- Mark Scala (pdf)

Mike Hoolboom: Imitations of Life

Feb. 13–June 7, 2009

Gordon Contemporary Artists Project Gallery

Works are created by works, texts are created by texts, all together they speak to each other independently of the intention of their authors.

– Italo Calvino

What matter who’s speaking, someone said, what matter who’s speaking?

— Samuel Beckett

Self-described fringe filmmaker Mike Hoolboom has gained critical acclaim on the international art-film circuit for works that poetically explore themes of desire, memory, and history as they are found embedded within the medium of film. 1 In creating, dissecting, and reconstructing films, he treats them as discrete containers of time, pictures, and sounds, offering texts that helped shape the feelings and thought processes of people in the twentieth century the way literature had previously done. Hoolboom strives to give new meanings to this visual language, not by adding to it, but by mixing and recycling things already filmed. The patent artifice that goes into constructing these montages reminds the viewer that films are not really about life, but about its imitation in a medium that is often mistaken for reality because it perpetuates so many of the same illusions. 2

Hoolboom has been absorbed in mastering the language of film since he was a teenager growing up in a suburb of Toronto, where he began making movies with his father’s Super 8 camera. Hooked on the medium, he went on to study filmmaking at Ontario’s Sheridan College. At the same time other students were learning commercial techniques, he gravitated toward alternate expressions, experimenting with hand processing and the manipulation of light, sound, and time to undermine the narrative continuity sought by mainstream filmmakers. 3

While still in school, Hoolboom developed close friendships with other budding filmmakers interested in pushing the boundaries of the medium. He was a co-founder of Pleasure Dome, a film and video group that created a vibrant underground film community in Toronto during the 1980s and 1990s by sponsoring film festivals and late night showings in the city. Hoolboom’s works, which include more than fifty videos and films, have been shown in more than three hundred film festivals worldwide. Twice, in 1993 and 1996, he received the award for best Canadian short film at the Toronto International Film Festival.

Yet it is unlikely that we will see Hoolboom’s films at our neighborhood theaters. His haunting meditations on subjects ranging from deathbed memories to themes of homosexuality, AIDS, and mass psychosis offer no happy endings. Instead, Hoolboom’s films speak of the vulnerability of life and the jagged continuity of love in the face of society’s destructive forces. Evoking the revelatory juxtapositions found in memory and dreams, they fight the numbness ensuing from what Hoolboom terms the “colonization of the imagination,” the way mainstream movies have constrained us into thinking there can be a single, lucid master narrative—one with a beginning and an end. 4

Hoolboom’s ten-part Imitations of Life (2003) is an elegy for the twentieth century and its memory, history, mass psychoses, and delusional visions for the future, all as they are revealed through films spanning the breadth of the medium’s history. 5 Combining his own footage with segments excised from the vast body of existing films—scientific, documentary, musical, classic, or science fiction—Hoolboom has composed a meta-narrative in which film is the raw material unfolding the dreams and nightmares of those memorable times.

The footage Hoolboom uses no longer has its original soundtrack. Instead, it is accompanied by voices—narrators or commentators whose memories and ruminations on humanity’s dark impulses stand in counterpoint to the original intent of the filmmakers, who may have only sought to entertain or instruct, but who have inadvertently captured something disturbing about the human soul. The unmoored commentary, whether seen in captions or inter-titles, or heard in the spoken word, reveals pictures as windows onto secret truths. 6

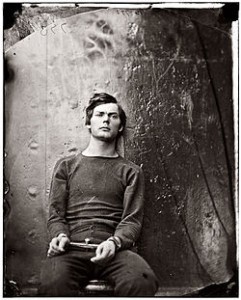

With its cannibalization of individual film frames, Imitations of Life demonstrates the connection of old films to photography. In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes comments on the power of a photograph to transcend the sense of time. He writes of seeing a photograph of the would-be assassin Lewis Payne, made in 1865 on the eve of Payne’s hanging. “He is going to die,” observes Barthes:

… this will be and this has been; I observe with horror an anterior future of which death is the stake. By giving me the absolute past of the pose, the photograph tells me death in the future. What points me, pricks me, is the discovery of this equivalence. In front of the photograph of my mother as a child, I tell myself: she is going to die. I shudder … over a catastrophe that has already occurred. Whether or not the subject is already dead, every photograph is this catastrophe. 7

Films can trigger similar shudders of loss and mourning. Home movies of young children may elicit pangs of recognition of what was or will be lost as the child outgrows his image, becomes adult, and eventually dies. Reconstituting the ghosts of the past whose actions or beliefs have shaped the present, Hoolboom uses movies as expressions of wish fulfillment for a culture that was never careful about what it wished for, and often regretted it when its secret desires materialized as Frankensteinian monsters.

