Jihlava International Film Festival, October 29, 2020

Andrea Slovakova: There are so many layers of meanings I would like to discuss with you. Every time I watched Touch Memory (14:30 minutes, 2020) I discovered new formal elements, especially in the audio, that I could add to its puzzle of meanings. There is a strong personal level about your father, but also, as in many of your films, a broader social level where you raise questions about how society is structured and how institutions work. Can you tell me how your father is connected with Vietnam? As the film says: “I didn’t just lose my father. I lost Vietnam.”

Mike: It’s the father of the film’s co-maker Josephine Bérthiou, not mine. I live in Canada, a country of immigrants. The only people who really belong here are Indigenous, but we did what most settler colonists managed, which is to murder or marginalize them. After a period of strictly white rule, people came from every country in the world to live here. My sister, who looks more like my part-Indonesian mother than I, was challenged at grade school, assumed to have a connection with distant exotic countries, only she doesn’t. She was born in Canada, doesn’t speak Indonesian, has no relation with that culture. It raises question about continuity and rupture. Why did my mother move, and how was she encouraged/threatened to erase her past to fit into the dominant white culture here? Citizenship is a frame that says yes to certain people, behaviours, even skin colours. And there is also resistance to that, via cultural initiatives, alternative schools, neighbours and friendships. You use the word ‘puzzle.’ For many of us identity remains a puzzle.

Andrea: In the film, the father says that memory is a second chance. This touches on the question of identity. People with diverse backgrounds are often asked to reinvent their identities, to assimilate.

Manthia Diawara: What does departure mean for you?

Edouard Glissant: It’s the moment when one consents not to be a single being and attempts to be many beings at the same time. In other words, for me every diaspora is the passage from unity to multiplicity. Let us not forget that Africa has been the source of all kinds of diasporas—not only the forced diaspora imposed by the West through the slave trade, but also of millions of all types of diasporas before—that have populated the world. One of Africa’s vocations is to be a kind of foundational unity which develops and transforms into a diversity. And it seems to me that, if we don’t think about that properly, we won’t be able to understand what we ourselves can do, as participants in this African diaspora, to help the world to realize its true self, in other words its multiplicity, and to respect itself as such.

Andrea: The overall rhythm is captivating, it brings me inside the film, many shots arrive in slow motion but at different speeds. One of the main visual motifs are the faces and bodies of contemporary Vietnam life, but also from archival footage. Were you concentrating on this motif, or was it just the outcome of the work?

