Public Lighting: an interview by Dominika Hadrova (Sept. 2004)

Dominka: Can you tell me how the movie began?

Mike: When I was eight years old I met my best friend. He was born on the same afternoon, in the same city and every thought he had also occured to me. Everything I wanted, he wanted. This lasted until we hit adolescence and he began to say no, to me, his friends, everything. Rules didn’t stick to Stan. He would spend a day up in a tree admiring the view, talked openly about drugs and sex, so I wasn’t entirely surprised when he arrived at school naked. What are we trying to hide behind these clothes? It was a rebuke against designer lifestyles already taking hold. Of course he was institutionalized after that, though there was nothing really wrong about him except for a mind which refused to close.

He told me later about a test which was administered each day. He was presented with a small stack of photographs, each showing a face in close-up, and asked who he would like to sit with on a bus. Who least? Unknown to him, each showed a man in the grip of severe psychosis (the manic depressive, the split personality) the test was premised on the condition that he would surely choose the person whose condition reflected his own. There was one normal in the bunch, and when he chose that face, his treatment would be over. Public Lighting begins with this rendering of types, reflecting on the ways we reproduce ourselves, our technologies of selfhood, the armatures of poses and pictures and writings that constitute our public selves.

Writing is the first of its seven parts, a combination of city film (in a much more modest fashion, but in the line of Berlin: Symphony of a City or Francis Thompson’s NY NY ) and portrait. The city is Amsterdam, though its iconic tourist destinations are largely ignored, Central Station is shown only from its backside, glimpsed from the ferry which connects North Amsterdam to the centre. The Artis Zoo, the failed utopian housing of the Behlmir, the Amstel River, the Albert Cuyp market, anti-war demonstrations and various street scenes are featured. Dutch writer Esma Moukhtar walks, suns and makes her bed through it all, writing as it occurs to her. The city is conjured from her writing, and having made her way through the population she decides there are only six different kinds of personality, and that she will write about each. She names this project “Public lighting,” (doppelganger of the movie), which proposes to take up the act of presentation, the persona, the way we appear to others (who light us up). While the six types of personality are never named they can easily be guessed at by the nature of the portraits which follow: the man falling out of love in restaurants is the depressive, Philip Glass is the obsessive, Madonna the narcissist, the woman in Tradition the amnesiac, the photographer in Hiro unable to awake from the nightmare of history, while Amy is the schizophrenic.

In the City is the second section and shows twenty six restaurants, alphabetically arranged, from Anywhere Lounge to Zelda’s. (Anywhere Lounge, Bagel Cafe, Cassis, Diablo, El Asador, Flip, Toss and Shake, Gabby’s, Happy Seven, Insomnia, JJ Muggs, KFC, Las Iguanas, Mr. Greek, Nataraj, Omonia, Paradise, Q Club, Richards, Scratch Daniels, Thai Bangkok, Utopia, Vitty’s, Wilde Oscars, XXX Diner, Zelda’s). Like Writing and Glass it is both a city film and a portrait, this time presenting the city of Toronto as a series of restaurant facades.

It opens in the country, in an emptied house (this motif of the empty house recurs in Tradition and in a more extended montage in Amy ), where we finally see a young boy getting out of bed, unable to sleep, caught up in dreams of escape. When he looks out the window he sees a train (every train in cinema is already the train of the Lumiéres, the beginnings of reproduction, the fall into spectacle and commerce) which delivers him to the city. There he begins a series of romantic misadventures with a number of men. Endings (sometimes the beginning as well) invariably occur in restaurants.

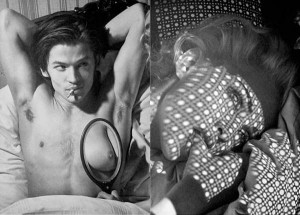

Shot in black and white super-8, the image appears often in superimposition. Restaurant facades alternate with shots of the narrator (shaving, walking, eating, cruising) and close-up shots of young women transported in ecstasy (from the classic NFB documentary about Paul Anka, Lonely Boy), their faces showing a wrenching transcendent devotion (immolated in the presence of their beloved, they are examplars of the birth of the modern teenager, a release of cold war tensions into adolescent pop hysteria). These faces contrast the dryly ironic tone of the voice-over, delivered by Canadian video artist Steve Reinke. This tape would be the blues if not for his even-tempered, mellifluous tones, which grants to the direst tragedy the consolation of a sonorous voice.

The closing image loops, suggesting that there is something cyclical in this man’s approach to love. That he is drawn only to the temporary and fleeting, to a gorging of appetite which must be fed again and again. It will not be enough to have the same dinner, the same lover, night after night, instead a restless searching provokes him across the alphabet, but while the scenes shift the result stays the same, he is caught in the circle of his own desire, looking for another who will say no.

