Too Late: an interview with Tom McSorley (May 2007)

Tom: Mexican poet Octavio Paz used to confound his publishers by constantly revising his poems, even after they were published. For Paz, the poems were never finished texts, as the contours of their expression were constantly reshaped by time’s passage. Is there a single, fixed version of Fascination, or is this film (and all your films, in a sense) mutable, revisable, unfinished?

Mike: I sometimes long for publishers to confound, a public turned in different directions, scholars forced to walk the long shelves again in search of a missing version. But one of the joys and post-pleasures that arrive on the fringe is the ability to work without the glare of attention. Who can operate with grace on that high wire? Well, there are a few, but it will not be an obstruction that any of us here will need to contend with. We fall too comfortably between the cracks of cinema and art (these movies are not dramatic features hence not cinema, neither are they stillborn enough for art world intentions). To make a picture means holding out the hope of seeing it later, of seeing what is there in front of you at some other moment, and like many, too many perhaps, I often prefer the company of pictures over people. The pictures I am most likely to review are my own, and I do so with a growing sense of dread and unease, because five or ten or twenty years after their production new moments come to light, a scene which appeared fulsome and lovely and glowing now seems dull and uninspired. Not to mention the bad choices of music. In the old analog world these reworkings were a kind of heresy, cinema was accomplished with a stringent economy of means, there could be no mistakes, the real heroes only turned the camera on when some union of perfect light and perfect intention crossed in front of the lens. I spend my time groping in the dark, always in search. Sometimes the evidence of this search is satisfying, but more often than not I feel that my notes and sketches don’t have to be preserved, and as a result, I’ve withdrawn most of my doodles from circulation.

Fascination has elaborated this process of discontent, it premiered in Rotterdam in January of 2006, and I’ve been busy recutting ever since. It reemerged in a swollen version four months later to open the Images Festival in Toronto, and since then I’ve trimmed it by half an hour, and re-shot everyone in the movie. “Finishing” doesn’t mean going to the lab and paying thousands of dollars and having prints and opticals made. It means pressing a button on a computer. Recutting means opening up the timeline and shaving a few frames, not going back to your irate negative cutter. Fascination presently exists in an arrangement of moments, scenes, impulses and flows which are optimal, all of the puzzle pieces have been tried in every position and this is the very best it can be. But having watched it recently in Guadalajara I still find it exhausting, despite its considerably shortened length. Will it ever be finished? Has all this work been done so that it too might one day be thrown away? Sure, it’s possible. I’m thinking of posting it on the internet and inviting remixes. Work on the fringe is often completed by its audience, why not take the gesture another step?

Tom: Do Fascination ‘s assemblies, accumulations, montages of moving images and sounds constitute, or suggest, a grammar of memory? The obscure codes of our mechanics of memory?

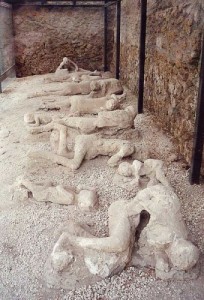

Mike: I am just back from what is politely known as a viewing, a word which has fallen out of common usage enough to be reserved for the dead. When I arrived in the small cave of an apartment, Mirha was still upstairs, preparing herself. I was met by Xanthra, a friend, who recognized me but, as usual, because I have spent my whole life not viewing at all, I didn’t recognize her at all. In a few minutes Mirha came down the stairs and announced that we would be opening the coffin, but first it was necessary for her to speak about what had happened, and then she re-enacted her first moments on Thursday morning, when she woke and came down the stairs and saw her partner Mark standing straight up near the foot of the stairs, and she wondered why he should be standing in such a posture, and it was only when she came near that she saw that he had hung himself with the leash of their dog.

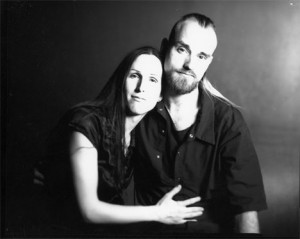

Mark Karbusicky edited Fascination , how many hours we spent in the dark, poring over pictures of Colin Campbell, adjusting and readjusting the orders of recollection. It was a trip that seemed to have only a middle, only endless and proliferating possibilities, and so we seemed “finished” over and over, until the next test group of friends and familiars would arrive and express new and unexpected confusions. How long does it take to get to know someone? When I arrived at their apartment, just a few hours ago, Xanthra said that no one had any idea that things were so difficult for Mark. What kind of pictures are we busy composing?

Mirha says that Mark’s uncle committed suicide and I find myself grasping onto this fact, I want it to make sense, I want to bring order to this violence. How kind he was, and what intelligence he brought to the edit table, and how magnanimous was his good humour and fine attitude. He and Mirha have been together for ten years, and were going to get married on July 15, her birthday. Two months away. They weren’t going to exchange rings but vowed to wear small necklaces with cat charms. They were animal rights activists, and kept a dozen stray cats at home. This afternoon Mirha put a necklace around Mark and then had her surrogate mother(s) put the other around her neck. Then she lit a candle, which was going to be the candle lit at their wedding, how much they had planned in advance already. And there they were, the couple, with their gold chains in the candlelight, in the middle of the afternoon, with the giant coffin taking up most of the living room and the flowers all bunched behind. Open so that we could see Mark’s beautiful face.

What kind of pictures are we busy composing?

Mirha asked me to read something this evening, to say something about Mark. This is what will be said (too late, not enough, this is all there is).

Mark and I spent many hours together in the dark, looking in the same direction, looking at pictures. For the last six years he has been coming with me to Charles Street Video and editing my movies, which are known most of all for their editing, which is Mark’s contribution. I think this role of editor is very typical for Mark, which allows someone else to realize their hope, while he is very quietly in the background. Working. He was always working. An editor brings together moments which seem impossible, or part of very different worlds. An editor has a sense of how these different moments might fit together, belong together after all. An editor has an eye for what is held in common, qualities that are shared between people or events, which seem far apart. The editor is the first one who can recognize this, once they are joined oh of course, it couldn’t be any other way, but before Mark puts it together, it’s so difficult to imagine. It’s a way of working, but also a way of living in the world, of seeing these connections, of living these connections.

For the first few years Mark would always arrive with a large knapsack, which would contain either two cans of Jolt Cola, or a single large bottle of Jolt Cola. There was a little variety store down the street and I think he bought every bottle of Jolt Cola they ever ordered. Long sessions meant three cans. He drank every one as if it was the first.

There’s one other person I know who shares Mark’s talent for relentless optimism. It is so consistent that I realized quickly that this is something he’s worked on, the way others would work at making a perfect cup of coffee or working out a blues lick on the guitar. Almost every day I saw him Mark would offer some cheerful recipe, he applied it the way you applied a bandage, and he did it so often and so well that it gave me a hint of a darkness that was all his own. It was a darkness that required tremendous diligence and watchfulness, and the fact that he was able to do it with such lightness, the fact that he was able to turn his own darkness for so long into something positive, and affirming, I really marvel at it.

He was so large and capable, it just seemed like he knew how to do everything, and if there was a problem it was only a question of time before Mark, who so very rarely exhibited impatience or frustration, would offer another way of approaching it, and he would cheerily tell me not to worry, he would be able to fix it, and he always did. Mark was always busy fixing things, and smoothing out difficulties.

It wasn’t until I saw Let’s Get Lost by Bruce Weber, that I could look into the wasted face of Chet Baker, and feel the pain that lay underneath all those sweet beautiful songs, the pain that made those songs possible.

The last time I saw Mark was in my apartment, sitting in the chair where I spend most of my life in front of the computer. We had finished this very very long journey of a film, and he had always been urging me not to work at the co-op, but to work at home, alone, by myself, the way he did it, even though it meant that I wouldn’t be hiring him for my projects anymore. For all those of you who knew him, I think you will recognize this gesture right away. There was never any thought on his part that he might be losing something, so he came to my place to give me his editing software, and he put it on my computer in that typical, very thorough, very careful, Mark way. He insisted that we boot up the program and use it, and then close it and then start it again, so that we could both be sure that it would absolutely work. He has been a model of kindness for me these many years, a kindness, it seems, that he was able to extend more easily to others than to himself. I miss him very much.

Tom: Tarkovsky’s famous dictum that cinema is sculpting in time is, of course, appropriate in the context of Fascination . If a life and its remembrance/reconstruction can be thought of in this way, what informed your hand as a sculptor?

