Tom 53 minutes, video, 2002

This movie can be seen at: http://docalliancefilms.com/film/2137/?query=tom

This movie was re-edited in 2009, and shortened from its original length of 75 minutes to 53 minutes.

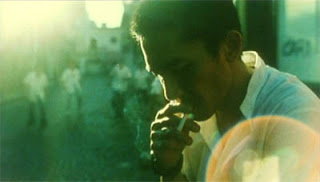

“A dazzling experimental documentary about notorious cineaste Tom Chomont. Tom narrates his recollections and transgressions against a dizzying array of found footage, video, super-8 and photographs. At moments, he appears in front of the camera, alternately flamboyant or fragile. His revelations cover a broad scope from sadomasochistic desire through existential vulnerability to an incestuous relationship. With this extraordinary portrait, Hoolboom creates a different kind of biography film, one that eschews traditional mimetic realism in order to depict the reminiscences of a fading life lived in the throes of image culture.” Diane Burgess, Vancouver Festival

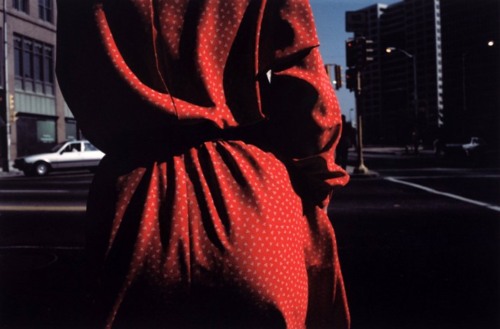

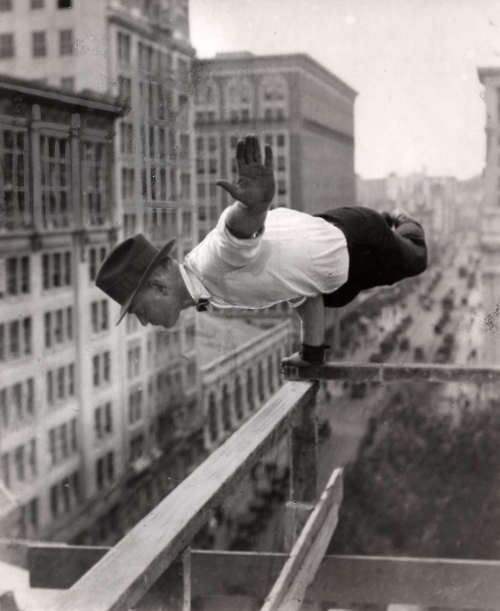

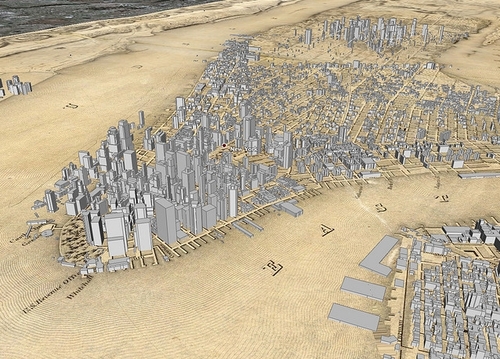

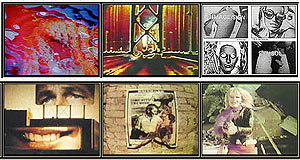

“Tom is a visually choreographed thought-scape, intermingling footage of Tom with found and archival footage ranging from the erecting of the Empire State building to Hollywood classics to much more abstract images, the film weaves Tom’s daily life and struggle with AIDS with distant memories and present fantasies.” Reeling Festival

“An uncommon biography of Tom Chomont-a key figure in New York fringe culture, a notorious video artist, ill with AIDS. The backdrop of the story: New York City… Hoolboom adopts an associative approach, taking dozens of film segments, from forgotten newsreels to the most well-known Hollywood moments-attempting through them to rebuild Chomont’s biography. The stories elucidate the fabric of the image and give them meaning: childhood memories, stories of incest, a mobster’s love or even the great white light that for Chomont symbolizes the beginning and end of life. The other star is New York City, images of which from various periods and from often incongruous angles play a part here. Utilizing all these visual elements, he constructs a new, fictitious biography that fills in the gaps left by memory and by those things located on the hidden side of the subconscious. The end result is a work with hypnotic effect-an uncommon experience.” Vivian Ostrovsky, Jerusalem Film Festival Catalogue

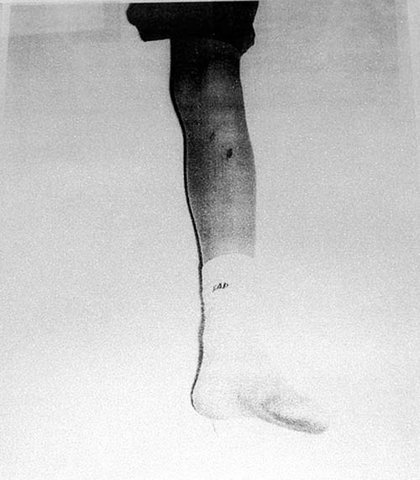

“Tom is a celebration of cinema and friendship—a dialogue between filmmakers. Hoolboom’s images mix and meld with those he has begged, borrowed and stolen. These are then punctuated with excerpts from many of Chomont’s own works, ranging from 1968’s Phases of the Moon to such 90s films as Sadistic Self Portrait and Head Shot. Attended by a sound design that is hauntingly beautiful, Tom is a deeply evocative portrait of a life lived through art—and an unforgettable testament to the friendship and respect these two men share.” Liz Czach, Toronto International Festival

“The maven of Toronto’s experimental film scene makes a sojourn to New York to pay tribute to a fellow artist: Tom Chomont, the maker of underground films such as Phases of the Moon and Sadistic Self-Portrait. In Tom , Hoolboom has created a typically idiosyncratic sort of biography, combining interview footage of Chomont (now suffering from AIDS and Parkinsons) with ‘found’ footage drawn largely from Hollywood and documentary sources, as well as Chomont’s movies. The subject’s personal history-an incredible story involving incest and New York’s gay fetish scene-is a powerful through-line for Hoolboom’s avalanche of gorgeous imagery.” Jason Anderson, Eye Magazine

“Prolific Canadian experimental filmmaker Mike Hoolboom pays tribute to a colleague in Tom… Mixing bits of stock footage and Hollywood images (along with clips from Chomont’s 30-plus years of filmmaking) in a rapid, allusive montage that follows the narration, the film creates a window on the possibilities of pure strangeness of one person’s life.” Liam Lacey, Globe and Mail

“A prismatic portrait of New York artist Tom Chomont, Mike Hoolboom’s latest is remarkable most for its approach. When one of Canada’s best filmmakers chooses to abandon shooting new footage in favour of found images it counts as a manifesto. Tom tells the story of Chomont’s life and work in glimpses using thousands of shards gathered mostly from other films. But unlike most remixes, Hoolboom does not attempt to collect the audience into a mnemonic whole, forcing us to recall the original source of the footage and comparing it to present use. Instead, he uses archive images the way authors use nouns.” Cameron Bailey, NOW

“…the screen is awash with images that provide an impressionistic corollary of the sensory equivalent of Chomont’s life. There’s a potent emotional power to Hoolboom’s technique, which subjects all the images it uses to the larger narrative of Chomont’s nakedly unrestrained testimony. The result turns the conventional wisdom of movies being larger than life on its head: Chomont’s real life looms much larger here than all these movie fragments added up.” Geoff Pevere, Toronto Star

“This fiction film is based on the life of filmmaker Tom Chomont (1942-2010), an emblematic figure of the New York underground. Its visual framework is derived from personal archives and filmed interviews, creating a veritable visual cyclone of Hollywood clips and films by Chomont (Phases of the Moon: The Parapsychology of Everyday Life (1968), Sadistic Self Portrait (1994), etc). Without falling into mimetic realism, the film concentrates on the reminiscences of a man nearing the end. Using New York as its backdrop, it portrays Chomont through his fantastic stories, illnesses (Parkinsons, AIDS), romantic relationships, and sexual practices (SM and fetishism), unveiling both his flamboyance and vulnerability.