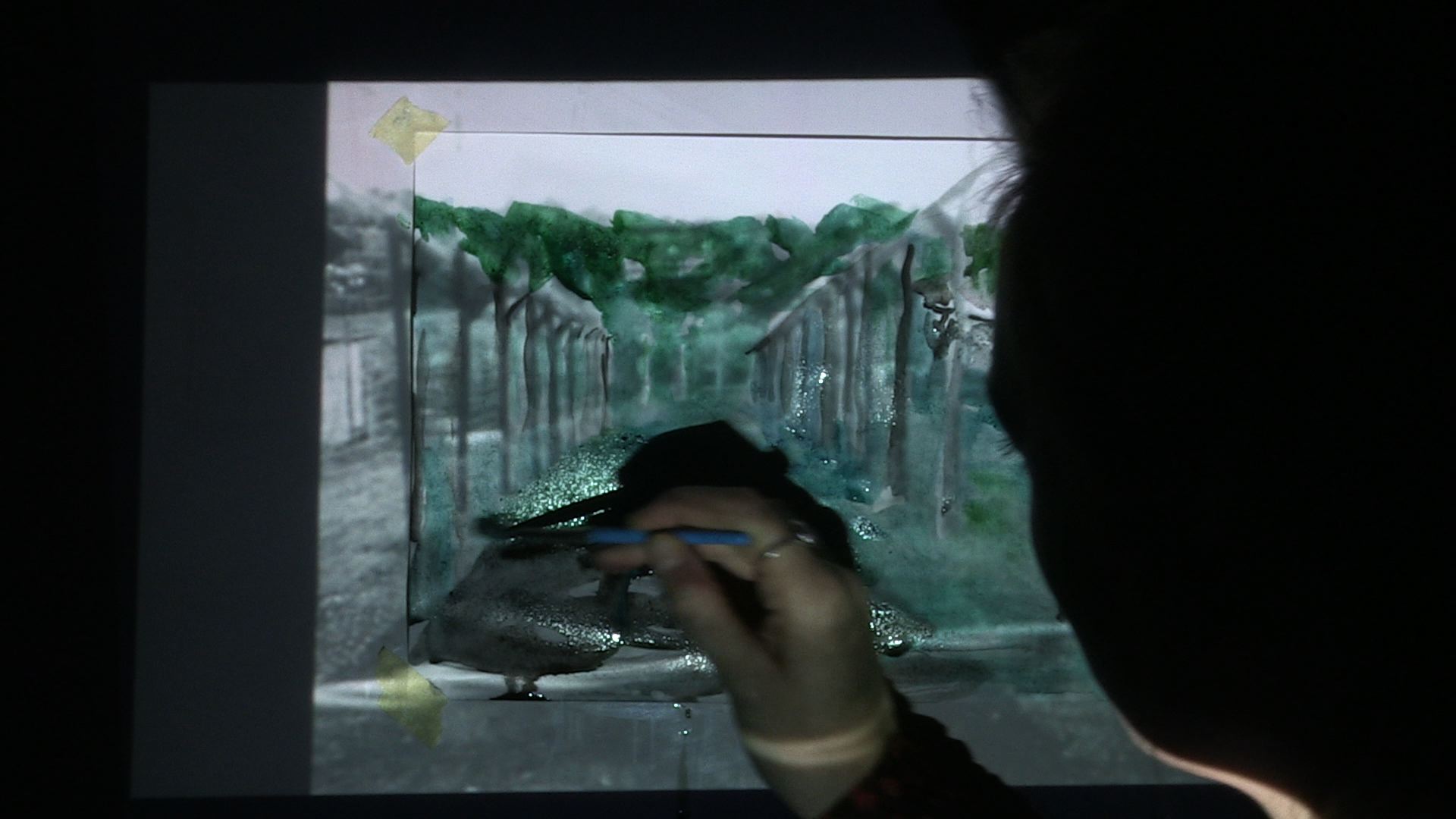

Mike: It came out of Josephine’s relation with the archival images. In the world of artist’s media, archives sometimes serve as props for a set of procedures, there is a kind of machine that operates on the footage. Instead, Josephine projected images, frame by frame, and then she touched them with her paintbrush. The pictures show life in a Vietnamese prison camp. How to return our bodies to this moment, to have a relationship with these pictures, not only to touch them, but to let them touch us? She lets the circuit run through her paintbrush as she fills in the grass, or adds colour to a face or a hand. This touch brings these pictures back to the surface of the skin, to the present. She rescues this moment by touching it again.

Andrea: The film’s collection of faces and bodies is motivated by haptic contact. The way Josephine greets and opens to the archival images by painting on them creates a second level.

Mike: Over and over again, the film offers a present-day image from Vietnam, followed by a corresponding gesture from Josephine. A little girl blows up a red balloon, she blows up a red balloon, a hand reaches for a plant, then her hand reaches for a plant. There’s a man who opens shutters, he’s opening his heart to this city, this moment. Then we see Josephine spread her arms wide, in the same way. Her gesture is an echo or rhyme of the images that precede her, as if they are narrating a script for her to follow, as if her body is listening to the bodies from that other place.

Andrea: Can you talk about your use of sound, which evokes at times a barely suppressed violence, the memories of war or shootings, or feelings of strength and shame.

Mike: In their Dziga Vertov period, Godard and Gorin said that the class struggle in cinema was also the struggle between sound and image. We still talk about going to see the movies. They hoped to counter the primacy of vision by making the soundtrack more important than the pictures.

