Panic Bodies: an interview with Mike Hoolboom by Larissa Fan

Larissa Fan: Like any body of work that endures over a number of years there is a noticeable evolution in your films: images and techniques recycled, narrative developments introduced, etc. Could you trace that evolution not in terms of films, but in terms of your reflection on film. (That is, did you set out to do what you’ve done, or did your interests deviate in the course of your career, and what are those interests now?)

Mike Hoolboom: Some begin with a map. They look out into the future and it is never a foreign country. Still others are born with a prodigal imagination. They are so intimate with their muse that they enter the world of reproduction with grace and certainty. Like Rimbaud, who by the ripe old age of twenty-one had finished with poetry, having already said all he needed to. This was never my way. I entered in confusion, proceeded in doubt, and in place of pictures managed to collect only a dense fog. Sustained by the joy I found in making, its required solitary a great consolation, I uncovered everywhere new confusions. Part of my problem was that I have a slut’s attention. Everything in the movies was attractive to me – musicals but also films made entirely of grain, flicker films and film noir. Serious filmers, mature artists, venture along a single path. They are auteurs, with a recognizable style and identifiable themes. My work looks like a group show.

At last I recalled a story my mother told me. She grew up in Indonesia, in a small village whose water supply was housed in a well in the main square. One morning she set off with Kees, a nasty belligerent who no one could stand but her father. When they arrived at the well the ground was muddy and he fell in, and for three days he was trapped there while villagers lowered food down to keep him from starving. He emerged a changed man. He had grown a kindness somehow, everyone remarked on it, shed the anger that had always accompanied him. What he had realized is that we’re all stuck in that well, forced to look out of the small hole of our personality. Surrounded by infinity.

LF: Do you watch traditional narrative films? If so, are there are any filmmakers that you feel have had an influence on your work?

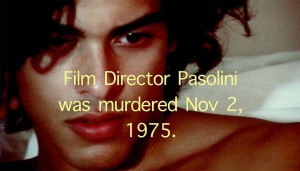

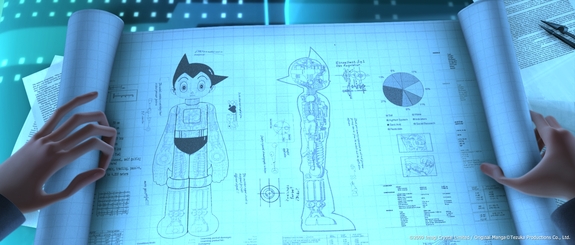

MH: When I learned to talk I learned through repeating. Breakfast. Father. Humiliation. It’s impossible to speak without quoting. Because all the words I use have been used before. And it’s the same with movies. I think that every picture ha already been made, and that movies are primarily an art of relationships, of placing one thing next to another. Truffaut said that the first film you make is a blueprint for future work, it’s a film you re-make over and over. But really it’s the first film you watch that is being re-made, re-seen through all the veils of the movies that come after. Perhaps after all it’s not important to see so many movies, maybe we could watch only one, understand the way it changes as we change, until at last we can see it as it really is, as the movie we make each day when we get up in the morning.

LF: I’m wondering about your working method. Do you tend to have a really clear idea of what you want when you start filming, or is it more of a gathering and sorting process?

MH: I wish I could say it was planned from the beginning but it’s not. I’ve always wanted to be a filmmaker like Hitchcock who I think is able to see his films before they’re made. I imagine him like the host of a great party who begins alone, in a theatre, and invite those close to him to share this view, this fascination, and slowly all the seats fill, as his friends invite others, until there are theatres round the world watching in delight. But I lack the imagination. And because I’m so poor technically, nothing ever comes out the way I imagine. Instead, something else appears. And this something else is what my films are about. Increasingly, I’m trying to get out of the way of this something else, trying not to let me ego stand in the way of the film that is trying to make itself heard. Which is why I’m always following my films, carried away to places they feel comfortable in. The light they need to be seen in.

LF: What is the genesis of Panic Bodies (70 minutes 1998)?

MH: It began with a line from Clive Barker: “We are all books blood, wherever they open us up, we are red.” It was up to me to take the next step. Imagine a cinema of blood. Or a blood of light. There are thirty million of us now spread across the globe who are HIV+. The years remaining to us will be written in our blood.