An avant-garde filmmaker and photographer, Tom Chomont produced and directed over 40 films between 1962 and 1989. In 2010, filmmaker Jim Hubbard and director-restorer Ross Lipman (Senior Film Preservationist, UCLA Film and Television Archive) paid tribute to him at the Museum of Modern Art in New York with a screening of several of his works.” (Fringe Dreams by Karl-Gilbert Murray, Festival of Films on Art Catalogue)

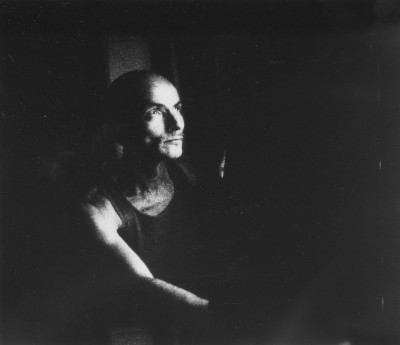

“The first shot in Mike Hoolboom’s film shows an arc lamp lighting up inside a film projector. This blinding light announces the symphony of images to follow. In the same way as a musician writes his score by playing with the expressive and emotional impact of each instrument, Hoolboom sketches the portrait of his friend, the artist Tom Chomont, by exploiting the special potential of each of the different image sources at his disposal. Black and white archives, contemporary images in video, super-8, photographs and excerpts from Hollywood films overlap, combine and are superimposed as Tom Chomont tells his story. A master of avant-garde cinema, he has directed homoerotic and autobiographical experimental films for more than thirty years. Suffering from AIDS and Parkinson’s he appears before the camera alternately flamboyant and fragile. In all sincerity, Tom’s voice-over retraces the important episodes of his life, composing a subjective autobiography marked by the image of his younger brother with whom he had an incestuous relationship. This new composition by Hoolboom looks death in the eye… Through the film’s powerful editing rich with references the story of this man, whose life was marked with the seal of transgression, is finally written into the official history of this period.” Yann-Olivier Wicht, Nyon

“I’ve seen that already!” How often one sits in the movie theater and wants to shout this out loud. In this case, however, you cannot blame it on the lack of ideas of the director/author, quite the contrary: The Canadian experimental filmmaker Mike Hoolboom has assembled his feature-length portrait of New York underground artist Tom Chomont mostly out of snippets from feature films and historical documentaries. This way he can illustrate Chomont’s stories-about his sexually uneducated mother, a child murderer, gay incest, AIDS death, all of this recalled in an almost “alien” fashion within an image flood from the twentieth century, where everything has been seen before.” Zitty

“The multiply awarded Canadian film artist Mike Hoolboom presents a fictive documentary. Tom is the film biography of a person that doesn’t exist and this person’s life in New York is traced, using already existing film scenes… Oddly funny, Tom has autobiographical notions and themes familiar from Hoolboom’s previous work.” Siegessäule

“Canadian avant-gardist Mike Hoolboom pays tribute to NYC artist Tom Chomont in Tom . Beautifully assembled effort is a dense collage of ‘found’ and appropriated materials aimed to capture essence of the suejct, rather than just the facts. Pic is of significant programming interest to cinematheques and experimental sidebars.” Dennis Harvey, Variety

“If, God forbid, P. Diddy ever made a movie about one of his heroes, the concept would probably sound a lot like Hoolboom’s Tom, a dazzling experimental picture that pays tribute to underground artist and filmmaker Tom Chomont. Like his Puffiness, Hoolboom doesn’t actually pick up his camera and shoot any new film-he instead appropriates chunks from Chomont’s extraordinarily large catalogue, and unlike Puffy, turns it into something new and exciting, and spellbinding. It’s the kind of film that grabs you, sucks you in, and practically hypnotizes you as your jaw gets closer and closer to your lap. I’m not sure what any of it is supposed to mean (especially the jarring finale that features famous Manhattan landmarks blowing up) but I don’t care.” City Newspaper, Rochester

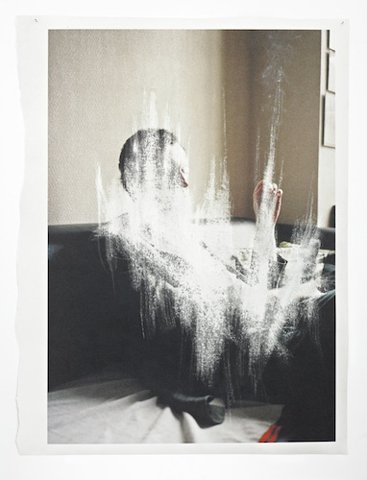

“I’ve always been fascinated by the work of Mike Hoolboom. From his cutting-edge Canadian satire Kanada to the less cryptic effort Frank’s Cock, Hoolboom the kind of movies that many Canadians are simply too afraid, or too unimaginative, to attempt. Untempted by mainstream fame or filthy lucre, Hoolboom makes films that challenge both the viewer and the medium itself. Here, he pulls off one of his most poetic feats ever as he chronicles (and that’s a term I use loosely) the life of Tom Chomont. Chomont is a bit of a legend below the radar. A man whose films have been the subject of a Museum of Modern Art retrospective and several academic essays, Chomont has been making movies for close to fourty years. He appears before Hoolboom’s camera as something of a spectral figure-gaunt, pale, trembling and suffering from AIDS. Hoolboom capitalizes on the ghostly image by superimposing images of Chomont over his own footage. The effect is stunning, as it shows us Chomont as something of a time traveller, moving through images of his own creation. Combined with stock archival footage, Hoolboom fashions a film that articulates the artist’s place in the world-without ever having to defend the creative position. It’s simply there, whether one chooses to embrace it or not. For those seeking the ultimate film-festival film, where experimentation takes precedence over formula, this is the one you won’t want to miss…A very soulful mediation on the life and work of filmmaker Tom Chomont. Director Hoolboom uses the medium to enhance his subject’s emotional reverie, resulting in a film that seems to spring into silver before the camera. A beautiful and emotionally taut homage, to both the man, and cinema.” Canadian Films Top Ten, Katherine Monk

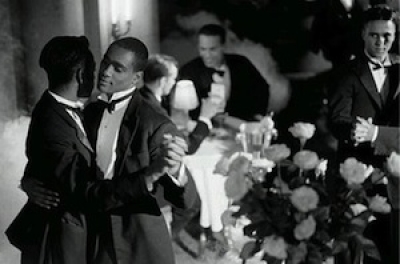

“A magical, hauntingly allusive collage, a celebration of a sexual and artistic outlaw, mixing found footage from across a century of American history. Home video, photographs, interviews, music and some of his own sexually explicit films build up an intimate portrait of Tom Chomont, photographer, filmmaker, leather fetishist and sado-masochist. Director Mike Hoolboom has fashioned a film which is hypnotically beautifully and offers a rare insight into Tom’s multi-faceted life, as he looks back on the joys and heartbreaks that include a gangster’s love, sex with his brother and a passion for art and experience.” London Lesbian and Gay Festival

“Tom is a look at the controversial New York based video artist Tom Chomont, but those wanting to get to know his art in an introductory way will need to get their primer elsewhere. The movie is much more about his life and the forces that have come to shape him than his art in particular, although his works are highlighted throughout the movie. Tom’s life has been damaged many times, first by his own isolated childhood and then by film, love, death, AIDS and even incest to make him the man he is today. And this is why Hoolboom can make Tom so much more than just another A&E biography-his subject has experienced the extremes of life as few have. Hoolboom has separated the film into two interweaving elements. The first is an eclectic mix of found and stolen footage and Tom’s own often shocking works. The second element is a look at Tom Chomont as he is today. With great style and verve he relates stories of infanticide, incest, S&M, fetishism and a rare white light which he imagines as both the beginning and end of all life. As these two elements come together, Tom takes on a magical almost eerily unnatural air-an air which is augmented by ambient trance music made deliciously visual.” Victoria Independent Film and Video Festival

‘One of the pleasures of the fetish scene is you don’t have to be beautiful to be a narcissist,’ says New York filmmaker Tom Chomont. ‘All of the ugly kids from high school can have their day in the spotlight.’ It’s hard to believe that Chomont was ever one of the ugly kids, but he certainly gets his day in the spotlight in this avant-garde documentary by Mike Hoolboom. In Tom, Chomont’s life unfurls in a style as unique as his own story. Found footage and archival film (including a fascinating survey of New York City over the years), home movies, photos and new video ‘stream past in a hypnotic rush’, says Hoolboom, ‘offering a subject whose skin is cinema, whose flesh and blood have been remade into the picture plane.’ Add in Chomont’s recollections of infanticide, sex with his own brother, S&M, fetishism, visions of a white light that illuminates both the beginning and end of life, and excerpts from some of his own films, and Tom evolves into a deeply emotional portrait of a lifelong outlaw now battling both HIV and Parkinson’ disease. This is a film that evokes as much as it depicts, and alludes as much as it describes. Hoolboom calls it ‘cinema as deja vu or deja voodoo’. We call it one of the most spellbinding and unforgettable films in this year’s festival.” San Francisco International Gay and Lesbian Festival

“This is almost a documentary of the New York artist Tom Chomont, looking at his life and work in the style of his films. It’s a surreal weaving of images and stories as Chomont occasionally talks about his childhood and how he lives with Parkinson’s Disease. The kaleidoscopic imagery is a mixture of original video, archival footage and clips stolen from mainstream films past and present. They’re edited together fluidly in often confusing combinations that are strangely beautiful and involving. It’s not terribly easy to watch, but it is absorbing, and the stories Chomont tells about his life are quite fascinating, even as he delivers them in a deadpan style accompanied by a collage of disconnected imagery. We also get a brief stroll through Chomont’s increasingly pornographic filmography-intriguingly arty museum pieces done in the same heavily edited and manipulated style. Over all, Hoolboom captures the man beautifully, although the film does leave major gaps in his life, bringing up questions that are never remotely addressed. But it doesn’t really matter, in the end this is a portrait not a documentary. And it’s rather lyrical and beautiful if you let it flow over you.” Rich Kline, UK

