The Pleasures of Waiting: Jean Perret and Mike Hoolboom in Jihlava

(Jihlava International Documentary Film Festival, October 30, 2009)

Before the beginning

Mike: Every introduction hopes to offer its audience an approach. How can we find our way towards this impossible subject, this new face? It is a problem that occurs often in the cinema, where we are so often introduced to strangers. Before they arrive some preparations need to be made, the welcome mat laid out, the table set. What is needed most of all in order to make an approach, is time, so that when they finally arrive we are all living in the same time.

This necessary time of waiting, this time out, happens very rarely on television, where new faces appear onscreen instantly. And are instantly replaceable. But in the cinema there is often a kind of pre-story, a waiting room if you like, before their face appears, before the curtains of the story part so we can meet them at last. Dearly beloved we are gathered here today. Jean Perret is a friend I have learned to wait for, and I hope you will wait for him with me. Before he comes to speak with us, I would like to tell you a story about waiting. What I am hoping to do, in telling this story, is to conjure this waiting room again, a room which will create a time which we’ll all have in common, so that when Jean speaks, we might be able to hear him. You could think of it this way: we’re going to synchronize our watches.

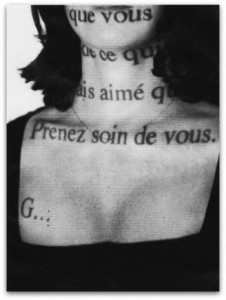

Sophie

Let’s begin with a woman. Her name is Sophie Calle, a famous French artist, but one who is determined not to let her large name keep her from the wound of living. Of taking the next step. She’s in America for a show, a talk, a lecture, a meet and greet. In the art world they call it, in a moment of irony perhaps, an opening, although if you’ve ever been to one, you know that there’s very little opening at an opening. But because of her determination, because of her uncanny ability to shed her name and walk right past it, she meets a tall, handsome American stranger. I can’t remember his name, let’s call him Greg Shephard. Greg tells her things she’s been waiting a long time to hear, and maybe they have a night and then the night after that, and then she has to go. It’s time to go home. But not before wringing out this promise from him, that he would come to see her in Paris, on a spring afternoon in May. So she gathers up her entourage of personality accessories, and steps on the plane and disappears. How many months later she waited for him in Orly, looking out over the same pier that Chris Marker’s alter ego — the one who lived only for the future — was murdered in, not once but twice. Time travelers carry their own double-dealing wounds. She waited all day but there was no sign of her American lover, so she went home, looking for some way to hold off the disappointment.

Waiting. I am waiting for him to come and talk with us. And while waiting, I’d like to share with you this story. Like all stories, it takes the place of something, or someone, that is missing. Isn’t every story, a story of waiting? And isn’t every story of waiting, already your story? The one you keep telling yourself, no matter how often you try to stop.

Love

It’s a year later, yes, exactly one year later, on the same afternoon in May, and there he is, our American cowboy, arrived at last at the Orly airport in Paris. Where is she, he wonders? Why isn’t she here? He writes her a postcard from the airport, then catches the next plane back. Now this is important to remember. He doesn’t send the postcard to any ordinary destination. Instead, it goes to the maestro of romantic obsession, the French artist Sophie Calle. When she receives the card, and realizes that he has indeed kept his promise, and his appointment, exactly one year later, she comes to a sudden realization. This is the man I have to marry. I will go to America, I will step into his not-quite-functioning, larger-than-life automobile. Together we will go to Las Vegas, and I will become his bride, never having to leave his car. American style. This is the man I need to spend the rest of my nights with.

How does one begin to speak about waiting, its necessity, the particular joys that waiting makes possible? How to step over our usual responses (like boredom, or irritation) in order to sit fully in the present moment of our waiting? Or to put it another way: how does waiting make love possible?

Master of Waiting

I would like to introduce you at last to someone who is a master of waiting. He worked for many years on radio, asking questions that were smarter than the answers. Perhaps you’ve caught up with him in a more recent incarnation, as the director of the Swiss documentary festival in Nyon. And watched him make introductions more memorable than the films he longs to wait for. He grants words to the invisible place between pictures, before pictures, before the moment of falling in love. How could we possibly wait a year, from one May afternoon to the next, in order to uncover the rest of our lives? In order to find a way out of our usual habits which are always keeping us from falling in love, over and over. Jean’s words belong in this place, in this year of waiting, which he converts into a rare and perfect pleasure. How much I enjoy the period of waiting for movies to begin, or best of all, when Jean stands before the movie and speaks. In the movie theatre, Jean grants us this moment of pause, this moment at the threshold, before the beginning. He lets us walk into it, and stand for an instant before the cascade of pictures begins again.