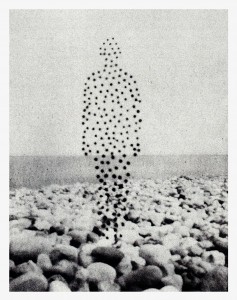

Glass is a portrait (though its subject appears only at the end) of New York composer Philip Glass. It is produced in movements which image different moments of the city (the Brooklyn Bridge, the subway, Central Park, Coney Island Beach) while a typewriter text scrolls across the cityscape. It opens with a series of archival black and white shots, mostly photographs made in the early part of the twentieth century, showing the living and working conditions of some of the poorest people in the city (invariably immigrants). Here are Glass’s (imagined) beginnings, his parent’s arrival via Ellis Island, the trials of the newly arrived, accompanied by a chorus of counting voices (of generations calling the tune).

This city portrait is an alternating current between historical New York and the present day, black and white and colour, often using footage from the same site or vantage years apart to display differences. The restless changes in Manhattan are contrasted with Glass’s music which, while rhythmic and driving, is contained within a small register of phrasings, many different pieces (solo or ensemble, orchestral or chamber) sound like variations of one another, even though they have been produced over decades. Glass replays the same melody over and again even as the city demonstrates its changes, offering micro/macro contrasts of figure and ground though the movie suggests that they are pitched to the same end. Glass’s music contains within its few notes a longing for eternity and the infinite, which the city embodies in its ever shifting appearance.

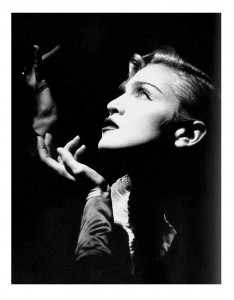

Hey Madonna takes the form of a letter (which is never a correspondence) to the pop star from a former lover. The rock vid promos for Vogue (abbreviated) and Oh Father (re-cut) play while a new text scrolls across the familiar pictures. It is a letter familiar to anyone who has become HIV positive, urged to contact all former sexual contacts and inform them (and for once, he writes, he is glad there aren’t so many). Madonna isn’t positive, but the images are rewritten and recut to emphasize the body’s mortality. In the opening sequence Madonna muses about the death of a good friend (she prepares herself for the shock by imagining him already dead), and while she glams her way through Vogue the text’s emphasis on dying recasts her supporting cast (young black dancers, most of them gay) as a backdrop of death (how many will die of AIDS?), most emphatically in the sequence which shows one dancer breaking moves while the camera fades out over and over, intimating his end.

In the middle segue sequence, while the opening chords of Vogue are refrained, Madonna appears in a bevy of posed photo-ops, including a visit to her parent’s grave (while she croons “Strike a pose”) cruelly juxtaposing the experience of grief with camera ready postures. Death as a pose, as a transmitted response (each culture has its own rites which govern passage over the border), Madonna is shown here as an exemplar of mourning. You’ve shown me how to live, now show me to die: Express yourself. How to stop looking for signs of decay in the body (the middle sequence shows a scene between Madonna and her doctor), which is only always growing older, closer to the end, inevitably giving way under the weight of the years, having to perform the circulations and repairs that allow us to endure. “It’s hard to watch you growing older” the letter writer inscribes, not because she looks any less perfect, but because it’s a reminder of what’s happening to us all who lack the multiplication of pictures, of selves, that haunt and elevate any celebrity.

Tradition is a brief which narrates a family compact of forgetting. Unknown to her, the lead character repeats everything her mother did, all her friends are mirrors of her mother’s friends, her decisions, her hopes, and most of all her forgetting. Her mother could never remember a thing, and neither can she. This is the tradition of the film’s title, not the generational gift of past wisdoms and oppressions, but a genetic disposition, a body memory of no memory at all.

Memories of China come to her in glimpses and fragments or superimposed waves of pictures (Is she living there? Or in a western city where her accent clearly places her). This is one homecoming movie which never finally arrives, denied even the wound of loss, and in its place a stunned diasporic response (the old Canadian cry of national identity is also her own: where is here?). “I take pictures not to help me remember but to record my forgetting.”

“Mother says one day you’ll have a daughter. Mother says that like me she used to forget everything. Forgetting is a tradition in my family.” The devouring past, still hungry, waits to be fulfilled. Not character as destiny, but bloodlines, ancient curses, the travel between old world and new reversed here, caught between borders in a stateless wandering. Neither here nor there.

Hiro was the only subset of Public Lighting I cut myself. I was granted a residence at the Western Front in Vancouver which meant a room with a view and an edit suite down the hall. Hiro was shot and cut in a month of all day/night sessions. It shows a Japanese photographer haunted by memories of Hiroshima, an ambulance chaser and thrill seeker, drawn especially to fires (like moths, like the fires which consumed blocks after the blast). His compulsion a reflex of memory, his photography a phantom limb. Because I cut it hands-on there is a lot of fine detailing in the montage which proceeds like a series of snapshots with black-outs punctuating dream fragments and daytime encounters. A parallel ghost narrative is introduced at the beginning, a shadowy, staggered man climbs down a stairwell, and over the course of the movie we see him cross a bridge, jump off a roof, limp across the waterfront until he is finally encountered by the photographer (whose name is Hiro, played by actor Hiro Kanagawa). The man has collapsed, and lies unmoving in an east side alley. Hiro’s camera shield is finally put away as he decides should I shoot him or? He calls an ambulance, unable to take a picture of his dead dreamed double. The siren is heard over black (“after” the end), completing the transference.

