- Images Festival 2000 (download as pdf)

Images Of Intermedia by Laura U. Marks

Afterimage, July, 2000

This year’s Images Festival of Independent Film and Video lived up to the challenge of moving across media, featuring installations, performances, a “smart-art” conference and numerous other live events in addition to its usual screening programs. Images dealt seriously with the question of how to run a film and video festival in the age of intermedia. Several performances were incorporated into the screenings: most notably A Stereoscopic Seance by Zoe Beloff with live sound by Gen Ken Montgomery, showed devotion to the quaint technologies of 78 rpm turntables, toy telegraphs, a pocket theremin and a Kodascope 16mm projector.

Getting festival participants off-site proved to be a greater challenge, but an installation program curated by Deirdre Logue rewarded curious viewers with, for example, the “Orifice” project of 12 site-specific works made for 3″ LCD monitors.

As the title suggests, the tiny videos, mounted in galleries and restaurants, gave those who found them a view into another world. There was also an installation by Austrian Leo Schatzl entitled, Head Jumper (1999), which shot a single frame every time athletic (or tall) festival goers managed to jump and hit a pink rubber ball with their heads, triggering a super8 camera. The resulting sequence of head shots will be compiled into a film. Most impressive among the installations and winner of the festival’s largest cash award was Willy Le Maitre’s and Eric Rosenzweig’s The Appearance Machine: An Autonomous System for Music and Language Composition (1999-2000), a video shot, edited, sound-mixed and fed live over the Internet. One by one viewers reveled in its mysterious images of humming animated trash from the comfort of a room-seized beanbag chair at the InterAccess gallery. Extending the intermedia theme, the half-day symposium “Honey Your Digitalia Are Showing” was a good opportunity to bring together artists at their smartest and academics at their most expansive, including a generous performance by British media theorist Sean Cubitt.

The festival was programmed by Toronto’s Mike Hoolboom, a prolific experimental filmmaker and lifeline to the fringe media community. Hoolboom has seen so much work as a juror on experimental festivals around the world that it is easy for an audience member to put oneself in his hands. Interestingly, perhaps one quarter of the works Hoolboom chose to screen were from 1997 or earlier. He seemed intent on reminding audiences of the wealth of experimental work of which any festival can only represent the tip of the iceberg. Hoolboom’s programming raised an interesting point in terms of the visibility of experimental media: there is such an overabundance of new media work being produced, that after a work gets into one or two minor festivals and is considered to have “been around,” it is never shown again unless the artist should happen to have a retrospective. In light of the rare opportunities to view any of this work at all, Hoolboom chose to show what he considered the best, rather than the newest, experimental films and videos.

The festival also included several retrospectives, with a spotlight on Barbara Sternberg, one of very few female experimental filmmakers in Canada coterminous with Michael Snow, et. al. The festival was also graced by several works by Artavazd Peleshian, who filters Armenian experience through Soviet montage-like editing. Sensuous and quirky Mexican videomaker Ximena Cueras, New York City animator Emily Breer and found-footage maestro Jay Rosenblatt also each had several works featured.