When John Cage went into the anechoic chamber to find silence, he heard instead the sound of his own heartbeat and the blood running through his veins. He taught us that there is no silence. We’re always in the midst of a soundscape that changes our sense of who we are, our political possibilities, our relationship with our environment. It is a reminder that identity is relational, and that our sense of ecology is grounded in sound and listening.

I can’t understand why people are frightened of new ideas. I’m frightened of the old ones… If you develop an ear for sounds that are musical it is like developing an ego. You begin to refuse sounds that are not musical and that way cut yourself off from a good deal of experience… Everything we do is music. John Cage

I try to give every picture its own sound. I try to give every sound its own picture. Sounds also create pictures and associations.

The Vietnam War, or as it was more properly named in Vietnam, the American War, ended in 1975. But the traces and consequences of that war are multi-generational, there were so many deaths and chemical poisonings. The Americans were trying to destroy a culture, an identity, ways of life. Present day Viet celebrations embrace new loves in rebuilt cities, but remain underscored by what must have seemed like an endless war, not only against the Americans, but before them the French. Some of those hauntings are evoked in the sound, the fireworks for instance, could also be bombs.

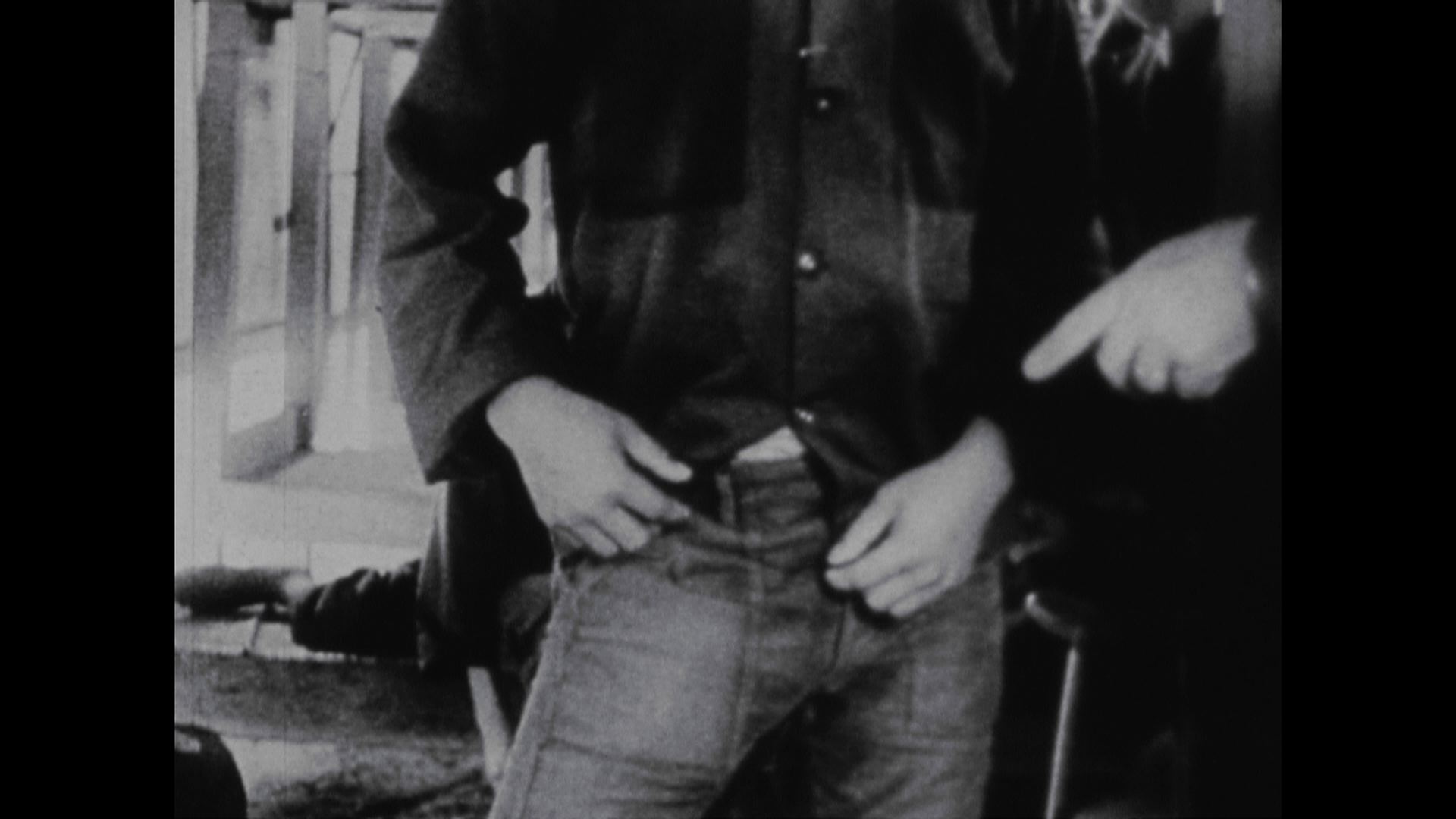

In the prison camp there is a harrowing scene showing two Vietnamese prisoners entombed in a black metal box. It is opened by a white man, presumably a UN observer, a visitor to the camp, who watches them emerge. It’s a shocking colonial moment. How to evoke the days and nights in that metal box, and how they are part of a system of punishment and identity?

Seeing happens at a distance, seeing is the way we create distance. But we’re always in the middle of sound. You can’t close your ears. There’s no escaping the relationship that’s developing in real time, in a soundscape. Often in conversation what is important is rhythm and flow, the tone of the voice. My friends are not the closest of all because they are information portals, instead we make space for each other, we exchange attentions, and these rhythms can be just as important as the content. Perhaps flow is content.

Andrea: Tone lends emphasis, it’s an oral highlighter, or else a way to signal ambivalence. It might be more memorable than the words it is supposed to support.