Experimental Filmmaker

Three years, four years, five years ago, I began to ask him questions with a tape recorder, and out of those recordings came a small book, offered for free on the internet, called Touching Pictures. Tonight’s conversation is an extension of that gesture, that talk between friends. Friends who have the time to wait. To wait to talk.

When I met Jean, in the living room of Peter Mettler, I was what they used to call an experimental filmmaker. I was interested in film emulsion and materials, with duration and the theatrical setting, and with dying of course, and AIDS, and therefore love and death and memory. But when Jean met my work he saw some wayward growth of the documentary, some mutant fungus, and I have thought of my work this way ever since.

Like any artist he offered me a picture and I stepped into it. I am grateful to him for that, for allowing me a way out of my own dead aims and ends. How small the avant-garde feels for me today, how very traditional it has turned out to be, just another genre like the rest. I can see, from my vantage of a few longer-than-necessary decades, the very young and very old remaking someone else’s greatest hits. But in the untelevised documentary there is a chance to rub together these two traditions: the first, the avant-garde, which is concerned with the signifier, with how meaning is made, the building blocks, the materials, the thing itself. And then there is the other world, in which I am a stranger and latecomer, the world of the documentary, where cameras are pointed out at someone else, striving forever to find the correct distance. Each documentary movie is haunted by this question, which is also a question of friendship: how close should I be? How far away should I be? Jean, could you come up here and join me?

The Evidence

Jean: Before I say a few words, I think we should look at the movie you’ve been working on about your friend. You’ve named it after him, Mark. Let’s see the evidence.

(The first ten minutes of Mark (70 minutes 2009) is screened.)

Two Kinds of Memory

Mike: Could you remind us again about the two kinds of memory?

Jean: One important distinction in French is between souvenirs and mémoires. The souvenir is the very near recollection of what you’ve lived, seen or experienced. The souvenir is already a story. Mémoires, on the other hand, are unreconstructed elements made of rough cuts; a pre-story. In psychoanalysis, you try to retrieve from your unconscious, elements which arrive in very rough shapes. To speak of memory is to speak in fragments, and it’s interesting for cinema to look for these rough elements of memory, rather than souvenirs. To gather rough scenes of what has been experienced, rather than pre-digested tales. That’s the difference between television and cinema. Television is at the level of souvenirs while mémoires belong to the cinema.

Memory is a non-organized story, an ensemble of rough shapes. Your movie is also made out of rough fragments and step by step you are going to try to find ways to go through your mourning process. The souvenir is a finished story, but memory is something else. Memory is not directly submitted to censorship.

Rough Fragments

Memory is related to the unconscious levels of our mind, and I’m afraid to say it, but this way of making films is very rare in film schools around the world. Why? Because we see so many films made by students who have no idea about this kind of work on memory. Because of these rough fragments, which are part of the memory of your friend, you know how much you have to pay attention to each fragment, each little part. That’s the second thing making up my pleasure. I can see how well done it is, how carefully articulated each part is. Rough fragments arrive in your desire to tell this story, and then each fragment becomes part of a very complex ensemble.

Mike: What are the rewards of chasing after the mémoire? Aren’t they likely to be moments which confuse an audience, or alienate and threaten, filling strangers with repulsion and disgust? “I don’t want to see that, I don’t want to hear that, I don’t want to experience any more of… that.” And even if they can be excavated, and at last tucked into a work which has structure and coherence, isn’t this a way of exerting mastery, of exercising further control over the wild and untamed parts of our lives, and of the lives of others? Is there any real way to present the mémoire without showing it like an animal in a cage?

Voice

Jean: Yes and no. As a filmmaker you have the freshness to discover and pay attention to each single fragment. Each picture fragment has the chance to be alive in the composition of the film. So you will face each moment, each image you shot or found. I don’t think your film will be too gentle with its pictures, or with us as spectators. And, of course, you are manipulating us. The filmmaker is manipulating the spectator. It’s your voice. Your voice is not a rough one. Your voice is a kind of song. Your voice, for me, is always related to emotion, this tenderness of your voice. You’re completely excited, sometimes nervous and upset, in your editing, but on the other hand, your voice is giving another way to breathe, another way to reflect what you’re doing.

