Jury Notes: Awards at the Vila do Festival 2003

In 2003 I was kindly invited to sit on the festival jury for the Vila do Conde Festival in Portugal. We were a jury of five, and after we had made our choices I was asked to scribble out some reasons about why we had come to our conclusions. These were read aloud to a packed theatre, and after each award the artist (or someone on their behalf) would come to the stage and say a few words. Here is the jury text.

International Awards

Inside the machine of light that is the cinema there are some who insist on maintaining a hand-made quality, the gestures of a hand, the quiver of a line. For its shattered, breakneck depiction of the accidental catastrophe that is family life, and also its whimsy and good humour, an honourable mention in the animation category has been awarded to Canada’s Christopher Hinton for Flux.

The cinema began with a train, a train of thought which gathers up decades of image making in this year’s bravura work of extraordinary complexity and virtuosic technique, its manic, convulsive, shuddering chase scenes at once ode to and deconstruction of spectacles past. The detectives which haunt this film are also its audience, still longing for rapture, for cinema’s capacity to surprise and astonish, even as it looks back at itself, reflecting on a world it has remade into pictures which have shown us how to love and die. The great prize for animation goes to Austria’s Virgil Widrich’s Fast Film.

For its powerful depiction of the failed utopia of 50s science, for its elegant marriage of two genres: the melodrama and the science fiction film, its narration of a body under pressure, remade, remodeled according to the needs of a cruel machine which is at once the harbinger of a digital consciousness and cinema itself, an honourable mention in the experimental category has been awarded to German’s Christoph Girardet and Matthias Mueller for Manual.

This is the first year that a prize will be given for best experimental film, where an find a quality of risk, a marginalized form of seeing, and above all a first person cinema, born in the aperture of personality. There was one film which presided over this marriage of eye and I beyond the rest, a movie filled with an urgent waiting, with spaces no longer inhabitable, except by her camera, a space which has been remade into the nightmare of panopticon, the suburbs of America have never seemed quite so dark, so relentless, and so the great prize of experimental film goes to the United States’ Deborah Stratman’s In Order Not To Be Here.

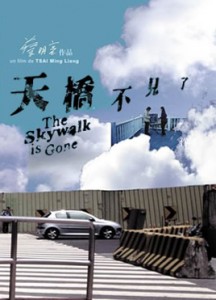

In narrative making of this kind there are no mistakes, no detail which has been overlooked, no moment of the frame which is not alive with a new kind of seeing. This movie, made by one of the most important filmmakers working today, luxuriates in the freedoms that the short film offers, in its density and compression, in short form, short hand for the more langorous expressions found in his feature films. The short films offers not the story of our lives but its dreamed double, in this instance, a love affair gone wrong, a portrait of a city, the economics of sexuality, all delivered in a wondrously understated fashon, precisely framed and choreographed, where the main events, the action, lie outside the frame, along with its audience, who are asked to venture into a world which refuses to be summarized in a word, a gesture, but asks us to live its questions, to look and look again. The great prize of fiction goes to Taiwan-French director Tsai Ming-Liang for La Passerelle Disaparue.

In the silver harvest of this year’s festival, there is one movie which shines a little brighter than the rest, which will leave the festival not just with the award for best documentary, but also the UIP prize for best European film. For its sublime evocation of a life which is vanishing in front f our eyes, its intimacy with ghosts, for its stately cinematography, for its willingness to breathe the same air as its subjects, live with them, open to them, delivering compassion in place of judgment and reminding us that if the cinema, as the Lumiéres declared, is an invention without a future, then it has also been, from the very beginning, an art of grieving and loss, of recording the traces of what was once, but not now, no more, ever. This film reminds us why cinema matters. The great prize for documentary as well as the European Film Academy Short Film 2003 at Vila do Conde goes to Belarus filmmaker Victor Asliuk’s My Zivem Na Krai, Living on the Edge.

Portugese Awards

The award for best actor in a Portugese film goes to no one. After a long deliberation the jury was unable to find a candidate for this award. Where are our men?

The award for best actress in a Portugese film goes to a woman whose sensitive portrayal of unexpected calamity, the long moments of grieving where going on is the only choice, and impossible, goes to Ferida’s Gracinda Nave.

For its beautifully concise depictions of a room, its gathering of details insisting that this small place is also the place of the body, trapped inside itself, for its economy of presentation, the award for Best Photography goes to the woman who shot and directed 5 Cm Para A Morte, Claudia Bandeira.

For its return to a subject too often shown with tired sentimental eyes, but which lives here again, in a self-assured and easy going exchange between the machines of seing and her subject, this is a filmmaker who is unafraid to wait, just wait with her camera in order to accompany the lives which are unfolding around her in spirals of trust and hope, the award for best young filmmaker goes to the maker of Marcado Do Bolhao, Renata Sancho.

And now at last to the prize you’ve really been waiting for. The award for best Portugese short film. You might have been noticing a trend, something shared by those receiving awards from Portugal this year, can you guess what that is? And if you’ve already noticed, I wonder if this trend could continue?

There was one film whose blend of fiction and documentary dared to take on the subject of a wounded masculinity, begun in a succession of decisive moments before unfolding their consequences, their reaction shot, in a series of dramatic interludes. The award for best Portugese short film goes to Ines Olivereira for O Nome.