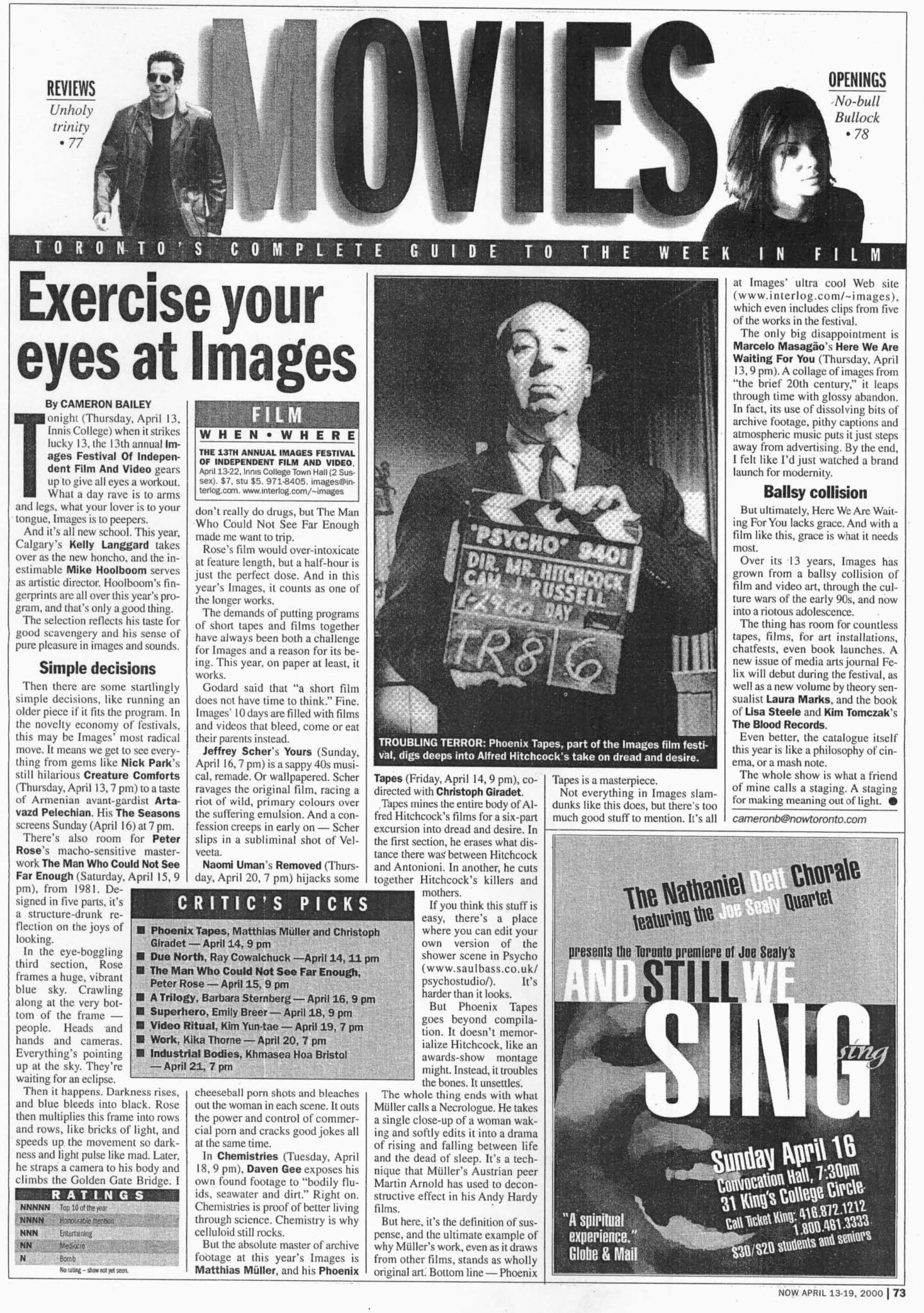

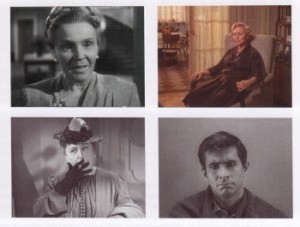

One highlight of the festival was Phoenix Tapes (1999) by Christoph Giradet and Matthias Mueller, a six-part deconstructive homage to Alfred Hitchcock commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford and named for the town from which Marian Crane departs in Psycho. Mueller says that while Hitchcock subsumed his virtuosic technique to the service of the story. just a little decontextualization reveals that he was arguably a modernist, even an experimentalist.

Burden of Proof was the perfect title for the metonymic responsibility of close-ups in Hitchcock films: all those gloved hands, hands nervously dropping keys, feet shoving dropped objects out of sight. Hitchcock himself acknowledged that oedipal themes are hidden in plain view in his films but it is quite wrenching to see them inexorably strung together in Why Don’t You Love Me? Phoenix Tapes concludes with a three-and-a-half-minute near-still image of Ingrid Bergman, apparently waking from sleep: digital frame twitching makes her eyelids langourously close, open, close again while a glistening tear rolls down her cheek and back up. Yet the attenuation of this moment in Hitchcock is not mocking but a fittingly embodied after-tremor to the series affective crescendo. Its title is Necrologue.