Mike: Perhaps what we spent the past couple of years doing, Mark and I, was arranging the way that Colin could be forgotten. How do we forget the ones we love? Perhaps we’ll begin with a breakfast, or a parting wave on a day like any other, or the way he tied a handkerchief to keep his ears from burning on an afternoon turned suddenly hot. Movies are more commonly understood as time capsules, sites where memory can be frozen in an eternal loop (I was going to write; “Play it again, Sam” then remembered that this line never actually appears in Casablanca, though many remember it that way). But it is a commonplace, even for the specialist audiences that frequent fringe screenings, to catch a bit of the news or a motion picture bonbon on the internet before retiring, within a few hours of a fringe movie. In short, the experience of pictures is quickly supplemented with new ones, the rush is on, and we are in it, and all too soon that elegant montage which took months to construct frame by frame is just so much mental detritus, tossed along with the unwanted emails and grocery lists and last month’s momentary urgencies. But to give an orchestration to this forgetting, to imagine that it too has a shape, well, perhaps that is only a last gasp from someone unwilling to let go of the possibility that this too can be controlled and refined and articulated. Pass the control freak. Can’t we script everything in advance?

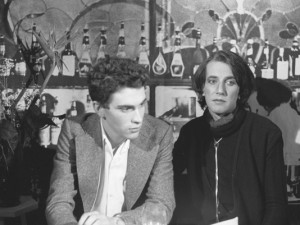

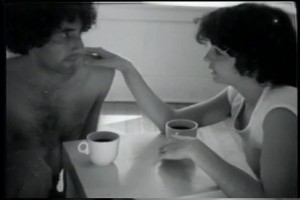

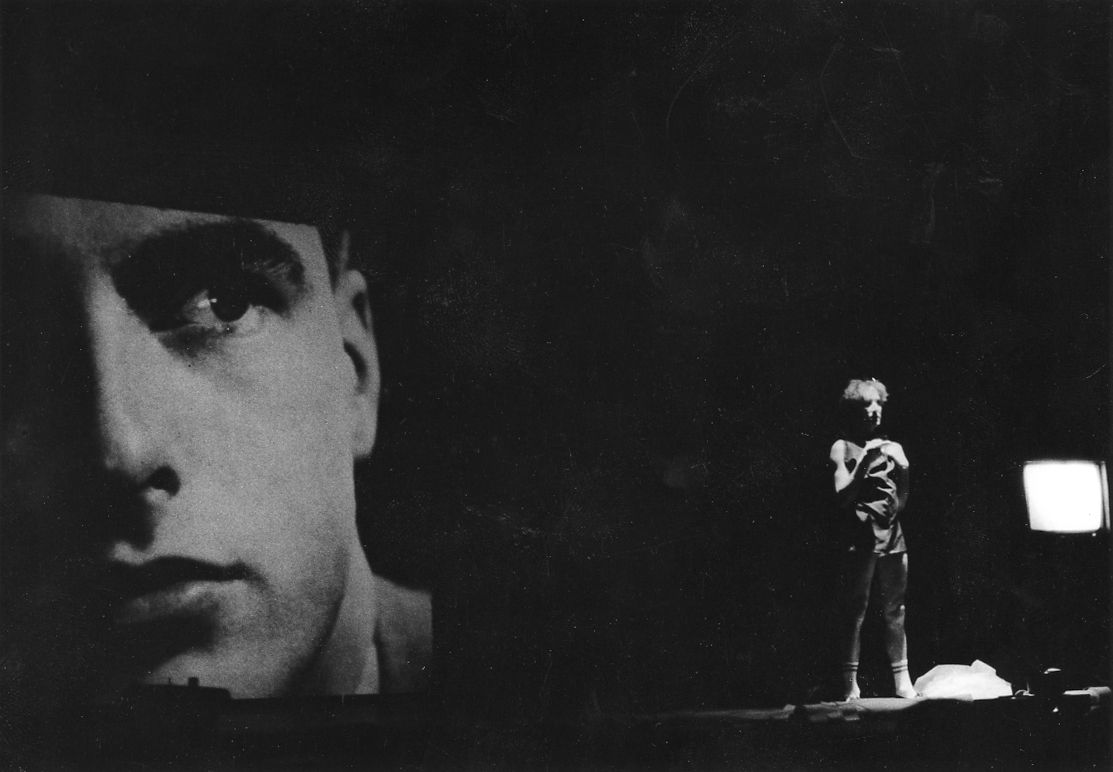

Certainly Colin was no stranger to scripted interludes, over and over again he recast his overlapping love lives into video art. This is how John Greyson put it at Colin’s memorial, this is only an excerpt, but it offers a taste: “In the early eighties Colin Campbell was professor in residence at a little-known, yet extremely influential atelier: The Woman from Malibu’s Video Art Academy and Finishing School (Yonge Street Campus, upstairs from the Athlete’s Foot outlet). Ten easy lessons, non-accredited. No tuition, just intuition. No transcripts, just trans-sex. No prior experiences necessary, just start making tapes-or martinis. Between classes he was variously producing Bad Girls , Modern Love , He’s a Growing Boy , She’s Turning Forty , Dangling by Their Mouths , Conundrum Clinique , White Money . Lessons invariably overlapped with production. As did life.

Lessons

1. Turn last night’s dinner conversation into tomorrow’s dialogue. Colin’s scripts were flagrant collages of his pal’s best bon mots and intimate confessions. We’d emerge from screenings both chagrined and flattered by such blatant thievery. And grateful, because he’d tightened our timing, improved our delivery, deepened our meanings.

2. Make nightclub sets from couches and lamps in the studio. In turn, make couches and lamps from display racks that the Athlete’s Foot outlet downstairs left in the alley last week. The same corner of the loft, the same Athlete’s Foot “couch,” the same lamp-are featured in every tape he made in his place on Yonge Street, yet they always seem new and different. Five-minute makeovers were effected with a swath of fabric, a coat of paint, a backdrop of pastels on coloured paper.

3. Shoot with one or two or no lights, one or two or no crew, one or two or no backdrops, but always two or more drinks. He was hopeless with tech yet he’d find his unique way to make it work. His best shots were sometimes when he forgot to turn the camera off. His best edits were often the ones he made by mistake, his best montages the ones he slammed together deck to deck.

4. Assimilate high theory and low humour by osmosis. Colin never read Foucault and Deleuze; he didn’t need to, he had friends who did. He just inhaled the gist over dinner, unerringly extracting the curds from the whey. He shoplifted from both sides of the culture promiscuously: headlines, Edie Sedgwick, gossip, trash talk, Barthes, then transformed his theft into unassailable ownership. His tapes are very op-ed, of their moment, a catalogue of tabloid obsessions and current debates. He found uniquely personal ways to respond to political crises, be it censorship or AIDS. Though he was appalled by injustice in any forms, his interventions were never from the soap-box; he refused the rhetorical in favour of ironic commentary.

5. Write roles for old friends because they need cheering up, and for new friends because they need unpacking. Video as socialization: who cares if friends can’t act? The raw, jarring, awkward and at times excruciating gap between the person and the performance was the space he zoomed in on. Colin was allergic to verisimilitude, fascinated instead by the vulnerability of self-consciousness.

6. Monologues are more interesting than dialogue because they don’t pretend to be natural. In Dangling by Their Mouths he quotes the dead-mother monologue from Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying at length. In tape after tape he returns to Faulkner’s strategy of competing monologues, different characters confessing their versions and secrets and poor little poems to the camera. The first movie we saw together was Fassbinder’s In the Year of Thirteen Moons . More than anything, this film helped me understand the art that Colin was chasing, embracing, creating. The art of declamation, the art of melodrama, the art of tableau.

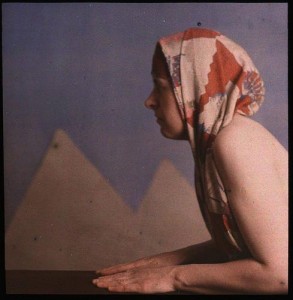

7. Tableau. The art of waiting for the thing you don’t expect to happen, to happen. The art of composing a body within a box until the frame cracks and the performance breaks and some sort of truth seeps out. Often a truth spoken by.

8. Women. Colin was unthinkable without women, fascinated by women, incapable of not identifying with women. Such empathy carried risks of hubris, of misunderstanding, risks he deemed willing to venture. He’s the only person I’ve known whose friendships (deep, profound, intimate, long-term) were truly transgendered. Which meant that he resolutely refused to let gender define anyone. Which of course made him a very queer enigma that neither Church Street (gay town) nor College Street (trendy town) could fathom. (Queen Street-the art scene-did him somewhat better.)

