Yves Tremblay: For how long have you known Judy, have you both been friends?

Mike: Ten years. We met at a New Year’s Eve party hosted by our mutual friend Velcrow who read our tarot cards. Even though we had just met, it seemed there was already a shared future waiting. Judy has a laugh that embraces everyone in the room like a warm hug.

Yves: When and how did you get the idea of a movie about her?

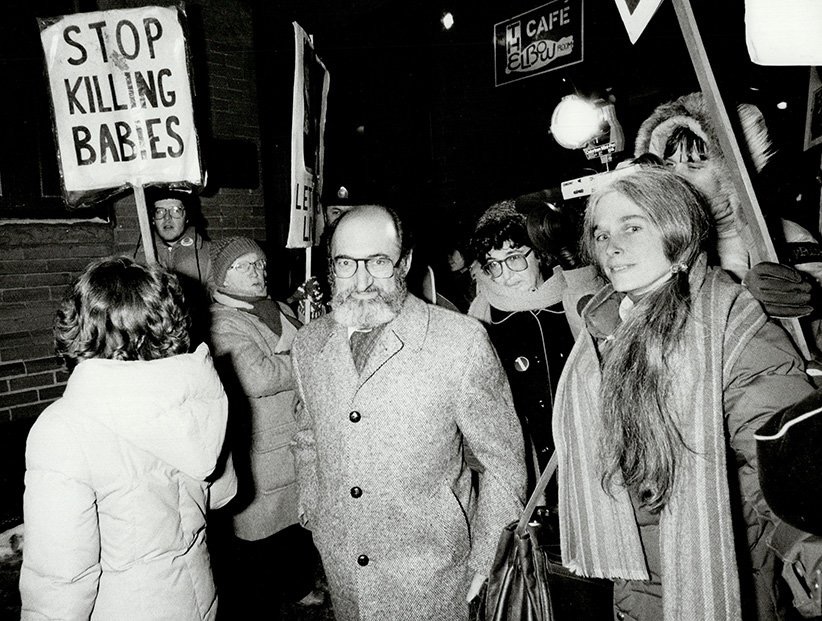

Mike: It’s hard to believe there isn’t at least a mini-series about Judy already, she’s lived a hundred lives. The Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane stayed at her hippie crash pad in Montreal, she sold t-shirts to Jimi Hendrix in the village in New York before travelling round the world by herself. But mostly she’s dedicated her life to helping others, and she’s done it by becoming part of so many movements. How do you make a picture of a movement? And how to recall that terrifying time in the 80s when Christian activists were on the streets every day shouting abuse and threatening women who wanted to make their own medical decisions about their own bodies? The abortion struggle was so intense, the clinic was bombed by professionals, something that just doesn’t happen in this country. It’s a story that needed to be told, and Judy was at the heart of it all, and remains a consummate storyteller.

Yves: It’s a wonderfully intimate and revealing documentary about Judy Rebick. How many interviews, or meetings did you record with her? Did you have a precise plan of the progression happening in the movie? Did you plan together the subjects she talks about or did it happen spontaneously, freely?

Mike: I’m not a big believer in maps and plans. I don’t have a mobile phone so I’m forever getting lost, which means going somewhere you don’t know. Bookstores are also helpful for this, they offer the unimaginable, they present what I didn’t know I needed.

I’ve made many portraits over the past four decades, of my pal Tom who died of AIDS, or my animal-rights activist friend Mark Karbusicky, and many others.

I’ve been making movies since 1980 but never with talking heads, so when Judy and I spoke “on the record” it was audio only. I think we taped four sessions, a couple of them very short, just over a couple of hours in total. Judy is a walking sound bite machine of course, there was no need for more. Her recall is exact and her phrasings camera ready. I arrived unprepared as usual, I guess I saw our conversation as an extension of chitcahts we were already having.

Yves: You are a very prolific director. Is it the first time you’re doing a portrait of a person? Also, did you decide from the beginning that there would be a «voice over» from Judy, with various images and 16mm excerpts along with it? It’s very interesting and original form indeed… Why did you choose that way? When did you find the title and also the idea of different chapters, the themes, and their progression from intimate to political?

Mike: After many months I completed a definitive edit. That was the fantasy. It was delivered to friends who assured me that the movie was incoherent, unwatchable, confused. After receiving the news I lay in bed paralyzed. When I got up days later I started working on short takes, movies that offered only minor heartbreaks. It was obvious that I had failed my friend, not to mention the project, which as I understand it, lives entirely separately from me. My job was to offer whatever was required, which I didn’t manage.

Time passed. I had energy in my body again. I saw Judy many times and we never spoke about the movie, which was merciful. One night, almost asleep, a stray thought arrived written by strangers. The movie doesn’t have to be a smooth ride, it could be broken up into chapters. What could be at the head of each chapter? Perhaps Judy speaking in public, she’s so different when she’s up in front of a crowd. She becomes “Judy Rebick.” As her alters (her different personalties) say about one of her boyfriends: “He only likes ‘Judy Rebick.’” The public figure. The street fighter. The lightning rod feeding the crowd’s energy back to itself.