The three segments of Imitations of Life on view in this exhibition include Portrait, an invented narrative that uses footage from the pioneer moviemakers the Lumiere Brothers. The segment is a meditation on the use of film during its not-so-innocent childhood as an instrument of colonization and control, a prophecy of things to come in the twentieth century. A faux documentary of the fictional Henri le Blanc, whose goal was to establish a “democracy of pictures” by filming every face on the planet, Portrait follows him as he points his camera at people throughout Paris, a locale he eventually exhausts, which motivates him to travel to more exotic places.

Ending up in Africa, le Blanc films two European women in long white dresses tossing breadcrumbs to a swarm of starving children; it is as if the women were feeding hungry ducks. This (says the unseen narrator) was the last roll of film le Blanc would shoot. He had come to the ends of the earth and realized that the only face he could truly capture was his own. His is the face of a colonizer rather than democratizer, whose depictions of people as little more than animals is an insidious means of maintaining fictions of racial superiority. About the consequence, Hoolboom remarks: “The seeds of globalized pictures are already here, in the gesture, which converts class warfare into choreography.” 8

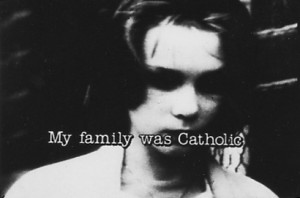

The second part of Imitations of Life in the exhibition is In My Car, filmed in a city suggestive of modern-day Toronto. The segment’s hero is a young boy from a large, dysfunctional Catholic family with too many children; because there is no room for him at home, he is sent off to live in the family car. The story comes to a climax after the boy drives to McDonalds, where he is challenged to a street race by the devil who gains speed and power by absorbing the boy’s intense emotions. Only when remembering his older brother’s death in a fiery car accident, and being overcome by the need to mourn, is the boy able to conquer the devil, whose demise rewards his emotional salvation. But there is no happy ending. For all his evil and deceit, the devil envisioned by Hoolboom has a purpose as an animating force within, whose death is a “tragedy for the imagination,” a belief to which anyone who has sought to give creative form to the conditions and motivations of human darkness might ascribe—where would the imagery of the Church be without it?

The longest of the ten chapters, also titled Imitations of Life, contemplates the passage of humanity from conception (shown in microscopic imagery of egg, sperm, and fetus) through stages of social disruption, technological advances, war, mass psychoses, and new artificial life. As the film unfolds, it moves from memory and history toward a dénouement in which science fiction is considered as the repository of our collective aspirations and hopes, embodying what we may become. Hoolboom writes, “The fact that so much of the genre is dedicated to the end of the world asks if we are moving toward life or death.” 9

Science fiction in books and movies has often addressed the socio-political problems of the present by projecting them into the future. In the 1950s, Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles and Neil Shute’s On the Beach captured the feelings of dread inaugurated by the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As nuclear fears became less intense during the 1960s, the clash between humanity and intelligent technology that was explored in films such as Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) came to symbolize the division between the dominant culture—its industry, technological invention, and emphasis on conformity—and the counterculture, which stressed mysticism, individualism, and humanistic values. 10

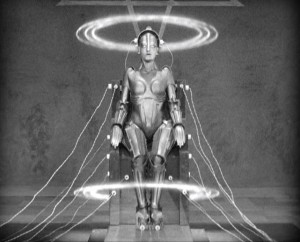

A much earlier example of science fiction, Fritz Lang’s film Metropolis (1927), has a revealing cameo in Imitations of Life. A cautionary tale about the dangerous intersection of politics, economics, and personal desire, Metropolis shows exploited workers in the year 2026 whose rebellion results in a convulsive societal calamity that signifies the inherent destructiveness of pure capitalism. While Metropolis itself is a caricature of complex social relations, Hoolboom finds in it and other examples of science fiction contemporary pertinence:

Over and over we are shown, in these glimpses of the shape of things to come, the cruelty of spectacle; mutant science and atomic anxieties, all prelude to The End. This final curtain is linked to globalization…, a centralization of industrial power and industrial pictures, mass produced and widely distributed. The world bank and the world image bank work towards the same end. 11

Other footage in Imitations of Life shows the seductive aesthetics of Nazi propaganda, as well as extraordinary nighttime views of the 1942 battle of El Alamein, marked not by death and destruction, but by flashes of cannon fire—the battle as an exchange of light. The battle scenes are followed by footage of a torchlight parade, in which tens of thousands march through nighttime streets, evoking the mob going after Dracula as well as the German population unleashed on Kristallnacht, the night of destruction that inaugurated the systematic policy of eradicating Jews. For Hoolboom, light is not a positive sign of awakened consciousness, but is an agent of control and a trigger of mass hypnosis, the most potent vehicles of which today are the screens of movies, televisions, and computers. 12