LF: Panic Bodies is a compilation of six short films, each featuring a different body or performance. How did the films come together?

MH: When the first couple were done I felt they needed company. It was like joining a rock band, okay, you’ve found a really kick ass drummer and the lead guitarist is doing things to your insides that are probably illegal but it still needs something, it lacks a grove, so you go out and find a bass player. Mostly I’ve made short films but as my waist widens, as I get older, I would like to invite people out for an evening – serve them an appetizer, a main course and then dessert. In the beginning the film appeared as a meal but also as a body. Perhaps because I was raised Christian the idea of the body as dinner came easily.

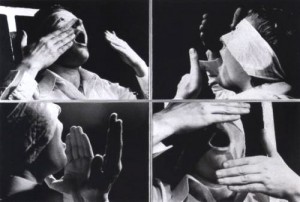

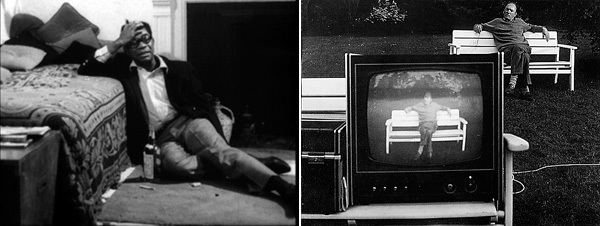

LF: In the first segment of Panic Bodies, called Positiv, you use four screens to tell the story of a man who has AIDS. One screen shows the narrator, the other three feature a barrage of pictures from a variety of sources (home movies, archival footage, Hollywood flicks). How did the idea of using four screens develop? How did you choose the images?

MH: The film reflects the condition of my body, and the illness which inhabits it, an illness which I’ve been struggling for the past decade to see as anything but an invader, as something foreign. Most of the life of my body is alien to me. At this moment, there are enzymes secreting the cranberry muffin I’ve just swallowed. There are small sea horse shaped things isolating cells hosting contagion, and signaling others to arrive, via the bloodstream, in order to attack them. My body, like everybody’s, is host to a fantastic variety of microscopic life, and while I try to ignore it as much as possible, it is no less real than what I like to think of as my ‘real’ life. AIDS has returned my body to me, no longer as the single, aging flesh suit I glimpse in the mirror, but as a hotel for dissidents, an electrical system, a complex of waterways. Lacan, amongst others, believed that our sense of identity is rooted in our bodies. We are one person because we have one body. A unified personality. But this of courser is an illusion. And so Panic Bodies, which is a narrative of the body, is a film of parts, and the section called Positiv is similarly divided, in order to offer a glimpse of the many possibilities the body offers. In order to conjure these worlds I didn’t stick sophisticated cameras into the bodies of my subjects in order to record this secret life – I simply lacked the means, so I did the next best thing – I went to the video store. And found a wondrous buffet of bodies young and old, frozen and on fire, cracking apart and transforming. I watched a lot of very bad movies, many of them made very recently, which included some lovely sequences begging for new homes. It was time to begin recycling, to bring my blue box to filmmaking.

LF: Can you talk a little bit about the technique you used to achieve this effect?

MH: It was made possible by the good folks at Charles Street Video who granted me a residency where I was able to work on an AVID. Because I’m too simple to learn anything so difficult, I worked with a number of editors: Elizabeth Schroeder, Wiebke von Carolsfeld and Dennis Day – who did all the tech stuff. As well as making suggestions of course. The multi-screen thing is very easy on an AVID, you just press a button and it happens. Or that’s how it looked to me. Making video is very anxiety provoking, because up until the moment you’ve finished you have nothing. It’s just a bunch of zeros and ones in the computer. When you’re through you ask the computer to send all these numbers to a videodeck. And then you have something you can hold in your hands. I took the tape to Exclusive (kindest and most approachable folks in the lab biz) who transferred it to film.

LF: I’m curious about the techniques used in 1+1+1. The same footage is repeated three times, each with a different look, moving from images which are heavily manipulated and degraded to the final sequence which becomes more ‘realistic.’ How did you achieve the different looks? What was the motivation behind the technique?