9. Bad drag. Bad drag is better than good drag. Bad wigs are better than good wigs. Bad drag skips the surface and slams you right into the hunger of gender, the ten-year old boy with the towel over his tits in the bathroom mirror pretending to be Elizabeth Taylor, terrified of being caught. Which brings us to 10: narcissism. Video as mirror, camera as confessional, the screen a pool of mercury: darkly beautiful, tremulous, on the verge of wonder, on the brink of tears. Only a narcissist as unflinching as Colin could stare into the lens with such honesty, and see himself so clearly. And know that through such a mirror he could see us.

(The Singing Dunes: Colin Campbell 1943-2001 by John Greyson. A version of the above text was presented in a tribute to Colin Campbell at the Power Plant in February 2002. It was published in C Magazine in 2002.)

Tom: Does Colin Campbell’s ‘performed’ life and works represent in some fashion that beguiling paradox of intimacy inhabited by cinema/moving images/technologies of communication? (eg. moving images seem to bring us closer while, in their very material construction, push us back) Does your work inhabit this paradox of intimacy? If so, does it like the neighbourhood? Does Fascination differ in this regard from, say, Tom?

Mike: Tom is my friend, and our meetings (invariably just the two of us in his postage stamp apartment) are replicated in the movie I made (which Mark also edited). I have left out master Tony his Brooklyn amour, his nightclubbings, his gym time, the caregivers that provide live-in help, and Clark, his long time on-again-off-again boy friend. When Tom and I see each other the white light spreads from his Cheshire smile and we speak from that illumination, often I am audience to Tom’s prodigious feats of memory and eloquent articulations. The movie about Tom accompanied him, it was shot over some years, and we spoke about it often, sharing different cuts and material. There is an intimacy in the movie which arrives out of the time we have known each other. The pictures may seem far away, sourced from hundreds of anonymous places and woven together in a dreamland of possible frames, but Tom’s voice anchors the experience, and we return, again and again, to a moment of his body, the movie touches him, is touched by him, and then is sent back out into the world of pictures. It moves in and out of this embrace slowly.

Colin was never my friend, so its intimacy register is very different.

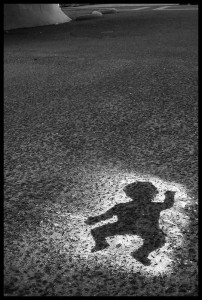

Put very simply: I arrived too late, before I began the movie he was already dead, and this lateness shadows every moment of this recounting. There would be no way for him to speak for himself, for example, or comment on the movie as it developed. In place of the missing centre there was an expanded field, a coterie of friends and familiars who I slowly visited, and who each weighed in with their very different impressions of Colin. Standard doc practice requires a series of sit-down interviews where they would tell us, the unknowing, the strangers, what he was like. They would deliver him to us (as if he were something which could be delivered, which could finally be made transparent and understood). Do I even need to add that standard doc practice, like the narrative fiction upon which it’s based, also tries to seek out a root cause (What childhood occurrence, endlessly refrained, could account for his relationships, his decision to become an artist, his life?) What I hoped to do instead was to make a picture of Colin by filling in the background, by tracing around him, permitting his ‘figure’ to appear in relief. His friends would provide that background, and I imagined that if I could conjure a suite of mini-portraits of those closest to him, then he would rise up out of this choir.

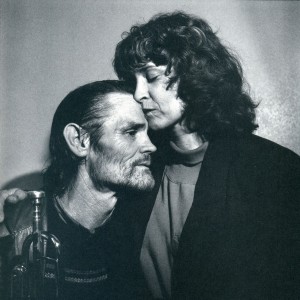

I started with George Hawken, his long time lover and best friend and keeper of the estate. Like many of his intimates, George appeared in several of Colin’s videos, and these personas are shown in rapid succession in Fascination, to underline the notion that the picture is a mask. As Oscar Wilde said, in a line that is quoted in the tape, “Give a man a mask and he’ll tell you the truth.” George talks about death and sex, the way Colin looked at himself when the end was near, and how he couldn’t see his own beauty, only fear. He also speaks about his own desire, “The thing that he figured out about me was this weird conundrum I have where if I really want something I say I don’t want it.” Colin is able to read the mask of desire (not “going behind” the mask, or taking it away, but allowing it to demonstrate, in a complicated fashion, what it may seem to hide). George is taped in Colin’s last apartment, still filled with much of Colin’s furniture. Who is the ghost, and who is the haunted?

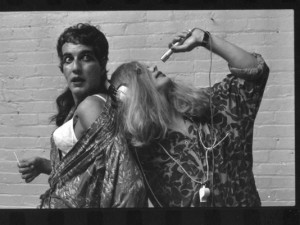

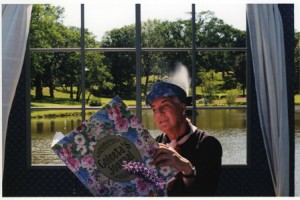

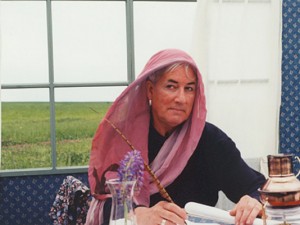

The performance artist Tanya Mars, on the other hand, is shown in a clip collage of personas from her own work, and the work she made with Colin (he shot her first videotape Pure Virtue (1985), where she appears as a fire breathing Queen Elizabeth. By presenting these clips we are seeing what he saw). She very kindly agreed to enact a small performance for me, dressed in a swank lavender ball gown, she destroyed a van with a sledgehammer. This occurs while a clip of her speaking plays from the touchstone feminist document I am an artist, My name is… by Elizabeth Mackenzie and Judith Schwarz. In this tape made in 1986 they gathered 102 women artists who speak about their practice. Tanya’s strong feminist stance is physically enacted here, and once this moment of character is established a series of pictures follow (snaps of her and Colin, more performance stills) while she speaks about the way they spoke together. The image track shows us what Colin would have seen, the soundtrack offers a reflection on Colin’s hearing, though it is also Tanya’s hearing. The subject is dispersed, offered in fragments, moments, lines of flight.

Do these pictures bring us ‘closer’ to Colin? On the one hand I wonder why we need to get so close, so often I see documentaries which have hardly begun and there is a massive close-up of the subject, talking of course, telling what they are unable to show. And I can’t help but wonder: would any of us in the audience stand this close to a stranger on a subway? Movies of course are designed to give us an intimate distance, the safety of the movie theatre allows us to enter worlds and faces and lives we would only be repulsed by in ‘real life.’ (Or is our ‘real life’ also made of pictures?) I am not hoping to deliver the subject, to make Colin accessible, open and knowable. Mark’s death, for instance, created many questions: why did he commit suicide? Why didn’t I try harder to reach him? How did the circumstances of his life lead, like the vanishing point in a Renaissance picture, inexorably, inevitably, to this tragic end? There are hints and clues, difficult relations, money worries, but in the end there is the mystery of Mark, the way he cannot be reduced to a moment when he was fifteen and rolled up his purple bell bottoms and danced all night to the Rolling Stones. Or that trip he took to New Zealand and the people he met there. They don’t line up like soldiers to produce an army of facts pointing to one necessary conclusion.

Tom: Fascination has insistent water imagery. Talk about your use of natural imagery (landscapes, skies, seashores), including water, into the work’s other insistent themes of media, representation, and technology.

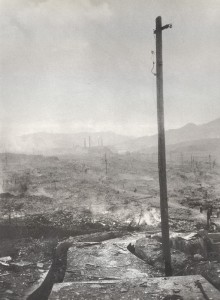

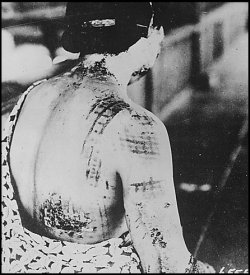

Mike: Strange that anything should appear in this movie except for brick and concrete, given Colin’s urban(e) personality and my own apartment existence. But the movie is framed by pictures of Colin in the desert, in the western imagination a site of wandering and exile, fourty years for the Jews and as many days for Jesus. It is a place of trial and visions and searchings (like this movie, which sets off in search of its subject, but never finally arrives home). The promised land (the transparent subject, the warm and comfortable Colin, the one we can get to know from the safety of our easy chairs, as his friends explain it all away) is deferred and abandoned. This desert is also the place where American missile tests are held, an atomic warfare carried on right at home, against its own citizens (in the name of science’s permanent war, what matter that communities are exposed to lethal doses of radiation?). This testing lays waste to everything around it, after the smashing of the atom, the smashing of the landscape, and all the people in it. Colin was drawn to this place, and by framing the movie with its blank expanse, he is refigured as a child of the bomb, condemned to wander in a desert which has been created for him (and for us).

