What He Said: an interview with Mike Hoolboom by Dirk de Bruyn (Vancouver, 1993)

D: Before you came to Vancouver you worked for a time at the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre in Toronto.

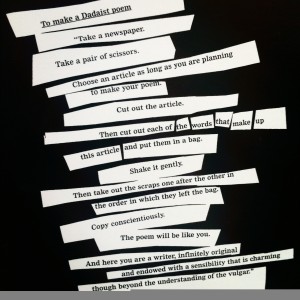

M: Canadian Filmmakers is Canada’s oldest artist run centre—begun by a group of disgruntled filmmakers (including David Cronenberg) in the sixties who were making work with no place to show them. So they decided to form a filmmaker’s co-op which would accept any kind of film no matter the subject or genre. That’s pretty much how it remains. When I arrived there were about a thousand titles—half were animated, documentary or short dramatic films, half were “experimental.” I was hired to look after the unusual stuff and moved into the office, worked seven days a week, often past midnight. I organized tours, started a library, put out a festival guide, added a lot of films, wrote about movies for the art mags, had frame enlargements made of every movie in the collection and typed the whole works into the computer for a pair of catalogues. Then I started work on the filmmaker files which turned out to be a gold mine of glossalia, trivia, failed grant applications, sentimental journeys—almost all of it unpublished. At the time we put out this little updating newsletter and I wondered why not include some of this? That’s how The Independent Eye magazine started, which would eventually run a hundred pages between glossy covers and hit the newsstands. It was terrific, but lasted only a year after I left, three years in all. There are some who feel that filmmakers should be seen and not heard but I was thinking of past avant-gardes who had often written their own tickets. All that broken down phonetic poetry by Tzara or Lemaitre—that wasn’t going to get covered in Time or Le Monde. If you wanted to get the word out you had to do it yourself. That’s how I saw the Eye, as news from the other side, starter kits of refusal.

I remember listening to John Cage speak very informally at an art college in Toronto. Where someone asked him what’s the use of all this marginal work. He recounted a tour he made with Merce Cunningham’s dance group. This was pretty aleatory stuff to barnstorm in the fifties, and Cage recalled one evening in particular where everything seemed to go wrong, the bus broke down, the hall was too small, lights didn’t light, the dancers were tired. After the show was over they chalked it up and pushed on. Cut to a state ceremony dinner some dozen years later. Cage is making his way through a plateful of mushrooms when he is approached by a young woman. “Mr. Cage?” “Yes.” “I just wanted to tell you that I saw a concert of yours once in Minnesota.” The concert he would never forget, the low point. “Yes, I’d never seen anything like it. I was so inspired that I’ve become a modern dancer.”

The work I make and the work of others I’m interested in is very small work—not in terms of ideas or commitment—but in its economy of exchange. It lives outside traditional menus of attention, of theatre chains and daily papers, and this marginal perspective allows it a freedom it couldn’t have elsewhere. The danger in this freedom is solipsism, that “avant-garde” becomes another genre like the western or the horror film. But without a social context. So it begins to implode. To restage its own history with a visual rhetoric that is increasingly difficult to follow by any but the most well versed of its devotees. I’m not against “art for art’s sake”—because there are periods when certain practices are considered irrelevant, supplemental, you see this in the art journals all the time. Painting is dead, sculpture is dead, everything’s fucking dead. But there are times in your practice, and in your life, when it’s enough to keep working quietly just to keep it alive, to keep the hope alive for something else. But that can’t go on forever.

Every day to earn my daily bread

I go to the nearest market where lies are bought

Hopefully

I take up my place among the sellers

Brecht “Hollywood”

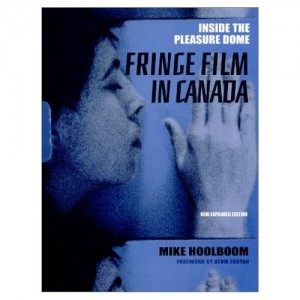

D: You have just completed a book of interviews with Canadian fringe filmmakers that includes a number of essays on their work.