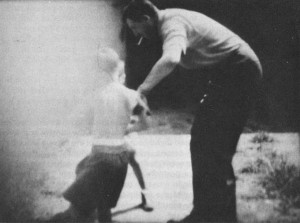

MH: Have you ever had someone swear their undying, life-longed love for you? Only the way you part your hair is dumb, you don’t know how to talk, your friends are stupid, you move with all the grace of a filing cabinet. Everything is a problem and requires changing. That’s what 1+1+1 is really about. It was edited in-camera, photographed a frame at a time with a couple of friends: Jason Boughton and Kathryn Ramey. They meet warily, then retire to the kitchen and begin to work themselves over with hand tools, trying to reshape the other into something more pleasing. Exhausted, they don each other’s clothes – he wears a dress and she puts on a suit, and fly off together to the strain of Strauss’ Blue Danube Waltz. When they meet they want only themselves, unable to see someone else standing there. It’s only when they’re able to look at things from the other’s place that they can find one another, and happiness.

The film’s repetitions derive from this circle of ourselves, the small rounds of personality most of us use to negotiate the world. It begins in hand-processed/coloured negative, and looks pretty murky. There are images of course, but it’s hard to make out exactly what’s going on. The second repetition makes things slightly clearer: now we see the negative sandwiched with its positive. The drama of this couple becoming more evident. And finally, in the third sequence, we see them in full colour. The veil of the material lifts, miming the movement of their own blindness, their ability to convert everything in the world into metaphors for themselves.

How was the film made? I was visiting friends in Seattle for a week, and we wanted to make a film, using whatever means were at hand. They were babysitting an optical printer so we took the camera/motor of it and used that to shoot with. They had one roll of colour film in the fridge. It took three days to shoot the roll, one frame at a time. No editing. I took the colour print to the B/W Film Factory, asking them to make a b/w print off it (which makes a negative), then gave that to Carl Brown, local maestro of the home chemistry set. He processed and added colour, and I used that for print number one. Then I went back to the lab and had them make a positive print of that, sandwiched it with Carl’s original to make print two. Print three was the original.

LF: In the second short sequence from Panic Bodies called A Boy’s Life, a man is searching for his lost penis. The lost member seems to be a metaphor for a void in the man’s life. In regard to your work in film, have you filled the void? Have you accomplished the things you’ve wanted or are you still searching for your member?

MH: Why did Freud think that penis envy is exclusive to women? So far as the void goes, painting and writing bring their makers to face emptiness. When they begin work their canvas, their pages, are empty. Movies are just the opposite. As a filmmaker I begin with everything, every image, and from there I make a choice. Filmmaking is like shopping. It’s a question of choosing.

LF: Many people interpret your work as autobiography. You seem to distance yourself from labeling your work this way. Do you feel labels are a type of confinement?

MH: I think our own naming is the beginning of a sentence which ends when we die. Naming bestows power – you can’t get anyone to pas you more chocolate cake if you don’t know the words. But naming also takes the place of seeing. The table I’m sitting at now – I haven’t seen it for years. The chair I’m sitting on, the electric lights – they’ve all vanished long ago, hidden beneath their names. What begins as a vantage from which to see the world, an outlook becomes the world. The look becomes the view.

Nowhere is this more true than in fringe efforts of any sort, it’s odd. When Martin Scorcese makes a movie filled with gore and aimless slaughter no one asks: Marty, do you feel like sticking a shotgun into the face of strangers? When Atom made Exotica I never heard reporters ask: Atom, do you spend most of your time down in strip clubs? Would you like to fuck school children? Because money grants their pictures a different kind of stage. A different view. On the micro-movie level we work at everything’s assumed to be autobiography. The lack of money becomes equivalent to a lack of imagination.

On the other hand I think it’s true that there are diary moments in my work. Because I lack the resources of traditional cinema – of skilled technicians and wondrous machines that provide smooth tracking shots, I have to use what I can. In order to plug the holes in the work, I sometimes have to stuff them with the material of my own life.

LF: During the discussion at the end of the premiere for Panic Bodies you said, “The unlucky ones are left behind.” What inspired you to make that statement?

MH: Looking at the audience.

LF: You also mentioned that in one sense, HIV/AIDS was a peculiar blessing for you, because it allowed you to see things in a different way. How do you see things differently than you used to?

