You are Not Yourself: an interview about The Invisible Man by Alan Stevenson

Alan: You’ve shown your work mostly in movie theatres, whether in festivals or as one-night stands in the local fringe house. The Invisible Man is your first solo outing in a gallery frame, what’s the difference between the white box of the art world and the black box of the cinema?

Mike: The cinema conjures the most temporary of communities. For the length of a program the first person turns into the third. “We” look together, sharing the same darkness, surrounded by the same sound, facing the same picture. It is a collectivity marked by time-for some duration “we” are in it all together. This collectivity is both troubled and pronounced in the work of the fringe. These marginal movies typically attract a specialist crowd who, because of the history of their looking, are already a community. Oh, it’s you again. And again. Fringe movies are also a hang out, dating combine, social service. What else to do on a Friday night in the geek kingdom? This is the way “community” is underlined in the fringe. Here’s looking at us. But. The third person can be undermined by the movies themselves which typically fail to drive to a point, which don’t gather up every last street corner and wayward glance into a story which resolves, at last, when we know everything. When this narrative striptease is surrendered, when movies are constructed as digression or as an open field in which audience members are invited to wander, it is possible to leave the theatre with profoundly differently experiences.

I remember watching a Rose Lowder movie which consisted of single frame shots of a tree. I learned this later. She had painstakingly circled this tree, changing up exposure and focus twenty four times a second. When she was done she constructed an elaborate printing chart which ran this negative through different filters in patterns, again and again across the same length of film, until this single three minute roll was a sixty minute movie. Or at least that’s what she told us later. I didn’t see trees, what I experienced, dumbfounded, awestruck (and sober) was the entire history of representation. It was a shuddering, shaking, quivering procession of history (without sound!), with wars and people dying and displacement and epic journeys and loves lost and won and lost again. Then the artist stood up and talked about a tree. A tree? I was speechless. How could it be? My eyes, those generally reliable regulatory filters of the visible had created a trip that only I had taken, though no one in the theatre, as far as I can remember, really had much sense of what we were looking at.

Most fringe screenings don’t run quite as far in dividing its audience, nonetheless, the real hero of fringe movies is the audience. What else to call those who can weather Andy Warhol’s silent multi-hour stare at the Empire State Building? Or Mike Snow’s spinning camera for three plus hours in the Quebec wilderness, accompanied by occasional electronic bleeps? The audience is often asked to create their own movie. Here is the shared secret of artist’s film and video: that each spectator is also an artist, a creator. And each fringe movie shares, to a smaller or larger degree, in this utopian hope: that it might provide the ur-moment (out of boredom, or rigour, or an impossible colour) that will turn its audience into artists.

So what about the gallery?

The gallery has no shared time, folks enter it under their own steam, between laundry and a late lunch, or before meeting a friend, or while doing rounds of other galleries. Those busy absorbing art like to speak of the “art world,” a term which refers to that posse of the dutiful that see the world through the frame of the gallery, along with the coterie of marketers, producers, curators and writers that keep the frame floating. This can also constitute a community. Showing my work in a gallery has meant, sometimes, a get in for free card, entry into a specialized membership. I’m grateful for it, it’s always nice to be admitted through the front door, though like Groucho I’m skeptical of any joint that would count me amongst its members.

The biggest difference between the movie theatre and the gallery is the shared look. In the gallery people come and go, sampling the buffet, watching parts of some things, ignoring others completely, looking at moments again and again. But mostly browsing. There is no browsing in the movie theatre, in the gallery the shopping (do I like this? is it me?) never has to end. It was strange for me to see for the first time Manual by Matthias Muller and Christoph Girardet, a meticulously crafted work which splices together moments of 1950s hi-tech, especially reel to reel tape recorders, and offers a meditation on the cost of so much utopia. I had been looking forward to seeing it as soon as I heard it would be shown at a large museum during the five star Rotterdam Film Festival. I found it in a low ceilinged basement, there were some other things behind it, I can’t remember now, and I sat on the floor and watched Manual three or four times with a friend. Over the course of that fourty minutes there were dozens of people who poked their head through the door, but not one actually looked at the movie for more than a glance. Manual (which is about surveillance, amongst other things) had attained a kind of invisible visibility. It was showing all day at the renowned Witte de Wit gallery, which was helpfully located downtown, and there were hundreds of visitors each day. But how many managed to see the work there?