The Whole Story

So you have these two different levels of expression: a visual one and your voice. Your voice is not a commentary, not a voice-over coming from the top of the sky to explain the pictures. It’s interwoven with the pictures. The voice, of course, has to be yours. It couldn’t belong to someone else, that would be impossible for me. This voice arrives out of your experience and understandings. We will never know all of these passages. Your voice is coming through your body and soul and out of your mouth to the microphone and onto the film. In the end, your voice carries the density of what your life is, and this density is mysterious, we’ll never know all of it, just like you’ll never know all of the life of your friend. You’ll never even know everything about your particular relationship, or the love you shared, or why he’s so important to you, this invisible man. We can’t know everything. That’s why we’re always in the process of memory. Memory isn’t the whole picture, or the whole story, it offers only fragments, and you’re really in this process with your work.

You trust us as spectators. You believe that we can get through these stories.

Mise-en-abyme

Why should we be interested in this guy? This strange guy. But we are completely fascinated by him, or if not by him, then but by the way you approach him. You know how to put — in many fragments of your film — the whole story of the film. In the beginning we are under water, and then we surface and arrive in a boat, and that is the whole story of the film. You are trying to be in the life of your friend, in the water of his life, in the water of your emotions after his death. And on the other hand, you have to be outside, you have to keep a distance, you need a point of view to tell these stories. You’re in and out at the same time, and this, of course, is the beginning of the story.

You’re a very intellectual filmmaker, you recount sensitive moments, and at the same time you make a comment on how you’re doing it. Mise-en-abyme. It’s part of your talent to make this metaphor at the beginning, to be inside the intimate circle of this dead person, but also to be outside as a filmmaker, like a dictator, in order to tell the stories you’re interested in.

Our Time Apart

Mike: Jean and I haven’t seen each other for nearly a year. When we met I wanted to ask at once: what’s happening in your life? How is your festival and your parents? These questions point to our unshared past and time apart. Won’t you please summon up these moments and tell me about them? I’m asking for a summary, for an orderly recounting which typically takes shape as a story, in other words, another souvenir. Our ability to speak our own past, to convert our experience into accountings, seems fundamental to our intimacy and shared understandings. And yet you insist again and again that we should lean into the winds of the mémoire. To refuse a survey report and look instead for fragments of memory.

Too much of the documentary tradition, not to mention contemporary documentary, is taken up with this endless quest for the souvenir, where the past becomes a story, and the people in it are characters. Each character requires a trajectory with its own beginning, middle and end. But aren’t those trajectories true to life, or at least, true to the conversation we had at lunch, when we both sat recounting moments of the past year?

Closing Time

Jean: It’s strange, as you said. I don’t know how your experience is, making pictures, making films, but I worked for years in radio making interviews, speaking into the microphone. Accompanying feelings of relief or wonder was the sense that as soon as the microphone was closed, everything vanished. Everything was lost. It was given for a few minutes, but as soon as the microphone was switched off, it was over. And this led naturally to the necessity of the next rendezvous with the microphone.

You asked me over lunch what films I’ve seen. I don’t know. I see so many films that I can never tell you what are the best ones. I have a notebook that answers these kinds of questions. And if you ask me what about the Visions du Réel Festival, what happened last April? I don’t know what happened. I can recollect many fragments, but more importantly, I need to ask by way of reply: don’t you have the feeling, especially working inside this kind of collage about your friend Mark, that as much as you’re collecting and putting together, you have an equal fear of forgetting everything? What is your feeling when you’ve finished the film? This film you haven’t been able to finish for months now. You told me that yourself. You can’t leave it. You asked me to come to Toronto and sit next to you and say stop. Give it to me, I’ll show it in Nyon. So you can’t leave it, and maybe making a film and organizing a festival has this in common. You are gathering all these fragments of memory for your friend, and a festival is also a way to gather, to bring together… I like to speak of family, but it’s more about community.

Mike: Each film offers a community of pictures.

Jean: It vanishes immediately. On the last day of the festival the community disappears. And with the first screening of your film, it isn’t yours anymore. That’s why you have to make more films.

Mémoire

Mike: I’m wondering if you might elaborate on the mémoire, these pointed memory barbs. Could you give me an example from your own life, or a movie you’ve seen?

