House of Pain interview (Berlin 1995)

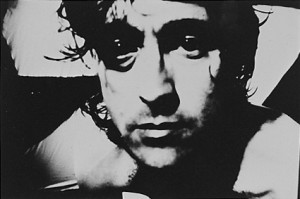

Springtime in Berlin. I’m here to show my new movie House of Pain , a wordless psychodrama filled with every imaginable transgression. The press isn’t good, it’s fanatical, especially in the East where my movie appears as a lighthouse of “Western freedoms.” A secret history of sex and Marlboroughs and Levis three decades of secret police couldn’t quite keep under wraps. For a few days, or hours, I’m Berlin’s number one son, part of that underground currency of hard-bodied singers and glammed-up ex-junkies living and dying beneath the glare of the flashbulbs. Sprechen sie Canadian?

This morning I’m off to Zoom, a morning cable show for those needing company with their coffee. In North America we speak of the inner child. In Berlin it’s the inner skinhead. My suitably hairless attendant arrives in a three piece suit and nose ring and I start from the chair, thinking it’s Michel. An old habit. Arriving in foreign cities, I begin to map the faces of my friends onto everyone I meet. Not out of any longing for home, my brain’s just grown too small to admit anything new. “This way please.” He motions towards the waiting room where a half dozen cats are jumping up on the lap of their owner (Zena and her amazing cat circus), while a bored fisherman, covered in lures and bait (Jurgen the whale hunter) rolls a small ball of what looks like chewing gum between his fingers. Everyone smokes.

Twenty minutes later I’m ushered in, the band playing an acid jazz number that never quite stops while I’m talking, I can see the floor manager trying to get their attention but it’s no use. They’ve found their groove and they’re keeping it. The host is a large free-standing box—some kind of computer I guess—that’s programmed to burp, fart, emit steam and flash its siren while you’re talking. It speaks perfect English in a low voice that sounds like Darth Vader with a hang-over. Mostly I look at my shoes.

“Thirty years ago we all dreamed of living in the movies. Today we long to live on television. Is it the same in your country?”

“TV is the hole where pictures come from. The eye of the tribe. It’s why we can say we. We want. We think. I walk down the street and see that everyone is dressed, not alike, but as part of this time, we’re dressing for our moment, our close-up, but a hundred years ago these same people, wearing the same personalities, would have different clothes. When I look out, it’s hard to see other people, what I’m watching instead are the effects of television.

“How dull and tedious you are. Tell us about your new film without boring us to death.”

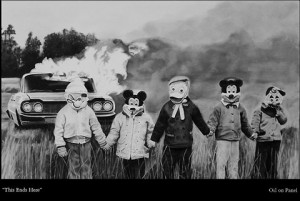

“House of Pain is a wordless movie in four parts—like a sitcom without the calm. It began with ideas cribbed from Dante’s Inferno — he shows the underworld as a descending series of circles with Judas stuck in a frozen lake at the bottom. The lake acts like a mirror, so all of hell is caught in its own reflection. While there is incessant movement in hell, each circle corresponding to some sin committed, these folks are always doing the same thing. Today we have other words for hell. Like “day job,” or “morning routines” or “love.” Most of us, most of the time, are repeating, leaning on the learned, the received, the accepted to get us through the day. This is especially terrifying when it comes to intimacy, when going over an old stroke is how we’ve learned to fuck, express anger, be happy. We’re like actors that way. We repeat.”

“What about Shiteater ?”

“Like the human heart, House of Pain has four chambers. Shiteater is the last. It shows a man waking, dumping and eating. Then he dresses in threads copped from medieval plague doctors who dared to enter cities locked in quarantine. Equal parts showboat, religious mystic and scientist they dressed in bird costumes and performed rituals to heal the sick. When they didn’t die themselves. Finishing his dress-up our man begins to play with his body, taking an egg out of his mouth, then opening up his underwear to find a rooster, which turns into a cock. He orgasms. The film closes in the ocean where he strips and emerges naked. Reborn. The shiteating describes the circle of himself Dante writes about. He’s become his own food, happy to consume himself. In his solitary, the body’s become a world of play. He sails to the end of this world where he is baptized into a new one. Ready to begin again.”