The conditions of a movie theatre speak of constraint, and the law (you must!), and prohibition (no talking, not too much shuffling around). The picture rules, and the audience has to be still in front of it. It is the most authoritarian of all the arts, it demands, and out of these demands it builds a consensus. It creates “us.” In the gallery these demands are released, and with it the notion of a shared view, and somehow I can’t help missing this. Another illusory arcadia to pursue.

I am moved to speak of “advantages,” to compare and contrast, to decide which is better, best, bested. But would prefer to feel that both gallery and theatre are simply different. What did my once friend Matthias write me in a letter? Am I ready, he asked, to swap the pettiness and lies and puffed up egos of fringe film and video for the pettiness, lies and puffed up egos of the art world? Oh yes. Oh please yes. Above all yes.

Alan: Why is the main character in one of the projections called The Invisible Man?

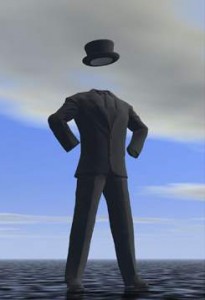

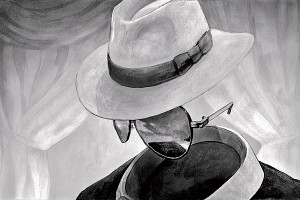

Mike: There are some people I can never quite bring into focus. I see them at parties or screenings but whenever I walk over I pass right through them. Are they really there? Of course they are. They are the background hum of my life and I provide the same service for many others. (How disconcerting it would be to have ride the metro each morning solo, or to be the only person in the supermarket. But could I draw the face of a single person I ‘shared’ a half hour commute with? Not at all, and I am grateful for that too.)

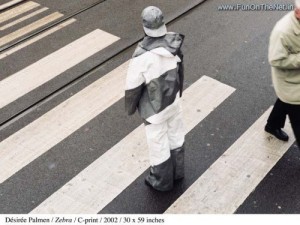

There are many ways to be invisible. To want what everyone else wants for example. The same jeans, the same boy band record, I don’t these things so I can express myself (It’s ME!) but instead to con form, to fit in.

The Invisible Man is committed to this kind of belonging. He has spent his life steadily emptying out his subjectivity. How has he done this? Hard to know, as the mid-section of his life is missing. We are granted pictures of a child and the middle-aged man he becomes, between them lies an abyss of forgetting, the root and momentum of his invisibility. This much is for sure: “he” is a motion picture construct, culled from a variety of sources, some well known, some obscure. Whether driving a car, taking off his jacket, wandering through the snow or washing his face, these pictures have arrived from somewhere else, they precede him, and now have arrived to occupy him, like an occupying army.

Roland Barthes writes about this in his celebrated essay The Death of the Author. Here he swaps the usual role of author and audience, claiming that it is only the audience that can absorb the many meanings of a text, the audience grants meaning and completes a work, while the author is the one whom language speaks. The dead author and the invisible man. The viewing situation of fringe movies, where the audience is raised to heroic heights, is this not the very condition that Barthes spoke about as already underway? The great author, the celebrated stylist, the international celebrity Roland Barthes, more alive now than he ever was, how many years after being run down by a milk truck? Invisibility was one incarnation he never managed.

“We know that a text does not consist of a line of words, releasing a single “theological” meaning (the “message” of the Author-God), but is a space of many dimensions, in which are wedded and contested various kinds of writing, no one of which is original: the text is a tissue of citations, resulting from the thousand sources of culture. Like Bouvard and Pecuchet, those eternal copyists, both sublime and comical and whose profound absurdity precisely designates the truth of writing, the writer can only imitate a gesture forever anterior, never original; his only power is to combine the different kinds of writing, to oppose some by others, so as never to sustain himself by just one of them; if he wants to express himself, at least he should know that the internal “thing” he claims to “translate” is itself only a readymade dictionary whose words can be explained (defined) only by other words, and so on ad infinitum: an experience which occurred in an exemplary fashion to the young De Quincey, so gifted in Greek that in order to translate into that dead language certain absolutely modern ideas and images, Baudelaire tells us, “he created for it a standing dictionary much more complex and extensive than the one which results from the vulgar patience of purely literary themes” (Paradis Artificiels). Succeeding the Author, the writer no longer contains within himself passions, humors, sentiments, impressions, but that enormous dictionary, from which he derives a writing which can know no end or halt: life can only imitate the book, and the book itself is only a tissue of signs, a lost, infinitely remote imitation.” (The Death of the Author by Roland Barthes, translated by Richard Howard)

The Invisible Man is also a “tissue of citations,” comprised of movie moments which predict and inhabit his actions. He doesn’t take off his jacket “like” Claude Rains in The Invisible Man (1933), he IS Claude Rains. It is the same jacket, in the same scene. But he is then jolted from this moment of re-presentation to become a boy on the stairs, and then Kevin Bacon from Hollow Man (2000), busy washing his face in a mirror which is unable to reflect him.