M: It began as a call to arms, an affirmation of oppositional practice and personal invention. But as I’m nearing its close it’s begun to take the shape of mourning, of a lament for a practice whose days are clearly numbered. It’s heinously expensive to make films these days and many of those traditionally excluded from even marginal modes of expression—women, people of colour, gays—have an abiding interest in narrative practice because their experience must be accounted for, their stories too long ignored given shape. There’s little return in making fringe movies—there is little press or audience or awards and that doesn’t seem to matter as much when you’re twenty. But what happens when you’re fourty and you still can’t make the rent? And every ad known to human kind is saying you should be living better than you do. Most of the people who were making films when I started have kicked the habit, and each year fewer begin.

D: How does the writing of the book fit in with this?

M: The book is an extension of the gesture begun at Canadian Filmmakers, of adding words to pictures, and attempting to conjure for those unused to any but the stars in Hollywood this different kind of production. You could make an analogy between film and the spectrum of light; the visible part of the spectrum our eyes are tuned into is actually quite narrow. But the spectrum continues with great range and variety on either end of this rainbow, producing x-rays, ultraviolets and radio waves. They exist even though we can’t see them. I think of the visible spectrum as mainstream film and the rest of the dial like fringe film: the unseen, the marginal and repressed. The book was intended to make visible this other kind of light. I interviewed eighteen filmmakers and called it Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada . Half the filmmakers are men, half women, and roughly half hail from Canada west and half from the east. The focus throughout the interviews is on the work. Many offer close textual readings of films that are just a few minutes long. Because a lot of thought goes into these things. A lot of living.

D: Most of these makers are avant-garde or… what do you call it? When you write you’ve used the word avant garde .

M: I was doing a lot of that working at Canadian Filmmakers because I hated the word “experimental.” I was representing a collection of some 500 films which I would occasionally trot out to librarians in far flung school boards. Never having seen anything like it they hated this stuff and their feelings seemed exacerbated by the fact that they were called “experimental” films. It was a pejorative term of dismissal. I was also concerned about the increasing institutionalization of Canadian art practice and the degree of state dependency. Artists rely on the state for production grants, then go to federally sponsored distribution organs which push work to federally driven exhibition houses. By using the word “avant-garde,” I wanted to recall a history of resistance and opposition. Though I was a little taken aback at the American use of the word. They casually refer to the whole field as “avant-garde.” Can you imagine sitting at an editing bench and thinking “Well now it’s time make a few more pounds of avant-garde film?” Avant-garde speaks of a state of mind which for many no longer holds, so in order to keep this resistance active, I wrote “avant-garde” when referring to films of this sort, but also to show its problematized status—the difficulty of making something truly “avant-garde” today, I placed the word under erasure. Hence avant-garde .

Fringe film is founded on a number of paradoxes. It’s a machine art founded on the premise of infinite replication, yet most artists can’t afford to make more than a handful of prints. It’s an art of motion pictures yet all the pictures are still. And finally the industrial aspect of these pictures, the dream factory, is so important for our industrial consensus that everyone has some experience of the movies. Yet with people lined up around the block to catch the latest flicker from Arnold or Madonna there is virtually no interest in the movies made here. A situation not unique to Canada, it’s the same in Tokyo or Brussels or Melbourne, they’re all playing the same American films.

D: Yes, I find that a very marginalizing process.

M: The great irony of being an artist who uses film is to gain access to the machines of production while being refused the machines of distribution and exhibition. This has been the single greatest oversight in Canadian film policy, the failure to understand that these three aspects of films are related: production-distribution-exhibition. I think the fringe’s greatest failure has been its inability to respond to television. The kind of invention and ingenuity applied to the work’s making has rarely been turned to exhibition. I’m not talking about brave new worlds of hype. I’m talking about hundred set video walls stacked in malls or the kind of public projection that Krzysztof Wodiczko has been doing for the past decade—constructing site specific slides and projecting them against public monuments. Jonathan Culler wrote, “Meaning is context bound but context is boundless.” The way a work is framed or presented, who it is presented to and to what end—all of these things change a work. I don’t think there’s any such thing as a bad film, there’s only a wrong place and time to show one. It used to be that we thought meaning was contained in the work but now we understand that the work is part of a social relation that is always changing. Always alive.

