Good Candy: an interview with Jason Anderson (December 2008)

Jason: Why do you think you’ve been involved with so many writing projects lately? Were you working on films in tandem or did this spate of literary activity serve as a break from the editing room?

Mike: Writing is the secret that I have been busy keeping from myself. I was one of those kids who saved their Halloween candy. Only the most unwanted discard was permitted, the rest was cached for some future perfect moment. More than once, an entire year passed with the basket still brimming full. Writing has always felt like the good candy, the rockets and twizzlers and chocolate everythings. Movies are apples.

Jason: Was the development of the novel very different than the creative process that goes into making a film? What sorts of things did the novel allow you to do or explore that you wouldn’t have been able to do in a film?

Mike: The Steve Machine had to be written while I was pretending to do other things. It was scribbled on napkins and coasters and the margins of foreign newspapers. The point was never to be caught working at it, because then I would freeze and all the words that cozied up at night would simply rush from the room. Movies, on the other hand, are the necessary seal which keeps out the unexpected, the unbearable, the new. They are only partially successful at this, So their restless vigil must be renewed as often as possible. I’m always working on a movie it seems, while I’m never writing a book, especially when it’s being written.

While my movies are filled with stories, it’s hard to imagine a plot-driven confection, at least in part because of the required means. In the novel, new cities appear with a few jabs at the keyboard. And then disappear again. And while there are reps and houses and awards, a book is not judged wanting simply because it didn’t cost a lot of money to produce. Spending a million dollars wouldn’t have made my book any better, though it would have paid for a lot of back rubs.

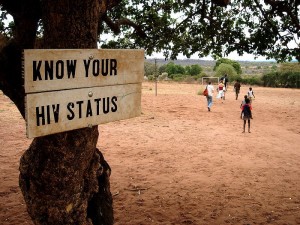

Jason: Living with HIV has obviously been a primary concern in many of your film works, yet The Steve Machine offers a very different take on the subject. Did the process of writing a novel encourage another kind of approach? (The “plague journal” mode mentioned in Greyson’s blurb comes to mind, though the novel’s form is too elastic for The Steve Machine to be considered any form of diary.)

Mike: The most true-to-life parts of the novel are fiction, while those few moments which are lifted from conversational gambits with friends or indiscreet encounters seem already covered in the tall tale glow of speculation. Somehow, the novel turns documentary into fiction.

The AIDS pandemic is a long distance runner. When I made Letters From Home, a dozen years back, the voice-over said, “While you’ve been watching this film, five people have died of AIDS.” Today the number would be much higher. Some of the movies have a messaging urgency as a result, which is good for the message, and not so good for the movies. My novel, on the other hand, is a comedy and a love story, and was written in meringue. Its short chapters float past without any effort at all, and while I had hoped to endow the book with a circuit which would permit pages to turn by themselves, this seemed too much like a James Bond ploy.

One of the book’s new joys is that, unlike a movie, it’s rarely ingested in a single setting. Instead, it continually vanishes and re-appears in new settings; already it has been washed up in faraway vacation spots and local laundromats. I imagined it like a visiting friend whispering secrets. And while I am prone to inventing blind spots in my movies, I was saved from the worst of these by my genius Coach House editor, Alana Wilcox. She was not only the first reader, but she lent the new book new eyes which dissolved everything which did not quicken the pulse.

Jason: What made Steve Reinke and his Hundred Videos project so ripe for mythologizing?

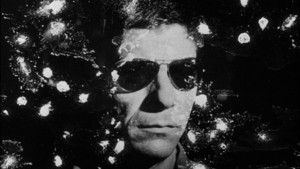

Mike: Steve’s first video was called The 100 Videos , and yes, there were a hundred of them. They were chatty and smart and beautiful and seemed to contain every conversation I had ever wanted to have. And while they might have appeared overbearing, like an unwanted house guest who soaks up all the conversation, they were “only video” after all, and their numbers made a luxury out of them. He also didn’t mind failing. Oh look, he’s fallen right on his face, and then he gets right back up and knocks out another killer picture. He raised the bar for the art form and granted permission at the same time.

Then there is Steve, the person. I remember rushing over to Steve at some late night swarm with a friend in tow and we both gushed about how much we loved his work. He looked at us like runaway lab specimens. And while he has warmed to the idea of small talk in the intervening years, particularly with a martini or two in hand, there is something dead level in his bearing. Somehow, without running off to a cave for most of his adult life, or holding his body in improbable poses for hours at a time, he manages to exhibit a winning detachment.

Jason: You describe the grain of Steve’s voice in the introduction to his interview in Practical Dreamers, too. How did that voice become the voice in Auden’s head? Is it the voice you always wanted, too?