Jean: If I speak in terms of mémoire and cinema, titles or actors are not important. I’m more capable of mentioning moments that are important to me, related to the experience of my life, of my emotions and sufferings. I think that to be involved with cinema like we are is a question of our lives, it’s not simply a job. Cinema and life are completely the same process because we are looking into films for the mémoire of emotions that we have in our lives. These sequences and fragments of film are reviving and reinventing our own memories. Cinema is reinventing for me who I try to be. Who I am in my consciousness and also in my unconsciousness.

Globalization

That’s why I’m very attracted by your films. I live with your films because they are made out of these uncensored fragments, edited together to try to understand who we are in this complexity that we can never know completely. It opens windows into the complexity of the world. The complexity of the world goes against what we are living in now, the globalization of experience. Are we really the same person, sharing the same experiences, with the same values, hopes and sufferings? No, of course not, these fragments of mémoire insist that we are very different from each other. We see that in your own pictures. You never have one surface of pictures, you have many surfaces of pictures which occupy the same time.

Two Kinds of Filmmakers

There are two kinds of filmmakers. There are filmmakers who film what they know they want to show, and filmmakers who film what they don’t know. One way to film is to search, and for others it is to find. Filmmakers like you are searching. Of course you uncover ways to tell the story. But most of the time, filmmakers who film in order to find are boring, because they know in advance what they’re going to see. It’s more interesting to have filmmakers who might find something or not, where the process of searching becomes the film.

Pitch Session

Mike: If I was going to the pitch sessions here at the festival, and my movie had not begun, I would try to make this movie into a story, a souvenir. The first story that would need to be told is that my friend died at the age of thirty-five. Why is that? The question of his death and suicide would provide the bracing storytelling momentum which the souvenir requires. It was difficult to keep my memory of Mark alive against the gravity of that storytelling urge, as his friends and family kept asking: why did it happen? Did he leave a note? Were there clues or warnings? When something is missing, language rushes in to cover the gap. A gap that was particularly wounding because of the nature of his death. What drove him to suicide? To make the film as an answer to that question would reduce his life to his death. It would take the Mark that I knew, the person who sat in the dark with me for those many hours, and shrink him to the one who couldn’t go on. Here is the childhood wound, the teenage difficulty and the adult troubles that will all lead, like a royal red carpet, inevitably and inexorably, to the moment of his death.

Global Village

Mike: Doesn’t the act of storytelling, which often means filming what you already know, make the story legible for a larger public?

Jean: Not yet, because the production of audio-visual material is a catastrophe. We are speaking about the mainstream of images, and what you’re doing doesn’t belong to those traditions of storytelling. Most audiences are lost all the time, they wouldn’t be able to deal with what you show. How can they begin to understand the fragments you have found when they are committed to watching movies where everything is told in the first five minutes? Complexity is forever being reduced to a single story. There is one belief and one global village. You, on the other hand, are telling stories of little villages. You are a villager, even though you are living in Toronto. The lives you commit to film remain mysterious, and because of that, it’s an invitation for our own minds and memories to keep on working. You are opening while most films are busy closing. After five minutes they’re dead. Most television productions are dead in the first minutes.

Today’s Market

Mike: But doesn’t this searching approach risk leaving many people behind? Or perhaps it risks leaving them ahead, in the dark. In the darkness of our own lives. Is the cinema of searching and fragment retrieval only for specialists?

Jean: Our job is to try to share as widely as possible what we know and try to understand. That’s our job at the festival, as journalists or artists. The television programmers understand what the public needs at eight o’clock in the evening, at ten o’clock, at midnight. They know their audience, and this knowing becomes a program. They want to satisfy. I believe, on the contrary, that the audience should come to the work, to the films, to the poetry, to the creation. They have to make a step in your direction, it’s not only incumbent upon you to make steps towards them. But this kind of thinking doesn’t follow the rules of today’s market, not at all.

Mike: It is a commonplace nowadays to speak of documentary subjects as characters. By imposing storytelling structures, a certain person, a certain city, a certain condition, can gain definition and coherence. Oh, I see! Oh, I understand! Though of course the danger is that the gift of understanding is given too quickly. Do we really know all about it? With the souvenir there is little time for (wait here), waiting for the moment to speak, or to feel the echo of that speech, the way the wound of language, the hurt of language, continues long after the words have finished. Even here in the streets of Jihlava, where everyone stays young forever, you can see some faces that have stood inside the tsunami, the catastrophe, of language. Sometimes we need to wait, and look at a face that has listened too well, that has learned its lessons too well, that has seen too much. Sometimes we need time with these faces, only it seems that part of the storytelling enterprise, the business of the souvenir, is to pretend that time itself no longer exists. It’s always rushing to connect one event to another, rushing to the end.