“Mike Hoolboom imaginatively edited together feature-film clips, industrial and educational films, found footage, home movies, old porn films, family photos and recently filmed video footage for this experimental cinematic portrait of underground filmmaker Tom Chomont. Through his subject, Hoolboom explores the limits of memory, the strength of family, the nature of sexual identity, and the power of the cinema-themes that Chomont addresses in his own films (Phases of the Moon, 1968; Re:incarnation 1973; Sadistic Self-Portrait, 1994; et al.) From Chomont’s childhood memories; his homoerotic relationship with his brother who recently succumbed to AIDS; and his entry into the sadomasochistic demimonde to his own confrontation with illness (Parkinson’s Disease) and his life in New York City, the film juxtaposes often jarring images to simulate the tricks that memory and thought can play… To document the first time Chomont saw his parents having sex, Hoolboom cleverly intercuts old blue movies with footage of elephants rampaging through the streets… Tom offers some startling and unconventional instances of montage.” MK, Baltimore Citypaper

“Tom is an affecting piece of cinema, an unconventional biography of New York underground filmmaker Tom Chomont. The film’s title is as short and simple as its subject’s life is thick with experience. Hoolboom splices together bits of found footage, split-second clips from Hollywood productions, pieces of Chomont’s own oeuvre of personal experimental film and footage Hoolboom himself took of Chomont. Though now ill with AIDS, Chomont is still sharp and ruminative as ever-his snapshot-like narratives of events in his life (from a brief, incestuous relationship with his brother to his own fetishes, hopes and dreams) overlay Hoolboom’s haunting images and sound design to create a multilevel depiction of a complicated emotional life lived past and present.” Erin Podolsky, Metro Times, Detroit

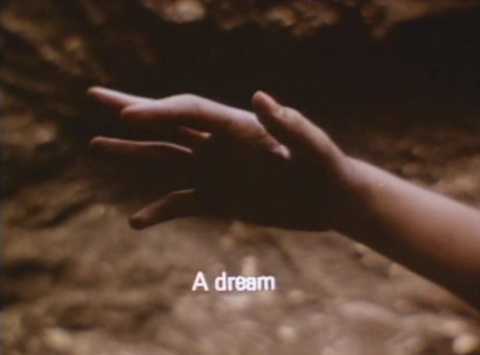

“This film leads us through an underworld of long forgotten images, of dreamlike moments that seem to become accessible only in a state of hypnosis; stored fragments of a youth and origin that we might be sharing with everyone else; a collective cinematographic memory of early years and imaginary landscapes of past futures. Tom is an ‘experimental’ documentary almost entirely made out of found footage, from unknown archival material to a famous Buster Keaton scene and from Hollywood to the work of Tom Chomont who is the subject of this movie. Chomont is a well known member of the New York underground scene, a filmmaker, a notorious video artist and narrator. In his film work Chomont tries to reconstruct moments of his past, to give them a shape that can be shown and shared. Chomont’s recountings are accompanied by a dazzling amount of pictures. This fragmented and unusual biographic construction expresses how liquid and layered a life story can be and how filled up our stories are with images that come from everywhere. Tom speaks about his youth, the relationship with his brother, of love, of his illness with AIDS and Parkinsons. He says that the pictures you make and fill rooms with (pictures of countries, animals, stars and neighbors) changes the image of your own face. Hoolboom shoots Chomont at home, among mutual friends and walking along the streets of the most photographed city of New York. Intimate moments alternate with archival images of streets filled with traffic and crowds in a city always under construction. It’s a movie about a beginning and a fading life, and about a fragile body weakened by illness. At the same time it is a liberating free fall in which air, height and water play an important role, next to numerous feature film fragments in which doors and windows are opened over and again leading to new rooms and discoveries. Hoolboom’s themes, such as cinema, history, memory, the body, (homo)sexuality and loss, come together in a dark and light, dense, fluent and tender portrait of a man, a time, a place and a state of existence.” Esma Moukhtar, Montevideo Catalogue

“Tom est quant à lui un documentaire expérimental. Avec ce film, le cinéaste et vidéaste Mike Hoolboom, nous livre l’une des œuvres les plus troublantes du cinéma canadien des dernières années. Tom raconte l’histoire de Tom Chomont, cinéaste expérimental, conteur, qui est atteint de la maladie de Parkinson et qui est maintenant affaibli par le SIDA. C’est face à ce destin tragique que le Torontois Mike Hoolboom a décidé de faire un film sur cet ami et collègue qui vit à New York. Ils discutent ensemble de censure, de sadomasochisme, de cinéma, de l’Amérique. Le recours sensible aux images empruntées, si caractéristique du style poétique de Hoolboom, est ici justifié par l’histoire de cet homme qui s’est toujours battu pour faire reconnaître autant son mode d’expression de la recherche artistique que son orientation sexuelle aux accents de scandale. En dehors des images reçues du cinéma commercial, et en dehors des images d’archives de la ville de New York, c’est à une histoire secrète et intime à laquelle nous sommes conviés, à travers un voyage visuel et sonore assez fabuleux. Tom vient d’être élu l’un des dix meilleurs films canadiens de l’année par un jury de vingt critiques.” QuebecPlus

“He was astonished at the course that life could take, at the way things that had seemed once to concern him so much—indeed to revolve around him—could turn out to have nothing to do with him at all.” Michael Chabon

“…the function of the film is clear: it completes life, it fills the holes in life. It allowed the narrators to see-it allows them today to recount events which they did not personally encounter, fragments of History which are not part of their own history.” Marie-Claude Taranger

Tom is an “experimental” feature-length documentary made almost entirely of found footage. This is cinema as deja vu, or deja voodoo, many moments will feel all too familiar, though they’ve been projected now onto the surface of a life to make up this most unusual of biographies. The history of a city, New York City, the most photographed city in the world, operates as a backdrop for the life of Tom Chomont, a key member of the New York underground, a notorious video artist, AIDS sufferer, raconteur. His fantastical stories punctuate the weave of pictures, and a rare white light which he imagines as both the beginning and end of all life. As the decades roll past, excerpts from hundreds of films, some archival documents, some well known Hollywood moments, stream past in a hypnotic rush offering a subject whose skin is cinema, whose flesh and blood has been re-made into the picture plane. A biography about biographies, made possible, inevitable even, by the society of the spectacle.

New Queer Cinema and Experimental Video by Julianne Pidduck

Barbara Hammer insists, polemically, that ‘radical content deserves radical form.’1 This statement marks a longstanding association between feminist and lesbian and gay filmmakers and the avant-garde. Some ten or fifteen years into the ‘New Queer Cinema,’ the word ‘radical’ is provocative. What is ‘radical’ about new queer form and content? Can we concur with B. Ruby Rich when in 2000 she proclaims New Queer Cinema’s ‘short sweet climb from radical impulse to niche market?’2 Such a narrative afford concise periodisation, where this cycle emerges in the 1980s through AIDS and queer activism and the independent festival circuit, and dies a tragic death with Boys Don’t Cry (Kimberly Pierce) and Happy Together (Wong Kar-Wai) in 1999. However, rather than relinquish the ‘radical impulse’ to the niche market, I’d like to argue, somewhat polemically, for the continuing relevance of formal experimentation as an irritant and a source of renewal for New Queer Cinema.

As a point of departure, it is worth returning to Rich’s initial characterization of the movement: Call if ‘Homo Pomo:’ there are traces in all of (these films) of appropriation and pastiche, irony, as well as a reworking of history with social constructionism very much in mind. Definitively breaking with older humanist approaches and the films and tapes that accompanied identity politics, these works are irreverent, energetic, alternately minimalist and excessive. Above all, they’re full of pleasure.3

In this chapter, I use Rich’s suggestive passage to consider several ‘experimental’ videos by Mike Hoolboom, Richard Fung, Sadie Benning and Cathy Sisler. Apart from Benning who is American, the other three makers work in a Canadian context, and all four have screened their works in queer milieu while receiving acclaim in fine arts circles. These videos are not selected as ‘representative’ of the diverse field of queer art video, although I point to some common elements. Indeed, I would suggest that queer art video is characterized by a singularity of form and content that unravels pat discourses of identity, politics and relationality. In this chapter, I use the singularity of each project to interrogate the terms ‘new,’ ‘queer,’ ‘cinema.’

