Amanda: At the end of your essay Fear of Flying, as you are considering the impact of the American Empire on other nations, you ask, “What part do I play?” and “What do I do next?” As a filmmaker, writer and curator here in Canada, can you comment on the relationship between American politics and Canadian exhibition and filmmaking practices? What part do you play, and what do you do next?

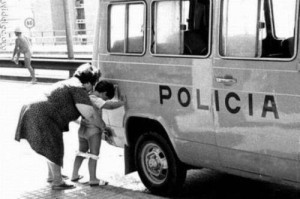

Mike: The question of politics rubs at me, every smooth moment is newly raw after Canada’s nine imperial years in Afghanistan. The daily not quite accidental civilian deaths are covered over with the usual national security blankets. And we have seen, at the recent G8/G20 summit in Toronto, how quickly the most basic civil rights may be set aside. What do these far away too close events have to do with artist’s film and video, with the question of practice for instance? Why is it that one might attend fringe movie events around the globe and find scarcely a mention of warfare of any kind, instead, the freshly minted archives are teeming with universal themes and personal exiles.

One of the ways an empire projects itself is through the pictures it creates. These can be so powerful that they refute physical, documentary evidence. This occurs each and every day in a program that insists on calling itself, without a hint of irony, the news. The news is filled with pictures, but most of these are ruling class fantasies, padded out with the scripted telltales of elected officials which we will learn, when no one cares any longer, were nearly all lies. How can we begin to create pictures that actually show something, in the fog of catastrophes that showers out of our touch screens and home computers? How can we gain some ground for our practice? How do I know what I am looking at? What is my practice? How can I use this camera to look, instead of to repeat received opinions?

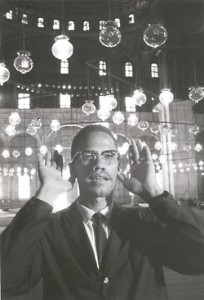

Each time we raise a camera we are creating a relationship, hoping to find a way to create pictures that will look from both sides of the camera. The foundation of this practice, it seems to me, is ethics. Isn’t it? An ethics of light. How can we learn to see the light that we are actually living in, here and now, in order to illuminate a face, for instance, a face we might have seen a hundred, a thousand times already? How to wait until the light already in that face arrives. How to live so that we have time enough to wait for that face, that light, this moment? This waiting, this suspension of time, this concern with the detail, with the small and overlooked, perhaps this is the beginning of a real politics of the image.

Amanda: You mention newscasts filled with pictures from the ruling class, and this leads me to additional questions of nationalism, borders and geographic identities. Here in Canada, much of our news comes from large media conglomerates based in the United States. Many of these pictures are based around territorial questions which form the root of so many wars and conflicts. How do we, as artists, approach these ideas of borders and national identity in the face of such seemingly arbitrary lines drawn on maps? Are we to engage with these boundaries?

Mike: Whenever I fly back into Canada, I watch the so-called security people pull several people of colour aside for extra questioning. Though many were no doubt raised in families who have resided in Canada for generations, their unbleached faces mark them as foreign and therefore dangerous. It’s so disheartening. As I watch them being led away, I can’t help thinking about the internment of Canadians of Japanese descent during the Second World War. Or the head tax on the Chinese at the turn of the last century (after workers were exploited to build the national railroad, they weren’t wanted any longer). Or turning away a boatful of Indians (at gunpoint no less) after the First World War. I think the question you ask can only be posed between white people of a certain class, everyone else is busy living with borders projected onto them, night and day. When Cameron speaks of not being able to get a cab to stop for him at night because he’s black, when Susan feels the hostility of fellow travelers on the Montreal metro because she’s holding hands with her black boyfriend, these picture borders are being projected again and again. What kinds of pictures might work to further a counter-momentum? To make “white” again a colour, to create a picture arena where multi-culturalism is as normative inside the frame as outside, in jury selections, in audiences, in panel speakers?