Mike: The Steve Machine is a machine in the form of a book. I had always wanted to make useful art; videotapes that could be strong enough to tow cars, but light enough to serve as the bow on a boy’s birthday present. After becoming positive, Auden travels to Toronto where he meets Steve Reinke, who slowly but surely shows him how to build a special kind of machine. This machine is not capable of towing anything, instead it swaps the interior voice of the reader for Steve’s cool elocutions. Most insider soundings are a jumbled sandwich of past and futures, while this voice, with its wide open spaces and easy handling, returns the gift of the present.

Jason: In the introduction for Practical Dreamers and in several places in The Steve Machine you touch on the idea that film and video art works may have miraculous healing qualities (or at least be useful as weight-loss tools!). Do you think many artists (including yourself) harbour this hope that their work could contain this magical potential? (i.e., that what they’ve made is not this grubby, flawed, misbegotten thing, but a talisman with the power to transform the audience in some literal way.) It strikes me as a common and probably useful delusion for artists lest they be consumed by the futility of it all…

Mike: In her Dreamers interview, Paulette Philips relates a moment in her art school class during the last federal election. She proposed that art was as important as health care, and her students were dutifully scandalized. 30 years ago they would have been tuning out and turning on, this year it’s all about jobs. Art is a conversational backdrop, an extra for people who have evenings to spare, a potential diversion after doing time in the money playpens downtown. Or?

But anyone who doesn’t believe in magic has never seen Kent Monkman’s painterly reworkings of the Western, or the fine trick Richard Fung pulls off in Islands where he takes his uncle, an anonymous extra in a Hollywood blockbuster, and turns him into the star. Artists movies are a place where someone else’s garbage is routinely turned into happiness, and most of all, where we learn to change speeds. What is love, after all, but changing speeds with someone at the same time?

Could I offer a small, often repeated example? If you take a glass already filled with water and hold it in your hand, how heavy is it? It might be a question of time. One minute, no worries. An hour later and that glass feels like you’re holding up a swimming pool, ten hours on and your arm needs surgical replacement. But if you put the glass down, even for a few moments, when you pick it back up again it’s lighter than ever. Art is like putting the glass down.

Jason: Another notion in the book that I found very compelling was the attraction we have for systems, machines and mechanisms that we hope will rid us of doubt, uncertainty and all the messiness that comes with free will and human frailty. Why does Auden need the Steve Machine so badly? Is it fair to say that he ends up processed by the machine rather than consumed?

Mike: Yes, Auden has been processed, filtered, recombined. Like the virus which will never leave, some encounters mark him, ready or not. His landlord, his boss, the bus driver, the people he meets at the orgy, they are writing on water. They make a fleeting impression and disappear. But when he finally meets up with Steve Reinke, he is startled to find someone whose voice is the one he hears while reading.

Do you remember that strange moment in Augustine’s Confessions? After a thrill ride of maxed-up intoxication and sexual oblivions, he retreats into the bible and reworks his life as if he were an actor learning a part. He doesn’t read, he absorbs and becomes the book. Along the way he stops at a monastery where, late at night, after the penitential prayers and ritual floggings, he retires to his chamber and begins again to pore over his precious book. One night he notices, to his astonishment, that a good part of the order has massed outside his door. They look at him in horror and amazement, because while he was clearly reading, he was not reading aloud. How could the words exist if they were not voiced? And of course, because the book he was reading was the bible, the voice that he kept to himself, the voice he gathered inside, was the voice of God.

“I look at the machine and think of a world where each memory could create its own legend.” (Chris Marker)

Steve Reinke is not God, but Auden needs him just the same. There is a way out of his illness endgame through a kind of “talking cure,” a machine built out of words. In the doorless rooms we sometimes find ourselves in, it is rare that someone else might have a key, or offer clues about leaving that impossible place. And rarer still that we might be open to hearing them.

Jason: I think Practical Dreamers and Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada (2000) are extremely valuable (and readable) as forums for fringe filmmakers to describe how they do what they do. Why do you have such a strong compulsion to deepen people’s understanding of an art form that can make poetry (to paraphrase the joke in The Steve Machine) seem like the daily news?

Mike: I don’t need to be the only person eating that special ice cream flavour. You must share the same feeling yourself, Jason, spreading the word in weekly installments about pictures which make new pleasures possible. The two interview books pull the curtain aside so you can see how the thing works, and why someone would want to do that in the first place. Over and again we read how some personal catastrophe (like love, for instance, or racial profiling, or walking home to find your father dead on the couch) puts the artist outside the general hum, the usual traffic flow. It’s not so unusual, it happens to everyone of course, but some make a home here, and begin to create new shapes for their experience. They may not be recognizable at first… wait, wait, what is that? But these small pictures allow us, invite us, to be larger than ourselves. They keep on showing me that the good candy doesn’t have to be hoarded, because there’s lots more where that came from, in new, impossible colours. How can you resist?