Dominka: What about the last section of Public Lighting, called Amy?

Mike: There are two fathers in Amy, the first produces the home movie footage that opens the film, the second is Jock Sturges. Both produce pictures (as the paternal relation is largely fictional (unlike the maternal relation which is embodied) picture taking is a way to reclaim the authority of origins. This is my chair, this is my house, this is my daughter. These two fathers exist in a line of picture takers which produce a way of looking, a way of being looked at. Amy opens with a home movie sequence whose source is identified in the first shot which shows the father loading up his super-8 projector. Looking is already looking again, re-viewing (there is no first look, only a circulation).

The next shot shows a teenage girl walking out of her house while the camera follows her. She is awkward and shy, the camera look is too much, it causes shame and embarrassment (Not because she is never looked at, and so is unused to it, but because she already looks at herself all the time, the camera’s presence is an unwelcome reminder. She has learned her lesson well.) The daughter’s response contrasts with her brother who is amused and stoic, much more rigid than his sister (we all have our parts to play), but clearly unafraid, able to look back, to answer the camera’s look. The look divides genders.

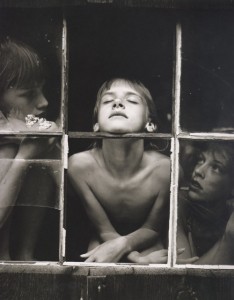

There are two sequences in the film which show girl gatherings, and both are initiations. In the first a posse of girls are led to the top floor of a house where milk and flour is heaped on them in a gesture of ritual abuse. They are blindfolded, seen but not seeing, and their tormentors are also girls. Once they have endured this bit of play, one of them is raised from a kneeling position, her blindfold removed, and a demure kiss signals acceptance into the sorority. Like the photographs of Amy, they undergo a rite of initiation, this time at the hands of other girls. Once again looking and power are related.

In the movie’s closing shot there is a race run exclusively by pre-teen girls. They run towards the source of the image, the place that is looking at them, the vantage point. Far from resisting this look they have no choice but to embrace it, to desire it, to find in it the basis for their own self regard. Once again this massing occurs in a climate of competition and exertion. The race is another form of initation into an all-girl social order, a measurement and indicator of character and status. (The beautiful one, the fast one, the smart one.) Both groups show that ‘the look’ is not an exclusive male preserve, that once the look is digested and internalized, it is very effectively disseminated (like a virus) by women, even though it is women who suffer under this regime of looking.

After Amy‘s opening home movies there are a number of shots of an empty house (a second home movie without residents). A lurking presence insinuates itself, a menace implied by small movements of the camera, and tiny movements inside the frame, finger marks left on a window. This is the stage for the look, the place where the trauma occurs, is reinforced and becomes part of personality. These dark, cramped interiors finally release in an escape through grass and light and finally a bicycle races away. Though escape from an internalized condition (the way we look at ourselves) is only temporary.

There are three photographs of Amy which form the basis for the movie, each is a reflection on looking, and they are presented in reverse chronology, the earliest picture appears last. All are taken on the beach, and in each Amy answers the look of the camera, more than aware she is being photographed. The pictures were made by American photographer Jock Sturges who has pursued a practice over the past decades of documenting the transition from girl to woman, producing scores of idealized nudes in natural settings with a large format camera. What is missing in these pictures is the apparatus itself (only a high production sheen remains as evidence) and the reflection of its subject (what is she thinking? what is she thinking now when she looks back on these pictures?)

These three photographs, like any other, are a record of a time, a moment’s impression, but apart from their status as memento and place holder, they are also the event itself. They are the initiation from girl to woman that they seek to document, it is through the camera that this transformation occurs, the camera is agent and document of its agency. Amy acknowledges the look of the camera not from a position of equality (“face to face”) but as an admission (“Now I will look at myself the way you look at me.”) The camera’s fragmenting gaze delivers her to herself as an amalgam of parts (she speaks of her breasts, the marks on her legs, her face, and then refers to herself in the third person, as if she were an object, a thing).

In her opening voice-over Amy says, “Last night I was watching television when this terrible thing happened. All the talk show hosts, all the guest stars, even the news anchors, all started talking like me, and looking like me…” Amy finds herself, her look, the way she looks at herself, reflected everywhere. She is caught in a circulation of looks (the home movie, but also television, the systems of reproduction work to reproduce her look).

In her second voice-over Amy says about her photographer, “No one really wears any clothes out here, not on the beach, that would be weird, right? Only he’s got all this stuff on him, the big camera and meters and boards so he’s not really naked, not at all.” Both figures are naked, but only one is seen, and it is in the act of being looked at that one becomes naked. She is newly sexualized, looked at with desire, with the budding desire that separates girl from women, as an object of men’s attention, an attention signalled in the photographs. Even if she held the camera, and made pictures, she would continue to reproduce the look. She will always be naked because her look attaches itself to a (male) history of looking.