‘New’: Mike Hoolboom’s Tom

‘Newness’ is part of the mythology of this cycle. Drawing from the momentum of American independent cinema, the first wave of New Queer Cinema boldly appropriated elements from existing traditions: excessive surrealist imagery from Kenneth Anger and the American underground (Poison , Todd Haynes, 1991); the European avant-garde (the works of Ulrike Ottinger and Rosa Von Praunheim); a flamboyant performativity and excessive costuming reminiscent of Warhol and Jack Smith’s 1963 Flaming Creatures (Paris is Burning (Jennie Livingstone, 1990), Velvet Goldmine (Todd Haynes, 1998); the erotic rewriting of genres such as the road moie from Jack Kerouac to My Own Private Idaho (Gus Van Sant, 1991), The Living End (Gregg Araki, 1992) and Isaac Julien’s video installation The Long Road to Mazatlan (1999); an amoral ‘criminal’ expression of desire that may be traced back to Genet, Pasolini, Rimbaud (Swoon (tom Kalin, 1991), Edward II (Derek Jarman, 1991), Les Nuits Fauves (Cyril Collard, 1992), Head On (Ana Kokkinos, 1998); the queer legacy of the Harlem Renaissance and American ‘race’ movies of the 1930s and 1940s evoked in Looking for Langston (Isaac Julien, 1989) and The Watermelon Women (Cheryl Dunye, 1996) respectively. Such extensive borrowing underscores how New Queer Cinema is rooted in earlier aesthetic traditions, notably an auteurist legacy that is almost exclusively male.

Mike Hoolboom’s 75-minute video Tom (2002) makes explicit this legacy in a homage to New York filmmaker Tom Chomont. Richard Dyer situates Chomont within a 1970s avant-garde aftermath to the gay American underground, noting that his films Oblivion (1969), Love Objects (1971), Minor Revisions (1979) and Razor Head (1984) accentuate the intimate qualities to be found in the works of jack Smith or Gregory Markopolous; however, the personal qualities of Chomont’s films are offset by a certain ‘strangeness in the filmmaking, much use of negative reversal, superimposition or remarkable set-ups.’4 Hoolboom’s Tom takes up some of these strategies to create a vivid and densely intertextual portrait that incorporates historical documentary, fictional and surrealist film footage, home movies, and recent digital video footage of the aging filmmaker. A rapidly morphing image track is often treated through negative reversal, colour treatment, repetition and speed variation. Meanwhile, an equally complex soundtrack layers extensive interviews with Chomont, industrial noise, and sudden bursts of music: a sultry jazz saxophone line, sampled single notes and arpeggios on the piano.

An established and prolific Canadian ‘fringe’ filmmaker and writer, Hoolboom’s sexuality is often almost incidental to his work (as with Chomont’s films). In keeping with a queer preference for oblique accounts of subjectivity, Tom‘s palimpsest imagery and breadth of cultural reference serves to disassemble rather than reify ‘identity.’ Geoff Pevere observes that Hoolboom’s ‘primary aesthetic is the exposure of the limits of discourse… how narrative film practice represents the systematic elimination of… (the photographic image’s) infinite, unknowable, ambiguity.’5 Hoolboom situates his own ‘fringe film’ practice within a tradition where ‘from (the cinema’s) very inception, a scatter of artists have trained their sights to other ends-sometimes as provocation, or political exposition or material demonstration.’6 Tracing a continuity from the auteurist (gay) underground to Hoolboom’s own practice, clips from Chomont’s films are cut into the video as are images of Hoolboom filming, or simply observing just off-frame.7 A recurring sequence of Chomont editing 16mm film stock on a table on a New York sidewalk insists on filmmaking as an artisinal and creative industrial practice.

Hoolboom’s work shares New Queer Cinema’s strategies of pastiche and the social constructionist reworking of history. Tom presents a mediation on the intersection of history, (cinematic) representation and the ephemeral qualities of human memory and corporeality. Hoolboom creates a sound-image canvas, a ‘portrait’ that does not follow a standard biographical trajectory, but is rather anchored in Chomont’s face, voice and fragmented recollections. After a brief opening sequence in Chomont’s apartment, the film cuts to a wide-angle shot close in on his bald, elfin face with the Manhattan skyline in the background. In voice-over, Chomont declares: ‘My name is Tom and this is my city.’ Cut to an aerial shot, soaring over the Statue of Liberty towards Manhattan. This shot introduces a structuring analogy between the human body and the modern city-not just any city, but New York in 2001. Hoolboom comments:

“Manhattan is a small island which changes constantly in its quest for the new… it rips down buildings and makes new ones. The destruction of New York has been imagined many times, not only in cinema, and the September 11 attacks are (a particularly horrible) part of this continuum… The body of Tom is framed by images of New York’s destruction… And in this image of a city constantly refigured lies a metaphor for personality itself, as we see Tom incarnated as a drag queen, as S/M top, S/M bottom, as brother and son, as film then video maker, always changing appearances, interests, sexual predilections.8

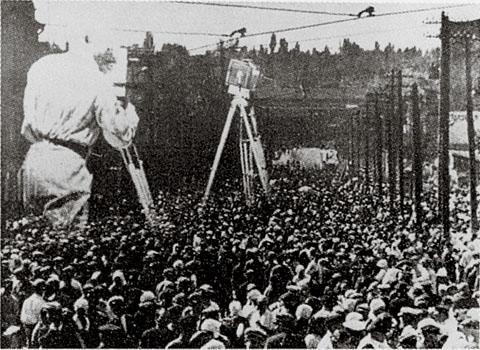

The dialectic between destruction and renewal is integral to Tom, which incorporates clips from disaster movies, documentary footage of skyscraper construction and building demolition, and early twentieth-century Lower East Side street scenes. The resulting visceral but abstract portrait of the city is a time-travelling version of the great modernist ‘city symphony’ films Man with a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, 1929) and Berlin, Symphony of a City (Walter Ruttmann, 1927). Juxtaposed with Chomont’s voice-over childhood recollections and sampled industrial sounds, the soundscape and narration are non-synchronous with the image track. Parallels between memory and experience and the city are at once broadly historical and oddly intimate.

Something strange happens to time in Hoolboom’s films. The linear logic of event-as-sequence-conventional history, narrative, biography-dissolves her. New Queer Cinema’s claim to the ‘new,’ at least if read through the logic of just-in-time production and niche marketing, is incommensurable with Tom‘s rich temporality. Gilles Deleuze claims that narrative cinema (what he calls the ‘movement-image’) unfolds in a perpetual present governed by a vision of human intentionality and agency. Within this system, ‘aberrant movements’ (cinematic aspects that exceed or digress from causal sequence) are suppressed to preserve the hegemony of ‘normal movement.’ The dominant form of the ‘action-image’ centers the human body in the frame as transformative agent within a determined milieu. Aberrant movement stands for the transformative capacity of time as both before and after the perpetual present of the movement-image: ‘There is no present which is not haunted by a past and a future, but a past which is not reducible to a former present, by a future which does not consist of a present to come.’9 For Deleuze, the ‘time-image’ describes a different cinematic trajectory, where the spatial ordering of narrative time gives way to ‘pure optical and sound situations’ where ‘time is no longer the measure of movement but movement is the perspective of time.’10

Hoolboom’s work deploys several aspects of the time-image.11 ‘False continuities’ of surrealist editing abound, where the splicing together of incommensurable fragments creates unexpected articulations of memory, causality and meaning. Juxtaposed with Chomont’s narration, the ‘city symphony’ dialectic of disintegration and frantic rebuilding personalizes the cinematic residue of historical social space and long-dead citizens, while depersonalizing and extending the peculiarities of individual recollection. Most germane to new queer cinema, Tom jumbles what might loosely be called ‘the history of sexuality.’ For instance, the frequent use of surrealist ‘dream-images’ (dissolves, superimpositions, deframings, special effects) transfigures objective perception into a subjective modality. In Tom , the reconfiguration of saturated symbolism and banal popular culture creates a disturbing and unexpected account of mortality, generation, and (queer) corporeality. The dissolution of cinematic ‘sense’ through a barrage of the time-image’s ‘pure sound and optical situations’ corresponds to a disintegration of corporeal and biographical boundaries.

Pale, wizened, balding and suffering from Parkinson’s disease and HIV/AIDS, Chomont’s hands and body are unsteady and his quavering voice often is overcome with emotion. Hoolboom intercuts his alternately gnome-like and childlike subject with fetuses, Martians, microscopic organisms and children. The co-presence of Tom’s childhood, young adulthood and present parallels the restless city sequences, where different decades collide without respect for generic convention or temporal sequence. For instance, in voice-over Chomont links his homosexuality with an intense relationship with his brother who was his main companion in an itinerant childhood. The boys were lovers briefly as teenagers, and Chomont’s account of this relationship coincides with a montage of historical footage of boys playing in the street and exploring an empty farmhouse. This imagery is made strange through compulsive repetition and speed variation, overwriting found historical footage with same-sex desire and the taint of incest. In a cumulative editing strategy, Tom incorporates many shots of children and adults entering and leaving rooms, opening and closing doors and windows-a simple scenario suggesting exploration, transgression, voyeurism, or more broadly the life cycle as a series of thresholds and passages.

Chomont describes how his brother explored S/M and fetish sexuality before him, and recounts the scene of his brother’s death form AIDS, a scene that foreshadows his own imminent death. In Tom, the rapidly morphing, fragile subject evokes most of all the unsteady passage of time-the haunting duration of the recollection-image, the fragile corporeal temporality of illness and everyday experience. For Deleuze, cinematic forms are equated with ‘images of thought,’ and Hoolboom’s reassembled moving image form generates fresh ways of conceiving illness, corporeality, desire and history.

