This month heralds programs by Mike Hoolboom from Toronto, and Solomon Nagler from Halifax. Friday, September 17, Mike Hoolboom will present Fear of Flying: Beauty and Power and on September 18, Solomon Nagler will present Blissful Discretion. Both of these screenings will take place at the Campbell Carriage Factory Museum, 19 Church Street, with a reception at 7:30 pm, an artist talk at 8pm, and the screening itself will start after sunset at 8:30pm. This is a free event.

O’er the Land by Deborah Stratman

51:40 minutes, 2009

Synopsis

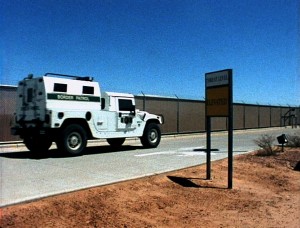

A meditation on the milieu of elevated threat addressing national identity, gun culture, wilderness, consumption, patriotism and the possibility of personal transcendence. Of particular interest are the ways Americans have come to understand freedom and the increasingly technological reiterations of manifest destiny. While channeling our national psyche, the film is interrupted by the story of Col. William Rankin who in 1959, was forced to eject from his F8U fighter jet at 48,000 feet without a pressure suit, only to get trapped for 45 minutes in the up and down drafts of a massive thunderstorm. Remarkably, he survived. Rankin’s story represents a non-material, metaphysical kind of freedom. He was vomited up by his own jet, that American icon of progress and strength, but violent purging does not necessarily lead to reassessment or redirection. This film is concerned with the sudden, simple, thorough ways that events can separate us from the system of things, and place us in a kind of limbo. Like when we fall. Or cross a border. Or get shot. Or saved. The film forces together culturally acceptable icons of heroic national tradition with the suggestion of unacceptable historical consequences, so that seemingly benign locations become zones of moral angst.

Artist Bio

Deborah Stratman is a Chicago-based artist and filmmaker interested in landscapes and systems. Her films, rather than telling stories, pose a series of problems – and through their at times ambiguous nature, allow for a complicated reading of the questions being asked. Many of her films point to the relationships between physical environments and the very human struggles for power, ownership, mastery and control that are played out on the land. Most recently, they have questioned elemental historical narratives about freedom, expansion, security, and the regulation of space. Stratman works in multiple mediums, including photography, sound, drawing and sculpture. She has exhibited internationally at venues including the Whitney Biennial, MoMA, the Pompidou, Hammer Museum and many international film festivals including Sundance, the Viennale, Ann Arbor and Rotterdam. She is the recipient of Fulbright and Guggenheim fellowships and she currently teaches at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Fear of Flying

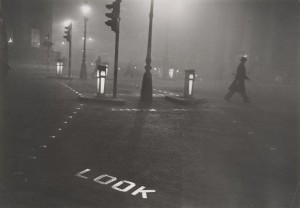

My Czech avatar Andrea, a friend to clouds wherever they might appear, urges me always to take a window seat whenever I’m off the ground, so that I might be able to examine once again the necessary atmospheric cover, so close I can nearly touch it, lying like wayward tufts of child’s candy. But while I thrill to look at clouds from both sides now, I never take the recommended seat, because when I look down I can see stretched before me a shrunken city of lights, a miniaturized movie set with dollhouses and toy cars and invisible strings tugging at it all. The airplane grants me an “overview.” I am riding, along with my fellow passengers, “above it all,” and perhaps it’s all those Vietnam newsreels I watched as a child, but I can’t help feeling that this view is some necessary preamble to destruction. It is not only the ability to kill at a distance, which the airplane offers as an extension of the gun, but those humans are so far away from the smilers that offer me snacks and entertainment devices, that it’s difficult to regard them as comrades. Those tiny coloured dots in the landscape are only design elements now, and no longer parents and children, ailing mothers and teenagers hoping to fall in love. After lift off ‘they’ have become faraway abstracts that can be stepped on, gassed, strafed, and bombed. Call it the royal view. The friendly skies.

Central Character

The main character in Deborah Stratman’s O’er the Land (52 minutes 2009) is never seen, though he speaks almost obsessively about his body. Yesterday, at Hartley’s fourth birthday party, I met a Frenchman who scratched himself continually as he spoke. It was as if his restless fingers needed to remind him: you live here, this is your body.

