- The studied art of living means living through art by Geoff Pevere (Toronto Star, November 23, 2008)

- The Steve Machine by Stuart Woods (Walrus, November 12, 2008)

- With reality askew, death made terrifyingly real by Jim Bartley (xtra, Dec. 7, 2008)

- Xtra recommends: best queer books of 2009 (xtra, Dec. 29, 2009)

- Robson Reading Series: Mike Hoolboom (UBC Grad Gazette, Oct. 2, 2008)

- Amazon Review by Kevin Killian

- The Machine by August C. Bourré (Vestige.org)

- The Steve Machine by Mike Hoolboom by Drew Halfnight (Matrix Magazine Issue 82, Spring 2009)

- The Steve Machine by Mike Hoolboom by The Pedgehog (www.smokecitystories.blogspot.ca, Friday, September 27, 2013)

The studied art of living means living through art by Geoff Pevere (Toronto Star, November 23, 2008)

Of the three human enterprises most often named as means to defy death – religion, art and sex – Mike Hoolboom’s novel The Steve Machine is most heartily concerned with the latter two. Especially art. In this beguiling, funny and smoothly articulated first novel – written by a widely celebrated Canadian experimental filmmaker who was diagnosed as HIV-positive some years ago – art is not only what gets one out of one’s deathbed in the morning. Nor is it merely the highest expression of a person’s determination to leave a trace. It’s the reason we draw breath, and proof that we did.

When Auden, a gay man with an overdeveloped capacity for irony and doom, first learns that he’s HIV-positive from a Sudbury doctor who looks “almost sad, like a fifteen-year-old doing Shakespeare,” he hops a bus for Toronto. There he seeks clock-punching employment as an insurance company drone, a way of filling what uncertain time he has left. “My temp-worker status suited both of us too well,” the narrator says of his boss. “As soon as I left the office it was as if it never happened.”

While Auden is resigned to his random and irreversible fate, his newly refigured consciousness makes him especially susceptible to the bland absurdities of the business-as-usual world around him. One morning he spots something as he returns to his apartment from a gym, a place where he practises his own form of short-spurt death defiance. “A posse of small children ran up to cars stopped at the light and pointed their fingers at the drivers and shouted, ‘Bang! You’re dead,’ and ran away laughing. I nodded as I stepped inside.”

While he doesn’t realize it at the time, this condition of sparked sensitivity makes Auden a perfect candidate for the bizarrely grand “experiment” of video artist Steve Reinke. Reinke is a real Toronto video artist – and creator of the internationally screened 100 Videos project – whom Hoolboom fictionalizes as a figure that combines Kerouac’s Dean Moriarty, a Queen St. West Andy Warhol and an affably horny angel of mercy. Steve’s thing is bringing out the voice that Auden hears in his head when he’s reading. Literally, as it were. “Every book is part of the library,” the narrator explains in his introduction, “and inside that library there is a voice already waiting for you.” When Auden finally meets the already-legendary Steve – at an orgy, of all un-Torontonian of activities – he’s astounded to realize that the voice he hears from books and the voice of Reinke are the same. Their bond is sealed in the “project.” Steve compels Auden to write everything down, and in so doing create something new – something vital and alive, a transcendent, death-defying “machine” generated by the synergy of Steve, Auden, words, trust and surrender. “All I knew for certain was that the voice I heard increasingly, inside and out, seemed to belong to Steve. Its soft reliable tones made even angry words desirable. I was learning. Becoming part of the machine.”

By now you’ve probably guessed this isn’t exactly airport reading, but the remarkable thing about Hoolboom’s own voice – much like his work as a filmmaker – is how unpretentiously graceful and served-straight-up it is. Even though one suspects there are worlds of heaving postmodern theory stored in the author’s mind, by the time it has filtered its way through his considerable narrative facility, theory becomes practice in the most practical way.