MH: Like most people, I would rather hold onto the last miserable bit of unhappiness in the world rather than change anything in my life. Becoming positive ended that. I didn’t have a choice any more. Others have taken different roads to the same ends. Having kids for instance. To each their own crisis.

LF: Because of its episodic structure, Panic Bodies give the impression of being both open and closed, heterogeneous and homogeneous. Was that intentional?

MH: I think I intend very little with my work. Instead I follow, I give in, I search. I feel the work exists entirely independently of me, long before I show up to sign it. My task is to go to the place it already is, and this is not a rarefied space, a difficult place to get to, but most simply aren’t interested. It just doesn’t occur to someone else to go. And most of this traveling, which we politely call filmmaking, is really little more than errands, no more or less difficult than keeping an apartment running.

LF: In addition to Panic Bodies , you recently released a book Plague Years, which is sort of a compilation of scripts from your films. It also features an amazing filmography. How did the idea for the book develop? What sort of things did you have to think about when adapting the scripts to a purely written form?

MH: The book owes its publication to Steve Reinke, who asked me to write it. Between finishing his next forty videos (they’re incredible) and teaching full-time in London, he also edited the manuscript, suggesting that it take shape as a pseudo-autobiography. Using some of my film scripts as markers, I began to write around them, constructing the story of a life that mixes fact and fantasy. As I like to do all my serious reading on the toilet, I tried to keep each of the stories short, so it proceeds in episodic fashion from John Wayne playing Hamlet, to Jerry Lewis’ unexpected appearance in film school, into AIDS, Frank’s Cock, and beyond.

LF: After going through Plague Years , I have to ask you, did you really make out with Madonna? It seemed real when reading it.

MH: I owe her everything. She was my first and best teacher.

LF: How did it feel seeing your picture on the cover of NOW Magazine?

MH: Mostly it felt like there were a thousand strangers perched on my balcony wondering why the channel they were watching was so dull. But when I could see past the anxiety I began to long for the life of the person in the photograph. I began to envy him. Why? Because his story had been told. Because he no longer had to worry about what he looked like in the morning – which is the time of day when the body’s infirmities are most pronounced, when young children are already teenagers, and the middle-aged residents of old age homes – because he would always look the same way. He had decided how to appear, and beneath his look was a story which could be told and repeated. Looking at this photograph, my photograph, I saw someone who had embraced the limits of himself, who would no longer by embarrassed or ashamed to arrive at a party without a word on his lips. There was closure here, a sense of limits, and a rare certainty. Andy Warhol longed to be a machine. I’d like to become a picture.

LF: In your more recent films like Frank’s Cock , Letters From Home and now in Panic Bodies, discourse has become more explicit (actors speak, text appears in a variety of forms). How does meaning and experience relate in your films? What is their relative importance?

MH: Mark Twain remarked that experience is like a toothpick. Once you’ve had it, no one else wants it. On the other hand it’s all that most of us have – it’s the pigment, the clay which makes reproduction possible. For myself, I never spoke for the first twenty years of my life. Because I found looking and talking incompatible. Cinema helped. I arrived as an invalid and its machines of hearing and seeing slowly admitted, even insisted, on this marriage, this is the phrase filmers use, the marriage of sound and picture.

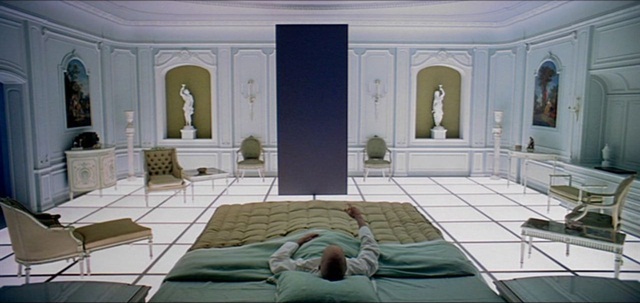

One is never alone in the cinema, or behind a camera. I never have a sense of making an image because everything has already been doubled, and I imagine these doubles residing in a place like the one described in Blade Runner as the off-world – a planet of replicants, photographs and recordings. From this infinity of pictures that is already there, from the world which already presents itself to me as an image, I make a frame, admitting so much of this face, so much of this building. And with language it’s the same. I never use a word for the first time. I say it again, my mouth an echo chamber. This is how history inhabits me, insists on being heard, just like my genetics. It’s my face, isn’t it? Only the nose belongs to my grandfather and my mouth to my mother. Even when I’m alone there’s a group scene, largely comprised of the dead. The dead are always speaking.