Stratman offers us Colonel William Rankin, a US airforce pilot, forced to eject from his fighter jet while running errands over America in 1959. He leaves his plane 48,000 feet in the air, and promptly gets caught in a massive thunderstorm for nearly an hour. He is frozen, burned, flattened and broken. No longer above it all, he is propelled into his very own contact narrative, just another part of the natural world. But unlike the singsong nature happiness strung up in rhyming verse by the Romantics, the natural world Rankin encounters is harsh, overwhelming and entirely indifferent. To risk stating the obvious: he doesn’t belong here. And what is most surprising, apart from his sheer survival, is the fact that this extreme threshold experience never budges the speaker, it doesn’t make any real impact on him at all. Perhaps it is because his rigorous military training allowed him to disengage from traditional panic buttons, but it’s strange to hear him speak of his encounter, and in such exquisite, storytelling detail, as if he was reading someone else’s newspaper account. Not for him the credo: biology is biography. Instead, he has turned his body into a fighter jet, and converted the natural world into a set of conditions which can be calculated and overcome. Even when he’s in the midst of his own death, he’s still working out the math, the subtle geometries of descent, the probabilities of system failure. He appears to himself as a tiny coloured dot on the landscape, far away from his own frozen, shattered husk of self. How else could nature be encountered by this faraway body, except as an ordeal to be endured, a set of distracting circumstances that might impede the functioning of this meat instrument?

Re-creation

Each year, thousands of men (and a few women) take part in costumed war re-enactments sponsored by groups with names like Panzer Grenadier Regiment (UK), Medieval Rose (Greece) or The Brigade of the American Revolution (US). Full regalia includes painstakingly replicated guns, swords, muskets, spears, tanks, maces, tomahawks, canons and more. Drills and rehearsals are run “in full kit,” members solicited, ranks assigned. It’s déjà mort all over again. Is it the lost pleasure of predictable outcomes they are looking for, a child’s delight in becoming someone else, or war by other means?

In O’er the Land, Stratman lenses a reenactment of The French and Indian Wars, an 18th century bloodfest that saw English troops vying for North American control. Although “successful” (ie. more French soldiers than English were killed, followed in short order by Native massacres (their punishment for choosing the wrong side), the bankrupt English treasury laid extra taxes on their colonies to make up the deficit, which led in part to the breakaway American revolution a decade later.

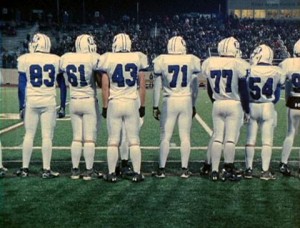

Stratman plants her camera in bucolic natural surroundings, and favours wide shots that lend equal weight to background and foreground. She shoots these weekend soldiers “in the back,” from behind almost-enemy lines. This not-quite-embedded reporter finds a reaction shot in the seated child scrums that gaze distractedly at their tarted up dads strolling across the green with muskets raised and ready. Here, colonial expansion returns as family entertainment, where the unsteady columns resemble nothing so much as halftime shows – part spectacle, part home movie boast – the clumsy mathematics of bodies ironically working to erase any trace of death or dying. But wait. Perhaps they are not performing an act of memory, or even grieving, but enacting a pantomime of past traumas. How did Marx put it? Everything in history appears twice, the first time as tragedy the second as farce. Enter the reenactment. The sanitized battlefield quotation. Or is it darker than that, dad? Perhaps the persistence of long ago traumas includes spectaculars of disassociation like these, featuring the compulsive need to act out, to recall physical sensations of generations past, as if nations, too, might be haunted by their unconscious, forced to repeat their trauma-struck fixations.

Sidelines

From the battleground Stratman delivers us to the football field, a sport that measures territory in gains and losses. The aim is ball control, possession, contained violence, maximum impact, and above all, as Stratman shows us – marooned once again on the sidelines, where the real action is – the rubbing together of male bodies. This is how we come together, as men, this is what groups of men create. Geography as a sign of power. The “land” is marked and gridded for easy reading, the billiard-table-smooth artificial turf laid over unnatural ground. The players appear as parodies of masculinity with their outsized shoulders and spiked shoes, ready to “pay the price” for every precious bit of real estate. But the drama of pulled tackles and perfect spirals is not the lure here, instead, the filmmaker serves up end zone cheerleaders and sidelined brass bands. The game itself is a distant afterthought, strictly backdrop material for the identity/behaviour vectors that are busy forming in its wake.