A series of home movies follow her second photograph, we see Amy being brought as a child from the hospital, then sitting on her parent’s knees, shyly smiling into the super-8 camera. We also see Amy later in life, holding her own camera in a park, in a series of blurred, frozen frames which turn her into a shock of light and dark. The photographs of her initiation are crisp and clear, while the present is a haze of abstractions, always in movement, as if trying to escape, or trying to find a footing, a place from which she can begin her own reproduction.

Later Amy says, “The only person that’s really looked at us like this is mom and dad, only he isn’t blood, no, not at all. And that makes all the difference.” Parents see their children naked, care for them, tend to them, school them. But Jock is part of a line of metaphorical parents (or teachers) who will grant new meanings to innocent activities, now being naked on the beach will hold different associations, no longer only a family frolic of nudists, but part of a sexualized series of encounters with the look she will carry with her the rest of her life.

Amy is usually heard in voice-over, and its source is shown periodically in images of Amy in a recording booth where headphones and microphone are very visible. She often directly addresses the camera. Unlike the photographs, the means of reproduction are made manifest (Godard: “I want to show, and to show my showing.”) In her closing image she says, “I’m starting to look at myself the way you’re looking at me now.” Here she implicates the audience’s look, she is being served up again for an anonymous audience, and she states that this look is also part of the look of her once photographer, that the cinema audience is also busy fragmenting the body, sexualizing the female, objectifying, and that this look is being absorbed and digested by its receiver. In the movie’s closing image a group of high school girls sing the old Beach Boys number God Only Knows (“God only knows what I’d do without you…”) referring to a world without the male gaze to determine response. What would it be like to grow up without them? We may never know.

Animals That Make Pictures: an interview about Public Lighting by Tomás Tetiva and Petra Veselá (October 2004)

Tomás Tetiva: How did you like Kiarostami’s Five which we watched yesterday? You probably know this kind of movie via Andy Warhol’s work in the sixties, but was it a real movie, joke movie or cult movie? I’m still not sure that I like these long, slow shots, wasn’t it finally too static?

Mike: I’m still digesting. Five arrives from minimal art, trying to clean the room of our attentions, to take away the noise of dramatic expectation and even character, so that we might notice some small moment. To notice a small moment can sometimes be a great victory. What’s so risky about Kiarostami’s film is that he asks so much from his viewers, his movie is radically incomplete, he sends his child out into the world without arms, and only half a face. The simplest thing to do as an audience is refuse. No, sorry, this won’t do at all. This is no movie, and no child. As an artist he wants to meet us half-way, he doesn’t want to fill the screen, but to present instead a place where an image and spectator might meet. Many will take this as provocation. He offers a small picture, a little bit of sound, and then he asks us to fill in the rest. This is a great risk, and as we saw by the response of the many who walked out, it doesn’t work for those who retain the expectations of theatre.

For myself I felt the pernicious accompaniment of small questions, moments of yesterday and the day before, the small anxieties which take the place of thought. I am watching them rise up because the movie isn’t “taking me away.” Instead, the movie allows a place where I can see the noise I create, and understand that it is exactly to escape this noise (which at other times I like to call myself) that I go to the movies. There is a word we use for this experience: boredom.

I felt the two opening shots (of five) in Kiarostami’s Five were unnecessary, but that the last couple were terrific. Once again in the judge’s chair, hiding behind “I like” and “I want.” The final shot (nearly twenty minutes long) draws the audience (those who are left) into the movie in a very physical way. Both screen and theatre are black, and we are surrounded by the sound, as we would be “in life.” We are offered a chance to listen to the frogs singing to one another, and the birds alighting, and the rain storm which clears this chatter, and their return, and then daybreak. (It is also my long night, my day break, K offers me only five shots but there is already a journey, a wandering and homecoming, in a word, transcendence.) How much image or life do you need? How much life do we give up when we see a picture (and when do we stop seeing them?) Hard questions from a hard film.

Tomás: Do you like punk?

Mike: Once upon a time. Now I like spare music, I don’t need so many notes, I prefer to hear the same refrains for a long time, like William Basinski, or the Australian guitarist Oren Ambarchi or the German pop reworker Stephan Mathieu or the Canadian laptopper Tim Hecker. Punk used to provide a place for my anger, now I get angry without accompaniment.

Just before coming here to Jihlava I caught a suite of concerts from the Touch label in Amsterdam. The headliner was Christian Fennesz, whose Endless Summer (Mego, 2001) remains a breakthrough marriage of sweet melodics and glitch electronica. But the night we saw him he was completely out of sorts. He always chose the wrong loop, he picked up the guitar which caused great anticipation (so many of these folks sit numbly by their Apples) but his playing was pedestrian, leading nowhere in particular. But even so there were strains and hints of that sweet sound he is so fine at producing. What he was expressing, in a deeply personal way, was a direct transmission of his feeling as he stood there before us. It wasn’t a perfect day and he wasn’t going to dress it up for the concert. Heaven doesn’t happen on the clock, it occurs sometimes, in between moments, maybe when you’re least expecting it. And so these sweet sounds remained as distant memory, a ghost image, haunting the present, the place between us. The concert was a brilliant demonstration of failure. Live in every sense.

