- The Family (pdf)

Originally presented at the Image Festival, Toronto, spring 2006

The Family: They Fuck You Up

Two part program for the Images Festival, 2006. Screenings held at Jackman Hall, Art Gallery of Ontario. When it came time to roll the work out, I had come down with shingles, and hadn’t been away from the apartment for weeks, except to pick up some Percocet, a heavenly over-the-counter opiate which made getting out of bed possible. I cabbed to both screenings, did the intros and went immediately home, but not before being well met by almost-friends who invariably exclaimed, “Hey, I haven’t seen you around lately. You look great!” I smiled and tried to avoid any physical contact because my chest and back were filled with running puss sores. You just can’t tell by looking sometimes.

Program One: Life Swarms with Innocent Monsters

H is for House by Peter Greenaway 7 minutes 1976

In the form of the letter ‘X’ by Mike Cartmell 5 minutes 1985

Alpsee by Matthias Mueller 15 minutes 1994

In No Sense by Claudia Schillinger 11 minutes 1992

Sink of Swim by Su Friedrich 48 minutes 1990

Program Two: Love Objects

France/tour/detour/deux/enfants program 1: Obscure/Chimie by Jean Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville 26 minutes 1978

Sorry Suicide Girl by Kika Thorne 3 minutes 1992

Asparagus by Suzan Pitt 15 minutes 1979

The Right Side of My Brain by Richard Kern 26 minutes 1984

Mama and Papa: an Otto Muehl Happening by Kurt Kren 4 minutes 1964

Pretending We Are Indians by Katherine Asals 3 minutes 1988

Home Stories by Matthias Mueller 6 minutes 1990

This two part program shows the family at the end of its tether. Here, independent artists draw on the materials of their own lives and refashion codes of intimacy to examine the bewildering mix of chromosomes we call family. Assembled here are some of the very best film and video makers working today, whose images continue to illuminate situations rather than stars.

Program One: Life Swarms with Innocent Monsters

H is for House by Peter Greenaway 7 minutes 1976

In the form of the letter ‘X’ by Mike Cartmell 5 minutes 1985

Alpsee by Matthias Mueller 15 minutes 1994

In No Sense by Claudia Schillinger 11 minutes 1992

Sink or Swim by Su Friedrich 48 minutes 1990

H is for House by Peter Greenaway 7 minutes 1976

In this, one of Peter Greenaway’s early short films made before The Falls, his mature style is already very much in evidence. Though obsessed as usual with order, systems and the means of classification – H is for House – unlike his later set pieces, is about home. This is a structuralist’s home movie, its alphabetic accounting not yet marking our inexorable progression towards bodily decay and ruin, as Greenaway’s camera creates a pastoral frolic suffused with the light of the English countryside.

In the form of the letter ‘X’ by Mike Cartmell 5 minutes 1985

In 1985 Cartmell began Narratives of Egypt , a four-part series that deals with the father ( Prologue: Infinite Obscure ), the son ( In the form of the letter ‘X’ ), the lover ( Cartouche ) and the mother ( Farrago ). Throughout, the act of naming doubles as an organizing principle and thematic undertow. The second film in the series, In the form of the letter ‘X,’ is a signature – a filmic equivalent of Cartmell’s name (which is reduced by exhaustive transcription to a simple X). X is the mark of those who cannot write, or who do not know their own names. It is also a crossroads, a meeting place. Photographed over time against a backdrop of the Canadian Shield, X shows Cartmell’s son running in slow motion towards the camera, and, in the film’s second half, away from it. The music is taken from a Zombies tune whose opening riff is looped and repeated, held in suspension until the the song breaks into its opening lines over the final image: “What’s your name? Who’s your daddy?” Intertitles lifted from Melville’s Pierre relate the tale of a graveyard search, a hunt through pyramids, only to find that the caskets are empty. The search for ancestors is foiled. There will be no return.