LF: Once we’ve questioned everything that can be questioned through filmic means, what will be left to question? In other words, what is the future of experimental film?

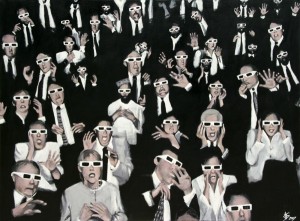

MH: The future seems to me all that is unthought. That cannot be thought. On the other hand it seems clear that the days of mechanical/chemical cinema are nearly over. Soon to be replaced with a digital understanding which signals not just a change in technology but in consciousness. When ‘movies’ are interactive, 3D and wired into the skin which will appear more true to life: the thrillers of Hitchcock or the flicker films of Paul Sharits? What pictures will be useful to the citizens of the unnamed country that is the future? Perhaps it is precisely those picture that seem so marginal, so useless today.

Interview with Mike Hoolboom by Cameron Bailey

Originally published in Lux ed. Steve Reinke and Tom Taylor (YYZ/Pleasure Dome Books, 2000)

Cameron: There’s a quote in Panic Bodies that has stuck with me: “My body keeps getting in the way.” It seems that your work now depends more and more on the body, and on your body in particular. It’s like you’ve moved from films about ideas— White Museum , Grid and others—to films that are more direct, more visceral.

Mike: I think my early movies were a long handshake with the medium, trying to figure out what it was about, what you could do with this room that’s dark with light up front. But after becoming positive it’s become incumbent to make work that tried to deal with mortality and this very odd new place my body was in, that had been, as I say in the film (Panic Bodies) a kind of unifying locus for my identity.

You look in the mirror and you’re one person because you’re one body. But all of a sudden, you’re not one body anymore because parts of you are filled with something foreign. So maybe I’m more than one person. In the act of contagion where does one body end and another begin?

I had this dream over the weekend. I hardly ever remember my dreams. I’m in the basement of a large factory, below ground. I’m busy putting together pairs of buffed metal pieces. One of them has a small stick shift on it. It’s a very satisfying motion. They snap together with a magnetic charge. I do this over and again on a long conveyor belt and as I do I realize that all the things I do in my life-whether talking to friends or falling in love or answering the phone-all arise from this action. It all begins here.

At this moment the camera zooms out and I see many others doing exactly the same thing. We’re all putting our little metal pieces together. I am filled with a great feeling of communion and solidarity. We’re all one person!

At that moment the spotlight arrives and a blank net scoops me away. I look down and see I’ve been replaced by a machine that performs the same action, it’s putting together the small metal pieces. I scream that no robot could ever do what I do! But of course it can.

Cameron: Can you talk about how you first discovered your HIV status? You’ve said the problem was not how to die but how to live.

Mike: I was informed by a doctor who knew nothing about it. He said, “Well, I picked up some pamphlets…” It was early days then, and there was no treatment of any kind. He knew nothing about other doctors who specialized in these matters, or support organizations so I was very much in a dark I gathered to myself. I wasn’t certain how to proceed though I imagined the end was not far. It fit with how I was living anyways, sped up and thoughtless and drinking too much and not too… reflective. I tried to repress as much as I could and kicked the accelerator into everything I was doing. Made more films. I was working at Canadian Filmmakers then and got a lot of work shown and started a magazine and Pleasure Dome and involved myself in arguments I imagined were important and principalled. I look back and they seem so small minded but we’re all so much younger now. It took leaving Toronto to achieve distance, shake the habits and start over. I moved to Vancouver, a city where I knew no one.

Cameron: What made you do that?

Mike: Well, my counts were failing so I had to do something. By that time I’d found a doctor in Toronto I liked very much but in retrospect he was a bit laissez-faire. The fact that my counts had dropped by half in the space of a year didn’t set off alarm bells. This was before there were any drugs available, so when you fell below a certain T-count level opportunistic infections could really get a grip. But of course with an all-AIDS practice he’s watching people that are a lot worse than I am. I’m still strolling in on my own steam so I seem alright. I can’t imagine being a doctor before the invention of the cocktail, each and every patient getting worse while you monitor their decline, listen to them talk about symptoms that hadn’t been seen in humans for decades, and then watch them die.