Tomás: You use many pictures in your movies. How do you choose pictures from the archives–is it rationale choice or intuition?

Mike: I think it’s a question of attention. You draw your attention to one part of the image world, or one aspect of the world around you, and events begin to gather around that point. This point could have something to do with sexuality, for instance, and lead you to meeting people who are searching with their bodies. It could provoke coincidences, like when Kenneth Anger was editing his biker movie Scorpio Rising. There was a knock on the door and when he opened it a delivery man was waiting with a package. He signed for it, though it was clearly at the wrong place, and found that he had been given a life of Christ, which he promptly and very usefully deployed in his own film. This is how the harnessing of attention works. Is this rational or intuitive? I think it’s a question of necessity. What is required for the artist is to take the next step.

The first three chapters of Public Lighting feature portraits of cities and individuals at the same time. Each of these cities were gathered in different ways. In the portrait of composer Philip Glass called Glass, I divided the movie up into five movements, each of which was fixed in a Manhattan location (Central Park, Brooklyn Bridge, subway). The movie begins with photographs, frozen moments, and then jumps into motion. It begins with immigrant life in a series of tenement freezes, and slowly moves out (a radial movement) but also upwards (the city builds and grows).

Tomás: What about the scenes of Madonna in Hey Madonna ? Has she seen the movie? Why did you put it there?

Mike: I don’t think she’s seen it, though it played yesterday in London. While I’m hardly in a position to ask for her pictures, I feel that they surround me, I don’t need to find them, when I look out they are already there, looking back at me. They’re already my pictures, part of how I imagine the world (like the tree which grows in front of my building, the newspaper boxes perched on the corner). But as someone who sees pictures, I feel this seeing arrives with some responsibility, not simply to digest, but to pose a question. Why these pictures? How do they work? How are they working on me? How else might they work? The globalization of pictures insists that images and sounds arrive in a one-way flow, they come from the place which has money and fills in the holes between a word and its meaning, or a sound and its feeling. Sometimes it’s nice to reverse the flow and talk back.

I resettle these well known pictures, writing over them in an act of audio-visual graffiti, shortening, tightening, setting them into different relations, especially connected to AIDS and death. Her dancers are all young and gay (well, maybe one isn’t gay) and the threat of AIDS for them is very real. After seeing a very personal text scroll about AIDS, when we encounter the brief montage of a young dancer who appears in a series of quick fade-outs, I think it’s difficult not to read this as a premonition of his death, that he is making his last stand here. The mainstream, in other words the globalized entertainment industry, has plucked a moment from a fringe subculture (in this instance voguing) and turned it to its own ends. I’m following a similar momentum, extending this gesture, turning this turn, but towards a very different end. I’m not trying to replace the future with commodity fetishes. I’m offering a place to think about pictures, a new frame in which these pictures can be seen.

Tomás: What do you think about poetry? I see poetry in your movies. Do you like this principle and why did you choose to making movies, not writing?

Mike: My heart (a fist wrapped in blood says Closer ) remains with the Canadian poet Anne Carson. Unlike my relation to movies where I see many different things, I am content to read Carson over and again. There is a line from Beauty of the Husband which continues to haunt me, and appears in the prelude of Public Lighting: “Every wound gives off its own light.” Isn’t this cinema? Isn’t each movie a silver wound issuing pictures, and don’t we arrive at the theatre hoping for a glimpse inside this body?

Tomás: I can see lyrics in your movies which are like poetry.

Mike: The impulse might be the same. Not the story which occasions a feeling, but the story of the feeling. If exposition were set in traditional story frames, characters would be required, the necessity of the next because. Resolutions would be adopted, conclusions arrived at. In poetry one is allowed the documentary luxury of exploring a moment, and releasing it from the burden of connection with every other moment. Jean Perret was telling me yesterday about two kinds of memory, the souvenir and the mémoire. The souvenir is the past as it appears in stories, the past which is already a story. The mémoire emerges in places like psychoanalysis, or the cinema, a convulsive, eruptive memory which appears as a fragment, a raw bundle. Jean insists that documentary cinema keep a place for these mémoires, that the task of a movie isn’t simply to bundle its audience through to the end, but to stake these fragments out and let them stand there, as raw and undigested fragments if necessary. These unstoried moments might be akin to the poetry you’re after.

Petra Veselá: Is it what you are looking for in your movies, to reveal these fragments?

Mike: Not just a perfect movie, but a perfect audience. I offer a view on pictures, but try to conjure a place where the audience can make own associations. My movies resist absolute closure, hopefully allowing you to dream your own pictures. The aim is not to have my pictures obliterate yours, but to allow both to move together, in a duet. To grant a place for this mystery, for the large place that is you sitting beside me, and you and you. To grant a place so this mystery can circulate, not in order to reveal itself and be known (my movies aren’t detective stories, let’s get to the bottom of this) but to co-exist in our independent singularities.

In a traditional movie they talk about suspending disbelief, forgetting yourself, leaving your concerns behind. This is contrary to the cinema I’m interested in, or the life I’m interested in. The cinema is also life, not an escape from it. Sometimes the pictures I make are a little too full, there’s too much to see, and I fully expect people will wander off into their own thoughts, or move alongside (watching themselves watching), not always “following” the picture. For a movie to work, it’s not necessary to be forever following.