“The opening and closing parts, Precious and Shiteater , show individuals, while the middle two films Scum and Kisses show couples.

“The journey begins and ends alone. Kisses shows two men who behave like many lifetime partners, relying on masquerade and game playing to hold it together. They piss, torture, beat and shave each other and wind up in a playground, just two big kids out for a laugh.

Scum narrates a het couple who are seen mostly alone, haunted by images of their marriage. Their sex belongs to a world of objects: she fucks her bike, he mounts a cauliflower. In most movies romance enters when each appears to their beloved in the best possible light. But Scum shows how things are more likely to occur, both partners find the worst in themselves, exploring the dark side, and when they’re right at the bottom they look up and see the other covered in shit and horror and say okay. I can live with that. It’s only then they come together and kiss.”

“Charming, a Canadian documentary on love. What’s next?”

“I’d like to make useful films. Films you could eat or wipe your nose with. I envy porn for that, it’s such a practical mode of filmmaking. When I make a piece of work I feel it already exists, independently of me. It requires listening, going to where it already lives, like an unfinished house. This house already has a shape, which insists the door be put in a certain place, and the windows another. That’s my job. To be able to give shape to the wonder and horror of this living, this body, that’s what I’m trying to do next.”

House of Pain: an interview with Noam Gonnick (1995)

Mike Hoolboom’s films, including Frank’s Cock and Valentine’s Day , deal with sex and sexuality in a startingly frank and open way. The Toronto-based artist was recently at the Cinematheque to attend a retrospective of his work. He spoke with local filmmaker Noam Gonnick about his most recent piece House of Pain .

Noam Gonnick: What is House of Pain about? I was looking frantically through all your support materials for that one explanatory paragraph, and I couldn’t find it anywhere.

(long pause)

Mike Hoolboom: Oh, what’s it about?

NG: Yeah. Like, is it just some sort of ah… an encyclopedia of sexual fetishes. (laughter) Because towards the end I began to think: there’s that one, there’s that one too…

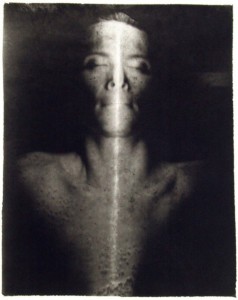

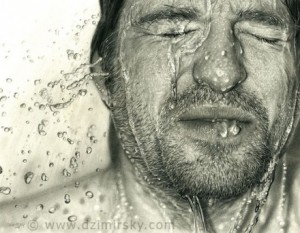

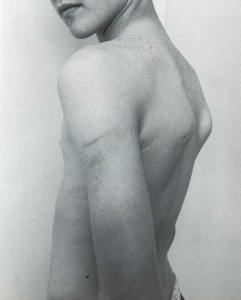

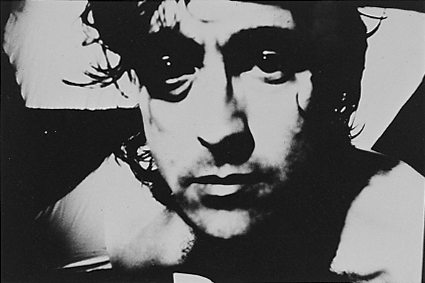

MH: Well, it’s a series of four interlocking, psycho-dramatic films, all photographed the same way. All shot close-up, fetish-style, super high-contrast black and white film stock, all involving relationships and power. Do you want the whole rap?

NG: It sounds like that’s what I’m getting.