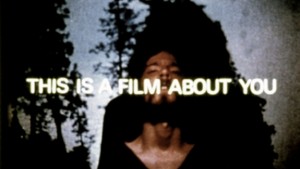

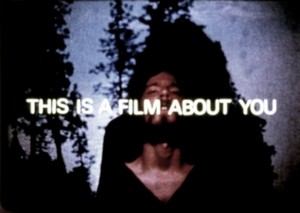

The first picture of water arrives a little later, clipped from the original Frankenstein movie. A scientist has created “a monster,” which is taken in hand by a young blind girl. She is innocence personified, and treats him not as a monster, but another person because she doesn’t know any better. And of course he responds in kind. For this moment, blindness is seeing, and the desert turns to water. In voice-over, across this picture, I have recast the lines of George Landow (now Owen Land) whose movie Remedial Reading Comprehension features an image of a man running in front of a rear screened projection of the woods with titles emblazoned across his chest: “This is a film about you/not about its maker.” In this sequence Landow/Land rejects the first person cinema of luminaries like Stan Brakhage, finding it too self indulgent. He prefers to examine the mechanics of the medium itself, how do we know what we know. In my movie this polemic is rewritten via reception theory. “ I’m going to ask you to create your own picture… Because this is a movie about you, not about Colin Campbell… In other words, a biography of an artist.” So there it is, baldly stated, the secret aim of this movie, to “convert” its audience (conversion is a dominant theme in Landow/Land’s work), and ask them to become artists via their reading of this movie. What is being conjured in this desert of pictures is the possibility, the hope, of a new kind of subjectivity which is able to hold two opposing ideas in mind at once, thinking in stereo. Like Berger’s attempt to instill a working knowledge of Russian grammar into the teen argot of A Clockwork Orange , I have tried to create a movie which could be read (or seen or listened with) “in stereo,” from two channels at once. This follows from the idea of Colin as a “stereo artist,” one who refuses the dichotomies of the cold war (us versus them, freedom versus slavery, the missile gap…) by being able to hold two apparently contrasting thoughts (he was both male AND female). He is a stereo artist because he creates pictures which look back, in other words, he joins the look behind the camera with the one in front of it. These two looks meet at the plane of the camera, or the screen, or the audience, and it is this meeting which produces a picture. I’m trying to argue that pictures don’t simply appear in viewfinders and billboards and newspaper adverts, these are mostly visual noise or camouflage, of the kind the state specializes in producing. In opposition to state pictures, and broadcast lies, artists like Colin are producing small, narrowcast pictures using a variety of means, though it’s no simple task, the approach Colin takes to producing a picture involves this double vision, this second sight.

But I seem to have wandered far from questions of landscape and their deployment.

Carolynne takes a picture while standing in front of a lake, there is a drive through night rain, snowy walks which Khrushchev tumbles through, an icy patch which I fall onto, a pair of Italian landscapes (Colin spent summers there, towards the end), Colin on a grassy hill being struck by lightning, John Wayne shooting Natives on a river, and then in the snow, sunlight in trees (taped in Amsterdam after I heard that David had cancer), the young girl and Frankenstein again (this time as Churchill uses the words “iron curtain” for the first time, heralding a Cold War alliance, imagine the Frankenstein of communism, differently treated…), John Greyson at the beach, a young girl walking the ruins of Hiroshima, Lynne Fernie in her sun drenched back yard, Niagara Falls, Tanya Mars firing a gun in the snow, Lori riding her bike by the water and finally Colin in the desert again. It has taken time to gather these almost pictures, seasons have past, and these compressions and expansions and openings are on offer to those willing to make the trip.

Tom: In conceptualizing and realizing your work, Fascination included, do you borrow images and cinematic sequences the way, say, in music Keith Richards appropriates Chuck Berry riffs or passages from older blues musicians? This, it seems to me, has always characterized the ‘musical’ structures of your works. Or at least the effects of your work on me, emotionally. Please talk about this as it relates to the ‘state of pictures’ in Fascination .

Mike: It’s difficult to imagine a look in the movie house which arrives for the first time, when the stars enter, when the light rises up into those perfect faces, hasn’t the way been smoothed and prepared for us, aren’t we only looking again, and again, at what has already been seen? The camera guides our looking, and we look through it, or look again. And the way the camera looks is itself coded (how do we see what we see?), there are “correct” positions and distances which must be taken towards the subject, inscribed again and again. Am I immune to these backstories of looking? Hardly. My work for the past half dozen years has been spent largely in the edit room, recasting pictures already made, trying to place them into different arrangements so that new stories could come up out of them.

Take the idea of “ending.” There is a certain feeling “we” get when a song is about to end. Yes, that feels right. Yes, it’s OK if the movie finishes now, or else: no, that went on too long, that didn’t feel right at all. How do “we” know that an end is approaching, and who are “we” anyway? Does this change over time, the collective pressure of this looking, the way cinema (or TV) gathers up so many looks and concentrates them in one place? Mass production produces the mass.

Fascination ends with an image of Colin in a car, on one side, contained and constrained in this small vehicle. But behind him is the desert, a black and white blank, an infinity of space. The camera is held up close and moves across the dashboard slowly, so that we feel the effort it takes to get this close to him. And it’s important that the camera is being held by Lisa Steele, his lover at the time, this is also what allows the camera to be close, it is an earned closeness, it doesn’t simply arrive, it isn’t only a matter of putting a camera down and saying here’s a close-up, but of living this close-up first, and then telling the story. So the camera is close, and Colin waits on the other end of the look, looking back. Over and over again Colin looks back from the picture in his work. And once the camera gets to him he doesn’t start in right away, instead he waits, and waits some more, waiting for our look to settle, for us to catch up with him, and then he says, in a line which might summarize the experience of the moviegoer, or the movie itself: “I too have unfulfilled desires.” And then he looks away from her, from the close-up, into the distance of the desert, and even though he is right there, he isn’t close any more, he’s gone. He shows us how far away someone can be, even though they seem so close. He is looking to the desert for some way to say that, to express that impossibility. The movie ends as he becomes the distance he looks at. It is a gesture borrowed from the original, Lisa Steele’s The Scientist Tapes. But before that, this look, this knack of being far and close at the same time, the way Mark could have been so close to me during our edit sessions, and yet at the same time so far away, perhaps even, is it too much to say, so far away from himself at times, this kind of looking had already been laid down long before, and we are only replaying it with a camera, and a car, and a desert.

An interview with Eduardo Thomas for the Ambulante Festival December 2006

1. What would you say is the role of documentary films within the contemporary context?

There have never been so many documentaries made, from the digital home movie to the proliferation of magazine-style news programs on television. Even television drama has taken a turn towards the documentary with “reality” based programming. And owing to a few blockbusters (by American white men Michael Moore and Errol Morris) documentaries appear with increasing regularity in the movie theatres. Once relegated to the small screen, people are now willing to pay to see them, at least some of the time.

Here in Canada we have a long tradition of doc making, in part because fledgling fiction film production was snuffed out by the Americans. The Motion Picture Export Association is an American organization formed to ensure that the theatrical monopoly they enjoyed in many countries around the world would be maintained, and this well monied and influential group regularly “negotiated” with foreign governments (various attempts by successive Canadian administrations to increase domestic production of fiction films by, for instance, imposing a production tax on movie goers, were foiled). Faced with the prospect of a very modest production push, the Association forced the Canadian government to withdraw all funding, in return for setting up the National Film Board, which would be dedicated to documentaries and animation, two forms of movies which didn’t threaten the American monopoly. (There were other, more dubious provisions agreed upon; mentions of “Canada” would be written into feature film scripts as a desirable location, presumably to stimulate tourism.)

All movies, large and small, bear some relation to the imperial project of pictures. To keep spectators in the dark, and then to illuminate them, to light up ideas and demonstrate lifestyles, what an attractive and necessary force this has been for the movement of capital. But alongside these relentless depictions of the ruling class there have been a proliferation of other cinemas, counter cinemas, some of them fictions, others documentary. What is the role of the documentary? To show us that other lives and dreams are possible, to be able to approach the Other with the necessary distance, and to demonstrate, via montage, an ethics in motion, to produce a moving demonstration of ethics in the relations between picture and sound and between pictures.