This is Steve’s favourite bar: “There was no dress code, not like at the Crypt, where it was leather only please or, worse, at Ollie’s where they didn’t wear anything at all. That was fine if you were under thirty, only nobody at Ollie’s was under thirty, which is why they drank too much.”

Ultimately, The Steve Machine is a post-AIDS love story. Fragmented, elliptical and intellectually whimsical maybe, but really about two guys who find in art and each other a way to look death straight in the kisser. This is really what the machine is saying: The art of living is living through art.

The Steve Machine by Stuart Woods (Walrus, November 12, 2008)

“The Steve Machine is a novel that toys with our notion of reality. A kind of fictionalized biography of Toronto video artist Steve Reinke, it is a faithful meditation on his art that nevertheless skews some of the key details of his life (in particular, the fictional “Steve” is here diagnosed as HIV positive, which the real-life Reinke is not). Other characters, such as a shambling orgy enthusiast (“the most undiscriminating man I’d ever met”), are also named for non-fictional counterparts, though the degree of realism is equally questionable. The living, breathing Reinke is even called on to perpetuate the ruse. “I love this book,” he enthuses in a jacket blurb, “though I prefer the original title, Steve Reinke, World’s Greatest Video Artist.”

Ostensibly, the debut novel from filmmaker and critic Mike Hoolboom (who has been living with HIV for close to two decades) is the story of how Auden, himself recently diagnosed, copes with the disease by latching onto Reinke in an intimate, mostly platonic love affair. As the two nurse each other through stages of the disease, Reinke divulges his life story in a series of elliptical anecdotes — part confessional, part portrait of the boundary-pushing artist as a young man. Auden is literally taken over by Reinke’s tale, possessed by the “grain of [his] magnificent voice,” which he compares to the subvocal tone one hears while reading. The book, meanwhile, acts as “a machine for producing this voice,” a sly nod to Reinke’s own highly conceptual work.

Toward the end of the book, Reinke eulogizes an artist who produced work of such beauty that it filled “its viewers with a perfect and individual happiness.” “[She] was the only true genius I ever met,” he says. “Unfortunately her chosen vocation was video art, which ensured that no one but her closest friends would ever understand her.” The Steve Machine possesses the same urgency. Like Reinke’s ambitious project, The Hundred Videos, it twists reality and fantasy, memory and desire, to create an intuitive hybrid in which art transcends individual identity.

With reality askew, death made terrifyingly real by Jim Bartley (xtra, Dec. 7, 2008)

Award-winning Toronto film and video artist Mike Hoolboom opens his first novel with a tube-tanned doctor delivering bad news. There was a sadness in this doctor’s face that remained a stranger to him, and it kept him young. Flashes of this kind of incisiveness recur throughout the book. Two paragraphs later Auden, our narrator, describes the weird numbness that can settle in when mortality hits us in the chops. I felt the muscles in my face as a large pack of steel balls that needed to be coaxed and herded to form basic human responses. Who of us has not been there?

Auden quickly decides that Sudbury is too small to handle his big news. The only place to really live with HIV is Toronto. He throws some clothes into a backpack and exits his basement apartment for the last time. A five block walk almost exhausts him, adding to his newly dissociative relationship with the world: I pretended to continue walking to the bus station until it was there in front of me. I impersonated a ticket purchase, a man waiting on the seat, a person who enjoyed lineups. Toronto’s Bay St terminal proves to have the same kicked-dog look of every bus depot in the world. He buys a paper, circles some apartment listings and heads to a bank of pay phones.

As he builds his new urban life Auden’s story is reliably fiction, until at a friend’s funeral he meets the object of his instant fascination: real-life video artist Steve Reinke, still in the early years of his career. Within moments Reinke has booked him for a writing project, on the surface a bio of Reinke, but actually a kind of operating manual for a machine that he had spent his life perfecting. Auden is profoundly struck by Reinke’s speaking voice, as if it has always belonged inside his head. It’s the inner voice he hears whenever he reads, now leapt into the mouth of this stranger.