Tired

Over lunch we spoke about being tired, an old theme in our conversations. Perhaps it is because I am always meeting you on the run, or at your festival, where you are busy staying up too late, watching too many movies, having too many conversations, giving too many inspired introductions. I can feel you opening yourself to this fatigue. It seems a necessary condition, and also a pleasure, perhaps the first pleasure that makes all the others possible.

Jean: Please begin with your own tiredness.

Mike: Mark’s film has contributed to a growing fatigue. Each day the computer waits, filled with his grieving, heartsick friends and family, and pictures of him when he was still alive. Returning to these sequences is like watching him die over and over again. Part of my wanting to finish the film is also a desire to lie down beside him, or at least, to rest in peace. To release the gravity of this deep exhaustion.

Method

But I have also learned something about my method in the past few years, and this has been disappointingly clarifying. I love the feeling of afterward, so my working method has been devised to be always finishing. Always Be Closing. Other makers carefully and laboriously set themselves to work, struggling over the next sentence, the next brush stroke, the next intersection of picture and sound. I like to hurry from the beginning of my movie to the end, like those almost-lovers in Godard’s Bande a Part that charge through the Louvre. History, it happens that fast. In the early days, when I made 16mm movies, I would race my guillotine splicer to the last cut, then go back to the lab and get the results printed. Nowadays, I know that I have to pause, and turn back to face the place I thought I had already been, like the famous pause of Sisyphus on top of his heap. In that pause, I am invited to return to the beginning of the movie, and dig a little deeper, and see what I didn’t want to see because I was blinded by the finishing line, or by sentimentality, or habit. And so I return to the beginning where I race headlong for the end once again. As a result, my last movie, Fascination (70 minutes 2006), was “finished” and exhibited in radically different versions. What I needed to learn about my working method is something that is rarely taught or spoken about. It is a question of not-doing, of realizing the space of waiting, or making that place palpable and visible. I need to be able to rest in that place. It is not an address or a building, and not home. It is the place between addresses, between the numbers and lines. Not the figure but the ground. I am trying to come back, again and again, to ground.

Break Up

Returning home recently from a small round of talks and screenings that provided a welcome intermission from my real life, I felt like a walking corpse. Though I went through the motions, I knew what was expected, I nodded and smiled and acted as if I was still here, merely human. Weeks passed before some small spark, or suggestion of a spark, hinted that this too might change. How very tired I have been during the many relational dramas that coincided with the film’s making, the endless door closing, the interminable break-ups. Perhaps this forbidden zone, the era of personal prohibition, has been a way of trying to shed an outmoded operating system, and at the same time reaching for a way to get high. I am remembering the dark circles that cartoon characters used to push from ceiling to floor, or up walls and doors, before they jumped into them. Each of these break-ups has been a dark hole that I have adjusted to a comfortable uncomfortability, then dove right in. And what a richness of feeling there has been. What an extravagance of emotion. The grieving and work fatigue have arrived from a kind of addiction to endings of every kind, and I’ve begun to wonder whether I could ever manage without these distracting tumults.

Exhaustion

Jean: Being tired seems a necessary pre-condition to accomplish this film and finish it. Why?

Mike: Old habits and patterns of attaching myself to my friend, or attaching pictures to him, leave me when I’m in that state. I become too tired to repeat myself. It remains my hope to invent an approach to Mark. And in order to do this, it’s necessary to be tired.

Jean: I think memory works better when you’re tired. You have less defenses. Memory can bring back fragments of what you don’t want to know or remember. Tiredness is a way to be closer to yourself. Many filmmakers are working hard, and this work leads to exhaustion. Sometimes you’re at the edge of life and death, or life and something which makes work impossible, though it has to go on. This is a very important place to be.

Your films are not meant for holidays. Holidays are made to recover, and to become less tired. I don’t believe in that at all. We have to be tired because we want to work on our memory. Tiredness is a way to be closer to who we are. Fatigue means being closer to emotions, and to memory. When you’re very tired you can’t speak properly, or make good sentences. That begins to be interesting.