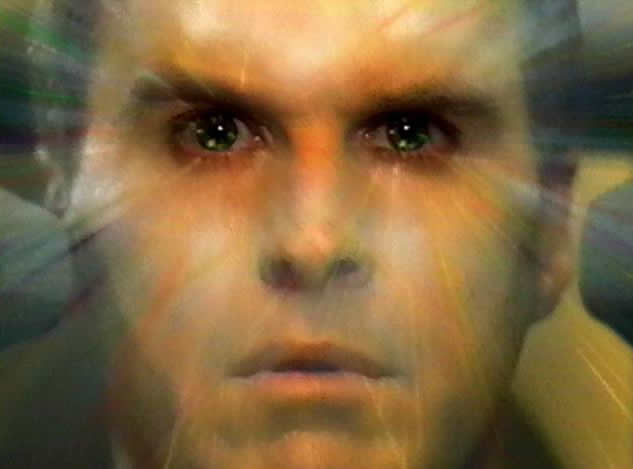

Intertwined throughout these fragments are representations of the human body, which Hoolboom—and the filmmakers whose works he scavenged—imagine as being impermanent, disintegrated, or in a material state of flux. The narrator says: “ In the future each moment will be photographed, doubled. Our bodies will grow transparent. We will enter each other like walking through a door, until at last we come to an end of the picture world, a world where we are also pictures.” 13 Common motifs in science fiction, depictions of bodies going from solid to gas or flesh to metal, are metaphors for the transformation from a physical to a mental state, or from human feeling to the emotionlessness of a robot.

The ephemerality of the body has particular resonance in Hoolboom’s life; he was diagnosed with AIDS in 1989, and has since lived with the ebbs and flows of the disease while watching many friends suffer and die. “AIDS,” he says, “changed the place I look out from, shifted it just a little, so that I could see people dying, even as they were standing there talking to me. I could see the small time we had left before the end, the quick bloom and hope before lying down for the last time.” 14

This terrible vision, when memories of the past and knowledge of the future come together, provides the undercurrent of Imitations of Life . When the artist speculates about the individual body as a metaphor for the world’s body, he sends tremors of doubt, not about the future or the past, but the tenuous here and now that stands outside the filmic myth of the culture.

Mark Scala

Chief Curator

Notes

1. According to Hoolboom, “Fringe films are the underground, the road not taken, the refused. If we could imagine cinema as the spectrum of light then the fringe are those parts of the spectrum which are unseen, like x-rays or ultra violet light.” From Tibor and Noémi, “Imitations of Life: an interview with Mike Hoolboom,” http://www.nimk.nl/en/nieuws, November 28, 2005.

2. Hoolboom reminds us “there is no motion in a motion picture. Film is comprised of individual photographs chained together, and cranked quickly through a projector producing the illusion of movement.” From his autobiography Plague Years: A Life in Underground Movies (Toronto: YYZ Books, 1998), 83.

3. These early efforts could be quite playful; White Museum (1986), consisted of thirty-two minutes of a blank screen with audio consisting of the noises of the world—TV ads, music, and a voice-over that talks with humor about how much it would cost to actually be able to show pictures in a film. The film ends with a few minutes of an image of the sun showing through the trees, an anticlimax worth waiting for.

4. Tibor and Noémi.

5 . Imitations of Life’s ten parts include: In the Future (3:00), Jack (15:00), Last Thoughts (7:00), Portrait (4:00), Secret (2:00), In My Car (5:00), The Game (5:30), Scaling (5:00), Imitations of Life (21:00), and Rain (3:30).

6. Note Michael Chion’s observation that this disembodied voice has frequently represented a ghost, a double, or the soul. In The Voice in

Cinema (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 136.

7. Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography , trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill & Wang, 1980), 96. Cited in Jacques Derrida, “The Deaths of Roland Barthes,” in Psyche: Inventions of the Other (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007), 291.

8. Mike Hoolboom, email to author, October 27, 2008.

9. Ibid.

10. See Paul Brians, “Nuclear Holocausts: Atomic War in Fiction,” http://www.wsu.edu/~brians/nuclear/1chap.htm.

11. Tibor and Noémi.

12. Hoolboom, conversation with author, August 7, 2008.

13. From Imitations of Life , 2003.

14. Tibor and Noémi.

For additional information, see mikehoolboom.com.

Checklist of the Exhibition

Mike Hoolboom

Imitations of Life, 2003

Video, 21:00

Courtesy of the artist

Mike Hoolboom

In My Car, 2003

Video, 5:00

Courtesy of the artist

Mike Hoolboom

Portrait, 2003

Video, 4:00

Courtesy of the artist

Mike Hoolboom: Imitations of Life

Gordon Contemporary Artists Project Gallery

February 13–June 7, 2009

Organized by the Frist Center for the Visual Arts.

© 2009 The Frist Center for the Visual Arts