Message To Michael: Musings on Public Lighting by Jason McBride

Dear Mike, Last night, I watched Public Lighting for the first time. At least, I thought it was the first time. But I quickly realized that I’d seen it before – or at least parts of it – and that feeling was superseded by the realization that, as with many of your movies, Public Lighting’s familiarity stems from the fact that it’s made up, mostly, of other movies, images, sounds, words. If all books are in some way made of other books, the same goes, I’d argue, for movies. Few filmmakers explicitly acknowledge this like you do, or are able to so insightfully and elegiacally exploit this fact. The Dutch writer Esma Moukhtar intones at the beginning of Public Lighting, “Everything around me is writing.” I assume you wrote those words, but the sentiment echoes something that Moukhtar herself said about another film of yours, Imitations of Life: that we “never know where the words are actually coming from.” Your films are composed of an intricate interlace of language, a deft weaving of found language, quotation and original text. Words surround us, fall on us, illuminate and blind us – like light. If everything around me – you, us – is writing, then everything has been written into existence already, is just waiting to be read. It’s out there, public. Publication, to paraphrase Matthew Stadler, is the beckoning into being of a public. Public Lighting, I think, is a similar act of creation, creating a common space of conversation. Unlike with many other movies, your images always feel shared, not inflicted. They remind me, for lack of a more poetic phrase, that we’re all in this together, this constant cascade of image and language.

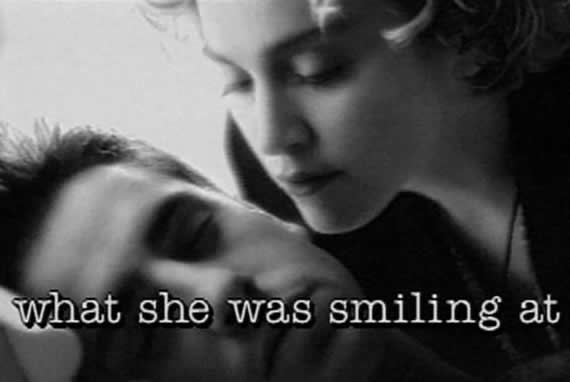

Moukhtar has heavy eyebrows, a hint of facial hair, and dark, thick ringlets that surround her face like a forbidding storm. She smokes compulsively, as if the cigarettes were made not of consuming fire but of sustaining light. She looks a bit like Frida Kahlo, or an old roommate of mine. I was living with this woman when I first googled something. Google was not then a verb, still hardly a proper name. What I first googled was you, Mike, your name. For real. I don’t think I’ve ever told you this. That search turned up a long interview with you from some obscure film magazine; I printed it and tucked into a file folder, alongside interviews with Chantal Akerman and John Cassavetes. We printed everything in those days. Words on the Internet were ephemeral, could too easily evaporate. They were only light. I wanted to make films then myself, and to my mind, forget Egoyan or Mettler or Cronenberg, you were the best model of what a real Toronto filmmaker could and should be. You made challenging, brilliant, elegant films that straddled art and cinema, sui genesis work that defied borders between fiction, essay and documentary. I met you once then, just briefly – you were showing something at the Ann Arbor Experimental Film Festival or were on the jury maybe – and a woman I was dating at the time introduced us. You smoked compulsively then. We all smoked. You were intimidating, with cheekbones as sharp as switchblades, a withering intelligence, that generous laugh.

I’m addressing to this you as if I know you, just as in Public Lighting you address Madonna as if you might know her. Or rather, as you have another surrogate, another voice that’s not your own, address Madonna. In that case, though, we all know Madonna, or at least know a part of Madonna, have an image of her. I imagine that far less people have an image of Mike Hoolboom, but that makes the image much more precious. I don’t know you well at all, and my knowledge of you is almost exclusively derived from your movies and writing. The letter in your film is from someone also named Jason. Not me. Someone who’s apparently had sex with Madonna. Not me. “It’s hard to watch you growing older,” Jason writes, truthfully, to Madonna. I think if he were writing his letter now, Jason would address it to Lady Gaga or the Beibs, two musical personalities who occupy the public imagination now in a way that Madonna did then. But maybe not, maybe he’d still write Madonna. She’s surprisingly endured, kept her finger pressed to the pop cultural pulse, shape-shifting, somewhat anyway, with the times. Her concerts in Toronto still sell out.

To stay in the mood to write this letter, I’m listening only to Madonna and Philip Glass; I’ve made a playlist that alternates the two. (Right now, I’m listening to Ray of Light, my favourite song of hers.) This brief missive can’t even begin to scratch the conceptual surface of your film. But I want it to at least embody its spirit, its associative logic, its personal, idiosyncratic digressions.

At the beginning of Public Lighting, Moukhtar says that the film presents six case studies, biographies that will demonstrate the six different types of personality (Madonna is a narcissist, Glass an obsessive, etc). But where does this taxonomy come from? As an organizing principle for a film, it’s helpful, but how do you implement such a tool in real life? What kind of personality are you, Mike? I expect most of us can’t realistically be reduced to a single type, that we shuttle between these six kinds of personalities as easily, thoughtlessly, as we switch tabs in an Internet browser.

As I lost interest in making movies – wrong temperament – I lost that folder with your interview. But our paths crossed again. The year I started working at Coach House Books, you published a second edition of Inside the Pleasure Dome with us and then later, brought Steve Reinke by so we could publish a volume of his writing. It was a great book, but I always kind of wanted it to be only an audio book – reading his words, separated from his videos, I missed the sound of Steve’s voice, that deadpan, nasally mellifluous sound that you use so expertly in the second section of Public Lighting. After I left Coach House, you published your first novel with them, ostensibly about Steve, and I reviewed it for the Globe and Mail, quoting Auden (the name you gave your protagonist): “A real book is not one that we read, but one that reads us.”

I started working on my own novel then too, with characters very loosely based on a pair of real artists, Emily Vey Duke and Cooper Battersby, good friends of yours whom Steve had also taught and mentored. I still haven’t finished it, but so far anyway, it’s a much different book than yours, grounded in a kind of naturalism that I don’t think interested you fictionally. But it asks some of the same questions that preoccupy Public Lighting: how do we tell the story of a life? How many stories make up a life? How, and why, do the fragments of biography become a narrative, and what happens when that narrative falters or fails? What poetry emerges then? What public is created? If I ever finish it, I look forward to you reading it. Not surprisingly, you make an appearance.

Love, Jason