Cameron: What did you do when you got to Vancouver?

Mike: I’d been working at Canadian Filmmakers so I collected unemployment insurance when I left, which was enough to live on. Vancouver had a series of very cheap downtown men’s hotels which were occasionally dangerous and invariably roach infested. , I got a room on Granville with a hotplate and a little bar fridge and lived out of a knapsack. I bought a six dollar transistor radio and started listening to the CBC and wrote the script for Kanada. I thought okay, this is my life now.

Cameron: What made you come back to Toronto?

Mike: I’d done my penance. It was time to be near people I knew and cared for. I’d had enough of wandering in the desert and I think I’d found a new place for my work.

Cameron: You entered a period of accelerated work then, making film after film. How does that work look to you now? Do you feel like you took a false step?

Mike: I always feel like I take false steps. Many people start well in the movies. It’s not unusual that people arrive and make something perfect the first time out. I was not one of those people. I made many many films before arriving at something watchable.

Cameron: What’s the first thing you thought was watchable?

Mike: The first film I made that I like? It’s hard to know. I like the film that Steve and I made called Mexico, although it’s slow and ponderous. Kanada is very in your face… I recut it though, it’s better now, I don’t know, I’m not that happy with anything. Even the new one I’m going to show (Panic Bodies), I know at last what’s wrong with it. I keep feeling like I’m going to get there, but I never get there.

I was not born in the cinema, you know. I’m just one of those people that has to work extra hours with great diligence and at some point it will start coming together. Slowly the fog is lifting, though I have an uncanny capacity for self deception. Oh look, it’s finished. I always begin at the end, and proceed with perfect confidence and happiness. This is generally followed by a brief honeymoon period (never again will another movie need to be made!), followed by a sober reappraisal and complete rejection. No, that won’t do at all. Once recast in this new light, the work is returned to with a renewed clarity, of course of course, now I know what’s wrong, and I begin again to retool it with great confidence and energy, racing once more to the end. And then I’m finished, another perfect film has been made… until I realize no, not only is it not perfect, it’s not even a film yet, it requires yet another massive remaking… and so on. It has taken some years to become clearer that this has become normative.

Cameron: That’s surprising to hear because it always seemed to me that film was your medium and language.

Mike: I used to write a lot and then decided I would make films. I’ve often wondered if it was one of those things you do because you see the good road and the hard road and you think yeah, the hard road, that’s for you. Because that’s what you deserve.

Cameron: So you’re punishing yourself by making films?

Mike: (laughter)

Cameron: I’m interested in your use of the term “fringe film” as opposed to “experimental” or “avant-garde.” I’m especially interested in the economy of the avant-garde. Is money what makes a film fringe?

Mike: To me “experimental” means people in white lab coats, investigators holding an object under examination and asking, “What can it do?” The only thing that’s avant-garde is commercials. People with a lot of money seem to be in the avant-garde because they know where we’re going. It’s the 90s and people are following money. And yet there are eruptions of dissent and that seems to belong to the fringe.

Cameron: You worked at the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre, you’ve been a critic, a magazine editor, a curator. How do you see your role now? Is it your job to produce stuff, or do you feel a responsibility to play a larger role?

Mike: The museums said no, the art world turned its back, the labs closed, the universities and art colleges rent work but there is no body of critical writing massing anywhere. Where are we, the underground? If there were others writing and collecting and showing what a relief that would be, taking care, tending to it. There are some of course, Pleasure Dome continues to roll, and the Images Festival, and spasms of events. I wish I could stop but. Experimental film is so valueless now. Its ideals are part of another time, it’s a hangover from the 1950s, some quaintly beat, pseudo-anarchistic thing. These are clearly the last years for celluloid.

Cameron: Really?

Mike: There’s only one lab left in town that can make colour prints in 16mm. There’s one man left who knows how to make opticals. The industrial base has fled and artists will never make it up, instead we’ll turn to either 35mm or video. For most that has to mean video.

Cameron: What does that mean for a filmmaker like you?

Mike: You have to go on. Hopefully the cheap tech will make work possible for different kinds of makers.