Old Tom, New Tom by Dirk de Bruyn (July 2005)

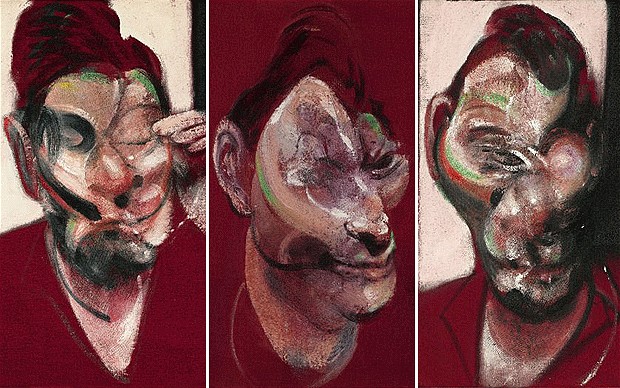

“When one looks at something, one’s not only looking at it directly, but one’s also looking at it through the assault that has already been made on one by photography and film .” Francis Bacon

Though still a relatively recent activity, working with the moving image in the digital age has a history. This record resides in an evolving cultural process of looking that Bacon identifies above. It can also be referenced back to that non-narrative tradition of the moving image that runs through experimental film and video production. Although that is a practice that has become problematic in Australian conditions, an experimental / “avant-garde” tradition of film and video art continues internationally to offer critical ways of articulating the human condition, especially at those margins at which such an oppositional practice itself tends to be situated. Canada, a place with which Australia shares many parallels, offers a continuing, lively tradition in this area. Mike Hoolboom’s Tom (2002 75 minutes, Video) is presented here as exemplar evidence of such a continuing spirit. Tom , created using digital technologies, can be considered in terms of both old and new media. It is a work that has been historically informed by the work of a previous generation, like the work of film artists Al Razutis and Jack Chambers. This is a connection that will be examined further to underline the regenerative resilience of Canadian moving image art. What this ongoing tradition offers a contemporary digital practice is a fully formed mastery over technique and an articulate, mature language that speaks directly to the viewer.

Tom is Mike Hoolboom’s biography of filmmaker Tom Chomont and his City, New York and includes excerpts of his films including Phases of the Moon (1968) and Sadistic Self Portrait (1994). Tom tells of his struggle with HIV and Parkinson’s disease and disarmingly recounts confronting memories of infanticide, incest, fetishism and death. These revelations are then processed through an array of technique, pulled out of Hoolboom’s lifelong immersion in fringe film , bringing to bear layered photos, home movies, video, appropriated archival and found footage and images directly out of the video rental store, to supply a cathartic visual processing machine. Arthur Kroker’s ideas about panic bodies and excremental culture permeate both the structure and content of this video. It is in part an examination of the erasure and loss of 80’s experimental film while at the same time re-inventing it as a resilient form of moviemaking for the digital age; A “Vital Sign” that there is a creative tradition of moving image art worth persevering with and re-connecting to .

The Old and the New

Experimental Film and video continues to flourish outside Australia in North America and Europe. It evolves and continues to be distributed through such organizations as, for example the Lux in London , Sixpackfilm in Vienna , Light Cone in Paris , Video Data Bank in Chicago and CFMDC in Toronto . Such work remains part of a line of alternative cinematic investigation, sitting outside the mainstream, and often critiquing and analysing that commercial centre. Hoolboom, as a long-term card carrying participant in this project, offers a sophisticated, confronting and historically aware renewal of that Canadian specific “cinema we need” .

Lev Manovich creatively appropriates frames from Dziga Vertov’s Man With a Movie Camera (16mm 1929 Russia) as foundation topography for the prologue to his seminal 2001 text: The Language of New Media and further recycles these images as Interface, to signpost different sections of the text in that book. Manovich’s branding of Man With a Movie Camera as meta-film is welcome and telling and he states that: Vertov is able to achieve something that new media artists still have to learn- how to merge database and narrative into a new form . But there is a New Media myopia at work here, because a well documented international history of moving image work emerged after and “out of” Vertov. This is an apparently invisible history even to Manovich and certainly here in Australia. Hoolboom offers the latest incarnation of this “invisible cinema”.

We will further examine how Hoolboom’s Tom offers a contemporary merging of Vertov’s database and content and outline how this is a method and form already reworked by generations of experimental or personal film artists like Al Razutis and Jack Chambers in Canada and informed, in Canada by theorists such as George Grant, Harold Innis and Arthur Kroker to give this work a particular technological spin. I would suggest that in such a constellation a history for new media art is there for the taking.

Why zoom in on Canada when there are so many global possibilities? It is more than the fact that Hoolboom is Canadian and Tom is a Canadian film. It is more that a focus on Canada underlines to an Australian audience that such a practice can arise from a familiar place, a place with which we share a number of commonalities including our parallel, colonial histories. Canada offers the possibility of a dispersion of our short-sightedness.

Within the new world of such ex-colonies as Canada and Australia there is often a myopic understanding of our own history. The idea of Terra Nullus itself sets up a tradition of denial and erasure. There was plenty here before the first fleet arrived. There is a formula here that continues to be repeated. The new tends to replace the settled, the old with an associated forgetting. Such a dysfunctional tradition silently permeates all aspects of our culture, including creative and technological production. In Australia the emergence of the digital saw a concurrent collapse of critical, financial and exhibition support of experimental film, with a resulting decline in production.

This Vital Signs Conference itself is evidence that the new cycle of production that replaced it, which has been complicit in the forgetting of the experimental, now faces threats to its own funding and identity. It could be argued that such moves on digital production are strengthened because of New Media’s lack of connection to its own roots in experimental or avant-garde moving image production.

In Canada, as elsewhere, the historical connection has been maintained. Earlier on Canadian artist Jack Chambers, for example, saw personal film as an area of creative production where a colonial denial could be addressed. The problem for new world art, wrote Jack Chambers in 1969 is that it “runs the risk of an impoverished materialism through omitting the historical dimension.” But “Where North American artists do embody an historic dimension is in the medium of personal filmmaking. They form a major part of film’s “roots” and are making enormous advances in the organic-mind growth of this art.”

Kroker’s observation that the Canadian discourse on technology “is situated between the future of the New World and the past of European culture” further credentials Canada as a colonial site for examining a New/Old Media interface or amalgam. This is a status Australia shares without the lucidity and spine of Canada’s integrated fringe filmmaking activity, exemplified in Hoolboom’s work, which here as already stated has fallen by the wayside, has dis-connected in the scramble in and out of the new. An impetus to re-focus and re-claim this tradition for an enriched Australian creative practice of the moving image is overdue.

The Direct

Tom offers a timely and critical renewal and development on from previous experimental work in its ability to communicate directly to its audience through its visual imagery. This idea of “the direct” is perceived as critical to a definition of experimental film and video by Small. Small’s Direct Theory contends that experimental film as a genre does its theorising intrinsically and directly through its methods of assembly, through the making of the work itself.

Small develops a checklist to help define the genre of experimental film and video: a-collaborative construction, economic independence, brevity, non-narrative structures, technical innovation, avoidance of verbal language, mental imagery and reflexivity. These characteristics make a compelling road-map for digital construction as well and Small’s characteristics of mental imagery and reflexivity are especially relevant to an understanding of Tom.

Though alien and irrelevant to popular cinema what Small brings to the surface as unique to experimental cinema is often part of the accepted wisdom of art in other media. The tactic of “the direct” is also effectively employed by painter Francis Bacon and also in the work of Jack Chambers (as will be discussed later). Bacon’s work offers evidence of this strategy in painting, photography and the space between a series of images. His paintings, are a unique and personal vision of “the body in ruins” which straddle the figurative and the abstract, and are framed by his interest in photography and cinema. Bacon’s strategies echo the way that Tom impacts immediately and viscerally through its image flow to its audience. We will examine Bacon’s ideas further before we return to the Canadian connection and its project with technique.

Van Alphen outlines how Bacon’s work, often described as reflecting the disturbed pain of the artist, also settles and imbues a sense of personal loss on the viewer. Through distortion and ambivalent representations the artist disorients the senses of the viewer and communicates directly at a bodily level to his audience.

Sylvester’s incisive interviews with Bacon relay this process in the artist’s own words. It becomes clear, for example, that Bacon has an obsession with the open mouth in his work and this is a moment appropriated from cinema. This fixation is grounded in the frozen silent shock of the nanny scream from Eisenstein’s groundbreaking Odessa Steps montage sequence in Battleship Potemkin (Russia B & W Silent 66 minutes 1925) . Within Bacon’s practice there is also a persistent returning to Muybridge’s pre-cinema serial recordings of figures in movement. This is the same immersion that occurs in Tom . There is the same historic referencing of cinema and pre-cinema in the mass of re-contextualized found footage from which Tom is constructed.