I was interested in one more motif in the film, the question of institutions. One set of intertitles read:

Father said: memory is a second chance.

Every life is the defense of a form.

A person who can give you an “I” can also take it away.

Schools are a machine for the production of children.

You were my school.

This passage recalled an earlier moment from your film We Make Couples (2016) where there was a clear parallel between the production of industrial goods and the production of relationships.

Andrea: If the bedroom, the kitchen, and the factory are sites of production, then alongside our sneakers and cars, we are also producing relationships, forms of resistance, even here.

Erin: Perhaps what I’m calling love is what you call resistance.

Both these films explore how relationships and identities are created out of institutional systems. In Touch Memory we see a prison camp whose purpose is to produce particular kinds of discipline, arranging bodies in space, along with their behaviours.

Mike: In one of the earliest moments of the film, someone reaches towards a plant in the Vietnamese countryside. This is followed by a scene in Geneva, where Josephine reaches for a plant in a hothouse, a controlled and structured environment. This creates a soft prelude for the camp memories that arrive later.

As you note: identity is a construction site. Capitalism links these two countries in asymmetrical relationships. Questions arise: how should we behave? How should we perform our genders? What does it mean “to work.” How might we reimagine education, which produces useful and productive citizens that can fit into a society governed by a ruling class? I hope the prison camp sequence raises some of these questions.

I’ve been researching the origins of capitalism to see how the nature of work changed. A different kind of work required a different kind of worker, all ages, no days off, total commitment. This was achieved using specific disciplinary techniques that have evolved over time. The surveillance state that we’re presently in is an extension of this project of disciplining bodies. It’s necessary that as workers we should be maximally visible and accessible. The home no longer draws a line between work and our “private life.” Homes are factories. And the new centre of our lives, the internet, is controlled by new ruling class mega-corporations, like the oil and railroad barons of the early twentieth century. Then as now, resistance flourishes. I see the Jihlava Fest as part of that resistance.