These are the pre-cocktail years in Toronto. With limited treatment options Auden is losing friends to AIDS almost as quickly as he can make them. Hoolboom evokes the cascade of loss succinctly, without any sense of rehashing the iconic urban plague novels of the period. With the arrival of Reinke the story plunges into serious arty-conceptual territory, as Auden becomes a sort of acolyte-stenographer for Reinke’s recitation of his artistic past, always intimately connected to his personal life. Part of this is clearly the real life (including a swath of actual text from one of The Hundred Videos , Reinke’s first major work) but Hoolboom freely blends fact with fiction, among other things slotting Reinke into an imaginary role in the Toronto reality show The Lofters . Meanwhile, Auden’s inner voice feels to him more and more like Steve’s. I was becoming part of the machine.

The climax that Hoolboom has been fitfully tugging us toward comes in the hours and days after a second test result. Here his artful dodges give way to stark honesty. We’re dropped casually, but with rivetting effect, into the emotional labyrinths of our varied inner responses to AIDS. In tight snatches of groping, painfully real dialogue, almost no twist of mind and gut is left untouched. Fear, confusion, shame, regret, tenderness, a search for hope, finally a macabre sense of irony — as if, says Auden, Steve’s habitual TV-sitcom laugh had suddenly grown teeth.

The Steve Machine is finally about taking care of our collective selves, which to Hoolboom seems mostly to be about pushing our way through the stigma of HIV and making safe sex more important than fear of rejection. Disclosure — the issue that lately seems to be twisting too many HIV discussions into impenetrable Gordian knots — is lightly passed over. Hoolboom’s message couldn’t be stronger or simpler, and is hardly new: We need to commit, for real, to looking out for each other, positive and negative, on equal terms.

Xtra recommends: best queer books of 2009 (xtra, Dec. 29, 2009)

A hallucinogenic and slightly Jesus-like video artist rescues a newly-diagnosed PWA and helps him to shed his anger and self-pity. Or does he? The title character is named for real-life video artist Steve Reinke, but the novel’s Reinke is a bizarre blur, more spirit than plot point. His uninhibited, laissez-faire attitude and sexual bravado both attract and repel the narrator. Then, about two thirds of the way through, the snake eats its own tail and the blend of gritty realism and comic absurdity comes to a pleasingly emotional conclusion.

The Machine by August C. Bourré (Vestige.org)

This book had been giving me the eye in my local store for a couple months before I broke down and bought it. The premise of the novel as reported by the back cover struck me as fifty percent intriguing and fifty percent off-putting. The intriguing: Auden, Hoolboom’s narrator/protagonist hears a voice in his head, a voice other than his own. When he moves from Sudbury to Toronto after discovering he’s HIV-positive, he meets video artist Steve Reinke, only to discover that it is Steve’s voice he hears inside his head. (Reinke, according to the notes, is a video artist out here in the real world too, though unlike his fictional counterpart, he is not HIV-positive. Some of his work is available to watch online.) Steve and Auden become… well, friends is the wrong word, I think, but they become close, anyway, and Steve helps Auden begin writing a book about Steve’s life.

The book isn’t just a book; it’s also a machine, designed to heal Auden, to change the voice inside his head, and to alter the reader in such a way that a new personality will emerge from the experience. Sounds pretty amazing, right? Steve’s video art also plays a pretty big role, though personally I think that video art is one of those things that sounds much more interesting when you read about it than it actually turns out to be when you see it.