Mike: When things are breaking down and the smoothness is gone.

Jean: Then memory delivers unknown fragments of myself. In your films I find again fears from my childhood. For instance, in the pictures you make underwater.

Mike: You’ve told me more than once that you’ve felt so tired, and for so many years now, that no matter how much you sleep, you’ll be exhausted until the day you die.

Jean: I can tell you something very personal. When I was a schoolboy of ten or twelve, I wrote a little piece for my teacher. It was a portrait of my mother. I wrote, “My mother is always tired.” I gave her this text and she was very angry because for her it was a deep critique. I think she was tired all her life.

I’m not so good at writing, but the best things I’ve done have been written in an overwhelming fatigue. In the moment when you have no strength anymore to write and you’re still writing. You don’t even remember what you wrote the next day, but because you’ve done it, it’s truth, and you have to keep it, even though you want to have censorship. It’s always better to write after the gym or other kinds of physical exertion.

Mystery versus Secret

Tiredness makes everything more complex. I love cinema because of its complexity. It means we will never know everything. We will never know the totality of your friend’s life. Why did he decide to die? Cinema has to do with mystery, not with secrets. A secret is made to be opened, while a mystery has to be remain unsolved. You cannot explain a mystery definitively. The images in your film gain depth because of this quality, the mystery of the main character, the mystery of your relation to him, the mystery of the film itself and this process that tries to gather fragments of memory.

Projection

Cinema is made to touch the world, but at the same time, it’s a way to maintain distance. Cinema is here and there, fort and da, like Freud said. That’s why we need projection. During a projection the viewer is in the screen, while still remaining in a seat. You’re moving from your seat to the screen and back again, and this movement is important.

Fear

Memory fragments are made to be frightening sometimes. A good memory fragment is supposed to surprise us, to ask questions, to profile doubts about what you’re doing, who you are, why you’re so tired. Why are you doing this kind of film for years now? Why, Mike Hoolboom, why? What do you fear?

Mike: That we’re at the end.

Jean: You didn’t answer.

Mike: For the last ten years I’ve been making biographies, though it wasn’t planned, one necessity followed another. Mark was my editor for all of that work, so when he died it was likely that I would continue making biographies. Though I wanted to refuse the sense that with the movie’s ending, a viewer would feel they knew everything, that they had come to the end of him. I needed to avoid the sound bite, the capsule summary. I hoped that strangers would learn to wait for him.

Mark rarely ventured into the centre of his own life. He was always the supporting cast, so his role as an editor for me was typical. How to make a picture of someone who was never in the centre of their own frame? To make a picture of someone who is always about to arrive is like articulating the pause at the end of the timeline. Or waiting for a friend. Sisyphus on his heap, about to step back down again. The movie is not done yet, but hopefully soon.

Correspondence

Jean: I continue to believe, in an old-fashioned way, in correspondence. I think images are made to speak and to write. Cinema evokes a special time during the screening and then afterwards in our memory. This special time can be an invitation to reflect and to share. I just wanted to tell all of you as filmmakers and festival directors, sales agents, producers… (TV camera crew comes into the theatre) You’re too late! These kind of people are always too late. Nice people, but too late. And most of the cinema comes too late, of course, because they think it’s easy. And it’s not easy.

Carrying on this kind of correspondence brings a fantastic pleasure because of the images we share. We can enlarge the experience of our lives. Mike, films like yours are invitations to be here, to try not to be perfect, not to be masters or efficient in a business sense, but to share a way to live in the face of dying. Correspondence: I think it’s a privilege we can share.

Is the act of finding the mémoire and finding a way to present it, to offer it a frame and a stage, somehow a political act? We are surrounded by these I-machines – these machines like I-phones and I-pods, everywhere our technology (made in faraway sweat shops by poorly paid globalized workers) is saying I I I I. The mémoire is also coming from this place of the I – so how to pry it apart from the sleepwalker of capitalism, from the drowsy teenager content to listen to corporate music, from the hip twentysomethings content to watch corporate movies, from the smartful thirtysomethings who are content to read corporate books. All of them reading corporate newspapers, and following corporate television. Could you talk about the difference between the way our capitalized, globalized culture works to produce subjectivity – and the relation between that de-politicized alienation and the I of the mémoire? How to rescue these deep sea operations from solipsism?

![sophie-calle[1]](http://mikehoolboom.com/thenewsite/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/sophie-calle1-213x300.jpg)