Amanda: How do we reconcile the light that we are living in with the darkness and resulting shadows?

Mike: I have been taught to embrace virtuous feelings, good foods, fine company. These qualities are high minded, as the saying goes, as if one could live somehow above one’s own life. But instead, I am down here in the murk of this present moment, and the many negative feelings that arise do not need to be sent away or covered over, but instead patiently watched. After the death of my friend Mark, I needed to be close to him, or to what remained of him, in his friends and familiars. I began making pilgrimages to the townhouse he lived in with Mirha-Soleil Ross, epicenter of grief and catastrophe. It was there that he ended his life, and that life was busy going on. How many cats were left behind, all wondering why? I didn’t enter this darkness to solve the question of his suicide, but to try and help, to pitch in, and to sit with my feelings, no matter how unbearable or uncomfortable. And from this place, caught between the living and dead, pictures began to emerge. A face caught in the morning light, a hand reaching to the window, a cat stretching out on the front step. These pictures became a beckoning path, and that path was filled with difficult, sometimes fraught, social relations, with people who had been pushed to the very edge of their own lives because of this catastrophe. We were trying to find a way to relate to one another, even as the ground beneath us had turned to water. How easy it was to say yes to the charmed, easy grace of Mark’s manner. Death confers a temporary sainthood on nearly everyone it touches. How much more difficult it was to say yes to his shadows, particularly when they were so close to my own. In fact, to recognize them, to bring them into focus, meant living inside my own fears. This was the necessary prelude to creating a picture.

Amanda: I am also moved by the image you paint of us looking from both sides of the camera; creating pictures that are turned both inward and outward. Subject and object simultaneously observing and being observed.

Mike: The illusion, the promise in every advertisement, is that one need only raise the cellphone, the I-prosthetic, the camera, and point it in the direction of a momentary distraction and a picture will arrive. What has been banished from the digital picture is time. The assumption then, the picture behind the picture, is that there is no time in pictures, that pictures no longer take time. Though that’s not true now, and it wasn’t true a hundred years ago. I am not longing for another better time, don’t get me wrong. But the requirement that finite picture rolls would be loaded into cameras, and that they would need to be “developed,” after the moment of encounter, is itself a picture of the time that exists, or doesn’t exist, in each picture. Without this time one can create a “shadow practice” of picture making. With the aid of the souped-up, mega-pixelled image bazookas already available, it’s possible to create jewel-like mirages. But the most important qualities of a picture, I think, lie outside the intention of either party, before and behind the camera. There is something else coming into focus that can’t be found in a viewfinder, and sometimes it can’t be seen until years later.

Amanda: This “something else” that comes into focus, is it something fixed or mutable? Even when it does come into focus (perhaps years later), will it be evident to all viewers, or is it even possible for one viewer to grasp its entirety? Your description makes me think that each viewer might receive differing impressions of the same shared experience.

Mike: I approach each moment with my history of attention. My learned responses are already in place, and what I am hoping for, particularly in the second childhood of the cinema, is to undo some of these knots, to rework my tried and truisms, and be led (effortlessly, as if I were weightless, and without a past, as if I had never seen anything before) into some new geometry of desire. But in the meantime, every book I pick up, every conversation I have, arrives with some words that appear very large and loud and underlined, and others that can’t be heard at all. When the most unhappy person in the city, announces, “I love you,” I can hear them loud and clear, but when the brightest, most altogether one shines out from a smile that never ends and utters the same words it’s as if they’re tapping out code from an unmet civilization. We each have our likes and dislikes, our favourite breakfasts, what we have come to learn as our tastes. Each of these inclinations provides a frame around experience, a cut in other words, and what is being cut out is nearly everything. The element in a picture, or a simple phrase, which might return to me years later, is some of what has been left out, or left behind. “It” can come into focus in the middle of a dance shuffle, as the body moves into a philosophical position more readily able to receive some left behind impression, something which can’t be faced up to yet. Some pictures, even pictures which we actively dislike, carry this siren call, though the ears to hear this tune might not be fully formed for years to come. When it finally arrives, this song can carry us back to some moment of ourselves that we wanted to permanently shelve, some terrifying romantic dysfunction, some bad family break that might appear for a moment flexible after all, and ourselves no longer crouched underneath our cherished place of victim, but newly emboldened, able to step back into the dreaded room with an even feeling and steady breath, ready to face up to the old monsters. Is this a unique and singular feeling for each of us? Maybe, though even as we are all busy cutting out parts of our experience, we are also summoned, each in our own way, to close the circle, to move towards exactly what cannot be seen or spoken.