The off-putting bits on the back are the descriptions of The Steve Machine as an AIDS fable and plague journal. Though not actually true of this book (thank God), I always feel like the author (or the publisher on their behalf) has confused themselves with a social worker, and that they’ve just been assigned my case. Note to authors: I don’t give a shit about your social agenda, unless you’re telling me an interesting story in an interesting way, with interesting characters. Even then I still won’t give a shit about your agenda, but I’ll probably like your book. Whenever I see a phrase like “AIDS fable,” it makes me worried that I’m about to read a book about Gay People. I don’t mean a book about characters who happen to be gay, because I’ll take an interesting book about gay characters over a dull one about straight characters any day of the week. A book about Gay People is one in which the characters’ homosexuality becomes their sole important characteristic, and the world of the novel has been built around that sexuality, rather than it being merely one fact among many in that world. (I won’t even get into the fact that I know it’s ridiculous of me to assume that a book with an HIV-positive male narrator means that narrator is gay, except to say that we’re talking about literature as social work, not literature as art or even literature as a reflection of reality, because we know that in either of those last cases such an assumption would be foolish.) There’s also the strong possibility that the book will become about The Disease, and that the world of the novel will be constructed solely so that we can cry over people dying of AIDS, and we can rage against an uncaring society and a corrupt system and I don’t even care enough to finish the sentence that shit bores me so much. It turns out I didn’t have to worry; neither Hoolboom nor Coach House Books thought he was a social worker. Instead, they all seemed to think he was a writer who wanted to tell an interesting story in an interesting way with interesting characters. As it happens, they were right.

Hoolboom’s prose is casual and energetic, bordering on the Canadian Indie Style, but with enough discipline and control to avoid actually flying off into The Style. Though Auden seems to want to sublimate himself to Steve as the driving force of the story, it’s Auden’s strong, wonderfully developed personality that really shines through in sentences and paragraphs of The Steve Machine. I quite like this bit:

In my new dreams I savoured dinners with conversation so witty my guests ached with laughter, and all of them begged me to share their bed afterwards, startled by my perfect fashion sense and sexual athleticism. Shallow dreams, I knew, but sometimes even the unconscious gets tired of outputting Greek myths and new corporate logos. Meanwhile, in my waking hours, a small, angry man with a mouth in place of understanding hunted for blame. Like the hummingbird, he’d learned just one tune, and never tired of playing it. It was my fault. That’s what he let me know. Even if the day hadn’t started up yet, something somewhere was going wrong and I was to blame. When I spoke too frequently, this feeling would start creeping into conversation. Some were born with subliminal seduction, others with subliminal failure: it was a little trick some of us had learned to keep happiness from spoiling a view that had grown only too familiar.

There were two things I knew for sure when I tested positive. That I was going to die. And that I was going to hunt down the voice that was forever busy inventing new kinds of failure, and squeeze its little windpipe until it snapped between my fingers. I would not die guilty. I just didn’t have the time. (p. 98)

So much of The Steve Machine is about the roiling course of Auden’s attitudes and emotions as he becomes himself, the owner of his own true voice, in the face of his disease and blessing/curse of his relationship with Steve and the book they’re writing together. For every moment of despair there’s a moment of strength or apathy or affection. Interestingly, speaking of affection, I never really figured out if either Auden or Steve are gay; they clearly both like men, but there are passages that could indicate they might also like women. It just doesn’t seem crucial to the book or to their identities to pin a definite sexual identity on either of them. And that’s frankly refreshing. In literature, as in life, they are too many people whose sexuality eclipses all their other qualities to the point that it becomes the primary way you think of them as people (and don’t those people irritate you?), but there are just as many people for whom phrases like “I don’t like applying labels” actually means deep internal confusion, rather than the transcendence of labels that one imagines is the desired impression such phrases are intended give. Hoolboom ought to be commended for managing to create characters who actually achieve that transcendence.

Like Steve Reinke, Mike Hoolboom works primarily as a film and video artist. Though he’s written other books, The Steve Machine is his only novel to date. I do hope there will be others.”

Robson Reading Series: Mike Hoolboom (UBC Grad Gazette, Oct. 2, 2008)

The first novel by acclaimed filmmaker Mike Hoolboom, The Steve Machine, is an audaciously original story of the friendship of Auden, a lost and HIV-positive young man, and Steve Rienke, a video artist who can cure insomnia, lower back pain and the ability to fall in love. Together, the duo encounter much love, loss and laughter, as well as Yoko Ono, an orgy master, Leno and Letterman and the staff of Pizzabilities.

