- Archaeologies of Gender (pdf)

Archaeologies of Gender: recent Canadian experimental film

Presented on Australian Tour: Experimenta Festival (Melbourne); Brisbane Cinematheque; FTI, Perth; Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney.

The works in this program are among the best produced in Canada over the past decade. The multiplicity of forms and careful design of the eight films are testimony to the continuing richness and relevance of experimental film.

Archaeology of Memory by Gary Popovich (13 minutes 1993)

Begun with a series of scratches on emulsion, then rapidly mutating into a condensed history of representation, Archaeology relies heavily on home-movie memoirs. Lavishly coloured and featuring a symphonic montage of six image rolls printed together, the strategy to ‘begin at the beginning’ soon gives way to a phantasmagoria. Two lovers moving in a staccato embrace mark the centre of this centrifuge while beats roam a universe of pictures. Frenetic passes of super-8 pixillation unwrap pictures of home – Niagara Falls to this filmmaker – as a grotesque public sphere stuffed with wax museums and bad hotels. Beyond these illuminated receptacles are images of a more personal order, where Popovich joins the home movies of his father with his own.

In the form of the letter ‘X’ by Mike Cartmell (5 minutes, 1985)

As an orphan, Mike Cartmell, ignorant of his origins, adopts this X as his signature. The letter ‘X’ is derived from the Greek ‘chi’ (hence Cartmell’s production company: Chiasmus Productions), a rhetorical term denoting phrases which cross in the mouth (the bitterness of defeat and the defeat of bitterness). In the form of the letter ‘X’ is structured like a chiasmus –the film’s second half repeats the first half in reverse. It features two sets of texts, one a chiasmatic rewriting of the first. And two sets of pictures, one right side up, the other upside down. Photographed over years against the Canadian Shield it shows Cartmell’s son running in slow motion towards the camera. He runs toward the source of the image and of himself, attempting a return to origins the filmmaker insists is impossible.

Sweetblood by Steve Sanguedolce (13 minutes 1993)

‘Sanguedolce’ in English means ‘sweet blood.’ This resodding of old world heritages marks the passage from father to son in a diary film of immigrants. Driven by a montage of fragmented voice-overs, Sweetblood ‘s pictures are drawn from a family’s history of self-representation which are endlessly reshuffled before the filmmaker’s restless probing lens. Mounting a series of snapshots on foam core boards, then photographing them in single-frame abandon, Sanguedolce presents a synoptic personal history. Superimposed over his photographic frenzy are dream texts presented one line at a time, culled from the maker’s dream diaries.

New Shoes: An Interview in Exactly Five Minutes by Ann Marie Fleming (5 minutes 1990)

Made in response to a call for contributions to an independent omnibus production entitled Five Feminist Minutes, Fleming’s documentary brief is a harrowing account of death, obsession and fantasy. It relates the story of a friend, Gaye Fowler. After breaking up with a lover, Fowler is subject to phone calls, sudden visits and threats. One day just before going to work he arrives at her front step waving a shotgun. She tries to run back inside the house but he shoots her in the back. Then he shoots himself. He is dead instantly while she is left behind to speak and to remember. While Fowler recounts her horrifying experience in a conventional documentary talking head, numerous cutaways show the filmmaker dressed in fairy princess garb. Coloured shards dance round the princess, lending her a whimsical fairytale air, innocent foil to the onscreen confessional.

Visions by Gariné Torossian (5 minutes 1992)

Torossian burst onto the Canadian experimental film scene with this hand-made student short, a screaming dervish of wounded sensibilities and riot girl attitudes. Lacking a 16mm camera, Torossian shot a couple of rolls of super-8 before chancing upon a discarded bag of 16mm clear emulsion and magnetic stock. Using this clear emulsion as a base she began a painstaking montage of her original footage, laying film on film in a kinetic montage of fleeting fragments. The images offer glimpses of women’s bodies, a dancer at work, a woman naked in paroxysms of self-induced pleasure. Breaking the flow of these multiplying vantages are a series of hand-written texts scratched directly onto black leader. Vision‘s wounded emulsions are set to a howling extract from Canadian new music composer R. Murray Schafer’s Equus, a choral swell that lends voice to its outraged inhabitants, howling back from a history of framing and enclosure.

As Seen on TV by David Rimmer (15 minutes 1986)

As Seen on TV may been seen as the avant garde’s response to television. It is a frank exploration of the effects of televised spectacle, using a variety of stock images to conjure delirium and illness. The film opens with TV’s ‘Toni Twins,’ blonde smilers advertising hair permanents who emerge slowly from a door, figured here as the portal of media spectacle. This couple opens and closes the film, moving back through a door at the film’s end, providing a frame of greeting and departure. A series of tableau lie between the doors of perception, each transformed electronically. Between these moments of excess, and separated from them by a foreboding audio signature, lies a naked man caught in the grip of epileptic seizure, his pained gestures of recoil simulating masturbation in the enclosure of his solitude.

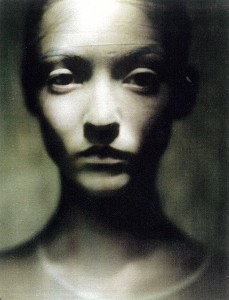

Whatever by Kika Thorne (20 minutes 1993)

Whatever takes up the thorny issues of race and identity in an elegant weave of experimental portrait, racial exposition, diary work and ‘coming out’ film. An inventory of personal experience is framed within racial questions and its host of invisible ideologies. Whatever turns around the talking head tales of Courtnay McFarlane, a young black gay male, who speaks of his lost patois, the importance of a black lover and the invisibility of blacks in gay porn. Animated, funny and reflective, McFarlane’s insistence on the political motivations behind private gestures, on a race-based understanding of his own desire, informs the swarm of white woman images which surround him. Imbued with a rapid and episodic montage, Whatever moves between McFarlane’s recollections with a deft and restless camera work, lensing a portrait gallery of girls at play. Interleaved with McFarlane’s racial expositions it is impossible not to see these friends-at-play as ‘white,’ engaged in the reproduction of whiteness.

The Evil Surprise by Francois Morin (15 minutes 1993)

“Technology is the knack of arranging the world so w don’t have to experience it.” Morin labours beneath this dictum to produce a hallucinatory optical printer film comprised of science segments, outtakes of 1950s films and frankly psychedelic releases, all joined in a riotous howl of overlays, wit and imagination. A blistering deconstruction of the utopian scientific vision of the 1950s, The Evil Surprise deconstructs from within, assuming a technocratic pallor in its traveling matte montages, each image the ground for the next as hallucination takes the place of rationalism, both figured here as the double-headed spirit that resides within the machine.