I think the art “world” has been responsible for the idea that the avant-garde exists as a restless interrogation of forms. But a real artist, someone who isn’t just making work out of a recipe book, is trying to figure how to live. They’re inventing, making it up as they go along, informed by the rabble of every direction but in an expression that is all their own, like the DNA code or the lines on the thumb. When it comes out the scribes say, “Oh that’s been done before”—but of course it hasn’t, not like this. Or, if it’s valued, esteemed, it attaches itself to a name. Like expressionism. Neo-geo. Abstract. The truth is most abstract paintings or abstract films aren’t very abstract at all. They’re concrete responses to concrete situations. When they’re good that is. When they’re bad it’s just more mush on the pile.

D: How did becoming HIV positive change your film work?

M: I worked harder. Finished more films. And quite unconsciously began a series of films that take the body as its subject—putting it under tremendous strain, often through a montage which grew increasingly fascinated with a body of parts spliced and spliced again. Miming the gesture of the disease to come. I returned to diary footage shot a half dozen years before, to images of myself and an ex-lover, to pictures of a body that had not yet felt its own end crawling inside. I took simple gestures like cooking or walking down halls and hacked them together in interruptive rhythms of two and three frame cuts. These gestures of dissolution would eventually find their way into films like Was and Eat.

D: Can you say something about the process of how you make films?

M: I think my body of work ranges across two broad areas of concern: the body of film and the body of its maker. A composer would think nothing of making symphonies, piano solos, violin duets, quintets, to make work of various lengths for various situations. This hasn’t proven to be the case so much with film. There seems to be a push to be identified with a certain kind of making—especially with features which have become the exit door of the avant-garde. So far as my own work is concerned there are a number of films that relate to the machine of film— Modern Times for instance, or The Big Show (7 minutes b/w silent 1984) which simply offers up a number of titled instructions for the audience like “Please Stand.” Or Scaling (5 minutes b/w 1988) which shows me painting the frame’s rectangle black, but this image is superimposed with itself in reverse, so even as I’m painting the frame black, the other “me” is unpainting the black and making it white again. All of this work features a medium in dialogue with itself, they are an interrogation of limits, of possible futures, they comprise a kind of materialist science fiction. On the other hand there are the more “personal” diary films. Personal’s a funny word to use because everyone’s work is personal—even the most horrible, exploitative, blood-drenched thriller bears certain unmistakable traces of the hand that crafted it. And while many of my films contain explicitly diaristic footage, this is invariably deployed to ends that are quite removed from my life. Like Eat (15 minutes 1989) for instance. It’s stuffed with diary images of my former lover and myself. But once the bodies of these two lovers have been broken apart, the effluvia of a media excessive culture is poured in. These fragmented moments of greeting are overlaid with landscapes, television commercials, fashion shows, rotoscoped drawings, pornography, titles from Dante’s Inferno , movie trailers. Six rolls of pictures were printed together and these play twice in the film. In the first instance a woman relates the story of her anorexia, and in the second a man describes a fantastic eating duel lifted from Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude . The film is framed by an early Lumiére film which shows workers knocking a wall down at the film’s beginning, while at the film’s close it’s run backwards so it resurrects itself, providing a physical frame or bracket within which the images play. There’s whispers of the personal everywhere but the film is not finally my story, or some recounting of events in my life. Perhaps as Godard insists the only way to make a real fiction film is to begin with documentary, while the only way to make a documentary is through fiction.

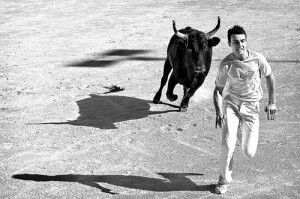

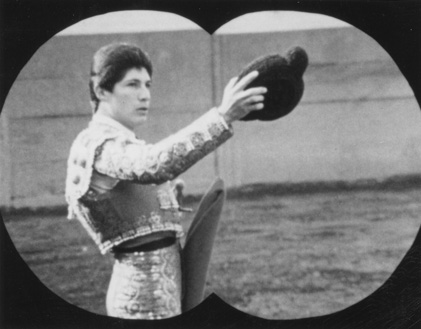

D: In Mexico (by Hoolboom/Sanguedolce 35 minutes 1992) the bullfight seems central to its understanding, though there is something almost casual about this sequence.