Bacon works through the photograph and memory rather than through sittings with his subjects. “ I find it less inhibiting to work from them through memory and their photographs than actually having them seated there before me .” It is a relationship that reminds one of Mike Hoolboom’s relationship to Tom Chomont. Tom’s revelations are often routed through other imagery and other representational forms before they arrive at the viewer. This imagery is often needed to absorb and process the impact of Chomont’s revelations about his life and his family.

Bacon repeatedly worked with images in series, using the triptych to create relationships: I see every image all the time in a shifting way and almost in shifting sequences. In the series one picture reflects on the other continuously and sometimes they are better in series than they are separately because, unfortunately, I’ve never yet been able to make the one image that sums up all the others. So one image against the other seems to be able to say the thing more.

The Holy Grail of the singular image is not at issue for Hoolboom as Small also indicates. Bacon is after a further distillation. Hoolboom’s focus is the moving image itself and includes its reflexive examination. His is a documentation and articulation of these changing relationships. The play of shifting sequences of imagery and subtle flow is the body of his work. He presents a string of mental imagery, externalised thought, that resonates with Bacon’s reflexive thinking about his own work. Hoolboom unfolds in the moving image that body in ruins that Bacon fixes in his painting. For both artists, the effect on the body of the audience is targeted along this shared trajectory.

Bacon regards breaking through media determined habits about the way we take in information as critical to his art: We nearly always live through screens- a screened existence. And I sometimes think, when people say my work looks violent, that perhaps I have from time to time been able to clear away one or two of the veils or screens . To achieve a direct impact on his audience Bacon’s method connects back to Russian Formalist strategies like de-familiarisation and baring the device articulated by Shlovsky. What I want to do is to distort the thing far beyond the appearance, but in the distortion to bring it back to a recording of the appearance . Small also identifies these as critical operations for experimental cinema (reflexivity and technical innovation). At its best Tom also breaks, disconnects from its screened existence.

For Bacon communicating directly to the body requires a denial of storytelling (perceived as an intellectual activity). It’s a very very close and difficult thing to know why some paint comes across directly onto the nervous system and other paint tells you the story in a long diatribe through the brain . The moment the story begins to be elaborated the boredom sets in; the story talks louder than the paint.

This tension between storytelling and some visual visceral impact also exists in Tom, where Tom Chomont’s voice intermittently breaks through the image flow to relate some event from his life, usually confrontational and/or catastrophic, offering an element of story that the imagery feeds off and takes up. The story is not being elaborated by this image flow but seem to take us to a place where the images impact directly onto the nervous system to help our bodies work through Tom Chomont’s enunciated “home truths”.

The Virtuosity of Technique

For Hoolboom this direct use of imagery arises out of his role in the project of Canadian personal filmmaking and Canadian intellectual thought. A discussion of two Canadian feature length films: Jack Chamber’s Hart of London and Al Razutis’s Amerika can help to underline a connection between the direct and technique . They too arise out of and help define a Canadian fringe filmmaking practice that is organised, technologically articulate and self aware with a critical political dimension that addresses issues of image and database re-appropriation, non-narrative structure and abstraction. It is interesting that three films also critically and self-reflexively re-deploy historical material as content.

Al Razutis’s Amerika (1972-1983 152 minutes single or 56 minutes triple-screen 16mm) is a ” feature-length experimental film which was created one reel at a time to function as a mosaic that expresses the various sensations, myths, landscapes of the industrialized Western culture (1960’s -1980’s) through the eyes of media-anarchism and avant-garde techniques .” To investigate various forms of filmic representation and their underlying ideologies Razutis uses an array of time-lapse, optical printing, video and audio synthesis techniques to interrogate the mainstream and continually re-contextualize the film’s own construction. The serial construction and the out-there confronting meshing of technique with political concerns has been taken up by Hoolboom in his work. With Tom he brings this tension clearly back into the personal.

Quite apart from the argument of its invisibility, of it having been erased, there is also an argument that the avant- garde or experimental has been neutered within new media production. What has been this repressed other to mainstream cinema; the experimental, the avant-garde, the underground, fringe cinema, graphic film and video art, Wollen’s counter-cinema, no-budget and personal filmmaking makes its prodigal return to the centre of New Media production. But the avant-garde no longer spits in the face of institutional art. The avant-garde has become materialised in the computer manifesting McLuhan’s “ all centre without margins ”. The avant-garde returns emptied of its political edge and rhetorical grounding.

Such an homogenisation can be further outlined by focusing in on a specific technique or technical strategy. Single frame time-lapse, a strategy often utilised within experimental production with an interval-o-meter attached to the movie camera, becomes a redundant coupling in the digital domain. With real time recording now seamlessly malleable, its duration shrunk and stretched at will in postproduction, time-lapse has not so much disappeared as a trick or special effect but re-emerged embedded within the form of the technology itself.

The enabling of collage through cut and paste commands, the convergence of graphics, titles, text, sound and a host of animation strategies with image manipulation and tweaking, sound and live action into computer based editing packages like Macromedia Director, Adobe After Effects and Final Cut Pro digitises the Experimental film-maker’s strategic toolbox and promises to turbo-charge her tradition. Yet it seems the prodigal returns neutered, in zombie-like fields of homogenised clones.

Having begun his project pre-digital Al Razutis’s trajectory mirrors these changes and inconsistencies. Razutis’s career long take on technology is now accessed at any computer keyboard. His drive and commitment appear to dissipate in the endless expansive fields of information overflow that can define the web.

His spraying of “The avant-garde spits in the face of institutional art” on the brand new screen at the Vancouver Cinematheque, “ruining” it forever, has long been part of avant-garde folklore. His retrospective at the Osnabruck European Media Arts Festival of old and new work in 2002 hands him contemporary kudos and relevance. Collage remains king inside the computer. Re-located online as Visual Alchemist/Activist Razutis’s project with technique continues. Yet his larger than life invocations are harder to hear, less distinct amongst the mushrooming cacophony of numerous online voices and multiple technical games.

Such a softening, diffusion or demobilization of the avant-garde’s critical edge is addressed and reclaimed in the hyper- layering, editing and collection strategies employed by Hoolboom in Tom .

Jack Chambers’painting, his writing and film work further illuminate the connection between technique and the “direct” strategies employed by Bacon. Hart of London (1968-70 80 minutes, 16mm) by Jack Chambers is a lyrical mixture of archival and newsreel footage of London, Ontario mingled with images shot by Chambers himself. The film introduces a deer that is stalked and killed in downtown London, setting up a struggle between civilization and nature that permeates the film, through its life and death cycles and the everyday images of life in London. It is through the visionary collage of this material, its superimpositions and pace that the film attains its cumulative impact and reputation: The four films of Jack Chambers have changed the whole history of film, despite their neglect, in a way that isn’t even possible within the field of painting.

Chamber’s move from his realist painting to film was realized through his silver paintings. They were concerned with transforming space to time. As the viewer moved the image fluctuated between a negative and positive image. These “instant movies” were Chamber’s response to the new demands that photography had placed on representational painting and moved him though an aesthetic history of cinema to its current technical state, which merges image and sound.

There are traces of Bacon’s “direct” cosmology in Chamber’s thinking. Chambers underlines the critical role of history when he posits that ‘Technology is a historic process that learns from itself and perpetuates what it learns by a tradition, thereby passing on the accomplishments of its own history.” Such an integrative process passes technique through Chambers and Razutis to Hoolboom, for example, and this is Manovich’s evolving database (here already in play before the emergence of the digital). Technique is viscerally integrated into the body. It is a conditioning that evolves over time to the manipulative practice, to the adaptation of results to the nervous system ” Meaning is communicated directly to the body and then, for Chambers, like Bacon, the boredom does not set in.

For Canadian philosopher George Grant this can be a difficult and critical process, especially in the colonies. The tension at play concerns the margins resisting the centre. “ We can hold in our minds the enormous benefits of technological society, but we cannot so easily hold the ways it may have deprived us, because technique is ourselves ” . For Grant the modern self is being colonised from within, perhaps mapped as Foucault’s technologised self and McLuhan’s body extensions and connects with Van Alphen’s reading of Bacon as loss of self. Loss becomes difficult to express within such technical topographies, though Parker Tyler has observed that “ The void itself is a ground .” It is at such blind spots that Bacon or Chambers can inject their vision directly into the nervous system and Bacon can elicit the “exhilarating despair” of the repressed “other” coming into view.

Grant implores “only in listening for the intimations of deprival can we live critically in that dynamo. We need to articulate a world of “dead identities, dead vision, and an overwhelming sense of inner dread and anxiety”. Artists whose inner life is infected by displacement and rage (Razutis), leukaemia (Chambers) and HIV (Hoolboom) are well placed to use their colonised bodies (their Panic Bodies) as database to directly articulate such depravity. When the site of such activity takes place within a colony that itself acts as a victim , artists need to develop a layered vision to articulate and transgress that implosive situation.

Chamber’s articulation of his creative practice as Perceptual Realism seems to parallel Kroker’s reading of another Canadian thinker, Harold Innis’s work as Technological Realism. Innis “sought to preserve some critical space in Canadian discourse for the recovery of an authentic sense of time” Innis argues that to foster a stable western culture like Canada, the countervailing centrifugal and centripetal forces of time/duration and space/territory need to be in balance. The migration of technique from the United States, as advanced technological society, to Canada (as advanced dependent state) is evidence of the triumph of the colonising monopolies of space: the global electronic media that is seen to be in need of tempering by a cultural impulse to recover time, to remember.