The Steve Machine by Mike Hoolboom by Drew Halfnight (Matrix Magazine Issue 82, Spring 2009)

The Steve Machine by Mike Hoolboom by Drew Halfnight (Matrix Magazine Issue 82, Spring 2009)

In The Steve Machine, the debut novel by Toronto video artist Mike Hoolboom, the reader encounters less a plot than a series of reckonings, less a novel than a video collage of memories, dreams and impressions.

After learning he is HIV-positive, Auden hauls anchor and moves to Toronto, an obscure purgatory of all-night doughnut cafes, hospital waiting rooms and featureless studio apartments. Once there he meets real-life video artist Steve Reinke, who helps him build a machine (read: write a book) that will record and process his new life with the virus.

An ethereal, fleeting presence, Reinke serves as Auden’s companion and alter ego. In meditations on Reinke’s videos and ideas, the aesthetic propositions underpinning The Steve Machine are given full play:

“Steve lived inside the books he encountered; he threw himself between the covers knowing that soon there would be no one left to read them. Oh sure, someone would always be able to pick up a book and go through the motions, twitching over miles of letters all lined up in a row like a firing squad. But to really read a book was to feel it as an echo of all the books written before it.”

And later:

“Personality was only an imperfect collection of memories, and now that art had set itself the task of leaving personality behind, we would pass in and out of one another like so many interchangeable parts. Like a machine.”

There is little action to speak of in The Steve Machine, but what does occur — an orgy, some office work, bouts of vomiting — unfolds like a most inconsequential dream. The real action is the steady circulation of pathogens in Auden’s blood…

At the end of the novel, Hoolboom permits a gust of humanity to blow through his hero’s otherwise cold, detached narration. In a night club, Auden gushes: “I looked down in horror to see that my foot was also keeping time with the beat while my pulse raced with an emotion that could only be named as joy. Ohmigod. I was enjoying this.”

After so much morbid exposition, the book’s sudden bright ending stings the eyes. Still, the effect is warming enough.

Amazon Review by Kevin Killian

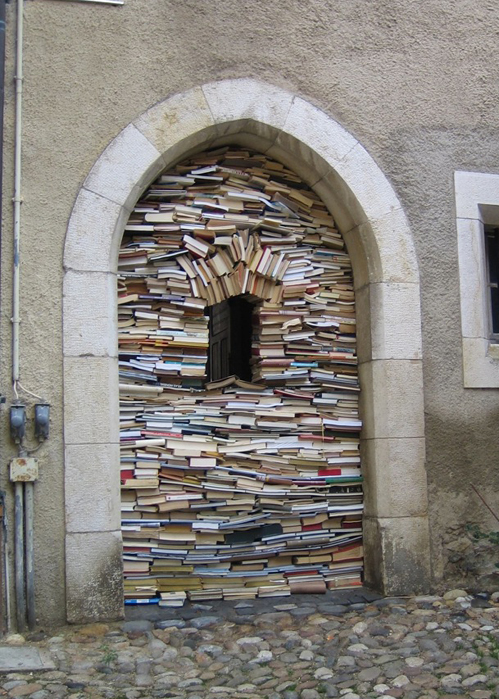

The Steve Machine is beautifully designed by Alana Wilcox and the cover photograph by Benny Nemerofsky-Ramsay is more evocative each time I look at it. It was Richard Canning who recommended this book to me, saying it was the best AIDS novel he’d read in years. And that is not a recommendation I take lightly, for Canning is the editor of Vital Signs, a recent anthology of fiction about AIDS that I consider one of the top books of recent times.