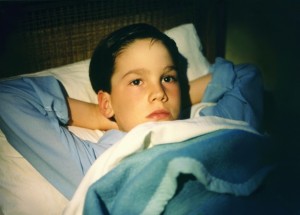

Alpsee by Matthias Mueller 15 minutes 1994

Alpsee revists Mueller’s earlier Final Cut , rendered now inan elegant, high-gloss style and shimmering colour palette borrowed from the 50s. Like Final Cut , Alpsee revolves around the relationship between mother and son, but while the former devolves into a granular first-person universe, the latter uses dramatic rhetoric to narrate the rhythmic inerplay between a young boy’s longing and his mother. Photographed with restless inventiveness and an exquisite eye for interiors, Alpsee stages a boy’s coming of age, the painful shift from infant dependency to mature individuation. The gorgeous chromatic scheme and high-tech lighting mark a significant departure from Mueller’s narrow-gauge efforts of the 80s, yet he maintains his characteristic syncopation, his miniaturist’s eye for detail and his resolute focus on the painful tensions pulling at mother and child. He reinvests the everyday with a trauma that is both historical and familial. That his empathy with his subject is so perfectly borne into the apparatus makes him one of the fringe’s most powerful and most perfect artists.

In No Sense by Claudia Schillinger 11 minutes 1992

For those who thrilled to Schillinger’s previous short, Between , this will come as a surprise. While Between featured a grainy, hand-processed take on gender bending, dildos and subversive desire, seen always in a night time dreamscape, In No Sense is cast in the vivid light of day. Photographed in a high gloss colour, it narrates, with haunting ambiguity, the relationship of a father and his young daughter. While the film luxuriates ina pre-adolescent sexuality. It manages to negotiate the treacherous divide between love and lust. Exquisitely shot, with an uncanny sense of framing, In No Sense ‘s immaculate direction offers its audience a darkly-drawn portrait of home.

Sink of Swim by Su Friedrich 48 minutes 1990

This award-winning short has been justly celebrated the world over as a triumph of first-person cinema – a diary whose perfectly measured recollections soar with a grace, intimacy and reassurance rare in any endeavour. Structured as a succession of 26 stories with epilogue, this alphabetic primer draws on myth, fairytale and personal reminiscence to draft a painful history of growing older. Impelled by Friedrich’s signature (underlit) grunge photography, Sink or Swim ‘s gorgeously rendered circuses, muscle-women, brides, Japanese pornography and bathing rituals crowd the screen, as successive voice-overs are recited by thirteen-year-old Jessica Lynn. Her voices takes us backwards through the alphabet, refashioning masculine dictates of history through the rich anecdotal detail and imagination of a woman who has managed to grow older without leaving the past behind, who is prepared to speak again as a child, though informed now by a lifetime of incident and mourning.

Program Two: Love Objects

France/tour/detour/deux/enfants program 1: Obscure/Chimie by Jean Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville 26 minutes 1978

Sorry Suicide Girl by Kika Thorne 3 minutes 1992

Asparagus by Suzan Pitt 15 minutes 1979

The Right Side of My Brain by Richard Kern 26 minutes 1984

Mama and Papa: an Otto Muehl Happening by Kurt Kren 4 minutes 1964

Pretending We Are Indians by Katherine Asals 3 minutes 1988

Home Stories by Matthias Mueller 6 minutes 1990

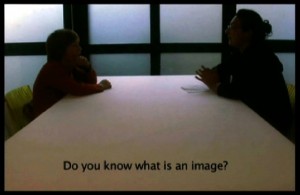

France/tour/detour/deux/enfants program 1: Obscure/Chimie by Jean Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville 26 minutes 1978

“Cinema has always looked at the world less than it has looked at itself. And when television came along, it quickly replaced the world and didn’t look at it anymore. When you watch television, you don’t see that television is also watching you.” (Godard) After his nouvelle vague features of the 60s, and the Dziga Vertov agit props of the next decade, in the late 1970s Godard hooked up with Anne-Marie Miéville to produce a series of radical television programs. Mieville had worked as set photographer on Tout Va Bien in 1972, before traveling with Godard to Palestine to co-direct Ici et Ailleurs . Together they moved to Grenoble and formed Sonimage, a small Swiss studio which would produce several features and some of the most remarkable television ever broadcast.

This is the first of a twelve-part series that imagined television as the new home for the family – the site where “family” could be staged and rehearsed. Godard/Miéville visit a single family here whose two young children, girl and boy, form the alternating focus of six pairs of programs. Tonight’s inaugural show focuses on Camille, the blonde innocent who proves an irresistible foil to Godard’s hilarious philosophical discourse on being, doubles and the medium of the family itself. Boldly provocative and characterized by an incisive wit and withering social critique, Paris/tour… stands as a testament to the potential of television as it might have been, if it had been spared the task of issuing a pacifying banality.