MH: The last film, Shiteater, shows a guy doing what we all do: he gets up in the morning, shaves, he puts on his clothes, takes a shit and eats it. That’s part one. In part two he puts on this outfit—stockings, tail feathers and bird mask based on a medieval practice. In the middle ages plagues ravaged many city states which were then quarantined, and these brave hearts entered as doctors (one part alchemist, one part medicine man, one part scientist), talismanic figures who performed what were imagined to be cures for the plague. Andrew’s character was based on these figures. Then Andrew worked up an egg rite: an egg comes out of his mouth; it reappears in his pants, then this egg becomes a cock. He jerks himself off, and his ejaculate becomes the white ocean where he strips and washes it all away. It’s a baptism of sorts. The film is about someone who lives alone. Solitary, doesn’t want to answer the telephone, or unlock the door. You lock yourself up and start feeding on yourself. You are the world, as large as your body is. So you start playing with and transforming your body.

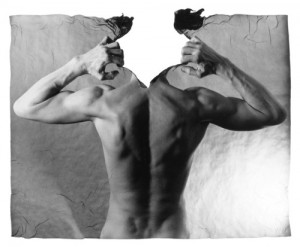

The third film, Kisses, is about two men in a series of sex/play tableau. The original version began with Ed dressing as a woman and walking his dogs out by the railroad tracks where Paul is lying passed out. Ed fucks him there while the dog licks his face off. In the next scene the power roles are reversed, Paul cuts glory holes out of a zebra striped sheet and gives Ed a blow job. In relationships power changes. This is underlined by the closing scene where they end up at the playground, laughing it all off.

The second movie is called Scum, and narrates a het couple. The central object in the film is a double-sided compact mirror, a mirror which mirrors itself. They’re both fascinated by this object, both of them caught in the reflection of themselves. Even though the movie is about a couple, mostly we see them individually. They both perform long masturbation scenes, she with a bicycle, he with one of those vegetables, what are they called?

NG: Cauliflower?

MH: Cauliflower, yes that’s right.

NG: I think he made cauliflower soup out of it.

MH: Right, the rice pudding scene. They are both haunted by the image of their union-scenes of their marriage recur but they can’t handle it. It’s not until they both come to the bottom of themselves, that they can look up and see the other person, who’s come as low and you can go. And at that moment they say to one another, “OK, I accept you, even like that.” Then they kiss and make love: another happy ending!

The first movie called Precious is about someone who enters a graveyard and you can see right away that something is missing. This person wears an eyepatch, and over the course of the film the eyeball appears in different places. A series of rituals, one in the graveyard, one by the seashore, and one with a bucket. In each instance she conjures up the eye and then tries to stuff it back into her body. She wants to become whole, unified, to become one person again. And yet this is a part of herself that can’t be so easily integrated. In the end she takes her eye in hand and walks towards the water. It’s a moment I imagine as reconciliation, that she recognizes herself as a body of parts but that’s OK.

NG: OK, here’s a stupid question and then we’ll finish. I saw House of Pain and loved the imagery and loved it, period. But my whole summation was that it’s an encyclopedia of fetishes. Then you give me this beautiful, complex reading of each segment. The question is: do people catch your meaning when they watch? Does that really matter to you? Do you care?

MH: Could I answer by using a story from (American composer) John Cage who might have been asked the same question?

NG: Sure.

MH: It’s 1955, John Cage and (choreographer) Merce Cunningham are on tour in the US. You can imagine what the response might have been like: music that doesn’t sound musical accompanyiing dancers who don’t look like they’re dancing. So one night they had a gig in Washington and the bus is delayed and then it breaks down, and when they finally arrive the equipment malfunctions, the dancers haven’t slept a wink, no one’s making their cues and the jumps are more like shuffles. Ok, we really bit it tonight, let’s get out of here. Cut to fifteen years later, John Cage is presiding over a presentation of his latest work. Afterwards a young woman shyly makes her way across the floor and says, “Mr. Cage? I just wanted to thank you for that performance fifteen years ago which I saw. It was so stunning that I decided to become a dancer.” He said, “You see? You just can’t tell.”