Tomás: Do you write a screenplay before shooting?

Mike: Public Lighting ‘s opening movement is a portrait of my friend Esma who lives in Amsterdam. We explored the city together, hanging out and sharing our lives. This is how the movie developed, a day at a time, a sentence at a time. Amsterdam is a show city, built for tourists, but there are many areas where visitors never arrive, places she hadn’t been for a while. We managed to retrace her loops and familiars (inevitable isn’t it?) but also to extend them. Each day I made notes of where we’d been and what was shot (very little in each place, often no more than a brief shot, a minute or less), and I forayed out on my own and made some suggestions, though mostly it was a question of being led. I was the visitor in this movie. In the movie (this chapter is calling “Writing”) she speaks as a writer, which she is, and as someone particularly interested in formal qualities (the shape of language, or in the words of the movie “the six types of personality:” people as shapes.) I tried to shoot through glass and plastic and through light, trying to find these shapes, this body and embodiment. This city portrait is always inhabited, always being framed by the body which encounters it, whether with a camera or not.

A note about the six different kinds of personality. There are a limited number of elements in the world, yet taken in combination they produce a fantastic variety of substances. What I want to offer is a construction zone where these models are apprised, examined, pulled apart, stuffed with pictures then put back into the arena (the frame) for review. How do I look? How do I look at what I am looking at? And in the cinema there is also this question: how do we look? How do we say “we”? At what point exactly does the image on the screen, the life up there on the screen, in the dark, become our life? Us, together.

Is it really possible to say the words, “I love you” for the first time. How many people have said them before? Are they my words or yours? Or our words? At the moment of my most intense singularity, when I am expressing myself, my own desire most fully, I am also saying We. I love you. We love you. I think we are complicated animals. Animals that make pictures.

Tomás: Political issues?

Mike: It’s a deep concern of course, exaggerated through traveling. To see certain moments of American culture repeated wherever I go is distressing. Everywhere the cinema is occupied, so the Czech cinema is a minority in the Czech Republic, the Canadian cinema is a minority in Canada. As Jean Perret said in the closing ceremony, this festival in Jihlava represents a resistance to corporate looking, it creates a different sense of time, a time of reflection perhaps. And inside this time a different kind of subject may be born.

Public Lighting shows the lives of individuals but not in any direct, expository fashion. To change how we say something means that what we say might also be changed. The mainstream offers us not only certain formalized structures of storytelling (ways to imagine our lives) but certain kinds of lives, again and again.

I’m still looking for way to struggle against the empire. A way to say no. My movies, this festival, are both small gestures, hardly able to effect enormous change. There are many questions I have about small. What is a small thing, and how are these small ideas transmitted? In our speaking today, for instance, can we produce pictures with our words that can take root alongside other people’s pictures? Isn’t this already a hope, not a utopian beginning, a perfect world, but a hope in the grimy, empire filled world of death that we are actually living in?

It’s not only about saying no. It’s also about falling in love. When we fall in love we say yes. I think this can also be a political act. Though not necessarily, it depends, falling in love can be like saying the word God, just the prelude for murder. But it can also mean something else: a rare and beautiful kindness, a new empathy, invented between two people (but why two? Does love come in pairs? Why not five or nine?)

Tragedy, Power and Possibility: Always on the chase for pictures of my own An interview by Jindriska Blahova (October 2004)

Ravishing swirls of pictures and memories. The personal memories and those that one never had. The past in an ecstatic clinch with the present, so firm that one cannot slip. And the apparition of the future everywhere. The future, which is inescapable in the same way as the gentle power of language, or the inevitability of making certain type of movies and not others, emerges from a translucent negative or the eyes in a photograph. In all these things the touch of Canadian documentary film maker and producer Mike Hoolboom is felt. Hoolboom visited for the second time the International Documentary Film Festival in Jihlava. The following interview, which moves in chapters over fragmentary parts of his latest movie Public Lighting , also seeks to find a “shape behind” this author. Not to present him as a “raw material,” as a collection of facts, but to see at least miniature fractions of the “ghostworld” and history behind Hoolboom’s personality.

Jindriska: Let’s start, like your picture, with the prologue. The young writer is talking about her first novel and outlines its inner structure. The novel is going to portray six different kinds of personalities. In this way she also reveals the structure of the movie. The prologue is overloaded with technical devices such as cameras, projectors, and glass prisms. All of them are instruments that in some way capture a subject and transform it into pictures. Later on, they also appear in other chapters. What does it mean for you to look, to observe?

Mike: Godard says that it’s important to show and to show me showing. Most pictures appear transparent, always already there. The means of their reproduction, the choices made in their construction, the way they have arrived, can be seen only in glimpses. The apparatus and its ideology of shaping are hidden together. In my work I feel it’s important to show the apparatus at work.

