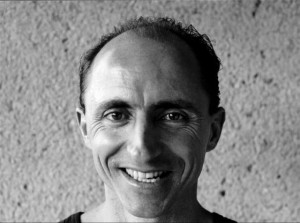

Frank Cole Retrospective

International Film Festival Rotterdam, 2010

(Variations on this program were presented at the National Library and Archives (Ottawa), Cinematheque Ontario (Toronto), Jihlava International Documentary Film Festival (Czech Republic), Northern Lights: New Canadian Cinema (Wroclaw, Poland)

Program 1

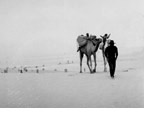

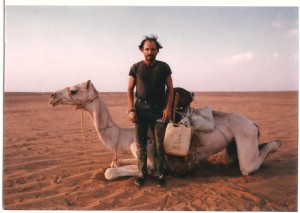

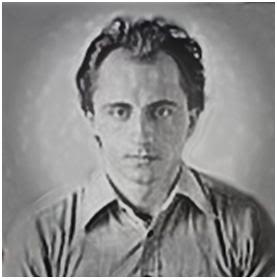

Legendary Canadian filmmaker Frank Cole entered the Guinness Book of World Records as the first man to cross the Sahara on foot. Meticulous, fearless, obsessive, and the maker of at least two bonafide masterpieces, there has never been anything in the cinema like Frank Cole. His murder in Mali left us with a legacy of two features, a pair of award-winning short films and a mystery that may never be solved.

A Documentary

8 minutes, black and white, 16mm, 1979

When Francois Truffault remarked that every director is condemned to remake their first film again and again, he might have been naming the project of Frank Cole. In Frank’s first short film, made at Algonquin College, he brings a terrifying mixture of intimacy and distance to bear on his aging grandparents. The camera is both stunned observer and an instrument of relentless pressure, urging its subject to go on, to show what cannot be seen.

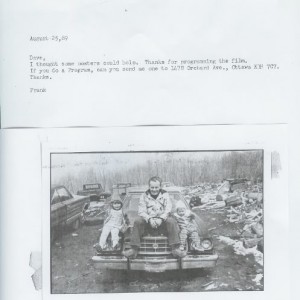

The Mountenays

22 minutes, black and white, 16mm, 1981

Frank’s second movie is a short black-and-white marvel of direct cinema. He visits the Mountenays family who live in a stretch of abandoned forest, next to an auto junkyard in the Ottawa Valley. The brothers appear first in a nearly endless succession, and even though it is winter they are busy out of doors for most of the day, hurtling past the lens on skis or cars or sleighs, laughing and falling over and having a good-old-boy time. No one is getting dressed for work or school or bending over seedlings or getting framed up into architectures reserved for growing up or getting old. They look feral, as wild as the animals that are roosting around coops that don’t seem much different than the big old house they all live inside. There is nothing frozen or stillborn or lost, no summary glance. Perhaps in the end there is nothing to add up, only another glimpse into a home life, parts of the long home movie that Frank was busy making whenever he turned on the camera.

The Man Who Crossed the Sahara by Korbett Matthews

53 minutes 2008

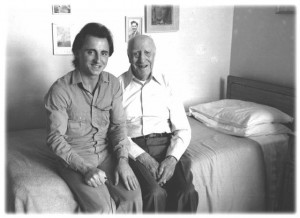

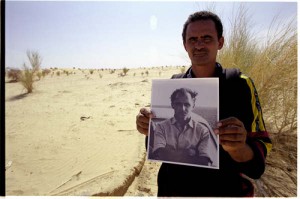

“The film opens with Cole’s grandmother dying from cancer, which he filmed, and probes the possible psychological reasons for his obsession with mortality in his work. With measured steps, it moves to the 11-month solo journey that made him the first North American to cross the 73,000 km long Sahara, which resulted in the award-winning film, Life Without Death. And, inevitably, it ends with his second attempt to cross the desert alone, which led to his death. Cole was robbed and murdered by bandits outside of Timbuktu, Mali, in October 2000. It was sunset. The killers have never been found. As if to challenge mortality one last time, Cole’s body was cryogenically frozen, and awaits the time when science may revive it. The Saskatchewan native grew up in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Czechoslovakia, Switzerland and South Africa, but called himself “a child of the desert.” Woven with interviews of Cole’s parents, best friend, colleagues and investigators, the film is deliberate, sobering and thoroughly compelling.” (Melissa Hank)

