Except as Monsters: An interview with Mike Hoolboom by Francis Crant (Vancouver 1992)

Francis: You’re dividing time between Toronto and Vancouver. Why did you finally decide to leave off living in Toronto full time?

Mike: It’s funny, you live in Toronto for ten years and all of a sudden you realize that the city you’re in is not the centre of the universe. So one day you leave just because you can. Do you know the story of Isa Janou? She was an Inuit woman whose brother died—only the rest of the relatives were in Orangeville so they paid for her to accompany the body from her home in the Yukon. She’d never been off the reserve before, and didn’t understand a word of English. She took the body south, attended the funeral, and received a sum of money for her efforts. She took her payment and began to do the only thing she knew how in this new world: she stepped back on the train again. She didn’t have any particular destination in mind, she just lined up at the ticket counter and motioned to the attendant that she wanted to go to the same place the last person was heading. In this way she travelled all over North America. One day her money ran out, so she settled. And she lives there still.

Francis: How’s Vancouver?

Mike: They used to call it Terminal City before the rail line stopped coming through, and if you squint hard beyond the Yuppie condos, the tanning studios and alfalfa bars, the shops specializing in perfumes, chocolates and anal hair removal, the crowded beaches and clean, graffiti-less streets, the welter of manicurists, hairstylists, dermatologists and breast enlargement clinics—you can really sense the rugged frontier out here. The utter lawlessness of the place. It’s the wild west all over again.

Francis: Is the film scene connected with the city or just another art ghetto?

Mike: There’s fewer makers and less work, and what gets finished tends to be on the long side. A lot of filmers run three, four, six years between films and because there’s no place to learn how to make the long distance look work, the mistakes show up on screen. The short film’s fallen on hard times of late, everyone figures you can’t apply for enough money from the arts council to make it worthwhile, they’re tired of getting programmed in a night of other shorts they might hate, no one will come to see just your one short film, festivals aren’t going to invite you to attend on the basis of a short, so after the pain in the ass to make it there’s no recognition or return so why bother? What’s weird is making the round of the fringe folks and finding that virtually all are unpacking feature length dramatic somethings. The degree of consensus is especially surprising considering that few filmers are talking to one another in these parts—just too many bad memories to crawl into the same small room and start it all over again. Besides the egos out here are so big there’s not room enough in a panel to fit everybody’s word balloons in.

Francis: What kind of images are worth making now?

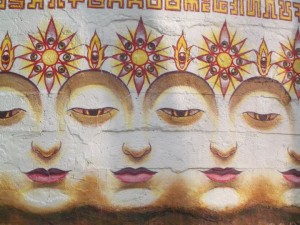

Mike: I’ve been trying to imagine a time when you would actually have to go somewhere to see an image, and having taken that walk, what that encounter must feel like. Things changed after reproduction switched from the womb to the factory, it’s hard to leave your apartment without wandering into images of every kind, and you wonder what’s the point of adding your own to a world already too full of them. I still wonder about the effect images have on our life, and am continually amazed that parents blithely expose their kids to thousands of hours of television without a clue to its result. How does an image work? And what possible place could the very marginal images I’m interested in making and viewing have?

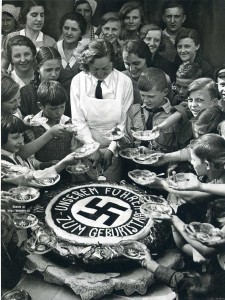

When I look at television I look at MTV because MTV is television in its purest form. MTV has essentially taken the efforts of a generation of American Bolex wankers from the sixties—rolled the works through a perfume factory, added a drum beat and beamed it across the known universe. All the moves the underground made twenty years ago are back, this time converted into advertising. Is this why I’m working, so someone can turn it into tampon commercials? Where is the possibility of opposition in all this?

Francis: What about your own work? What are you working on now?

Mike: Like everyone else I’m trying as hard as possible to sell out, I’m just not sure I’ve got the necessary smarts to do it. Because I live in mortal fear of roadblocks, the bottom of cereal boxes, back doors, assholes, endings of every kind, I try to work on a number of films at once. The most popular film I ever made was called White Museum which reverses the usual maxim that filmmakers should be seen and not heard. It’s a 32 minute film and the first half hour shows only clear leader while I talk on the track about how expensive images are, and the importance of waiting and sound versus image, etc.

So I’m thinking about doing a feature length sequel called Oedipus in Colonnus. It picks up our hero just after he’s found his wife/mother hanged and gouges out his own eyes. It’ll all be told from his point of view and of course he doesn’t see a thing, the whole film would consist of dialogue and sound effects over black leader. I’m working on an instructional surfing film for artists with Al Razutis which relates menstruation, dock worker’s strikes and virulent attacks on the ‘clean’ high art of modernism and its hidden social agendas. I’m videotaping a lecture series by Maria Lenora, the last remaining speaker of the Trewelyn language—all in original dialect. I’m working on a film with Steve Sanguedolce which is a kind of reverse adaptation of Kafka’s Metamorphosis. You remember the original where Gregor Samsa wakes up as a cockroach? In our version a cockroach wakes one up morning as a Sicilian. We have support letters from the Vatican who feel the film is an allegory of transubstantiation. We think of it as a reverse hang-over and this is what I’d really like to do: to make a film that would cure hang-overs. A useful film. A film you would want to put in your toolbox. A film you could eat if you had to. I’m interested in the notion of a mede-cine, of a kind of cinema that could be used to heal ailments.