2. In your opinion, where is the border between documentaries and experimental documentaries?

For me it is a question of form. Most documentaries are produced for television which requires a certain transparency: oh, I know what you mean! There can be no doubt, no mystery or ambiguity. As a result, very few pictures appear in these documentaries, because a picture, a real picture, often produces illumination and mystery in equal measures. What takes the place of pictures in the television documentary? Words. In the mouth of someone like Godard, words are also part of a project of producing pictures. But in most documentaries words are a way to tell and not to show, to shirk the duty of pictures, to get around the force and impact and responsibility of pictures. Words are used as a cover up, so no one will notice that the frame shows us again and again a fear of looking, or a confused looking. There are so many images but no pictures!

“Experimental documentary” is not a phrase I would use, though it has been applied to my work. I don’t feel I am “experimenting,” for instance, my edit room is not a laboratory, my viewers are not test subjects.

Because these movies, which I like to call fringe movies, are made, for the most part, without producers, without a destination already determined, they can be free to follow their subject. I have been listening a lot lately to Miles Davis for instance, and last night I watched a documentary about him. But as usual, there were no pictures of him at all, only talking. I thought that the best way to make a documentary about him would be to create a film without pictures, or without sound. Could you imagine a jazz movie entirely without sound? That would be fabulous. Miles was a radical (“to the roots”) musician, a black man in a white America, with a restless nomadic disposition. In order to arrive at a place where one could hear the hard softness in his ballads, the cost of appearing so vulnerable in the macho club environs where he made his living, some shift would be required in the usual viewing mode.

Mainstream media produces an infantile viewer (you sit back, we’ll feed you, we’ll do the work), just like mainstream medicine (doctors are experts, while you, the patient, are the passive recipient of knowledge). This extreme division between expert and know-nothing breaks down in the fringe, where viewers are asked to take up a role as a producer of pictures.

3. Why do you use found footage and archive material in your work? What is the value of these materials for you?

When I was a child my parents made snapshots of me performing traditional childhood routines. When I look at them today I realize these pictures are absolutely indistiguishable from thousands of others. Here documentary is already fiction, what I (and my parents) had imagined as singular and unique moments (it’s my life, mine) were only poses. I had allowed “childhood” to enter me, to occupy me like an invading army. And in turn I dutifully performed childhood, I played the part, and then adolescence and adulthood followed. How had I, along with so many of my peers, managed so easily?

An aside: at the turn of the last century the average lifespan for a north American male was thirty years. Hard to squeeze in an adolescence when time is so short. The creation of childhood is made possible by many factors, and pictures are amongst them. Pictures entered my home, they entered me, until I became a picture as well. These pictures continue to surround me today, not content to be “everywhere I look,” they have become the way I look, they make possible my looking, because I am looking as a picture, the world is already “framed,” “camera ready.” Without this frame there is only an incoherent jumble of impressions. In order to grant meaning to what I see I need to look a particular way, and this is the first and greatest importance of pictures. They teach us how to look.

So what about the use of stolen pictures in my work? I believe that my own personal artifacts, “my” snapshots and home movies, are already found objects. For instance, when I applied “autobiographical” moments via home movies in the elegiac closing section of Panic Bodies (70 minutes 1998), I freely mixed the home movies of myself, friends and strangers. No one can tell the difference, because, as I wrote before, I was only one of many people who were busy performing childhood. Our home movies are interchangeable. I could be someone else, I have already been other people, led other lives, and am looking forward to leading more soon. You only live twice says the Bond movie. If only it were that simple.

The boundary between what is mine and what is not mine is fluid, in part because of the way pictures make an orifice of the body. Pictures open the body, make it susceptible to other picture viruses, which seize control of the body, telling us what is beautiful and what is ugly, leading us towards the nature of desire itself. These pictures, which were never made by me, but which are received by me in the most profound fashion, are somehow also “mine.” It’s my favourite song, my favourite rock video, they’re mine, and in order to tell my story they need to be included.

4. Under which criteria do you edit your work?

I have been a persistent re-editor of my work. Unlike most makers, whose oeuvre continues to grow each year, mine grows smaller and smaller. Almost all the work I produced between 1980-2000 has been removed from circulation. This is not important work to anyone but myself, and there is no need to inflict it on anyone. This withdrawal is also a kind of “editing.” Of the work that remains much of it has been re-edited, sometimes long after it’s been “released,” (this is a very relative term in the fringe media world, where the presentation of these moments can be very modest). House of Pain (50 minutes 1995) for instance was initially 90 minutes long, and recutting meant going back to the negative cutter and remixing the sound and striking new prints. I did this years later, knowing that hardly anyone would ever have the opportunity to see this new/old work. But each work has a particular momentum or trajectory which needs to be recognized, and best of course if that can be followed and understood instantly, but often it takes time, sometimes years and years, before the dizzying thrall of making can dissipate enough so that one can see what is really there. The act of projection doesn’t occur only when a work is finished.

5. What are the boundaries of a biography within film?

The movie I’m presenting at this year’s Ambulante festival is called Fascination (70 minutes 2006). It is a sideways biography of Canadian video artist Colin Campbell. What a typical movie of this sort would offer would be reminiscences from friends and lovers (borrowed intimacy), and some experts would be called upon to offer testimony to the artist’s genius and importance. It would follow a chronological line, sources of inspiration would be laid out, and some primal moment of discovery or trauma would be unveiled so that all of the artist’s work could be reduced and understood through this simplifying frame.

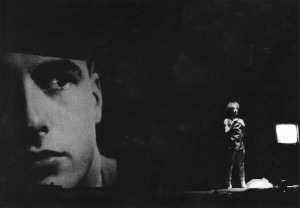

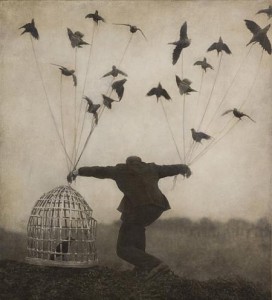

But I was interested in other things, for instance, the idea of a portrait as it has existed for many years in the fine arts. I began visiting drawing classes and saw people make drawing after drawing trying to achieve a balance of line and gesture, using the weight of the pencil to produce some sharpness which might express the jutting of a nose or hip. In all this they are trying to make an approach, and mostly, they are failing. They try to come up with a resemblance, but these are only attempts. There is something so beautiful about this, the video camera does exactly the same thing of course, most of the pictures which run over the play heads are not pictures at all, they are only attempts, botched deliveries, unfinished pieces of looking. But video offers a smooth surface, and so can easily fool the person behind the viewfinder. It is much more difficult in video to tell whether a real likeness has been achieved. How to produce pictures with this difficult tool? That was part of my task. And of course I had arrived too late, Colin was already dead, so there was no way I could try to produce a picture with him. But on the other hand, Colin was one of those rare people with a dozen best friends, and a legion of close confidantes and intimates. So I began my movie with the task of trying to find the face of some of these folks, that’s all I wanted to show in the movie. No one would say a word about Colin or about anything else, they would simply show the face that Colin looked at. I would need to wait until their faces would open, I would need to see them again and again, the way those sketchers went through sheet after sheet of paper. The movie would present a succession of faces looking at you, the viewer, the way they looked at Colin, in effect turning “you” into him. Three years and many re-edits later, it has become a very different movie.

Mike Hoolboom /Mieka Bal talk moderated by Lisa Steele (Images Festival, April 2006)

Lisa Steele : Good afternoon, my name is Lisa Steele and I’m the Creative Director of Vtape. I’m very please to be invited to moderate this conversation between Mieke Bal and Mike Hoolboom, but moderating a conversation sounds adversarial, so I don’t know, if I have to get in between them I will. First of all I’d like to thank the Images Festival for again being the catalyst for bringing artists and audiences together. It is always a pleasure to be associated with Images. Special thanks to Scott Berry, Chris Kennedy, Jeremy Rigsby, and especially Christina Battle who has coordinated all the installation projects for Images this year. On behalf of Vtape, I extend my sincere appreciation to Pam Edwards, who’s at the back, and the board of directors for A Space and the volunteers and staff here for so graciously presenting the additional installation, Nothing is Missing by Mieke Bal, throughout the festival. Working by email, Pam and her volunteers created a sweet and very intimate setting for the mother’s stories to reside in, and I encourage anybody who hasn’t seen it to try to experience it after the talk. It will be here throughout the Images Festival until the 22nd of April.

So our speakers today: Mike Hoolboom is an experimental film and video maker, a writer, an editor, and active, indeed an activist, within the Toronto arts community. He is the author of two books, Plague Years in 1998 and Fringe Film in Canada in 2001, which is in its second edition now, and he’s edited several magazines and books. He is a founding member of the Pleasure Dome screening collective and has worked as the artistic director of the Images Festival and the experimental film coordinator at the Canadian Filmmaker’s Distribution Centre. He’s won more than thirty international prizes and has been the focus of retrospectives in eight European cities. His work is also celebrated locally, as we saw last night for the premier of Fascination, his moving portrait of the artist Colin Campbell. Artistically, Mike’s work is the very essence of the project that seeks to reclaim the imagery of the twentieth century and name it as our own. His portrait works, Jack and Tom, both from 2002, and arguably the best work about having sex while listening to the CBC ever made, Frank’s Cock in 1993, all display his virtuosity with montage, his humour both touching and dark, and his ability to speak the personal within the context of the political.

