pleasure. We have been delivered to a technological utopia, with mixing studio, editing bench, and film lab collapsed into a free (!) software program with enormous flexibility. There has never been a better time to make movies, though distribution is dire.

I should add that my body of work is always in progress. A digital work is never finished. Six years ago I began going through all of my work again, recutting everything. I felt them calling for attention, which I was happy to grant. And of course I throw away many movies. My hope remains that my filmography will shrink as I grow older. For anyone who is interested, most are available on my Vimeo channel.

Bruno: Some of your works such as Public Lighting and Imitations of Life are divided into different parts: where does the need to build feature films made up of short films with their own autonomy arise?

Mike: When a friendship deepens you meet them in moments of tragedy and distress and also great joy and easygoing deliriums. How to show the so many faces that live in one face? Even our bodies are changing genders, switching from top to bottom and back again, changing size. And each day is a series of time travelling cuts via the internet, the phone, and then a sudden encounter in the apartment lobby. This postmodern collage of surfaces and meetings might require the reflection of a long form cut-up.

Bruno: I find it very interesting how you use ‘found footage’ as part of a discourse of criticism and analysis of the mass media and society. In short, you make “political” use of it, a bit like Guy Debord’s “détournement.”

Mike: Yes to the turn, the turning. It’s a question of movement, how to make these pictures move again, how to let our bodies move again, instead of being stuck in the old rules and roles. Many mainstream clips and films are so insistent that it’s nearly impossible not to see them, this mediascape is my landscape, it’s already part of me, so I don’t feel I’m taking something from “out there,” but working with material that is already “in here.” Using these materials can be helpful to show how old hierarchies and social groups can be subverted and transformed; they can flow in a newly imagined space where new kinds of sexuality can be celebrated, along with new bodies, new vectors of belonging. How can we change our lives if we can’t change the pictures that surround us? How can we really intervene in our climate catastrophe except with images that offer a counter-narrative to the oil oligarchies? The boat trip of Greta Thunberg, to name just one example, was a powerful picture that sailed all over the world.

Bruno: Your interest in media criticism then results in work on pop culture icons. I’m thinking of your short movie Hey Madonna (2004), which is one of the chapters of Public Lighting, as well as existing as a stand-alone short.

Mike: In my modest footnote of a remake, Madonna/David Fincher’s brilliant subculture borrowings are refashioned as a fan letter, audio-visual graffiti is scribbled across their glossy picture texts. When we were dying of AIDS we were also “dancing to the music,” and “striking a pose,” though unlike her blondness we were not interested in manufacturing consent, but creating dissonance. We wanted to celebrate the awkward and imperfect. Every day was the end of the world.

Bruno: However, you also use stock images from a more autobiographical perspective. How do they combine with each other?

Mike: My work in “video” began with a series of found footage portraits, collapsing two apparently incompatible genres. But wait. How could you argue that an image that we have never seen or experienced can really represent us? How can you stuff the body of a living subject with found footages and suggest: this is a portrait?

My parents lived through nameless traumas during the Second World War. My mother was Indonesian and grew up during the Japanese occupation. My father’s father was taken to a concentration camp, while he hunched low at his school desk so the German soldiers wouldn’t pick him up for “work duty.” There were years of privation and violence. The reality of these undigested horrors remain my central experiences and memory, they have become the frame through which I understand the world. My body is made up of these pictures, I myself am found footage. Working in video allowed me to explore these questions of copying, displacement, trauma, war and power.

Bruno: Your cinema is very much spoken, you feel the need to build, through the word, a narrative level to make sense of images. Let’s say to create multiple meanings.

Mike: In English we have this expression: “mother tongue.” As if we were always speaking from, or speaking to, our mothers. How did Barthes put it? When you offer a gift, you are always dishing it to your mother. Language is not always a gift of course, it can also be a threat, an arena of power and intimacy.

Bruno: The relationship between the physical-biological body and media representation is also very strong in your films. Here in Palermo you have held a master class on this very topic. Can you explain how it unfolded?

Mike: We began with action. Perhaps the cinema should begin with the word “action.” While one partner wore a blindfold, the other created a film using only sounds and touch. It was a way to resist the dominant frame of the education system, which insists that we have no bodies. Our schools say yes to the mind and no to the body, as if there were a difference between the two.

During the workshop the student comrades listened with their whole bodies, and most importantly, each of them learned where fear lives in their body. And with the help of a comrade, they could survive this fear (some were put on bicycles), and come out the other side. When we were no longer blind, we listened to each other testify, we granted attention to every person in the class, as if we were living in a democracy.

Bruno: Is there a particularly logical and rational method in associating images, symbols, quotations or, on the contrary, you are guided by instinct, flow logic?

