Arshad: What inspired you to go into writing and then filmmaking?

Mike: I was always supposed to be a writer, but then I made a wrong turn. Filmmaking was a place I didn’t belong, and I arrived without any useful talents or inclinations. It was a world filled with men who could fix things, who could touch the world with their hands and make it sing again. Deep machinery interface. Not to mention expensive. But it promised an escape from a life I never had, and this proved too seductive to refuse. For many years I watched while my comrades produced one shining masterpiece after another while I flailed around in the dark, making small, unintelligible murmurs. But I had this great advantage: I never expected to get anywhere. So I kept throwing myself into it, and eventually, many many years later, the work improved.

Arshad: You make very personal films and you keep adding to them. How do you maintain that commitment to your work?

Mike: I recently attended the premiere of a lovely movie where the director shared with us the story of how many years and hopes had gone into the film’s making. It’s all for this moment, he announced, as the light summary of all that work was about to be unwrapped for the first time. But for this one, happiness arrives in making. I have tried to reduce the aspects of movie making that do not give me pleasure as much as possible: which for me means chasing after money, organizing other people, making appointments. What I love is the cutting room, now shrunk to the size of my computer. It is an endlessly renewable resource of cheer. How often I’ve wished I didn’t prefer it to the company of friends and familiars.

Arshad: How is your personal life related to your work?

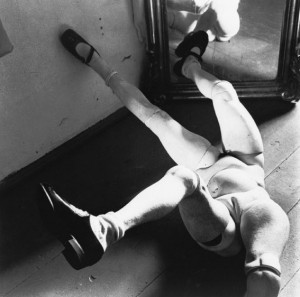

Mike: My latest movie, still undergoing renovations after an initial test drive of public screenings, is about my friend Mark, who died suddenly and unexpectedly two and a half years ago. Working with his left-behind picture archives and speaking to those who stood with him in the shadows was a way to be close with him again. Ten years ago, I began a long suite of portraits after my friend Tom Chomont called me and related a careless moment at a late night danceteria which led to his HIV seroconversion. Alongside his worsening Parkinson’s condition, I wondered how long he could hold up, trapped inside the prison house of his own body. Years after his portrait was finished, he continues to flourish, though his movements are catastrophically restricted. Nonetheless he never drops a word of complaint, or regret, or begins a sentence with the words, “If only.”

Arshad: You challenge your audience with the sexual representations in your work. Are you concerned about mainstream appeal at all?

Mike: Really? Do you think they’re challenging? There was a time I was very interested in making privates public, but everyone around me has stopped having sex, so it seems a far shore.

Mainstream appeal? I know so little about it. I don’t have a television, I listen to a couple of programs on college radio, and the music I enjoy sounds like malfunctioning heating ducts. But I would love the opportunity to direct a hockey game. (They still play hockey on TV, don’t they?) Every match is unique, why shouldn’t each be lensed in a different way?

Arshad: What do you hope to accomplish with your body of work?

Mike: At the recently finished Reel Asian Festival, director Keith Lock was asked: what are you trying to tell us? What is the moral of your film? I was surprised to hear that morals were on the menu, or that if they were, the director would be expected to know anything about them. I would like to make a movie which would make a contiguous and autonomous Palestinian state inevitable. Of course, I don’t know how to make this movie, so instead I am making home movie cryptoriums, tearing down the security walls of my apartment, working for peace amongst my friends.

Arshad: What will you be presenting at Concordia. Why did you choose those specific pieces?

Mike: I’m going to undertake an act of ventriloquism, passing along the thoughts of Swiss film festival director and philosopher king Jean Perret. He insists that there are just two kinds of memory, and two kinds of filmmakers. He whispered to me the difference between mysteries and secrets. And there are four things this professional watcher looks for whenever he sees a film. Then I’ll show André, a ten minute biographical fragment that is part of my next project, a feature length look (in six parts) at artists who died young.

Tomorrow I hope to finish recutting the portrait of my friend Tom, “finished” seven years ago. It has won prizes and traveled the world, even shown on Arte. But after tomorrow it will be shorter, tighter and sexier than ever. A deluge of pictures. I’d like to premiere this new/old movie at Concordia.

Arshad: You inspire a lot of young people. At the FNC there was a work by a young filmmaker that was dedicated to you. How does that make you feel?