Alan: There is a three monitor stack enclosed in a dark casing which faces the projection, could you describe the contents of each of the monitors and comment on their relationships?

Mike: Why three? Perhaps it is the riddle of the sphinx: what moves on four legs in the morning, two in the afternoon, three in the evening? The answer, which turns out to have unexpected and tragic consequences in the tale of Sophocles, is very simple: man. He crawls, walks upright then takes up a cane. Similarly the three monitors relate to three ‘ages’ or times of a man. These three moments are literalized in the top monitor which was shot in Vila do Conde, Portugal. It is a wonderful town, part old world credo, part new Europe manufacturing outpost, filled at its centre with old men who stand all day on bridges fishing. They see each other week after week, yet hardly manage a word, standing patiently on one of the many bridges that criss cross the centre with their lines out into the water. And here is the most wonderful thing of all: when they are finished, they throw the fish back. Isn’t that fantastic? It is a gesture more luxurious, more perfect, than any I could imagine making. The next day they set out again, with the same resolute calm. To be devoted to such uselessness! They are model and inspiration. Also in Vila there is a large pier, a stone jetty that runs out into the water, leading nowhere of course, inviting villagers to take a stroll, to look out into the water already plainly visible by land, and then to walk back. There is no perfect or better view on offer, no point at all in making the walk, there is no other side, or advantage to be gained. This stone jetty is an echo of the fisherman, some of whom gather along its edge. I shot there one fine summer day, careful to frame only the empty blue sky. An old man walked into the frame behind me, slowly, very slowly making his way forward. And then from the other side came a much younger man, and I imagined them the same person, that he was coming to meet himself at two different ages. And then when they had come and gone a third figure appeared, a child on a bicycle speeding past, each age its own velocity, and all this occurred in an unbroken stretch of time.

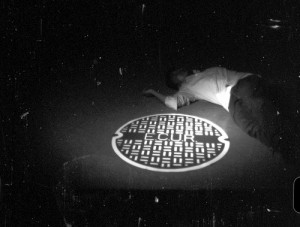

The bottom monitor was taped much closer to home. To get to my apartment close to the lake it’s necessary to cross a bridge which spans the railway tracks beneath. Each fall these tracks undergo after hours repair, and it is a beautiful, sad sight. A single man hauls a large welding machine along the tracks, sliding it up and down, checking each join and joist, alone in an immense darkness. These tracks are like a life, the long road of someone’s life, and these sparks seem to me, each time I see them, like those parties where everything is flowing, where the synapses are firing, where you are as funny and fulsome and witty as you’ll ever manage. You are firing light, and it may not happen the next day or week or for a couple more years, we undergo these dry seasons, where no original thought occurs, where we put little into the world, and so this worker trudges on in the dark until again he makes a spark, a necessary spark and proclamation of his living.

The middle monitor shows a seven minute loop called Last Thoughts , which is clipped out of a feature length concern called Imitations of Life (70 minutes 2004). It shows a man on his deathbed, with a raft of scientific instruments, pulsing organs, gloved hands reaching for cures. These are presented in impressionistic sequences, not the narrative of recovery but the delirium of a final giving way. This movie, while only seven minutes long, is my imagining of a second or two, no more than that, of a dying man’s thoughts. It began with something my friend Tom told me about his father, that when he was on his death bed in the hospital and Tom went to visit him he would often hum to himself, in those final days, the old child’s nursery rhyme: “Merrily, merrily, merrily life is but a dream.” “Where did all the time go?” he would ask Tom, his eyes wide with bewilderment. He had become again a child, much younger than his middle aged son who had come to visit.

(It is also related to a chat I had with Al Razutis about a surf he made on New Year’s eve, turn of the century. He had decided to see the turn occur while in the water, and set off from his Mexican beach house into the ocean to surf alone. After an hour or so he noticed a giant wave on the horizon, and before he could react it was on top of him and took him under, smashing his board. He was sure he was going to die. He washed up and then down again, and had time enough, he recounted to me, to go through all of his life, in fact, he assured me, there is plenty of time to run through every conversation and every relationship. The waves threw him against the rocks which he clung onto, as they receded he held on, though the rocks cut deeply into his fingers. He withstood the tide and crawled out, not dead yet.)