Program 2

A Life

75 minutes, colour, 16mm, 1986

Vito Acconci, Joan Jonas, Chris Burden… Frank Cole? Yes, with this movie Frank comes out as a performance artist extraordinaire. His body, like theirs, is a machine for producing pictures. A Life is Cole’s nearly wordless performance for the camera, with Cole back-and-forthing between a horizon-less Sahara and a room that contains only a desk and a bed. Figure and ground mash-up in a duet that sends his grandfather’s ashes scattered across a continent to create a newly emptied world. The long road of grieving brings him a burning car, a new tattoo and a long snake duet.

“Cole’s hermetic yet dazzlingly designed movie… is kin, in both its fetishism (blood, sado-masochism, body-building) and its feelings (they are repressed into a triumph of the will), to the “sun and steel” universe revived by Japanese novelist Yukio Mishima.” Jay Scott, Globe and Mail

The tribute to filmmaker Frank Cole will also serve as the launch for the new book Life Without Death: The Cinema of Frank Cole, edited by Mike Hoolboom and Tom McSorley. This 200-page volume includes contributions by John Greyson, Deirdre Logue, Steve Reinke, Geoff Pevere, Laurie Monsebraaten, Greg Klymkiw, Julie Murray and Yann Beauvais. A DVD of Korbett Matthews’ award-winning The Man Who Crossed the Sahara is included, along with a suite of colour photographs.

“Some called him brave, some called him mad, some knew him better. Above all, he was a filmmaker. This book has captured an elusive cinema chimera, a fata Frank morgana, a mirage of miraculous mirrors, a shimmering oasis, an optical delusion – as only a good book can.” Peter Wintonick, international editor POV Magazine

“Frank’s films display aspects of Canadianness that are (typically) pathological in their extremity, especially when it comes to sex, masculinity and the sheer impulse to get as far from human concern as is geographically possible.” Geoff Pevere

Life Without Death by Chris Robinson

(xtra, October 1, 2009)

I first encountered Ottawa filmmaker Frank Cole during a screening of his film A Life around 1991. He handed me a pamphlet that was from an organization that was anti-death. I remember laughing loudly. It was a good Monty Pythonesque gag. Cole, though, wasn’t laughing. He was dead serious.

As I later learned, death was Cole’s shadow, stalking every aspect of his life and films. His tragic death (he was murdered while crossing the Sahara Desert alone) came as no surprise to people who knew him. He had become obsessed with mortality, with living on the edge of life.

In memory of Cole’s uniqueness as a person and filmmaker, the Canadian Film Institute is launching a book about Cole’s life, alongside a retrospective of his brief but memorable films, featuring contributions by an assortment of friends, family, critics and Cole himself. The book, co-edited by Tom McSorley and Mike Hoolboom, also contains a DVD of The Man Who Crossed the Sahara, a documentary on Cole by onetime Ottawa filmmaker Korbett Matthews.

Xpress: Cole made just four films, yet so many people seem drawn to his work. What is so special and unique about Cole’s films?

Tom McSorley: Their formal rigour and the artful blend of documentary, fiction and diaristic modes of filmmaking. They have a strange combination of the deeply personal and aesthetically detached, forces of chaos and order barely contained in his remarkable frames.

XP: For people who might be seeing his films for the first time

during the CFI retrospective, what should they expect?

McSorley: Intensity. Frank’s work is confrontational. It is lean and muscular. It deals with the theme of mortality obsessively, but not without some humour. Frank’s work, intense as it is, is also filled with compassion for our human predicament.

XP: Where do you think Cole’s death obsession came from?

McSorley: That remains a mystery. The death of his beloved grandparents, who looked after him for a time when he was young, seemed to have some catalytic effect on his consciousness about death. This is not uncommon, I suppose – the fear of and obsession with our mortality and the frustration of knowing we cannot do anything about it. But I’m still stumped.