Capital is so strange. There is no middle class in movies. There are the movies everyone knows, and there’s everything else. At least on the fringe people are actually working on their lives and their images and their materials instead of chasing a dream of making the big score.

It’s so hard to make a good film and there are so many things that can go wrong. When you start accumulating big sums of money it’s that much harder because money is conservative. Money always wants to do what’s already been done before. And most of what’s been done before is not that interesting.

I think of mainstream film like going to see a friend from high school. You can talk about a shared night at fifteen. You get that little flash of, “Oh, that was funny.” But then you return to your real life and that little flash has nothing to do with it. That’s when fringe film arrives. It’s for when you wake up in the morning.

Cameron: How does this affect your relationship with your audience? Is there always a direct engagement with the people out there?

Mike: There’s more of an opportunity to show now than ten years ago. There are so many festivals, where did they all come from? There are places for these small moments. It’s been tortuously helpful for me to sit with audiences and watch my films exactly because they’re strangers. They haven’t arrived to cut you any slack. As I get older I’ve become more impatient. I can’t sit and watch cameras turn for hours or watch grain flicker across a screen. The time for material demonstrations is definitely over now. My movies reflect some of that impatience and urgency.

Cameron: It’s about communicating rather than just expressing.

Mike: Right. With Panic Bodies for instance I took it on a test drive through Germany. I showed it in half a dozen spots, in a slightly different version than what you saw. The first section wasn’t done yet so Frank’s Cock played there instead. And the last section, Passing On, needed some work, but I didn’t know that yet until the final screening in Bielefeld, that’s when it became clear what was missing.

Cameron: From how the audience responded?

Mike: You feel their feeling. You become them. Wanderings of attention, points which sail through the room without landing, or “Oh, they thought that was funny.” I recut Passing On a lot, starting with the music and sound effects and I did a lot more shooting until the whole picture was reworked. Then I showed it in Ottawa and realized that the second section (A Boy’s Life) wasn’t working, it was too long. It took me that many screenings to be able to see it. So it was recut and is a lot tighter now.

Cameron: Some filmmakers would be aghast at the way you’re talking-that’s what the market does, not what you’re supposed to do. You’re an artist.

Mike: Well, actually I read a book on Fellini and it was common for him to do exactly the same. He’d finish a film for the Venice Festival for instance, and it might show here and there, and then they’d sit down and recut it leisurely. The recut version is the one that everyone knows.

It’s expensive though. I’ve spent most of the last three years recutting my films. House of Pain is down to fifty minutes from eighty. Kanada is down to fourty-five from sixty. Valentine’s Day is going to become part of a composite film. It was cut from eighty minutes to eighteen and it’s got a new opening and video inserts. It’s become something completely different.

Cameron: So which is the real version?

Mike: The new version is the real version.

Cameron: You’re going to fuck up the scholars.

Mike: My body of work is shrinking rapidly. Every year I make less films, cumulatively. It came partly out of interviewing filmmakers and going back to their bodies of work and seeing things that had thrilled me a decade before and realizing that they just didn’t hold up. Or all you can look at are people’s sideburns. Films do not age gracefully.

Cameron: Your recent films show a real engagement with pop culture.

Mike: There was a time, capped by the period when I worked at Canadian Filmmakers, when I didn’t talk to anyone who wasn’t making, seeing or writing about fringe movies. That was fine for a while, but it’s a very unreal, abstract place. It was also founded on a strangely adversarial hierarchy. “We” were going to change the way “people” see, there is a politic inherent in perception itself and on the argument went. Hangover rhetoric that has been proven irrelevant beneath the steamroller of multinational capital. What else can you show us? “Oh yes, we can make a NIKE commercial out of that.” Handprocessing? The National Football League uses that for its promos now.

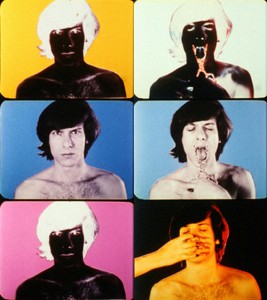

I grew up on the nipple of televison and simply started up again. It’s so peculiar after you’ve been away. I had never heard of Madonna for instance until she came out with her movie, which is winningly titled in Europe In Bed With Madonna. I loved her film, in part because she’s such a workaholic and I’ve always had a soft spot for that. And whether onstage or off she is camera ready, changeling, poreless, camera top.