I took his “stream” imagery literally and produced a densely layered montage of water imagery, all flow and tide and undercurrent, and sank the dying man’s image into it, along with medical instruments, doctors and surgeries. Water, from this perspective, is also blood, water remains the largest single component of our bodies. In these final hours inside is also outside. What properly belongs outside the body (organs and blood) are held out for display. And the streams and rivers are also occurring inside the body. The body has become the world, just as the world inhabits the body.

There are repeated instances of drowning pictures, hands reaching for the surface, arms and legs kicking towards a never ending wall of water. It’s as if the dying man were drowning in his own body, or his own thoughts.

Childhood memories provide a primary accompaniment, as his immediate circumstances become less substantial, hold less meaning for him, his memories grow increasingly dominant, more real than the hospital. These childhood memories often picture children as shadows, running across sand, or swinging from swings, gathered in faceless groups, always in movement. Always opening. There are repeated images of a boy running (at night, in positive and negative, during the daytime), closing the distance between his younger self and older self, running towards his own ending, his own death. A man’s hand reaches towards his own face, as a young boy, positive and negative, as if he were trying to re-unite with himself. Last Thoughts is a lyric expression expressing simultaneity: of past (childhood) and present (death), gathered in a sacrament of blood and water.

The final images show the boy still running, children pressed up against hospital glass, and a cadre of school children gathered at a fence waving good-bye. As if waving good-bye to their classmate, grown suddenly too old to stay. The dead man floats past, the man is seen again in the hospital bed, and then the whole round of pictures begins again.

Three stacked monitors enclosed in black (like a tomb, or totem) face the projection of The Invisible Man. They are in dialogue, showing off for one another, on display. The monitor column could be the ‘backstory’ or pretext of the projection it encounters, its dark double and twin. These two facing pictures offer a fragmented mosaic of biographies which are composed, or de-composed, by memories and moments which are foreign to the body which houses it. The body is a surface of projection, but also a storage place, a container, for these media moments which are lodged deep inside, and deep along its surface. What remains visible of our lives (mostly not our memories, which are touch and smell and past visions, always changing) are bodies which hardly belong to ourselves, and whose gestures are echoes and mimes of actions already made by others, according to desires which come from outside the body. Together they suggest that invisibility is commonly held after all, the usual thing. The more we can see, the more often we present ourselves, the more invisible we become. How else to understand each other?

Interview with Mike Hoolboom by Bob and Marina Black

[Our conversation with Mike Hoolboom, which took place on January 28th 2005, lasted nearly five hours and covered a variety of topics, including some of his earlier films. Below are excerpts from that interview, which focused on his exhibition at the Art Gallery of York University.]

Marina Black: The Invisible Man is your first solo gallery show, how does it make you feel?

Mike Hoolboom: When Philip Monk invited me I deferred, and then again, until at last I had to say yes. It’s so rare to be asked my usual response is, “Of course!”, no matter what. But entering the gallery seemed a step which couldn’t be taken back. You have a hundred conversations but one conversation marks you, and all the rest issue from that wound, or are shadowed by it. My entire engagement with the movies has been in theatrical settings where time can be granted material status, shrunk or swollen, folded or stacked. Now there was space to contend with and a viewer granted mobility, creating montages I could never imagine simply by moving, this was really wonderful. To arrive in your own time, to see in your own way, these are new kinds of happinesses.

Bob Black: Watching your movies in a gallery makes them feel more physically personal, almost like embracing someone, this doesn’t happen in a theatre. And then there is the question of mobility. In the middle of The Invisible Man I left and returned and my body was still settling and readjusting.

Marina: I know your films have been part of many international festivals, I was wondering: how often do you travel?

Mike: I’ve finished three feature length videos in the past three years so I’ve been busy accompanying them abroad, it seems the next airplane is never far. If only it were true what Virilio writes, that we arrive before we leave. On the other hand, what is familiar is the need for displacement, this phantom body, the sense that everyone is passing. On an airplane you wave good-bye to yourself.

Marina: Do you have that sense of belonging somewhere?

Bob: Yes, when you think about yourself as a filmmaker, do you think of yourself dealing with Canadian cinema?

Marina: Or Canadian art in general?

Mike: Canadian cinema and the fringe are both part of a minor literature to which I’m attached. Canada is a special case in relation to the American empire because of our proximity. Like most Canadians, I grew up on a steady diet of American television, movies and magazines. How to find my own pictures in the midst of this deluge? My work, like the work of so many others, is a way to talk back, to re-present, to restage some of these pictures, to change the unbearable into something like pleasure.