Obsessed with conquering death by Kirstin Endemann

The Ottawa Citizen, September 27, 2009

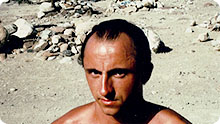

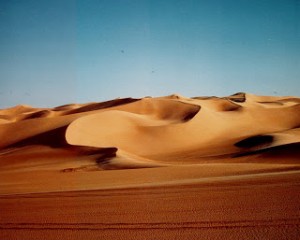

“I thought: a person would only come out here to die. I live best here. I understand it here, it’s like my room. It’s more home than home itself. It’s fearful however. The desert can make you want to die. That’s my only fear left.” Frank Cole, Sahara journal

Ottawa filmmaker Frank Cole did not win his battle against death. He did not wrest control from death by committing suicide at 30, as he had planned to do before finding there were other, life-extending options open to him, such as cryogenic preservation.

Death, he came to believe, was not a foregone conclusion to living.

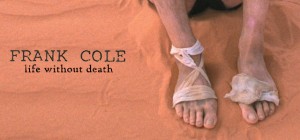

Yet he died in 2000 at the age of 46. His body was found tied to a shrub near Bel, Mali, where he probably was killed by bandits he’d been warned about before trying his second Saharan crossing. His first, from Mauritania to the Red Sea in 1989, won Cole a place in the Guinness Book of World Records as the first North American to cross the Sahara by camel, travelling most of the 7,000 kilometres alone, where he filmed his feature-length documentary Life Without Death.

Cole was as taken with the desert as with his self-described obsession with death and physical immortality; the two were inexorably linked in his mind and featured prominently in his four films (the others are A Documentary, The Mountenays, and A Life).

His films have been described as “difficult,” “masterpieces,” works of “uncompromising risk taking” and destined for greatness in the Canadian canon. The son of a diplomat with a penchant for sleeping on beaches while surfing the world, Cole himself was viewed as enigmatic, charming and controlling. Death, as the ultimate immovable force, became his locus and greatest fear, the Sahara its embodiment and challenge, muse contributors to a new book titled Life without Death: The Cinema of Frank Cole, published by the Canadian Film Institute.

Edited by media writer Mike Hoolboom and Tom McSorley, director of the CFI, it is an assemblage of commentary on Cole’s mostly autobiographical works by film professionals, colleagues, friends, family, but it quickly reveals itself as more than just cinematic criticism. It is a fascinating peek at the man, his fixation on corporeal immortality and his, as one writer put it, “recoiling from the fear of death by hurtling himself towards it” through extreme physical tests.

It is compelling reading to anyone who has ever toyed with nihilism, or those who adore the notion of adventuring, Indiana Jones style, into forbidding places.

Besides the frank analysis of his work, included in the book are excerpts from Cole’s Saharan journals, which, while touching on his fraught reasons for being there, are full of practicalities: how much water to carry, how to deal with an exhausted camel, avoid bandits and suffer extreme loneliness, remove sand from cameras and deal with corrupt bureaucracy.

Some of his correspondence sent back to Ottawa, also included, is amusingly oblique (a postcard scribed only with the words “Dead Naked”) or heartrendingly so (“Just earlier I thought I might be executed. What I felt wasn’t fear. It was sadness.”), leaving more unanswered questions.

It is obvious from the book that many of his friends and colleagues are left, after his death and demanding life, to struggle with the ideas that drove Cole back again and again to throw himself against death in the Sahara: notions most of us leave behind as sophomoric, unfit for the “real” world.

He, his fixation and films – remain compelling and challenging. The book reveals him as an adventurous and exhausting man (one friend refers to being “all Franked out”), with extreme personal discipline, fearless yet emotionally raw in his battle against time.

The book is a documentary in itself but it also includes a DVD of Korbett Matthews’ The Man Who Crossed the Sahara which examines Cole’s films, life, death and finally cryogenic preservation after his body, badly decomposed, was shipped home.

—

The launch of the book

Life Without Death and a film retrospective, hosted by the Canadian Film Institute and Ottawa International Writer’s Festival, will be held on Oct. 3 at 6 p.m. at Library and Archives Canada, 395 Wellington St. Readings from the book will be done by Frank Cole’s father, brother and other contributors.

At 7:30 p.m. Korbett Matthews’s documentary The Man Who Crossed the Sahara will be screened, followed by Cole’s A life and two of his shorter documentaries. On Oct. 17, Life Without Death, his documentary of crossing the Sahara, will be shown. All events are free and open to the public.