Mike: The most important moments in my life are a mystery. Why is my best friend my best friend? Why did I fall in love with that person? How to create a movie that makes room for this place of not knowing, this fundamental mystery at the heart of things, what some have named “the unconscious?”

Here in Palermo I’ve begun working on a movie, gathering faces mostly, in extreme close ups, as well as graffiti. Where will these faces summon me, what road will they insist on taking? I am prepared to follow them, wherever they might lead.

Bruno: Another aspect of your aesthetic that interests me a lot is the mixture you create between documentary and experimentation. I think of your beautiful Mexico (1992) made with Steve Sanguedolce.

Mike: We drove across North America, from Toronto to Mexico City and beyond, shooting 16mm Kodachrome along the way, without a sense of purpose or direction. It took us four years to give that material a shape, which finally appeared as a series of moving postcards with a voice-over, with a fictional narrator/traveller, a stand-in for us, who eventually confuses Mexico with Toronto. Many thoughts about the new “free trade” agreement were laid in alongside poetic reveries and asides. We proclaimed our faith in digression, but didn’t hesitate to make salient political critiques along the way.

Bruno: Can we consider your daily practice of filming an extension of Mekas’ diaristic cinema?

Mike: Mekas’s cinema is an open-hearted, nomadic cinema. As an exile he is forever recreating communities, his movies are documents of loneliness, displacement, migration, temporary pleasures, the joys of friends. Because he lived in the maelstrom that was New York City, his work arrives in a rush, a flurry of impressions and images. For me, I still live in the city where I was born. Walter Benjamin wrote there are two kinds of storytellers: the ones who travel, bringing stories from one place to another, and the ones who stay in the same place all their lives.

Bruno: Could we call you a surrealist movie avatar? Both for the obvious quotes in your films, and for the dreamlike and strongly psychoanalytic dimensions that you recreate?

Mike: Surrealist cinema poses questions that can’t be answered. Answers are a way of throwing away or dismissing questions. Good questions are enduring, productive, generative even. How can we find our way, how can we arrive at the place we most fear and most want to arrive at, unless we get thoroughly lost?

Bruno: How much has your cinema (and your look at reality) changed since you found out you were HIV positive?

Mike: What didn’t change? So many of us died, or else we watched each other die. There was a new urgency after receiving the diagnosis, which was a death sentence then, and it required a new way of making cinema, not only of making political work but of making work politically.

Bruno: You have made many movies on the subject of AIDS, including Eternity (1996), A Boy’s Life (1996-2018) and Frank’s Cock. For me the latter is a traditionally dramatic love story, tragic because Frank dies in the end, though the lover’s feeling endures. Positiv (1998) borrows the four-screen format of Frank’s Cock, though this time you are the narrator, offering a confession-essay about the illness. Its many screens brings to mind the possibility of proposing the film as a four-screen installation.

Mike: My work has sometimes taken the form of installations in galleries and museums. It’s a rare privilege, a happy consequence. Though mostly I find contemporary art bewildering, I am more deeply engaged in conversations with books and movies.

Bruno: Are your films funded by the Canadian state?

Mike: Only occasionally. There is funding available from the country, the province and the city, though most of my movies cost nothing, and are self-funded. I try to spend as little as money as possible, because I need time to work. I have no institutional support, it’s a precarious balance between eating peanut butter sandwiches for months, and operating in a temporary luxury where I am able to buy a new lens or even shoot super 8 again.

Bruno: Today, in addition to using digital cameras, do you continue to shoot some sequences in super 8 like you did in the beginning?

Mike: I’m just finishing an hour-long portrait of my pal Judy Rebick, iconic second wave feminist who led the charge for women’s right to choose (abortion rights), amongst many other struggles. It was all shot on super 8, as a reflection and embodiment of that time, we hoped to reframe the movie’s time machine with ancient chemistries.

Bruno: How much has your approach to images changed with the transition from analog to digital?

Mike: Film is production, digital cinema is postproduction. Film retains its siren call of silvery fetishism, along with its snobby elitism. I regularly vote for upcycling, reusing pictures, even if they are only my newly lensed attempts. In the digital world I begin with every image and then I make a selection, a choice. It’s a question of ethics. Of how we belong with each other.

Bruno: What is cinema for you?

Mike: I’ve seen many ways of making busy being born and then dying. What’s unfortunate is the way that hyper-formalist concerns, what I regard as “conservative” in the sense of conserving something, holding onto the past – remains central to the understanding of artist’s movies. I just don’t understand why the work isn’t stranger, weirder, instead of becoming a genre that persistently celebrates whiteness and white histories.

Labouring under neo-liberal regimes of hyper capitalism impels us towards new forms of community and solitude, and all this might be accompanied with new forms of cinema. These movie time capsules are also a memento mori, grieving machines, so that we can hear and live again inside the forgotten and repressed and left behind stories that will help us with the resistances required today.