David Foster Wallace might put it this way: “Huh. Well you and I just disagree. Maybe the world just feels differently to us. This is all going back to something that isn’t really clear; that avant-garde stuff is hard to read. I’m not defending it, I’m saying there’s a certain set of magical stuff that fiction can do for us. There’s maybe thirteen things, of which who even knows which ones we can talk about. But one of them has to do with the sense of capturing what the world feels like to us, in the sort of way that I think that a reader can tell, ‘Another sensibility like mine exists.’ Someone else feels this way to someone else. So that the reader feels less lonely.

…If you look at the history of painting after the development of photography – that the history of fiction represents this continuing struggle to allow fiction to continue to do that magical stuff. As the texture, as the cognitive texture, of our lives change. And it’s the avant-garde of experimental stuff that has the chance to move the stuff along. And that’s what is precious about it. And the reason why I’m angry at how shitty most of it is, and how much it ignores the reader, is that I think it’s very very very very precious. Because it’s the stuff that’s about what it feels like to live. Instead of being a relief from what it feels like to live…

What writers have is a license and also a freedom to sit, clench their fists, and make themselves excruciatingly aware of the stuff that we’re mostly aware of only on a certain level. And that if the writer does his job right, what he basically does is remind the reader of how smart the reader is. Is to wake the reader up to stuff that the reader’s been aware of all the time.” (David Foster Wallace, in Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself by David Lipsky)

David Foster Wallace: “…It seems like the distinction between good art and so-so art lies somewhere in the art’s heart’s purpose, the agenda of the consciousness behind the text. It’s got something to do with love. With having the discipline to talk out of the part of yourself that can love, instead of the part that just wants to be loved.”

Amanda: You’ve discussed the link between subject and object on both sides of the camera; where do you see the viewer and the audience fitting into all of this? I guess this brings us back to the first question: as audience members, what part do we play, and what do we do next?

Mike: The feelings that Wallace describes are about the nerve endings, the meat, in other words, they signal a return to the body, and how this is made possible through so-called avant books. Literature that stretches the form. The shape of the texts conjure an atmosphere, a longing and a mood, along with its manifest content, its plotted characterizations. Am I going to argue that people need to enter into screen culture in order to find their way back to their bodies? Or page their way through difficult literature in order to feel something? I think each moment offers an opportunity to wake up or to fall further asleep. I used to feel that this could only happen watching fringe movies, but now I am not so sure. Perhaps this factoid could be entered into Ripley’s Believe it Not Museum in New Orleans, or perhaps that truth has also been washed away. Difficult movies need to be engaged and thought with and seen through and struggled with and amused against, otherwise they are inert and faraway and don’t “work.” They require work on the part of the spectator, real engagement. This means waking up to this moment of light and sound. Or not. This waking up is a picture of how an entire life might be undertaken. Or again not. Engaged no matter what the necessary level of difficulty.

What is the next step? Knowing how to turn the page perhaps. To take the next step, or find the next word once the lights of the theatre go up again. How can we know what our field is, and touch it with our practice? How could we say no to empire while managing to take the hectoring voice inside and make that a little softer? To say yes when we really need to say yes, and open the door, and admit everything, and to say no when we need to refuse and draw a line. I think this is the practice: to be soft and hard. To know your field and touch it with all your soft and hardness. In order to do the work of this moment.