Jindriska: Your cinematic autobiography is very distinctive, full of visual intelligence and innovative filmic methods. But the fascinating visuality always co-exists with the inner message and therefore is never mere art for art, an intoxication with pictures. Nevertheless the unique picture work is the thing that strikes one first in encountering your films. If there is any inner sense in the picture, what would it be?

Mike: I live in the reality of pictures. My notions of what is beautiful, for example, arise from the picture world. But take, for example, the science fiction novel China Mountain Zhang, which describes a world where the American empire gives way to the Chinese, who dominate not only economics, but culture. The most perfect human being is Chinese, while white people in this new world order are considered secondary and inferior. The most perfect mouth, and hair, and manner of speaking, all belongs to the Chinese.

I live in Canada which neighbours a cruel cultural giant. Most of the population of my country lives within two hundred kilometers of the American border. We grew up on their television, movies and magazines, and of course this situation exists in many parts of the world, but in Canada it’s particularly acute. One of the ways in which the American empire functions is to proliferate pictures (pictures which are already ideas, entire life stories). In Canada, like everywhere else, there is a struggle to find our own pictures.

Jindriska: Pictures as a mean for struggle?

Mike: The power of images continues to be understated. Even when I’m talking with close friends there are pictures between us. Somehow we have to reach through these pictures to find one another. Though we are inevitably deflected, distorted and refracted through pictures which constitute ambition, the value of work, the shape of the future. All these things arrive through pictures.

Jindriska: What you just said corresponds with one sentence from the closing chapter of Public Lighting called Amy. She reads her confession in a recording booth and if I recollect her words correctly, she says: “The pictures never stop. The taking never ends.” It can be read as one of the elementary notions that underline this movie…

Mike: The words we use for making pictures are shooting and capturing, the terminology of the hunt. In the times of kings, people existed like subjects. Kings had their subjects, and subjects belonged to them. In place of kings today we have many different things including the cinema. The cinema is also a place you look up to. You gather together and you look up. The cinema has its subject which is the audience, just like the king. Cinema produces subjects. It is not just a picture of. We become pictures as we look at them. I think we understand ourselves, our bodies, by the choice of these pictures. The way these pictures choose us.

Jindriska: The theme of dominance recurs in Amy’s statement about her American photographer. She says, “He smells American.” I wonder, how does American smell?

Mike: I would say it is the strongest smell in the room. I’m very happy that Michael Moore makes movies, and especially that they’re so widely shown. But while they articulate some important political moments (the systematized poverty, government hand-outs (“contracts”) for defense industries, the collusion of the National Rifle Association (freedom of speech used as class warfare) all deployed as necessary backdrops to the high school shooting in Bowling for Columbine) they have large blind spots. He understands nothing about the world outside American borders. Nothing. When he tries, for instance, to deal with the Iraqi war in Fahrenheit 9-11, he can’t find a picture. He’s at a loss. But Moore has become the lingua franca of the documentary world, the same way that American fiction film has. I come from a small portion of the media microverse called fringe films which the Americans similarly dominate. They are the forefathers and foremothers, the ancestors, the inn is full, the ship has sailed, good-bye. Everything is already done before you arrive. He has that kind of smell. You can always sit down and have some dinner, the one that’s already cooked, but you can’t make it for yourself.

Jindriska: Another important topic in Public Lighting is how the subject is grasped or captured by their surroundings, violently changed by the environment and its visions and conception of the subject. The subject’s subjugation recurs again and again through the movie, for instance in the chapter called Tradition. The central character can’t remember anything, and lives in other people’s sentences, she is what other people say. Do you consider this process of finding, appropriating and sustaining identity a violent process?

Mike: Violent is not the word I would use. The Amy chapter begins with three photographs taken many years ago. They show Amy as a girl-woman, exactly at this in-between moment, no longer a girl anymore, not quite a woman. The photographs record this transition, and more than that, they are the transition. In these photographs Amy receives the look of her photographer, and comes to see herself the way he does. Every day she goes out to the beach, like everyone else, without her clothes, but in these pictures she is naked for the first time. She regards her body as a thing apart from her, a sexualized thing, glimpsed through male eyes, and then through her own. I don’t know if I would call that violent, though it’s certainly tragic. Maybe inescapable.

Jindriska: You yourself are the man of apparatus, the man of cinema, since you hold the camera you influence the way reality will appear. Amy describes the photographer on the beach who takes pictures of her as not-being-naked because he’s always holding/carrying a camera. Is the feeling of not-being-naked the reason why you personally use a camera?

Mike: I would like to imagine not, though I live like through my fears, clothed in my pictures of fear, like everyone else. You can do so many different things with the camera. You can use it as a shield, as a way to say no, to refuse the world. The camera can serve as a kind of punishment, a weapon used against its subjects. As for me, I’m not engaged in the so-called direct transmission of experience. Neither cinema verité or reality TV. I live alongside my subjects, talking with them, we discuss things and negotiate this delicate place of representation. What I’m showing is not simply the fact of their life but also the way in which these facts are converted into pictures. You can always feel my hand in it. Neither naked nor invisible.

Jindriska: Your movies mix personal themes with other people’s stories. How do you access their lives?