Now at the post-modern (articulated by Kroker with his compacted swaggering prose, akin to Hoolboom’s gung-ho layered pastiche of image and technique) the fault lines between time and space have heated and morphed the hype into hyper: hyper-drive, hyper-real, hyper-space, hyper-aesthetic. This is the triumph of technique as the post-modern (Razutis’s legacy): the current container of Capitalism’s “progress”.

Within Innis’s cultural script the personal cinema of Chambers and Hoolboom especially can be read as a bulwark, enabling authentic civil discourse, a cultural remembering within Canada by re-ordering the debris of commercial media activity. Unfortunately for Razutis his displacement to Canada as “asylum seeker” from California retraces the trajectory of technique itself and thus performs a double whammy on his enraged body. There is a trace of Hoolboom’s relationship to Razutis in the subject of Tom; New York experimental filmmaker Tom Chomont, which allows for a revitalisation of Razutis politically charged project.

Summation

And so we arrive again at Hoolboom who, like Razutis, also had his stint in Terminal City. His “Three Decades of Rage” acts as witness advocate and fan to Razutis’s rant and his affiliation to the Escarpment School in Ontario accesses the pedigree of Chamber’s leukaemia terminated project. His layered database consists of the history of Canadian reflexive thought, a life lived in North American avant-garde film, his own activism within its making and the daily reminder of his own HIV colonised body. This database is directly incorporated into the body of his work, re-constituted in the biography about biography that is Tom.

Tom salvages the media detritus that we all consume in our daily lives and transforms it into the matter of some externalised mental bustle that is personal and unique. It is not garbage in, garbage out after all. The neutering of the avant-garde at the moment it is enabled within the computer does have a twist, it does not have to be “terminal”. Hoolboom has figured out how to turn his scavenged shit into gold and meet Grant’s challenge in a post-modern context by listening to his body.

It seems as if the surface of cinema itself is the body that is being marked and reconstituted and “the personal” forever challenged and changed by the infection of this material into the psyche. As observers there is a directness about this infection that makes it our infection, bubbling away in our heads, eyes, heart and so on. We can walk away from the cinema and our screens with that self belief back in our bodies; that the tools, the strategies, the technique can be found to re-invent our selves out of the “new chaos” that Kroker maps out: “unlike billboards in the age of pavement, these advertisements are injected directly into the veins of the post-flesh body like bar codes burned into flesh ” There is value in history after all. This is what Tom gives to me.

It can happen here. It has happened before.

Dirk de Bruyn

July 2005

Notes

Sylvester, David. Interviews with Francis Bacon Thames and Hudson London 1975: p 30

There are a number of terms that are used interchangeably: fringe film, personal film, experimental film and video, film and video art. This reflects a kind of homelessness for this area of art production that now seems to be also reflected in what is now happening with terms like new media, digital media, multimedia, interactive art and so on.

See Kroker, A., M. Kroker, and D. Cook, Panic Encyclopedia: the definitive guide to the Postmodern Scene. CultureTexts, Macmillan Basingstoke 1989

Kroker, A. and M. Kroker, Body Invaders: Sexuality and the Postmodern Condition . Macmillan Education Basingstoke 1988

Kroker, A. and D. Cook, The Postmodern Scene: Excremental Culture and Hyper-aesthetics . 2nd ed. St. Martin’s Press. New York 1988It is understood that a number of readers may not have had access to a screening of Tom, especially Australian readers. For those there are descriptive elements in this text that leave a trace of the work. Yet even this video’s absence from view creates its own mischievous impact on discussions about erasure, denial and forgetting. I think the primary task is to make the argument for re-connection can be effectively enough understood without a viewing of Tom.

see http://www.lux.org.uk/ > viewed 8 November 2005.

http://www.sixpackfilm.com/?lang=en&p=info > viewed 8 November 2005

http://fmp.lightcone.org:8000/lightcone/us/acc-us.html > viewed 8 November 2005

http://www.vdb.org/default.html > viewed 8 November 2005

Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre Website: < http://www.cfmdc.org/ > viewed 8 November 2005

See Elder, Bruce. The Cinema We Need

in Canadian Forum Vol LXIV No. 746 (February 1985) pp 227-243. this article that was critical to a discussion around “the cinema we have” and “the cinema we need” that occurred in Canada in the 80’s

Manovich, Lev The Language of New Media Cambridge, Mass. ; London: MIT Press, 2001: p 243

see: Grant, G., Technology and Empire : Perspectives on North America . House of Anansi. Toronto. 1969

See: Innis, H.A., The Bias of Communication . University of Toronto Press. Toronto 1952

Innis, H.A. and M.Q. Innis, Empire and Communications. University of Toronto Press. Toronto 1972

Arthur Kroker’s own (Kroker, Arthur Technology and the Canadian Mind Innis/McLuhan/Grant New World Perspectives Montreal 1984) is a good overview of this tradition and indicates how these thinkers are connected to each other. In fact Kroker’s relationship and building on the thinkers he investigates compliments Hoolboom’s (and others such as Phil Hoffman and Barbara Sternberg) relationship to Al Razutis, Jack Chambers, Rick Hancox,

Joyce Weiland, Michael Snow and others.

Chambers. Jack in Elder, Kathryn (ed) The Films of Jack Chambers . Cinematheque, Ontario 2002: 35

Ibid: 43

Kroker, Arthur Technology and the Canadian Mind Innis/McLuhan/Grant New World Perspectives Montreal 1984: p 7

Small, Edward Direct Theory: Experimental Film as Major Genre Carbondale : Southern Illinois University Press, 1994

Ibid.

Van Alphen, Ernst . Francis Bacon and the Loss of Self Reaktion Books London 1992

Sylvester, David. Interviews with Francis Bacon Thames and Hudson London 1975

Sylvester, David. Interviews with Francis Bacon : p 40

Ibid: 21

Ibid: 22

Ibid: 82

see Shlovsky, Victor. Art as Technique in The Critical Tradition. Ed., David H. Richter, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989

Ibid: 40

Ibid: 18

Ibid: 22

see Al Razutis Website: http://www.holonet.khm.de/Visual_Alchemy/film_cat.html#amerika viewed 9 November 2005

Manovich, Lev The Language of New Media : p 307 -to paraphrase Manovich’s: In short, the avant-garde became materialised in a computer.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media:The Extensions of Man. McGraw-Hill Toronto 1964, p 2

Brakhage, Stan in Elder, Kathryn (ed) The Films of Jack Chambers. Cinematheque, Ontario 2002: 45

Chambers, Jack in Elder, Kathryn (ed) The Films of Jack Chambers. Cinematheque, Ontario 2002: 47.

Ibid: 13

Ibid: 35

Ibid: 35

Grant George Technology and Empire : p 137

Quoted by Kardish, Larry in Elder, Kathryn (ed) The Films of Jack Chambers . Cinematheque, Ontario 2002: p 186

Sylvester, David. Interviews with Francis Bacon Thames and Hudson London 1975: p 83

Grant George Technology and Empire : p 142

Kroker, Arthur. Technology and the Canadian Mind : p 22

Margaret Atwood makes this argument in Survival : A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature House of Anansi Toronto 1972

Kroker, Arthur. Technology and the Canadian Mind : p 124

A partly endearing moniker for Vancouver.

Hoolboom, Mike. Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada . Gutter Press Toronto 1997: pp 56-73

Kroker, Arthur and Weinstein , Michael A. Data Trash: The Theory of the Virtual New World Perspectives, Montreal 1994: p 109

Old Traces on a New Body by Dirk DeBruyn

Elements of New Media moving-image work can be traced back into the body of experimental film. This is a trace that has been erased under Australian conditions. It is argued that such an overwriting is a ‘traditional’ cultural response also evident in a marking of the migrant as ‘New Australian.’ Such blindness can be contrasted to the situation in Canada. There a tradition of reflexive dialogue between technology and identity has been maintained in the move from the old to the new. As a representative text, Canadian Mike Hoolboom’s personal digital-video work Tom (2002) effectively migrates old experimental filmmaking techniques into the digital ‘new.’

Tom is hard to categorize. A hybrid video, benefiting from the convergence in digital media, it can be read as an experimental documentary, a fiction, biography, autobiography, an animation, a historical document, or all of the above. It documents the private and public life of New York film and video artist Tom Chomont’s struggle with HIV and Parkinson’s disease as he recounts memories of infanticide, incest, fetishism and death. The video also excerpts Chomont’s short films including Phases of the Moon (1968) and Sadistic Self Portrait (1994). This is at time a confronting work, not specifically because of the HIV backdrop to this story but because of the taboo subjects of infanticide and incest recounted in the video. Assembled from scavenged footage and diaristic imagery, this material has been reprocessed and layered through an array of digital effects.