I was speaking recently with Valerie Tereszko, a very fine filmmaker who is virtually deaf, who intends to do for sound in the cinema what Brakhage has done for the image. She says that they never play music for the deaf in school, and that this is great mistake. Because no one appreciates music like the deaf. If you ever saw her eyes fill while she’s listening to tunes you’d know just what I mean. This is the kind of music I would like to make. But I don’t know whether I’m deaf enough to hear. Inventing cinema means trying to stop thinking like a book. Some have already done this. It pains me to think that the very best filmmakers today will never look into a camera, or take up a guillotine splicer or hold a camcorder. They’ll be betting on horses, or taking baths that last a whole week just because they can, or discovering that those round Crest toothpaste dispensers, the ones with the nozzles, make wonderful dildos, or walking out of concerts where they’re nodding into two hours of stuff they never laid their ears on before and then stepping out onto the street and humming it all back in perfect time.

We’re busy constructing another world right now, a world that exists parallel to our own, in Blade Runner they called it the off-world, and we enter it every time we open a magazine, or turn on the TV or go to the movies. It’s the image world, and we recognize immediately that it’s a little more real than we are, that people are dying out there while we are stirring our coffee, standing between a grave and a difficult birth, wondering where next month’s rent is going to come from, or whether our cinema’s become a habit like all the rest. I wonder sometimes if I could just give that up for awhile, like cigarettes, like having to talk with someone and pretend we understand one another. Because they’re declaring war in the middle east. Because there isn’t a way to keep the war outside anymore, it’s in you, in all of us. Because you’ve said all you had to say and you keep talking because in the end it’s all you know how to do. Because as hard as you try you just keep saying the same thing in the same way to the same people because wherever you go the avant-garde is a small town. Because you move across the country and quit smoking and patch up with your folks and move in with her imagining this will make a difference. You are bursting with this new happiness and this new love and you want to tell everybody and all around you they are declaring war.

It’s like the story Nabokov relates in Despair. A middle aged chocolate salesman with loving wife, home, children and car ventures off on a sales trip where he spies a man who is his exact double. A dead ringer. Excitedly, he plans an elaborate murder scheme whereby he can kill his wife and his double thereby relieving himself of his dull and unwanted identity before collecting insurance money and beginning a rich new life in the south seas. The hitch? His double doesn’t look at all like him. He only thinks it does. He has a problem with the image, in recognizing himself. Did you see the last Time Magazine cover featuring their ‘men’ of the year? It showed a double-headed portrait of George Bush. The good George and the bad one. Usually they give it to one person. But now everything is splitting. We live in a country of two solitudes: on the one hand an independent cinema, and on the other American television. There’s a division here. Problems with the image. Can we stop now? The world of doubles we make for ourselves when we pick up a camera, is it any wonder some of us feel that we don’t live there? That we don’t recognize ourselves at all, as others point us out in photographs and movies? That there is something that has escaped the camera which is what we are trying to say, only we don’t have the words. Which is why the images we use are only important for what they leave out.

Francis: You’ve been working for fifteen years now making very marginal work. Why do you do it?

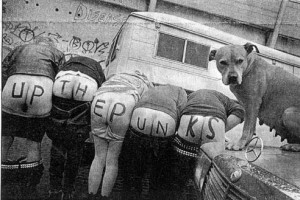

Mike: After living without for years, I finally got a TV set, and realized it’s the image of the centre, or the sticky wound which issues the flow of the centre. Broadcast’s magnetic pulse bend lives towards it, our inclinations and desires. In the face of that irresistible secretion which most of us are covering ourselves in, it is very difficult to conceive of something outside those lines of attraction. These lines are hypnotic and narrate flow, they’re about erasing history and converting the present into a stream which bears you along, and it’s hard to pull yourself out of that wake and found a different kind of imaginary. That’s where I think fringe/freak/experimental/independent work comes in. It dares to imagine, to fly, and what could be more subversive than that? Well, bombing the legislature would help, but in the meantime…

There’s a whole bunch of folks like myself who have continued to make movies our own way, with little heed to markets, it just comes out of a different place. Most of us were raised on a diet of American movies which insist that images be seen everywhere at once, by everybody, though that’s never an attitude we’ve subscribed to. If American movies are broadcast then ours are narrow-cast, inclined always towards a portion of folks who, for very personal reasons of their own, are looking for something else, something different. Because somehow those images, and the attitudes they represent, aren’t working anymore. American movies are like a hose, they spray everything. I water small plants.