Mike: Everyone has their own stories to tell, and sometimes, more often than we imagine perhaps, we tell our own story by recounting the narratives of others. Stories come to me from being with people, talking not only about how we are going to make a movie, but also what we did yesterday. These meetings are already an insistence, perhaps not a script, but at least a hand pointing the way. I make films on a very low fidelity level in terms of means, high fidelity in terms of feelings and encounter. Things invariably come to me. As Jean Perret says, you have to provoke chance.

Jindriska: Pictures come to you like the words coming to the writer in the prologue…

Mike: Yes, I met Esma Moukhtar in Amsterdam whose background is in art and philosophy. She has a rigorous, almost formal way of viewing and encountering the world, granting attention to patterns of shaping, of how shapes interact, whether as thoughts or themes. Out of these shapes there are basic structures which can combine to produce all other shapes, like the periodic table of elements, for instance. But perhaps the same designs could be applied to personalities. This is the central conceit behind the structure of Public Lighting.

Jindriska: Which of the six chapters do you like most?

Mike: Today I like the Hiro chapter, because it narrates memory and amnesia. He is haunted by memories he is too young to have and I share this feeling.

Jindriska: The hero is haunted by the atomic histories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. What memories haunt you?

Mike: Hiro’s hero is a photographer haunted by the atomic flash in Japan, a flash which recurs whenever he takes a picture. Throughout the movie, parallel to his story, there is a recurrent, nighttime pursuit, a chance encounter, a rendevous, which he is moving towards despite himself. Unknowingly. Unconsciously you could say. This is the encounter at the end of the movie where he finds an unmoving man lying in an alleyway. Hiro is always too late with his camera (the image always arrives too late!), stumbling, distant, separated from events. He is haunted by events which he hasn’t experienced, and in this way we are the same. Firstly there is the experience of my parents during the second world war, very extreme experiences of hunger and incarceration, which was very different from my childhood. As the eldest child in this new country there was a double vision at work; there is the world that I experienced projected onto the ghost world of my parents. The early lesson was: pictures are not transparent. Things are not as they appear. Verité was impossible as a result, my movies had to show, or try to show, something else.

Jindriska: You show your subjects as a stream of memories. Past, present and future layers everywhere intertwine. One of your methods, especially in the first chapter, is the diffusion of public and private. How invasive do you consider this penetration of private into public and vice versa?

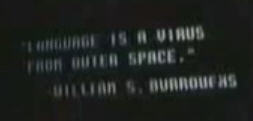

Mike: This year I underwent a very difficult treatment for hepatitis. The medication offers a variety of side effects including a shift in brain chemistry. I found myself having intense feelings and moods for days at a time. And these feelings seemed unrelated to events or causes, in a single moment overwhelming sadness might arise which could last for three days. My feelings would come and go like the weather and I began to wonder again who are we? Can I change just like that because I have a little chemical in my body? I thing we are very permeable. Our body is a hole and the world is coming in. As well, of course, we are spoken by language. I believe with Burroughs that language is viral.

Jindriska: Do you consider it a demand of identity? For instance the woman’s identity in Tradition is formed in a slightly scary way, she is caught in the prison house of language.

Mike: There is also something at once magical and tragic in this repetition of her mother’s life, the way her life receives her mother’s. It’s also possible to embrace this familial fate, and find in this small arena in which most of us live our lives, an occasion for happiness and celebration. It’s not only damage. Not necessarily.

Jindriska: In the Philip Glass chapter you say that his music asks you to touch eternity. What would you like your movies would ask?

Mike: I hope that my movies give the audience a few tools, something useful in order to be able to think more clearly about the pictures in their lives. About the pictures that are important to them. To be able to reflect on, without simply reflecting, the pictures that surround us.

Jindriska: When I return to the structure of your film, the fragments dominate. You are fond of chapters, pieces, single memories, photographs… In the Glass chapter you declare that he has achieved wholeness which you admire in a certain way. Since Glass is almost some kind of confession, are you an author in search of wholesness? And if yes, have you already found it?

Mike: My movies are still in parts, striving to be one thing. If Public Lighting would be a Philip Glass movie, it would not be in parts, it would have a serial form, looking at one tiny aspect from many different angles. Which is what we usually do most of the time. We play out infinite variations of our small theme. I can hear Philip Glass’s way and respect it, and sometimes long for it, but this is not my way.

Jindriska: But you still want to become the movie like he became the music?

Mike: Yes, absolutely.

Jindriska: Are you close?

Mike: No, just at the beginning.

JB: It can be disappointing.

Mike: No, I’m very happy.

Jindriska: In Glass you also say: “I know who I am by the choices I make.” What choices did Mike Hoolboom make recently that assure him of who he is?

Mike: The choice? I’m going back home to Toronto in about a week, but I have been here for five weeks already. The biggest choice I made recently, which ripped a hole in my life, was to come here, to say yes to more openness and fluidity. To step on the airplane, to go to a place which I don’t know, and to meet new people and find out more about them, how they live and what they want and how they want it. The task is to try to bring some of these understandings and beings home, to live in this other mind.

Jindriska: All the time you are hunting images…

Mike: Yes.