M: Steve Sanguedolce and I headed down to Mexico in the summer of 1989 with a carload of gear and stock. We didn’t have a clue what we might find, only that we’d shoot from the hip. We arrived in July—low ebb of the tourist season, all the major rings closed and the matadors left were all pretenders. Amateurs in training. You can’t tell at first because they’re all gussied up with pomp and pageantry. Every fight we watched was the same, while the matador tries to soften up the bull for the kill he doesn’t quite manage, the bull chases the matador out of the ring, and when he comes back he’s horned, tossed and trampled. The matador gets sponged off and returns to stab away until the bull finally goes down. He turns to the crowd, hand aloft, accepting the crowd’s cheers. But then the bull gets back up again. So the fight becomes a farce. It’s like that line from Marx which insists that everything in history appears twice, the first time as tragedy the second as farce. The fight begins again—but now as a sad, pathetic slaughter.

We used our cameras the way supermodels deploy lipstick and eyeshadow, as part of our personalities, and quickly made doubles of everything we saw before hauling our image trophies back home. Once the hangovers had passed we uncovered a mess of unconnected moments, and spent the next three years trying to give them shape. After our return, haunted by the old dreams of growing smaller, it’s as if we’d never wandered from home at all. As if the only thing that had ever left was our imagination.

The story laid over the pictures narrates a man trying to escape his past life in Toronto, so Mexico is rendered as escape and release, but also as a place where he attempts to murder his own history. The bull in this schema becomes a metaphor for all that is left behind.

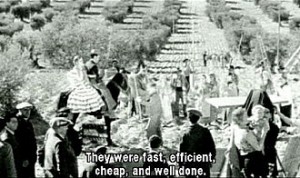

We begged some footage of anthropologists piecing together dinosaur bones from a Mexican excavation. Overlaid a voice-over which changed their direction. What if these pictures of our past were all fiction? What if these guys were just building things they wanted to make? The voice-over concludes: “What we are watching then is not the past as it used to be, but the past as it is, an image of memory itself.” In other words, their recollection urges them to build monsters, because the past of this country is filled with a terror that we identify throughout the film as western imperialism. A history of invasion. This theme returns in the television sequence where I copped a number of B-movie scenes: The Incredible Shrinking Man , Godzilla , stuff like that. While we watch dinosaurs pace the street the voice talks about how these images were made in Toronto at the time of the Cold War when North America feared communism, free love and universal health care. These monsters the manifest fears of a post-war population. But now these creatures walk the streets again, here in Mexico—so what is it this country is so afraid of? The answer the film insistently provides is Toronto, emblem here of the impending free trade deal.

D: Even though we seem to have covered quite a bit of territory around the work that you’ve produced in the last couple of years, I still have a sense that this is only a fragment, and that there is still more to come. That this interview catches, (and then only catches glimpses) you midstream.

M: Yeah. I’ve just finished two new films. One’s a short, pixillated surrealist take on love I made with a couple of friends in Seattle called One Plus One (Boughton/Hoolboom/Ramey 3 minutes 1993). Another’s a lyric that joins a New York church with a Regina steel factory, both images of the everlasting in their own way, that’s called Indusium (10 minutes silent 1993). I’m working on a remake of Madonna’s Justify My Love. And a film with Andrew Wilson called Shiteater. I’ve just shot a multiscreen psychodrama called Frank’s Cock . I’ve shot two features with actors that I’m hoping to finish this year: Kanada and Valentine’s Day. I finished writing my first play and a chapter for a book on postmodern Vancouver. Trying not to think of that line from Yeats, “the best lack all conviction while the worst are filled with a passionate intensity.” At least it gets me out of bed in the morning.