Marina: “You’ve seen everything so you stop looking…” Have you ever thought about not making films?

Mike: [laughing] Yes, but I was very depressed then…

Bob: You mean you were depressed about not making films?

Mike: How to clear enough space in order to see a picture? One of the problems in today’s globalization of pictures is that too many pictures arrive from too few places. And the pictures which arrive become invisible through their visibility.

Bob: Prior to his Tate show, Robert Frank also publicly lamented this crushing wave of pictures. Can you show anything anymore? This deluge of images produces blindness! Though your work summons this deluge and survives it. You have an obligation to expression, to make this offering, even if it’s only for a few people. I can still look at my son’s face and feel something.

Marina: Do you show your films to anyone before screening them publicly? Who are the first ones to see?

Mike: Yes, I test drive with friends before delivery. I think that in every making there are two objects at play, the manifest work you’re concerned with, and the sum of all the blind spots, the moments you can’t afford to look at. In order to produce a work you require focus and framing, you need to leave almost everything out, the way you bring this frame towards the world produces the attention of your art. But what that lies outside the frame also has a shape, and this is what the feedbackers can point out.

Marina: You collaborate with others when making films: actors, voices, and editors. How much control do you retain?

Mike: The Invisible Man was edited by Dennis Day and carries his hand in it. He’s a terrific editor. The shots hold a very specific weight, and are much longer than in my previous work. Dennis works so clean new risks were allowed.

Bob: What intrigued me compositionally about your work were the choices of excerpted scenes. Why a television commercial, a moment from Godard or a Hollywood film? Do you think about your shot in the context of the original movie or is it something purely visual you derive?

Mike: I’m being led and leading, there’s invariably an itch outside, a curiosity or necessity, which moves me to respond. The way the light falls on her face, the way he walks past a window. These pictures help me remember what it’s like to live inside a body.

Marina: I remember one moment in Imitations of Life when you’re telling a story about a game you played with your sister as children, imagining yourselves as rays of light …

Mike: Yes, in The Game (editor’s note: from Imitations of Life)…

Marina: You would make things visible by looking at them, and your mother grew concerned that whatever you imagined might, in fact, happen to you in your real life. While watching The Invisible Man I remember beautiful imagery of bodies standing on the ashen snow field, these strange, scattered bodies which looked beautiful and surreal and also “familiar.” Do you make a separation between you and your pictured life, fiction and documentary?

Mike: I forget both in the same way, so they’re equally influential. But when it comes time to show an emotion, to produce a picture of a moment, sometimes the picture arrives too quickly. I’m sure you’ve experienced it yourself, after the death of a friend, or someone close has miscarried, after only a few short hours you’re called to do something. You have to make dinner, you have to walk through the door and pretend you’re still human. If I were a documentary filmmaker, producing pictures of you 24 hours a day, I could review this footage of you performing yourself, walking through the door, making dinner… but I don’t think these pictures would show me what is happening. In order to arrive at documentary, the reality of this moment, sometimes fiction is required. Sometimes fiction is documentary. And all too often documentary is fiction, as our network newscasts show daily.

Bob: I buried my mother’s husband a couple of weeks ago. We went to the funeral and then we had to make turkey and pour someone a drink. Marina and I experienced the same thing after seeing your movies, now we have to construct some interview. This duality is always around us.

Can you talk about artists who have meant something to you. You mentioned Godard when you walked in this evening…

Mike: Godard is the beginning and the end.

Bob: He is our hero too. Let’s say Godard is the most well known of our heroes. [laughing] What other filmmakers, photographers or writers have been heroes to you Mike?

Mike: The books of Marguerite Duras have proved an enduring companion, she seems a genre unto herself, inexhaustibly precise. In the land of video, the work of Steve Reinke has been vitally important, he is fearless in his making, I’m not sure why. It’s as if the normal concerns that occupy artists (Will anyone like this? Do I have anything to say? Is this too much or too little?) never occurs to him. Steve talks in his work, and arriving from a stern, optical avant garde which mistrusted language, this came as a great relief. He granted permission to speak.

Marina: Well, you talk a lot in your movies [laughing]

Mike: Yeah, right. [laughing]

Bob: Who else? What about Godard versus Tarkovsky?

MH: It’s good that there is a room for both…

Bob: Thank God. [laughing] When people think of Godard they imagine his films, few have seen his video work. What about him has been meaningful to you?