RV Park

There is no voice to guide us in the filmmaker’s darkness, no easy line of words to follow as we are asked to make the jump from one scene into the next. From the football field we are hotwired into an RV park at night, the gathered parking lot of home filled to bursting with one mobile promise after another. These car homes appear as specimens from a forgotten zoology manual, and I am filled with questions like: how does she manage to film these vehicles as if she’s never spent a day on earth? How does she impart a necessary distance so that we are able to see them not as the temporary stage for our own restless hopes, but as if we are looking forward in time from a moment when these fabulations were not yet conceived? We, the audience, the mute spectators, are asked to see through the eyes of the ground itself, the kilometers of worn road, call it landscape if you must. But it is animate here, a moving presence amongst these toy houses on wheels, with their miniaturized suburbias, their calculated innoculations against experiencing anything at all. The armour that still passes for the good life. Painless and numbly faraway.

Women

There are not a lot of women who wander out in front of the filmmaker’s maternal stare. Instead, this essay demonstrates a world bricked up by men, only they can’t seem to get the proportions right. Everything appears too large or too small. Everything is a tool or a machine or a game, in other words, extensions of the sandbox. And all the men appear in costumes barely graduated from Halloween. It’s kid town, it’s hide and go seek with nuclear weapons, it’s cops and robbers with border trackers and firemen. Stratman leans on wide shots filled with scape which make these boy-men appear as frontier clowns, lapsing for moments into accidental rapture as a group of amateur flame throwers, before returning to an aimless rage in the father-sun submachine gunning of a designated car target.

Perhaps saying frontier clowns is too much. There is still something friendly, almost accepting, in the way that the filmmaker looks at her charge, almost forgiven. As if they can’t help themselves from doing that, again and again. Somehow her looking has a mother’s touch, which lends a necessary ambiguity to this project. She dodges the polemical screed, the one-sided vanishing point of an argument, by insisting on not-knowing, on some suspension of judgment, which she offers her viewers as a gift.

And yet. Everywhere she looks I can see the drive towards abstraction. The scientific faith, the blindness that impels progress, and the deeply infantilizing succour of rationality. This is an America that has never grown up. That refuses to grow up. Experience, as Colonel Rankin makes clear in his post-self memoir, is no teacher, it only gets in the way of the Idea, the mission, the code; or whatever is being laid over the present to keep it from happening. Above all don’t make me feel. I’m OK, You’re OK. The kids are alright. Let’s keep the ball moving forward, a rolling stone gathers no nuclear dust, and that smoking gun doesn’t belong to me, it just walked over and put itself in my hand. It’s not my war and he’s not my president. It wasn’t me, officer.

Take, eat, this is my empire

Everywhere in O’er the Land, America’s cherished certainties have frozen into childhood idylls which might be charmed sideshows if they were not the symptoms of an imperial culture – grounded in genocide, raised on a messianic myopia, and determined to kill anyone who gets in the way of a global Lebensraum. It began with the Native population, who were nearly slaughtered down to the last woman and child, and then the home of the braves ran south, plundering the waning Spanish empire, land grabbing from their Mexican neighbour, setting up concentration camps in the Philippines and military dictators in Cuba, Guatemala, Iran, El Salvador, Chile, Nicaragua, Vietnam… All in a day’s work. How does all that killing look at home? Like a whole bunch of Mcdad’s at the Machine Gun Festival, perhaps, sharing with their first borns the joys of a simulated kill. Or the Viet Cong re-enactors who wait for the filmmaker to give them direction. What part do I play? What do I do next? There are enough corporate media outlets offering ice cream castles in the air to keep these imperial eyes wide shut, ignorant of America’s secret torture prisons, the White House hit squads, the extraordinary renditions, the Christian mercenaries in the Holy Land, the endless sabotage of the Palestinians, the drone massacres in Yemen and Pakistan. Neo-liberal capitalism turns out to be war by another name, and there are few enough in the self-named “avant-garde” of American movies who have been willing to say anything about it at all. No doubt, they have more important things to do.