Filmmaker Helen Lee curated a program selected from a wealth of new independent productions in Korea. The most directly affective of these was The Refrigerator (1999) by Ahn Young-seok, a drama centered on a family whose life is modestly but irrevocably changed by the acquisition of a refrigerator in exchange for an absconded debt. In suavely captured realism, mom and children drench the father’s back with ice water after a hot day’s work and the little boy pees inadvertently on the family’s shoes after too many popsicles. A darker and more surreal view of Korean urban life was provided by Kang Man-jin’s Link (1999), in which a drunk man is robbed at knifepoint in the subway for nothing but his clothes and left shivering and naked to similarly assault the next passerby. Stunningly achieved in a single take, Link’s camerawork exhibits not only virtuosity but a kind of existential tact as the camera turns its curious gaze on overhead pipework while the most brutal moments of the assault take place. The darkly poetic Suicide Note (1999) by Lee Hyung-gon follows a strange encounter between a wandering boy and a plaid-skirted schoolgirl who records everything on her little digital camera, which she avers is her “suicide note” to a bolder friend who already took her life. Given that half of the population of Korea is under 30, as the program notes point out, we can speculate that the abrupt ascent to global economic power has taken its toll, in the form of urban anomie, on newly wealthy urban young folks such as those portrayed in these films.

Next to the works of global import were scads of wonderfully inventive “Small” works, including several Canadian super-8 delights such as Hair Pie (2000) by Lex Vaughn and Allyson Mitchell in which claymation cowpokes Pinky and Homo get in a nasty fight after Pinky wins the bake-off at the county fair and One Last Trick (1999), by a Calgary duo who call themselves Red Smarteez, which features fantastically detailed marionettes representing a pockmarked blond boy whose father, in time-warp moustachios and aviator shades, prostitutes him to famous movie directors so the son will get his big break (“You’re a real asshole, Dad,” says the squeaky puppet voice). A mini-retrospective of punk super-8 filmmaker Nadia Sistonen revealed an ongoing concern with perverse little performances for the camera, one featuring lipsticks swiveling so suggestively that I did not know where to look.

Images’ student film and video screenings promised exciting things for the future of independent media. The best film entries were those with the lowest production values. Process (1999) by Madi Piller, for example, took advantage of a ruined roll of film to make an impromptu animation about loss, peppered with hand-drawn expletives. But it was the video program that showcased pioneering experiments since the advent of digital editing. In Dorion Berg’s ASCII Alphabet (1999), each of a series of found pictures is mapped to a sound: a sheep = bleat, a flower = sigh, etc. The onomatopoeic tune that resulted was hilarious, but the implication that in a digital universe all correspondences are known in advance was rather disturbing. Other student videos revealed the new urgency of performance in a time of hyper-mediation: in Michelle Kasprzak’s Audition #37 (2000), the artist challenges convention by brushing her teeth at bus stops, ATMs and other public places, while Jonathan Plante’s Image no. 1 returns to the live aesthetics of early 1970s video in a performance for fixed camera where another person’s feet vie for central placement, only to ultimately knock the actor down. These and other technology-driven videos, selected by a student jury, were an additional breath of impatient life in an already heady festival.

Work (1999), a stunning digital video by Toronto’s ever-lively grrrl filmmaker Kika Thorne, finds a nonlinear way to “tell” the story of a woman who gets fired from her crummy office job but still finds happiness. Each scene is shot from a slightly different angle and presented on adjacent screens, so that rather than following a story from a particular point of view, we experience a series of tableaux. Thorne uses the open form to multiply the affect of each moment rather than extend it into narrative.

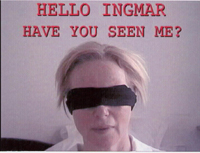

The “Plunder” program from Toronto’s Charles Street Video exploited the unauthorized speech of media appropriation. Gunilla Josephson, who acted in Ingmar Bergman’s 1963 Virgin Belief and Double Moral, used the editing suite like a shrink’s couch to explore the troubled relations female actors had with the Swedish master in Hello Ingmar? Have You Seen Me? (A Pilgrimage) (2000). Josephson redeems the performances of Bibi Anderson, Liv Ullman and other Bergman muses by adding accusatory voice-over and explanations of what really went on during the shoots. More controversially, on the home turf of universally beloved Atom Egoyan, was AK 47 (2000) by Robert Lee. Composed of 47 shots of Arsinee Khanjian, Egoyan’s wife and collaborator, lifted from his and others’ movies. Lee edits together scores of Khanjian’s mute, dignified close-ups, in a way that seems to simultaneously interrogate and adore her. In the film’s conclusion, he has the nerve to suggest, “If moments from her films were cut together, her entire body of work would be one endless performance.”

These highlights were truly the tip of the iceberg of over a hundred international, independent works. I can only conclude by humbly asking readers to visit the Images Web site where the programmers’ rich descriptions provide at least some sense of what remains to be seen. Given the increasingly live and ephemeral nature of the media arts, with the rise of performance and installation works, the best thing viewers can do is attend festivals and capture the moment for themselves.