Mike: Montage, mon beau souci. “If to direct is a glance, to edit is a beating of the heart. To anticipate is the characteristic of both. But what one seeks to foresee in space, the other seeks in time.” And especially this: ”its charm will consist in disclosing the unforeseen by an operation analogous to that in mathematics which makes an unknown entity evident.”

Godard produces montage through stories which are lived before they are filmed. Montage is at the heart of his practice, most recently schematized in the myth of stereo narrated in JLG/JLG. Germany produces Israel, Israel in turn produces Palestine. In this sequence, which consists of a single home movie shot showing a crude drawing, Godard conjures the hidden connections of state power, and between the most bitter of oppositions he generates not an affinity exactly, but a necessary link, a third term. This generation is a question of ethics and relationships, it opposes the traditions of emotional choreography, the way movies (or a state) are places where one is told what to feel and in what order. His pictures are forever thinking, refusing to land in a place, already ‘between’ the screen and its viewer. Of course the toll his pictures exact is very dear, there is a solitude that lends a crispness to his pictures, the room is clear, we can see into them with great clarity, but at what cost?

Bob: Film is composed, like memory, through opposition. But Godard shifts this too: whatever third term is produced as a result is also called into question. I wondered about that in your relationship to him. Your films, for me, have infected their originals. You don’t only borrow pictures but give them new meanings. From Contempt you take this beautiful image of the cinematographer sweeping his camera toward the audience, but now this iconic image is subverted or reinterpreted in your film. You’ve added a new life to Godard’s image, which began as an image of subversion to begin with… it’s hard to reinterpret Godard but you do… and he is busy doing the same thing.

Godard was always willing to show the sloppiness of structure, because this is an intellectual idea, but now there’s a sloppiness of emotion, in the humane sense. And your work has that same quality. In other words, your work is intellectually rigorous and yet unafraid to express very sloppy sentiment, sloppy in the human way. How do you admit emotions which might threaten the structures they inhabit?

Mike: I’m sometimes ready to keen over the edge in the grip of sentimentality, a feeling reined in via editing. Editing is a planned déjà vu. When you make the second or second hundred look at the same small arena of pictures this can become confusing. (For instance: one look can attach itself to the next to produce a trajectory of looking, now where has the subject gone? Lost in all this looking) The trick, if you can call it that, is not to let the feeling dry out over the endless repeat of images in post-production. Not to fall into the old divides of thinking and feeling.

Bob: You say an interesting thing in Imitations of Life about “our bodies becoming increasingly transparent.” How do you see the development of pictures? Will we still sit in front of TV?

Mike: You mean how will images be seen in the future? [Laughing] I think displays will be 3D, the sound will come from every direction and the experience will be interactive. Not bigger than life but better. And it should be freed from the screen, appearing all around its audience, like company. My picture, my friend, my lover. The worse things get, the more pictures will be pressed into service to cover the gap.

Marina: It will become like a game rather than film?

Mike: Perhaps the game is about living? Pictures may help us to perform a new version of family. It’s difficult to imagine a future in which pictures aren’t central to the relationships we have with one another. How do I look? How do I look at you? Speak to you? Touch?

Bob: Could you live without watching another movie?

Mike: (laughing)… No.

Bob: Let’s say you lose your eyesight.

Mike: Movies offer a place for dreams to rest and to begin again. They offer the possibility of different kinds of lives and relationships, this I would miss very much. It would be very lonely to live without movies, even though movies make you lonely too. [laughing]

Bob: A less philosophical question: how do you find Toronto, not as a place, as a city, but let’s say as an environment to see films, to have conversations with other filmmakers and artists?

Mike: This city was made for cinema. It is built up over ravines and watersheds, a cold place brokered into solitary dwellings. Let’s work all the time. Not “Hi, how are you?” but “How are you DOING?” These labyrinthian interiors are picture perfect for the movies. No coincidence that Toronto hosts more film festivals per year than anywhere in the world.

Bob: What about the reception of films? You can see a lot of films, there is a supportive group of filmmakers, but is this a place to talk about films?

Mike: Everyone is busy working here, and this multi-tasking velocity cuts against the reflection which makes speaking worthwhile. Maybe it’s just me. What I’m left with post festival is the mirage of witness. Even masterpieces dull when they arrive in such profusion.

Bob: Our bodies tell the story of our families, we are part of something, but we are also separate. Always alone. Your work is specific to this place but also universal, and your voice recites the story of this separation and communion. It opens and closes.