It’s more and more difficult to imagine a time when one would have to travel in order to see an image. If the captains of picture industries are so insistent that billions of us consume their pictures then it is fair, perhaps even necessary, to be able to take these pictures and recycle them. One good turn deserves a détourne.

I’ll bet at this moment I could walk from anywhere within Toronto and within a five-minute radius I could find an image of Leonardo DiCaprio. So if someone wants to take this picture and do something with it, isn’t that what they’re asking for anyway? Madonna and Michael Jackson, whose pictures I’ve been busy recycling lately, are similarly ubiquitous. I felt Madonna was the precursor to the Lewinsky affair. She’s someone for whom intimacy on camera and intimacy off camera appear to be the same thing. She’s already crossed that line, but soon we’ll all cross that line. And that’s the real significance of the Lewinsky affair. It’s not about impeachment or the presidency. It will be remembered, if at all, as the event that made private public. “I’m not going to come in your mouth because that’s too much commitment for me.” That’s real intimacy. This is, this is your president speaking.

I think we will watch our neighbours on tv, having arguments, having sex. It will be a completely visible and televised society. Madonna is one of the great harbingers of this change.

Cameron: This what also interested me about how you used stars-underlining their bodily transformation. Tell me about Moucle’s Island. It’s an interesting collaboration because it’s so female.

Mike: I met Moucle in Australia though she lives in Austria, the kingdom of experimental cinema. They have a distribution outfit named Sixpack who do everything but make breakfast and your next movie. They send work to every festival known to humankind, and produce postcards announcing your movie is done, and then sell it to television. I’ve seen three books in the past three years on Austrian fringe movies. So there she was, the latest emissary from the pleasure dome of the fringe, showing movies though she seemed a bit lost at the same time. Part of it had to do with her body, did she say she was in the wrong body? She showed a film I like very much called OK (Oberfleischen Kontact), a diary romance projected and refilmed entirely in her hand. At the end of the film her hand closes and opens and the film drops away in little bits of plastic. Oh, it was nothing, just an affair, a few days, a moment of light.

Cameron: Let’s turn back to your films. I’ve noticed an evolution from a kind of transgressive heterosexuality towards a more ambisexual fluidity.

Mike: The movies have become documentaries of the imaginary. They’re more faithful renderings of how I dream, or imagine the world to be. In my dreams it’s commonplace for me to present as a woman who becomes a man who is getting it on with a woman who becomes a man. Gender is rarely fixed and that’s increasingly reflected in the work.

I remember thinking that even though many people have died terrible deaths in Martin Scorsese’s films I never hear him asked whether he harbours serial killing fantasies. After Atom’s Exotica I don’t remember anyone asking whether he’s a peeping tom, or whether he enjoys spending weekends in strip clubs. But if you’re making on a modest budget and below a certain threshold of visibility, it’s generally assumed that the work is directly autobiographical. No money equals no imagination. Why, if he had any imagination, he’d be a rich man, right?

I think this condition is especially confusing with someone like me, where obviously autobiographical material is pressed into service in the same way as a Madonna clip. Traditional identity politics privileges a documentary expression: this is who I am so this is how I must represent. But in a more imaginary media world, which is where all of my movies are set—and I don’t think of that as being less tangible, in fact, I think the imaginary is where many of us really live—I think it’s a lot harder to identify.

Cameron: So who shows your films now? The queer cinema circuit or experimental venues? Is your work being taken up in a way that is confusing to you?

Mike: Mostly I don’t follow my movies around because I don’t like leaving my apartment. They play in cities I can’t pronounce and I’m grateful they do. The question of publics has been fictional and imaginary, especially when the theatre is full and I happen to be present. My work continues to change, even the titles which are fixed and finished are being rehauled. I suspect this may continue. The new movie is about children but if you asked me why I couldn’t really tell you. Why are you wearing that shirt? Why do you have that look in your eye when you see your favourite chair? Sometimes it’s a question of going where your heart takes you.

![01-madonna-immaculate-collection-lashes-by-w7[4]](http://mikehoolboom.com/thenewsite/wp-content/uploads/1998/06/01-madonna-immaculate-collection-lashes-by-w74-300x181.jpg)