Sorry Suicide Girl by Kika Thorne 3 minutes 1992

A low tech homage to death and desire, Girl ‘s symbols of mourning include a photograph of the artist’s sister as a teen, months before her suicide. Thorne’s hand hovers over the image, looking to reach past her death and re-animate once more her sister’s memory. Thorne’s voice speaks throughout, recorded on a failing cassette machine that causes it to run faster and higher in pitch, her voice now more closely resembling the child she once was. Her addresses is aimed at her present lover, whom she slowly fists. As her fingers enter the other woman’s body she remembers her sister, and her lover’s cunt becomes a Madeleine — source and repository for remembrance.

Asparagus by Suzan Pitt 15 minutes 1979

Rendered in the traditional cel animation style more usually associated with Disney, Pitt’s Asparagus is a deliriously coloured and carefully wraught staging of artistic longings, in a distinctly feminist vein. Surreal in application and chromatically delectable, it depicts a woman entering a forest of towering asparagus spears and stroking them slowly. Later, she shits them out, their careening toilet-whir spelling out the film’s title. A hallucinogenic meditation on the making of art, Asparagus ‘s dark longings and immaculate realization make it one of the hallmarks of American independent animation.

The Right Side of My Brain by Richard Kern 26 minutes 1984

Richard Kern was part of New York’s Cinema of Transgression, popularized by chief dude Nick Zedd and fuelled by the post-porn patois of Lydia Lunch. Here Lunch writes, stars and adds music to a lurid, four-part saga of an isolated nymphomaniac determined to make it with the dirtiest sleazebags she can find. In a breathy rasp, Lunch delivers a non-stop rap about the body as pleasure palace and torture chamber. She gives a sterling performance as she relentlessly boils down every relation to sex and every sexual act to power. Photographed with rare economy in super-8, Right Side is a primer of the politically incorrect, determined to make its audience squirm.

Mama and Papa: an Otto Muehl Happening by Kurt Kren 4 minutes 1964

Two major figures of the Austrian avant-garde began their work in the 1950s: Peter Kubelka and Kurt Kren. But while Kubelka soon made his way to America and established himself firmly within the pantheon of its burgeoning underground cinema, little note was made of Kren, whose flickering, structuralist studies would receive scant attention until his American migration two decades later. Much of his work applies rigorous editing systems to a carefully arranged subject — whether photographs of dangerous offenders, trees in autumn or abstract paintings. But he also applied his furious montage technique to collaborations with a pair of notorious Viennese artists: Otto Muehl and Gunter Brus. These performance documents feature a flagrantly transgressive humanity that owes much to Artaud. Here, a howling naked chain of bodies is joined in rituals of blood and sperm, aiming always towards excess, annihilation and ecstacy.

Pretending We Are Indians by Katherine Asals 3 minutes 1988

Pretending is a fugue of past and present, as a family’s oral history is strained through a skeptical narrator. Deploying an unadorned voice-over, the filmmaker recalls the passing down of stories from previous generations – the myths and secrets that have influenced her own narratives. A succession of step-printed forest walks form the film’s spine, its super-8 original arrested here in a rapid procession of freezes. Between this succession of fall colours lie animated vignettes which support the speaker’s reminiscences. Beautifully rendered in paint-on-glass tableaux, their evanescence and rapid transformation lend vitality to this recall, as the musings of one generation are scrutinized by the next.

Home Stories by Matthias Mueller 6 minutes 1990

Comprised entirely of 1950s Hollywood extracts, Home Stories manages an elegant deconstruction of its originals while reconfiguring fragments into a haunting medley of domestic terrors. Discrete scenes of women (peering out windows, running past emptied halls, anxiously turning their heads) are blended ingeniously — with the painstaking craft that marks all Mueller’s practice — into a single, unified story. Stripped of their original narrative, these fragments remain charged with melodrama and suspense, as their deliberate blocking moves the protagonists toward the expression of a single, heightened emotion. The original narratives have dissolved into the architectures that close in upon them with a palpable sense of menace. With all of its grand Technicolour interiors scrubbed to a uniform shine, Mueller reconvenes the home as an architecture designed to contain female desire. His persistent use of frames within frames — doorways, windows, and headboards crowd the composition – lends a keen sense of visual enclosure.