This digital work has been influenced by a long line of North American avant-garde practice that includes painter and filmmaker Jack Chambers and also enunciates ideas outlined by Brazilian media theorist Vilem Flusser about migration. Hoolboom’s work can be framed historically through Canadian theorists on technology such as George Grant and Harold Innis and also Arthur Kroker’s more contemporary panic theorizing. The resultant structures can be read as the architecture of a phenomenologically remembered history of the body and cinema.

The New as Eraser

It is asserted that there is a connection between new digital media and the old analogue ‘materialist’ media of experimental film. Small’s ‘direct theory’ indicates that the experimental has had a history of dealing with its images conceptually.1 Malcolm Le Grice, structuralist filmmaker, founding member of the 1960s London Filmmaker’s Co-op states in Experimental Film in the Digital Age that ‘The tradition of experimental film and video has already provided the basis for exploring these concerns (of non-linearity) not as a response to the new technology but as a consequence of artistic reflection on the human condition.’2

Locally, there has been a vigorous ‘tradition’ of experimental film emanating out of Melbourne, facilitated by Cantrill’s Filmnotes since the early 1970s, independent screenings and more organized activity through the Melbourne Super 8 Group (early 1980s), Fringe Network and MIMA (Modern Image Maker’s Association). With the increase of digital production in the 1990s, MIMA (now a national organization) changed its name to Experimenta, embracing New Media more emphatically, and moved away from analogue moving-image work. Cantrill’s Filmnotes, an independent font of experimental documentation and rhetoric, also ceased publishing after more than twenty years of activity. As a participant and a witness to such shifts, I would suggest that this ‘shift’ went beyond a change of emphasis and that, in fact, such analogue activity ceased to be addressed within and profiled by cultural institutions. Such work at best ‘returned’ to an underground subsistence often in what has become known as ‘micro’ or ‘boutique’ cinema environments. With film artists Marcus Bergner and film critic Vikki Riley, this writer was involved in one such ‘response’ at the Café Bohemio in Fitzroy in the mid 1990s.

So, the suggestion being made is that the connection between analogue and digital non-linear moving-image production and public profile was experienced as ‘lost’ under local Melbourne conditions. Canadian experimental filmmaker Mike Hoolboom’s Tom is presented here to suggest that such an outcome was not ‘inevitable.’ This shift has played out differently in other localities. Tom signposts a historical line of practice that survived and migrated successfully into digital production in a manner not evident in Australia or Melbourne particularly.

Again, speaking from personal observation, when this writer’s creative practice migrated from such old technologies of 16-millimetre and Super 8 film production to the new, in some virtual way my parents’ initial migration to Australia from the Netherlands in the late 1950s was being re-enacted. Migrating to New Media was like being asked to become a ‘New Australian’ again. ‘New Australian’ was both a populist and official term in Australia in the 1960s used to identify and make ‘welcome’ the migrants in their ‘adopted’ country. Those who wore this term were implored to forget their old idea of who they were, their history. It is all about the future, leave the past behind by coming ‘here.’

For the migrant, whether geographic or technological, there are resistances to such ideas. It is a double message. To be embraced as a ‘New Australian’ had a pejorative edge, as an empty officially sanctioned term or identity that placed those so named on an outside masquerading as inside. Becoming a (New) Australian assumed and expected an erasure of your past. In a way you were being reused, recycled, but seen to be of limited value in this new equation. Vilem Flusser may say that such a migrant experience now captures a general impact of technology.3 We are all overtly mobile as migrants, nomads, stateless, or in at least two states at once.

Ironically, there is a tradition of the way the new displaces the old that can be read into such discounting, marginalization of erasure and this sense can be applied to ‘New Media’ in Australia. This is a tradition of erasure and denial founded on that moment when a British Flag was posted to maker the arrival of the First Fleet on Australian soil coupled with the implication ‘there is nothing here.’ My parents were initiated into this mindset as ‘New Australians,’ and I was reconstituted into a New Media maker where the past had no perceived or recognized currency. In this way the gesture of ‘there is nothing here’ repeats itself through ideas of national identity, its institutions and its cultural activity. Terra nullius is itself a tradition. We place new things on the table and pretend it’s a clean slate. Yet we have a history that needs to be identified. Australians have ‘form.’

Canada

In such a locality capable of sabotaging its own sense of ‘place,’ there is a potential for some self-aware reflexive New Media work to address the situation. Tom is presented as such a work. It is no accident that these strategies arise out of another ‘settler colony’: Canada. There too a colonial mind-set, Margaret Atwood contends, has led to a victim mentality. ‘Let us suppose, for the sake of argument, that Canada as a whole is a victim, or an “oppressed minority” or “exploited”… Let us suppose in short that Canada is a colony.’4 Add to this Kroker’s observation that the Canadian discourse ‘is situated between the failure of the New World and the past of European culture’5 and we can identify further commonalities.

The problem for new-world art, wrote Canadian experimental filmmaker and painter Jack Chambers in 1969, is that it ‘runs the risk of an impoverished materialism through omitting the historical dimension.’6 But ‘Where North American artists do embody an historical dimension is in the medium of personal filmmaking. They form a major part of film’s “roots” and are making enormous advances in the organic-mind growth of this art.’7 It is within such an orientation that a historical connection has been maintained in Canada. It is a connection to which Hoolboom is responsive. It is a maintained critical tradition that further exemplifies Chamber’s assertion that ‘Technology is a historic process that learns from itself and perpetuates what it learns by a tradition, thereby passing on the accomplishments of its own history.’8 Through the critical thinking of Canadian theorists like George Grant, Harold Innis and Arthur Kroker it is argued that this ‘historical’ method enables the margins to resist the centre.

For Grant a resistant historic attitude to technology was required to preserve a civil society’s ‘common good.’ Grant argued that ‘We can hold in our minds the enormous benefits of technological society, but we cannot so easily hold the ways it may have deprived us, because technology is ourselves.’9 Already, the framing of colonization not only between nations but also as residing within the individual is evident here. Grant’s observation that in this situation ‘only in listening for the intimations of deprival can we live critically in that dynamo’10 offers a fault line out of this predicament taken up in Kroker’s postmodern theorizing about New Media and Hoolboom’s synchronous moving-image work. Kroker’s need to articulate a world of ‘dead identities, dead vision, and an overwhelming sense of inner dread and anxiety’11 was utilized in his postmodern theorizing about trash culture12 and panic bodiesl.13

According to Kroker, Innis ‘sought to preserve some critical space in Canadian discourse for the recovery of an authentic sense of time.’14 Innis argues that to foster a stable Western culture like Canada, the countervailing centrifugal and centripetal forces of time-duration and space-territory needs to be in balance.15 The migration of technique from the United States, as advanced technological society, to Canada (as advanced dependent state) is evidenced in the triumph of the colonizing monopolies of space (that is, the global electronic media). As if reworking Grant’s criticism into dynamic form, Innis argues the need for a cultural impulse to recover time, to remember. In this constructed cultural script the personal cinema of Hoolboom (and Chambers) can be read as enabling authentic civil discourse, enabling a cultural remembering within Canada. Both artists achieved this by critically reordering the debris of commercial media activity.

Tom

The painter Francis Bacon observed that ‘When one looks at something, one’s not only looking at it directly, but one’s also looking at it through the assault that has already been made on one by photography and film.’16 Having contextualized Tom within Canadian media criticism I now wish to frame Hoolboom’s work within this kind of looking, one that suggests a visceral awareness of its own historicity.

The ability to construct a complex visual narrative from disparate visual material is a developed skill that is the product of that evolving dialogue with technique that the artist journeys through, to get on top of their chosen art form. Often quite apart from the content of the work, the painter or the sculptor develops an intimate relationship with the materials used. This involves the development of an array of cluster of techniques that, Chambers has already argued in the case of film, can be transferred as a developing knowledge, a process between artists over time. Hoolboom’s video arrives on screen after a number of generational cycles of such processing of technique.

There is a mixture of the collector, the database, the gleaned and the personal present in Hoolboom’s video, as is a narrative of catastrophe and decay, brought home through a methodology of collage and metaphor. It registers on Chomont’s HIV-riddled body and on the real and imagined streets of New York.

This database includes black-and-white and colour shots gleaned from industrial films, educational documentaries and Hollywood blockbusters, often thematically arranged in sequences of doors, water, New York, construction and so on; sped up, slowed down and frozen; time-lapse and pixilated films; double and triple exposures; cinema verité video footage, personal and found photographs; animated artifacts; excerpts from Chomont’s own films; hand-processed, abstract, personal and so on. Such a list articulates parallel orchestrations of both technique and content. This is the promenade of ‘technical images’ that Flusser identified: ‘The universe of technical images, as it is about to establish itself around us, poses itself as the plenitude of our times, in which all actions and passions turn in eternal repetition.

Anecdotally and conversationally driven by Tom Chomont’s recounting in voice-over or directly to the camera is the remembering of often difficult, significant events of his life. Such ‘revelations’ are then interspersed by long setions with music and sound design, with no verbal (oral) storytelling. Yet these images address and continue this oral flow.