Mieke Bal is an incomparable scholar whose credentials, awards, publications and books—her CV is twenty-two pages long, indeed, too numerous to detail here today, if we are to have time for any discussion at all. So briefly, she’s written critical texts on visual art and artists including Caravaggio and Rembrandt and literary figures such as Proust. Her scholarly work is wide-ranging in topics: semiotics, cultural theory, memory, feminism, and the Jewish Bible, to name just a few. She is a professor at the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in the University of Amsterdam, and a founding director of the Amsterdam School for Cultural Analysis. But today, Mieke Bal has joined us as an artist. For the past few years she has turned to the moving image, producing often within a loose collective structure entitled the Cinema Suitcase, a group of works that elegantly and structurally address migration, movement, immigration, emigration, refugees, and now with Nothing is Missing, which is on display here, a work in progress from 2006, the faces of those that migration leaves behind most often, the mothers. Minai Anjou: a thousand and one days , from 2004, tells the story of a young North African man living in Paris whose wedding had to be postponed. Access Denied, from 2005, examines the friendship and family of a contemporary Palestine émigré living in Amsterdam who returns to Gaza. In the hands of Mieke Bal and her collaborators, the layers of meaning, experience and histories, individual and cultural, seep out, filling the time-based words with the skin of lives as they are lived, messy, rich and unresolved.

To begin this conversation, I want to ask each of you to address your own work through your choice of form and how it fits the content of the works on view here at Images. I’m thinking particularly about how both of your projects— Fascination, Mike, and, both of the installations, Mieke—are portraits, but the forms that you’ve each employed are initially frustrating to the viewer. They deny the pleasure that is normally ours to be had from a linear story, and why you chose those particular forms for the content that you have.

So I would ask, first Mike for some words, and then Mieke. And then I know you both have questions for each other and comments.

Mike Hoolboom: Fascination is framed by pictures of Colin in the desert produced by a pair of Colin’s intimates. Firstly there’s a home movie of John Greyson where he and Colin return to the site where the woman from Malibu, one of Colin’s many characters, has disappeared into the desert. John’s footage is playful, very much a home movie but set in this beautiful, epic landscape and Colin looks fabulous. John’s camera, like every camera before him, loves Colin. Cameras always seem to find Colin in the right light, at the right angle, he is always camera ready, and this is combined with the feeling John brings to his pictures. I see you. Don’t you see? I can really see you now.

Fascination opens with a pan towards three camera operators, followed by a triple exposure, as if we were watching the accumulated results of this looking, which shows Colin as the woman from Malibu (already multiplied, not one self but many), and then we watch him/her walk off into the desert intercut with military men in the same desert. He is joining them, examining what they’ve done, choosing to live in the world of the cold war military and the deserts they always leave behind. But it’s not until John picks up a camera that we see, clearly, an image of Colin in close-up. It’s the feeling that John brings that makes this close-up, this recognition, possible. The close-up doesn’t simply arrive, it’s earned because of the feeling between the two of them, which is shown, the picture which is shown is also a picture of this feeling, this closeness. A picture made not taken.

And at the very end of the movie, after a lot of wandering and digression, Colin appears again in the desert. It is a shot lifted from The Scientist Tapes made by Lisa Steele. Colin is sitting inside a car parked in the middle of the desert and the camera makes a pan across the dashboard to his face. It’s important that this pan is made by hand, that the camera is handheld, because it emphasizes the muscularity of this shot. The camera travels slowly in this small distance, showing the weight and effort required to close the distance between the two of them. In this shot Lisa produces a close-up, and just like the earlier close-ups by John, this is a view that is earned, it represents the space between these two people. I am with you, I am this close to you. Often one can watch on television some unmet stranger filling up the screen with their face. Who’s that? These pictures provide the illusion of proximity while maintaining distance. But what is delivered first by John and then by Lisa are real close-ups. In both instances they make an approach. How does one make an approach? How can one find a place from which to see this face? This is the question that is taken up, again and again, in Fascination. Picasso said, “I don’t search, I find.” But Fascination labours with none of his certainties. It is a movie in search of its subject, in search of an approach.

Most documentaries assume that our lives are knowable, intelligible, transparent. Often they reveal a formative trauma or revelation which is echoed across an entire life, providing a satisfying unity. Especially when someone’s life is shrunk down to an hour and a half. Closure, aka the feeling of “the end,” arrives, ideally, when the viewer knows “everything” or at least: enough. But perhaps our lives are not structured like movies or books. Or at least: not like most books. But this movie doesn’t pretend that Colin is so transparent. This movie is adamant about maintaining something of his mystery, his opacity, the fact that there may be aspects of his personality which might be foreign even to himself.

Fascination is framed by scenes of the desert, an old motif in Western literature and art. It’s the place of being lost, the site of exile and wondering and so provides the central motif of this movie, which has a centreless centre. It wanders geographically from Sackville to Toronto to Amsterdam to London to the south of France. From the war in Vietnam to the living rooms of his friends. And over and over again it tries to conjure Colin. Where is he? While he appears often he keeps sliding and slipping as he shows us different aspects and personas: the innocence of Robin, the knowing confidences of Colleeta Sackville-West. This accordion personality unfolds and comes back again. Early in the movie there is an excerpt from an early, seminal work by Colin called True/False where he says, “My name is Colin… true…false.” So already, there’s a double take. Is he or isn’t he?

Lisa Steele : Can you talk about the way you use montage?

Mike Hoolboom : The middle of the movie, the thing that goes into the sandwich of the desert. I hoped to raise this question: how do we make a portrait? I was thinking about people that spend their whole lives trying to make portraits in a more traditional way, for instance people who like to draw. I began attending life drawing classes, not to look at the model, but to study the way people looked when they sketched. There’s a brief scene in Fascination which shows this looking. People gather in a room around a central figure, or an object, trying to get their muscles to move the way their eyes are seeing. They might start a drawing of the same person ten times. They might draw all night and then throw it all out. The most important lesson I learned was this: the image doesn’t come right away. The portrait doesn’t arrive instantly.

Now that’s tricky for me, because I lack any real skills I rely on video cameras to create pictures. The camera has its own optics and magnetic tape encodings . So when I turn the camera on that thing over there, that subject, appears in the viewfinder. Look, there it is, right? But I think that most of the time, what appears in the viewfinder is a placeholder. It’s where the picture would be if there were one.

While we seem to be surrounded by images, most are a kind of visual noise or static. Whenever you walk down the street there’s a riot of passersby and exchanges and traffic of every sort and if someone stopped you on the corner of the building we’re in and said, “OK, you just passed eighteen people on the last block, could you describe anyone of them? Would you mind drawing a picture of a corner of your living room with every little object in it?” Could you do that? Where is our attention exactly? So the question of how to make a portrait is troubled by the tool I’m going to use. How to use this tool, this camera, to get all the way over to the other side where my subject is. Perhaps, after all, I could use this tool to show how to make an approach. How I might make an approach to Colin.

Two and a half years ago I began speaking with some of Colin’s many, many friends. Colin was one of those people who have ten best friends. And how much more satisfying for an audience it would have been had I taped some of their incredible recountings and stories. Sitting in the big easy chair telling when Colin said this and Colin did that. As if the past was an easy thing, transparent and graspable. As if you, a perfect stranger, could sit in that easy chair and have it all come to you, as if you had earned that place of closeness. That’s how most biographies proceed. As if we weren’t, each of us, a mystery after all, as if there wasn’t something deeply unknowable about each and every one of us, and as if this mystery, this darkness if you like, wasn’t the heart of the matter, the very thing which needed to lie at the centre of our biography, even though it couldn’t ever be pictured, or even admitted. Somehow I needed to use my very imperfect tools to conjure this too. That meant that when I visited Colin’s friends, mostly I did it without a camera. They wanted to talk and I wanted to listen and that was great. That was for me, but for not for this movie. The work I did with his friends was to conjure our encounter, our meeting. The movie isn’t nostalgic in that sense, it sits in the present, and tries to wait for the place where their face opens. I am an odd person in the lives of these people, even though we hardly know each other they speak to me about very personal matters, with great intimacy and trust. Please remember that I’ve come to them not immediately after Colin’s passing, but some years later, they’re not talking about Colin all the time anymore, except when I come around. And with each of them there’s a point at which their faces would open. I felt this was the moment when they were seeing Colin again. Or to put it the other way, it’s the point at which Colin is seeing them. It is the face they presented to him, and my task, as a would-be biographer, is to be present, with the camera rolling, at the moment their face opens.