Mike: It is hard to describe the feeling of relief that arrives when I see a well-considered, experimentalist media moment from someone who can still fit all their candles on a single cake. Please, before it’s too late, bring on the young! Take our screening spaces, our galleries, our cameras, but come quickly. I am haunted by the prospect of the usual graying suspects huddled beneath yet another screening of difficult movies. What we need now, more than ever, is an infusion of fearless new energies and uncoverings. And don’t worry about opening the door, or having it close behind you. Let me share with you a well-known secret: in the world of the fringe, there are no doors.

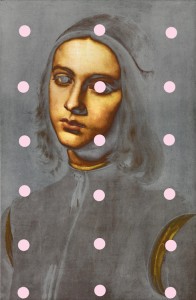

Arshad: What gave you the idea of ripping images and music and appropriating them for your art practice?

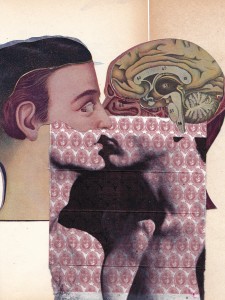

Mike: Picture theft used to be the exclusive preserve of forgers or empire states looting vanquished territories. But today everyone is busy downloading music, lectures, movies. This is all perfectly illegal, and perfectly necessary. The “interbeing” of digital media is part of its nature, digital gravity leads one to steal again and again in a weightless accumulation.

Tweets, downloading and Facebook may all be expressions of a new form of digital subjectivity: everyone can see who I am all the time. What is being left behind is the old picture of ourselves, which might have looked very much like a book: a finite self, and one which opens and closes. A self with secrets revealed over time. The dark continent of the unconscious, for instance. The digital self, on the other hand, privileges simultaneity, its dominant picture shows itself as a web where everything is available instantly and at the same time.

As someone who is interested in portraiture, I have been inevitably drawn to the stunning technological experiment we are now undertaking. It may be hard to imagine, but only a few decades ago there were no personal computers. None. Today there is hardly an office or home that is imaginable without one. This is not only changing what we do, but who we are.

Arshad: How do you feel about image ownership laws or other intellectual property restrictions? Does it ever discourage you?

Mike: Copyright laws are excellent for corporations, but less than optimal for individuals. At this fall’s Nouveau Cinema Fest I was privileged to catch a talk by Rick Prelinger, the justly celebrated American archivist who has uploaded more than 4,000 movies and made them available for public use. This is a gesture towards a digital commons. Imagine YouTube filled not only with sentimental pop effluvia and personal messagings, but network archives of the “secret” war in Cambodia (which led to the Pol Pot government and ensuing massacres), or the thousands of photographs of prisoner torture at Guantanamo Bay which have been ordered released by federal courts, but which are being withheld for the usual reasons. We need these pictures, they belong to us, and not to corporations or to governments. We need them to understand who we are, and what the government is doing in our name.

Arshad: Your work is uncompromising in its support for justice and human dignity. With all the wars being waged and humanity at an all time low, how do you keep going? What motivates you?

Mike: Humanity has always been at an all time low. What is the stat I recently grazed? That someone dies of hunger every 3.6 seconds. How many have already died in the time it’s taken to read this interview? We are in the midst of a global hunger catastrophe which is estimated to reach one billion people. Can you imagine a billion people hungry? I know I can’t. And yet in the midst of this debacle there are small moments of kindness, somewhere someone is opening a door, or visiting a friend in a hospital, or babysitting, or writing a letter asking our Prime Minister to stop the war in Afghanistan.

Arshad: Would you like to tell our readers about your personal struggle with HIV/AIDS and the struggle with friends and family? It has had a tremendous effect on your work. How do you feel about its reception? What changes would you like to see in the support system for HIV/AIDS affected individuals?

Mike: Recently, not one but two friends confessed to wanting to have unprotected sex with me, and become infected. The fantasy was not simply bareback and the thrill ride of risk, but the infection itself. How close can I get to you before the wound begins?

It feels an indulgence to speak about my personal struggle when 25 million have already died of AIDS, and so many because they weren’t fortunate enough to have been born here in Canada. What I continue to be amazed by is the sexual desert of so many couples, and on the other hand, the epidemic of unsafe sex. As if the contagion wasn’t happening here, not on my street, not in my bed, never. People under 25 account for more than half of all new HIV infections. How busy we are snatching defeat from the jaws of victory. A little latex between friends, is it too much to imagine?