I had never heard of Mike Hoolboom, the writer, nor of the video artist Steve Reinke who Hoolboom has fictionalized into the hero of his modern morality fable. Now I feel I know them both well. I had the same reaction to this book as I had way back when, when I made my way through Tom Spanbauer’s novel The Man Who Fell in Love with the Moon – that characters one was in love with were populating entirely new fictional territory. And I resisted at first, for I don’t care much for “quirky” per se. Auden, a HIV-positive youth from the sticks, moves to Toronto and falls in with an arty crowd that has Steve Reinke at its center, and Steve begins healing him with the eponymous “Steve machine.” It sounded like a Louise Hay sort of cure for AIDS, based on a strenuous deconstruction of one’s personality and circadian rhythms. I kind of curdled inside, then recalled Canning’s thumbs up and decided to give it one more chance. Only a page or so later I realized that the concentrated whimsy and invention were working on me. I hate novels with charismatic heroes, from On the Road onwards, but for this book I make an exception. Steve’s aphorisms and theories are extraordinarily amusing and original, I learned to wait for each one the way her followers learned to wait for the next droplet of malice that fell from Dorothy Parker’s lips.

As the novel parallels the development of the so-called “AIDS cocktail,” it divides itself into two sections, despair and hope.

The only thing I didn’t like is that, perhaps in a bid to stay warmly humorous and voguishly ironic, Hoolboom doesn’t give us much of a love story. At least not in so many words. It wasn’t until the book was over that I realized just how much his two main guys felt for each other, and how they saved each other’s lives through the power of invention, of making up an alternate reality superior to the one science and the state had handed them. Bravo, Mr. Hoolboom. On every single page of your book there’s a mindblowing new idea; it’s a book that changes one’s consciousness.

The Steve Machine by Mike Hoolboom by The Pedgehog

Originally published in Smoke City Stories

www.smokecitystories.blogspot.ca, Friday, September 27, 2013

I was a bit wary of this book, because I am a somewhat boring person who is a big fan of linear narratives, and I tend to get overwhelmed by experimental fiction that wraps around itself. You know the kind of stuff I’m talking about. Anyway, I thought by the synopsis that The Steve Machine would be the kind of thing I didn’t like, the kind of novel you need a Masters in English Literature to begin to understand. But I was pleasantly surprised by how easy and compelling and even quite charming it was.

The story starts when Auden, our narrator, is diagnosed with HIV. He decides to pack up his life in Sudbury and move to Toronto, where he meets a few fairly strange people (as you do), including Steve. Steve is a video artist whose work is so innovative it teaches people things, like how to communicate with each other on a molecular level, and what’s going to happen a few minutes into the future. Steve has Auden write things down as part of “the machine”, which is the book. Yes, the book you’re reading. So it’s kind of trippy, but it is fun and weird and moving enough to be read on just one level, if that’s all you’re looking for.

After reading a few different books in which the AIDS epidemic among gay men featured prominently (most notably The Toronto You Are Leaving), it was fascinating to encounter this one which is set in the present day (ie the late 2000s) and still details a lot of the problems around stigma and prevention that were present when the virus first started to spread in the 1980s. The description of the clinic waiting room, the strange feelings, the mood whiplash, was extremely well done and terrifying. I liked the way the author dealt with Auden’s job and how he tiptoed around the diagnosis with his boss, and yet they were both comfortable with explicit sexual stories and Auden booking sex workers for him.

The extra complicating factor of this novel is that Steve Reinke is an actual, real person. The afterword addresses some of the lines between fiction and life, and it seems that Reinke was a pretty good sport about being used as a character in the book. It’s a funny thing to do, and I have to wonder what the author’s intent was – why not just create a fictional character? Anyway it didn’t make a lot of difference to my enjoyment of the novel but I’m sure if you know Steve this is something you want to check out.

Overall, I liked it. It was short and sweet, and definitely a quick read. There’s a lot to think about but it’s not too cerebral. One complaint: not enough Toronto. Otherwise, I would recommend it. Four CN Towers out of five.