The title, like the structure of the movie, arrived out of failure. The movie was initially called “Judy,” but my film reviewer friends told me that the version they watched was not about Judy. Simply put: the film’s title raised unfulfilled expectations. I was starting a series of movies about capitalism, so I thought Judy versus Capitalism carried a ring. One of Judy’s friends heard the title and said: J vs C? My money’s on Judy!

Yves: Did you work on the movie during the first wave of the pandemic? If so, did that help you (to concentrate on the work, maybe) or was it a greater challenge?

Mike: The movie was finished just as the pandemic was beginning in Asia. We premiered it at the Rotterdam Festival at the end of January. As usual last minute surgeries were required just before the festival. A few weeks later the whole world changed.

Yves: How long did you work on editing? It looks like a colossal piece of work! What was the main challenge and also maybe the greatest pleasure about it?

Mike: It took over a year, but I worked in luxury. For instance, my commute means walking one flight of stairs from bedroom to main floor where my computer God is waiting for further attention. I love to edit, it’s entirely satisfying. I don’t think I’ve gone more than a few days over the past few decades, without editing. Judy’s voice was always a reliable guide. No matter how far off the beam I wandered, there was always her voice, bringing us back to the lived urgencies, the university occupation, the pro-Palestine demo, the Indigenous solidarity walk.

Yves: You create real soundscapes in your films, giving them an experimental and emotional aspect. It includes different noises, sounds of nature and people, mixed with «concrete» sounds… How do you proceed in creating these? Where do you take and/or capture them? Do you create them after the image’s editing, at the same time?…back and forth?…

Mike: I spent ten years in a Zen cult learning how to listen. After days of silence, the sound of leaves rubbing together, or the aching drone of a passing car is sweetness itself. I began a recording practice, working with small cheap gear, and then started collecting tracks from others who were similarly devoted.

Yves: There are many very special moments in the film, from my point of view. For instance the times when Judy is talking to the crowd in some demonstrations, and also the slow motion of an attack against Morgentaler, where Judy intervenes. How did you chose these intense and meaningful moments? Were they obvious or hard to chose? What guides you to highlight certain actions she did, compare to others?

Mike: Buddhists say that some actions are written on water, some on sand, others on stone. But a life-changing event—written in stone—might last just a fraction of a second. On the day the abortion clinic opened, Judy escorted Dr. Morgentaler to the front door in front of a battery of cameras. A man rushed out of the crowd and tried to kill the doctor. In slow motion you can clearly see that Judy acts without hesitation, she steps right in front of this guy and stops the attack, even though he wields a threatening pair of garden shears. Owing to the profusion of cameras she became a public figure overnight (though she had worked as an activist for decades before this). It’s such a clear demonstration of public courage. Putting your body on the line for what you believe in. Though it’s hard to fathom in “real time,” where the blur of actions turn into fiction. In order to restore documentary, the footage needed to be slowed down.

Yves: Did you think at first this homage to Judy would get at times deep into psychology, or was it a surprise? It’s incredibly strong as a portrait anyhow, showing all this delicate material, bravo!

Mike: We’re friends and hang out all the time, so I think it would have been strange if we hadn’t discussed personal matters. While writing her memoir, she decided to speak frankly about her sexual abuse, and the multiple personalities she developed (unconsciously of course) in order to survive it. She describes this as a creative act, a genius moment of artmaking that only a child could conjure—which is a very different reading than being tagged “mentally ill.” It’s a startling and empowering reframing.

Yves: The movie has been screened in many festivals since January 2020, but mostly during the pandemic. Are there any advantages of that fact, besides all the bad sides of it?

Mike: It means I don’t have to travel, which is great, I’m not big on airports. But Judy’s pretty disappointed, she’s so good in front of a crowd, it would have been so fine to have that opportunity.

I think the pandemic has offered new ways to take care of each other, as well as a chance to reflect on what is necessary, fundamental even. Where do I feel safe? Where did I learn the most important things in my life (ie. what is education)? How can I have a conversation with people I completely disagree with (Judy is a genius at this)? Perhaps the movie offers a small nudge in this direction, though whenever I go online I am met by a deluge.

Yves: What are your next project(s)?

Mike: I’m working on a series of movies about capitalism. I’d like to make a kind of adaptation or translation of Silvia Federici’s groundbreaking tract Caliban and the Witch. As a feminist historian, she returns to the origins of capitalism and finds that there were two things that made it possible. The first is the theft of “the commons” (what we might call public property, or things we all share)—back in the day that meant land, today it still means land, but also water, computer clicks, our geographical locations—all that is still being stolen and turned into commodities. As Federici states: capitalism returns to its origins again and again, converting what is publically held into “primitive accumulation” (Marx’s term) for a few.

The second thing that made capitalism possible was the persecution of women. It was known as the witchhunt and went on for two centuries. All of the major power players: church, state and aristocracy, conspired to systematically torture and execute hundreds of thousands of women. Many fought back of course, and many are still fighting back. Judy is one of their number, part of a long line we can’t afford to forget.