This was my preposterous, perhaps utopian hope: that I could present to you a number of people who were very close to him, and show them at the moment when they are seeing him again. I have suggested that what they are looking at is Colin. In the movie theatre, what they are looking at is the audience. They look back at the audience who “becomes” Colin in these moments. Fascination tries to conjure a different kind of subject and subjectivity by displacing its centre, and thereby recentering its viewer.

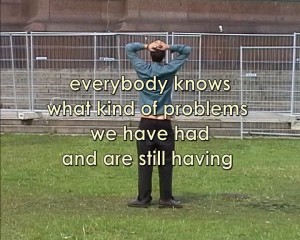

Mieke Bal: It’s a great pleasure to be here, and I’m thrilled to be here with Mike, whose work I admire deeply and Lisa and Kim and everybody here. I’m very attached to the work in this room, here behind you, this little living room with screens of women who are talking about their children who left. Upstairs in Vtape you’re going to be able to see, starting tomorrow, the film Lost in Space. With Lost in Space we’re trying to bring to visibility something that could be described as a portrait of a situation. The situation is that of displacement, and that displacement, it turned out very quickly, ruptured everything that you could pin down. That’s what displacement is. We started the film by asking people to talk about what it meant for them to be in displacement, or to work with people in displacement, or to have no home. And something happened during one of those interviews that determined the form of the film, which is that one person just couldn’t speak, his English was very limited but he did want to speak. He insisted. We thought we shouldn’t use him because his English wasn’t good enough and that already is a very problematic feeling. But he said, I really want to do this and he did it. I asked him, ‘What did you miss most about your home?’ He was thirty-two and had been an asylum seeker for sixteen years. He was from Iran so I asked him, ‘What do you miss most’ and at that point he was unable to speak. So I said, ‘Say it in Farsi, later I’ll understand what you said and I’ll be able to put it in the film.’ More silence followed and suddenly he burst into Farsi and what is he saying? What he most misses is speaking his own language. So, it became a film about language because that was clearly a big issue for this man, who had the most difficulty speaking. And so, the whole form of the film became rigorously out of sync. That’s what it is. So first we show the people talking but you don’t hear them and then you hear what they say and you see it transcribed/translated on the screen and then the images just don’t match. That’s basically the form and we tried to make that a radical principal of critique of the predominance of English, as the international language and the inequality that is built into that predominance. Probably most of you here have English as a first language or at least as some language of ease and it’s really hard to understand what it means if you don’t have that. Yet, it’s the only way to live. Day after day, they have to live with that. So that became the principle.

Now, the way that plays out in the film is that the first two minutes show the people with some street noise behind, in the background. After that you see images of what I call the state of stagnation which is also the state of emergency of society today–images of the futility of unemployment, of security measures trying to protect the embassies in Berlin and not really managing. At another point you see workers trying to put out a fire but the house is destroyed because there are holes in the pipes and the water is going to the passer-bys and not to the house. Anyway, you’ll see this and tomorrow we will talk more about it.

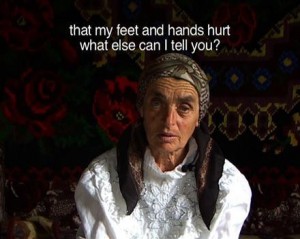

Now with the mothers in Nothing is Missing, the idea was to go and look at the other side of this situation. What do they leave behind and what kind of loss is that? Again here, the portrait is really the form, and the idea was to bring to visibility a situation where individuals suffer major loss. There is nothing more poignant than people who raise their children, then watch them go without knowing if they’ll ever see them again. But more than that, to have to be happy about it, to have to say I’m so relieved she’s gone because the bombs are flying over my head and she’s safe. I’m so glad that he doesn’t suffer from revolution—that he could go to school. I’m so glad that she’s not being raped and beaten up in the house. So these mothers are celebrating their own grief and that paradox is, I think, under-illuminated in discourse in the so-called host country where people end up. So I wanted to go and find these women and see what they had to say. Now, the process is very important in this case, I wanted them to talk in real time to someone who’s very intimate with them, but also in a sort of interrupted relationship due to the migration of the child. For example, the son-in-law who is actually the reason the daughter never returned, or in another case the daughter-in-law who the mother didn’t get to chose—which she would culturally be doing otherwise—or the grandchild she never saw. In each instance there is a family member with whom the relationship has been interrupted but also has some sort of natural appeal to her. So then I turned on the camera and left. I hope you will be sensitive to that sense of intimacy. I did not want to be an intruder. I did not want to have control over what she would say. I gave the relative who was speaking to her questions that she could or he could possibly ask if he was at a loss for questions, but what I wanted to happen was that she would talk about the child that had left—and that was the only assignment, so to speak.

So I turned on the camera, and left the room and came back after about half an hour and the most astonishing things had happened during that time. I’ll give you just one example, the woman in Tunisia speaks to her daughter-in-law who she had never selected for her son. The daughter-in-law is second generation, born in France, and a little insecure for that reason. Also, because everyone says, “Oh wow, he is such a hunk,” and “I’m not pretty enough.” So she is talking to the mother and the mother is talking to her and it’s all going very well and she is reminiscing about the baby that he was, and the child that he was, and the day he was born. Then, suddenly, the daughter-in-law says, “When you finally saw me, what did you think?” No answer, something else, distraction. After a while she says, “But no, what did you really think of me?” She keeps insisting and ends up saying, “Did you think I was plain, ugly, a loser?” Now, that’s pretty strong, right? And the mother, in a moment of silence that makes you really sit on edge to hear what the answer will be, looks aside and she looks back and she says, “I thought you were beautiful.” Now, what happened here is something that empowers both these figures. The mother gets to give her approval, after all. And the daughter-in-law receives the approval she hopes for.

You could call the filming a documentary, in the sense that it’s document, because it’s not fiction, but that is an opposition that we all know is problematic. But what you document is not what happened before. What you document is creating what happens and so it’s the result of the documentation rather then the reason for the documentation. In each case, there is something that happens that would not have happened without the documenting, and that for me is very important, as part of what I wanted to do, which was to make a tribute to these invisible women who sacrifice everything to raise their children, and then have to sacrifice the child for their own well being. I wanted to do it without sentimentalizing them or bringing some major condescending pity to these women because they’re also happy and have a rich daily life. But, I think, there is a major loss that needs to be acknowledged, and for which the West has some historical responsibilities. In that sense, I think it is really important that they get to do it, and the performativity of the process was really important.

Mike: How long are shots of the mothers?

Mieke: Anything between twenty-two and thirty-five minutes. I could only cut the beginning and the end because I did not want to mess with the image. I had to let it take its own time.

Mike: I was wondering if you were concerned that this two hour presentation occurs in four shots, and that people might find this overly long.

Mieke Bal: Well, whose talking about length.

Mike: That’s true, my movie is long, but that’s why I choose a movie theatre where it’s difficult to leave whereas it is normal to wander in and out of art galleries. This wandering means that these voices may be visible but not heard.

Mieke: I really believe in the freedom of it all. I’m not so concerned, because I’ve been watching people going to this thing and sitting inside—and what happens is when you enter it, you’re surrounded by a cacophony of voices, none of which you understand. Then you sit with one, the other voices recede in the background. Now, you can sit with one and do the whole visit, or you just enter at the moment when she’s just talking about something like a normal visit and you stay twenty minutes or you stay an hour. That’s up to each of you. I think that very quickly you get drawn in. It’s easy to leave in the first two minutes. It becomes hard after ten minutes to leave. That’s one of the things that I really pursue in my video work. As a critic of art, I have always been very disturbed by the critics, people walking through the museum as if it’s a race and only looking at the labels. I think that’s a consumptive attitude to pictures which is based on the misunderstanding that you can see the picture in a glance. Text needs a lot of time and pictures you can see in a glance—but it’s just not true. You’re just not seeing it. I’m sure there is some work to be done to make people slow down. I think the virtue of art and art galleries is that people actually suspend a little of what they were doing the rest of the day. I’m hoping this piece will have that effect, and you actually enjoy visiting women that you would never have met before. I may be overly optimistic but that is my goal.

Lisa: Mieke, your Lost in Space requires translation, even the English speakers have their words appear in subtitles. Mike your strategy is to talk overtop or between speakers, I’d like each of you to speak about strategies of layering text and voice.

Mieke: Lost in Space presents the translations in subtitles rendered large over the image. The translation itself becomes the image and the image is the background. Moreover, everything is translated or transcribed, including the English. The primary reason for that was that some people speak better English than others but they should all have an equal chance to be understood. The interesting thing is that when you transcribe a native speaker of American English, you realize that they have just as heavy an accent as someone trying to express themselves in German or Turkish. There are mistakes in translation. There are situations where we had to give a little more credit to the speaker because the transcribing is so unfair. You pick up what they say with the mistakes and the incorrect grammar but if you leave the mistakes in the text, it looks like they can’t speak properly, so you have to correct a little bit while others are left alone. All these decisions make not only for a linguistic community where English is just as accented as other languages, it also makes the complicity of the maker very clear. You’re making all these decisions and that is very obvious. People ask me sometimes, “Where are you in this project?” Well, I’m all over the place. I try not be bossy, that’s all. I try not to have control. So, this guy who couldn’t say what he wanted to say and he turns out to be speaking about just that, he determined what the film was going to look like. But I was making all the translations and that is where my hand is, so to speak, in addition to the editing and the sequences you built up so that statements arrive in the right place, and images in the background get to the right place. For example when the guy starts to talk about not being able to go back to Palestine, that’s when the images of the firefighters gets wobbly. It’s exactly at that point it gets out of hand.

Now with the mothers, this was even more gripping because after the taping I come back and ask, “Was it OK? Yes? Do you want to see it?” Then I show it back to them on the television if they have one or on the camera. They could actually say I don’t want this. In one case the woman starts to cry heavily in the middle of it and this is a very rational woman who didn’t mean to do that. So I asked her do you want me to cut that which would only leave half its length but she said, ‘No, every mother would cry.’ Their approval is important because it’s their voice and they have the right to remain silent. But then I had to translate, I had to bring someone in who spoke their language—and I started to translate with the person who did the interview, and there is never enough time. Then there are questions of how you do subtitles, of how to separate the sentences, how you have to distort a little for the length of sentences and the size of the screen. Only afterwards did I understand what had happened—and that sense of belatedness, that “the image comes always too late,” is part of the process of translation.

Mike: One of the great things about Lost in Space is that the viewer sees all the people that we’re going to hear later. The tape begins with a parade of faces accompanied only by their names and I thought, of course, as an installation work, this is it. It’s just going to be twenty minutes of faces and names from all these different places and we’ll have to imagine all the incredible stories they would have told. Then the voices begin and because of the separation between picture and voice, somehow it’s easier to hear them. Many of them speak about being disadvantaged because of their new circumstance but without their pictured accompaniment, because we are ‘only’ hearing them talk, there is a necessary suspension of judgement, a certain kind of judgement that can’t begin to hold on to these speakers. I thought it was a very ethical way to present these people.

Mieke: That was actually a very important element. If we had matched the faces of the speakers with their voices, you would have an incredible problem of voyeurism with some of the people. I think that with the homeless mother of children in Ohio, there is a kind of identification, a bit of a life’s story, but then if they are going to speak: “What I do wrong is…” then it becomes problematic. So it was indeed an ethical issue, and to have some equality among them in spite of the very different situations among them; for instance someone who is in London because they are a professor of film studies is really in a different situation than someone who is in their own home town but in a homeless shelter. The difference is important and I don’t want to erase it, but we didn’t want to individualize it. I don’t want to de-politicize it by making them all equal. They’re not equal, and that’s clear from what they say, but it’s important that they are not considered with judgement at all as individuals, in the sense of individualism, but rather as individuals in a situation. It’s important—the situation. It’s a very serious issue. Now with the mothers there was an issue of translation that has to do with literalised metaphors. Sometimes a metaphor is so important to keep like the mother who says, “I’m glad he left because he now has to eat.” That would be one way to say it but what she says is that he has bread. Everybody goes after the “bread.” People need the “bread” and that word “bread” isn’t even metaphorical. It’s this elementary food and keeping that literally in the translation makes it possible to have the resonance of the poetry of the language, but also to reflect on how easy it is to make it a little easier to digest. Sometimes I needed to keep the structure of the sentences rough, not smooth.

Lisa: Mike, are you going to answer that question?

Mike: I could try.

Mieke: I could read one of your sentences and maybe you can respond to that: “Here is the image as camouflage as it fails to offer itself to the light of meaning.” Do you remember that sentence? You wrote it. What does it have to do with image?

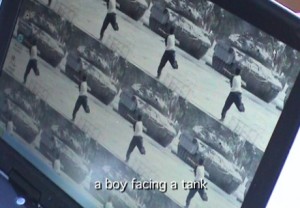

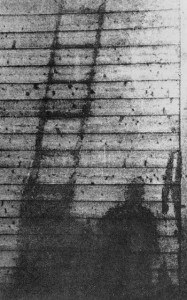

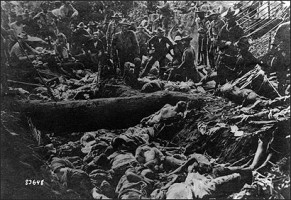

Mike: There are three main through lines in the movie, some are working better than others right now, I’m still in the midst of rethinking the montage, and will go back to work on it soon. One of its themes is the atomic bomb, dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, then tested in the American deserts. The quotation you cited belongs to Maurice Blanchot, and I applied it to the image of the bomb. Why is that? When someone says “atomic bomb” a mushroom cloud goes off in my mind, it’s the picture I share with everyone in the room. This consensus was state imposed, created and disseminated by the American government to hide the war crimes it had already perpetrated. The mushroom cloud is a picture created to disguise the atomic bomb, not to show it.

But perhaps, you might argue, they had no pictures to show. But that wasn’t the case either. They didn’t drop one bomb, they dropped two. Why? Because they had developed two kinds of bombs, and they wanted to see how they worked. And after they dropped the bombs they sent in camera people who arrive in the hospitals. Can you imagine a foreign power wiping out Toronto with an unthinkable weapon, and then showing up to film the results so scientists could examine its effects? This footage was censored, along with any mention of the atomic bomb, as Fascination points out, even children’s books were scrutinized for any word of the event. It simply didn’t happen, because the victors always get to write the official record, the history. Never mind how many people died, atomic destruction was “off the record.” That’s why after the attacks on 9/11 the twin tower site could be named “Ground Zero” by the Americans. There was another Ground Zero which had already existed for five decades previous: the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But “we” never did that so it doesn’t exist. This is also part of the cover-up legacy that is contained within these pictures of mushroom clouds.

Camouflage (the image that looks the other way, that points in the wrong direction) is a very common use of motion pictures, pictures are routinely shown on nightly newscasts for instance which don’t manage to show anything at all because the people making them don’t know how to look. How often have we seen pictures from Palestine which never manage to show what a simple diagram or map will illustrate, that the Palestinian territory, as proposed in the Camp David talks, or as constituted today, is not contiguous? It is not one territory but divided and controlled by Israeli roads and checkpoints. A simple map begins to show the oppression of the occupation, which all these pictures of buildings and roads and scarves and ballot boxes do nothing to show. They’re showing something, but it’s not an image, you can’t really see what’s going on. It’s not an image made to reflect so that you can understand what’s going on. It’s simply narrating a flow of erasure showing the same kind of camouflage at work. The insistent focus on world leaders, the president said this, the foreign minister said that, is often not news at all, as we learn very quickly from reading history books, much of what the present government says is an absolute lie. The stage managed disseminations of world leaders rarely provide pictures, despite their wide dissemination.

State sponsored and corporate imagery often take this form: as things which look like pictures but which aren’t pictures. They are only distraction. In opposition to these state non-pictures stands an art practise of individuals, narrow cast not broadcast. One of the reasons that video art begins with a relentless focus and examination of the body is exactly because it has been repressed for so long, covered over in a nuclear cloud.

There are many counter-practices that exist, other ways of imagining or producing the picture like Colin’s who makes small, very intimate pictures. Using modest means and small screen delivery, he often works with his own appearance, delivering his direct address to you, the viewer. It’s me and it’s you. His tapes also narrate a counter-practise of time, a chronopolitics of resistance. His work requires a different quality of attention for a different kind of story. His long shots and stories allow us to reflect on the fragmented stories which surround us (which feature cutting but not montage).

Audience member: I just want to make a comment. Metaphors are supposed to deepen understanding. Increasingly the objective of art is to move audiences past the flat-line of TV where objects are removed from history or systems of meaning. You’ve both chosen practices which take us to another place.