Copyright and biography: an interview about Tom by Joan Sandberg (June 2002)

Mike: When I was six years old my father told me how I was going to die. He said that in the moment before death the whole of my life would flash before my eyes, and is it just because I’m a filmmaker that I can’t help thinking of this as a film, a film we spend our whole lives trying to make, that we are making even as we sit together in the theater.

When it came time to make this movie about my friend Tom things weren’t going well. He’s had Parkinsons for years, a disease which causes him to alternate between shaking uncontrollably and paralysis, and as a result he lost his job, without savings, and then, in a careless late night moment, he became HIV positive. I went down to see him and we took a walk, slow walk around Elizabeth Street and stopped not long after on a bench a few blocks away. Something about the light on his face, the feeling this afternoon would never come again, urged me to take a picture. But when I saw the photo later, it didn’t look like Tom at all. What I was seeing was the emulsion maker, the lab chemistry, the glass grinders who made the lens. This small person in front of me couldn’t be Tom, not my Tom, the magnificent talker and fearless sexual adventurer. I realized then that I would never see him for the first time. That a history of pictures lay between us, so I began making an inventory of these pictures, and the result is what you see.

Joan: This isn’t a typical biography.

Mike: Most bio-pics feature testimonials from famous friends, exclamations of talent and importance, reminiscences, moments from the memory highlight reel. But what if you wanted to make a movie about someone’s unconscious? Asking wouldn’t get you closer. And as Mike Cartmell pointed out to me, recurrent themes in an artist’s work, the use of landscape or water, for instance, or sexual transgression, is not particularly a sign of the unconscious, which is more likely to erupt in a moment never repeated, the hapax legomena of a life. I wondered if it would be possible to construct a biography using pictures of places the subject had never visited, conversations never spoken, people never seen. And found, at last, inevitably, that no, it wasn’t quite possible. At least not for me. But there is a great deal in Tom which pursued this line, for better or worse, and sometimes to my surprise Tom would confirm yes, this really happened, like the scene where the two kids see their parents having sex. It seemed the further away from Tom I got, the closer I became. And of course this movie, like any other, was about a training of attention, your antennae goes up for all things Tom, and you begin to attract certain experiences, people, events, and all this makes its way into the film.

Joan: How did you the two of you meet?

Mike: I met Tom in the winter of 1981 in New York City, the only place I’d ever visited that seemed like home the instant I arrived. Stepping off the bus I fell into a concrete embrace and it’s been heaven ever since. That night I trooped off to watch a show of Tom’s small, beautiful diary films in a theater devoted to these exotic delicacies. Afterward, bursting with enthusiasm and Budweiser, we clambered up to his apartment and talked all night, and as the words flowed I noticed the room filling with light. There, in the wee hours of the morning, Tom’s postage stamp of a kitchen began to bloom, but I put it down to the Budweiser at the time. Besides, I’m Canadian. Repression and politeness are my credo. So just because this fantastical white light was spilling all over the floors was no reason to ask, I was a guest after all. In the years since, this luminous visitation has proved a reliable companion to our speaking, and I was astonished to learn, only recently, that everyone Tom spoke with didn’t experience it in just the same way. In a letter to me he described it to me like this:

“I’m less in touch with it at present, but I remember that in connection with the light I had that near-death experience, you know, the one of going into the light and presences being there on the way. All sound and light were there, fragments of voices and sounds and people were present, and if I let go and passed into it, the light and sound would gather into a single note like a heavenly choir. I felt some apprehension because entering fully into it seemed like dying or leaving the world forever. Then just at the last concern for someone I knew pulled me back and I wondered if it was possible to go into the light and still be in the world. It began like a dim star in the very center of the darkness. I had seen it many times while meditating. Sometimes it was blue or red or outlined by halos of changing colours. Sometimes it took forms which I came to feel were projections of my mind. It seemed like the sounds and voices created there were the result of the mind’s attachment to worldly things. This primal light and sound was the place my personality drew from to create experience.”

I remember coming home one Sunday morning and finding an empty ladder which my father had been using to trim the neighbor’s overhanging trees. There was a pair of sheers on the driveway and a trail of blood leading into the house. He was on my bed, unconscious, and the ambulance came and took him away. He revived after a few days and told me that he had seen a blinding white light, and that he had risen from the bed and walked into it, feeling an almost unbearable happiness. He was on the threshold, about to enter fully into it, when a hand tapped him on the shoulder. It was an angel (my father was raised Christian) who told him, ‘I’m sorry, it’s not your time yet. You have to go back.’ Deeply wounded, he looked back to the bed where he lay unconscious and headed back into his body. After three days in a coma, he woke up, and fully recovered.

The white light he experienced is not uncommon, scores of similar accounts have been issued by those close to death, and this light is the one conjured by Tom in our meetings. During a mescaline flashback, Tom returned to the moment of his birth, leaving the womb in a blaze of white light which slowly devolved to become the material world: mother, table, doctor, breast. Similarly, at the end of his days, he expects the world will dissolve once more back into a white light containing all light, sound and experience. This feeling of eternity which he conjures is a rare gift.

Joan: There’s a lot of found footage in the film. Why is that?

Mike: Copyright is an assertion of capitalist identity, I own equals I am. This is my car, my house, my life. What this flagrant copyright violation allows is a questioning of basic identity tenets. Where does one person stop and another begin? What does it mean to make a biography, the most personal form of filmmaking, while using footage which is entirely alien to the subject? I think the found footage functions in at least two ways. Firstly, it explodes the contours of the subject, he is no longer contained or containable, no longer bound to a particular set of experiences, with a determined history, and the inevitable judgments that history demands. It questions where the limit of one person is, most clearly felt in disease transmission perhaps, where a single moment, intimate and intense, the moment of orgasm, can implant the HIV illness, and live on in the infected person until their death. We are all of us affecting each other in small and large ways, and to suggest some of these echoes and reflections, and insist that they too are part of ‘the subject,’ of Tom, the found footage was used.

There were also practical considerations. Some mornings Tom couldn’t get out of bed, or walk across the street. While not aiming to downplay the role of illness in his life, neither did I want to reduce him to his afflictions. He is, we all are, so much more that. The found footage was a way of introducing the feeling of being with Tom, the places his conversation moves him towards, the magic of him.

Joan: Caspar Stracke is credited as a ‘ghost co-pilot.’ What was his role in the making of Tom?

Mike: The film began as a collaboration with Caspar Stracke, a German fringe media artist living in New York. He was so luminous, so funny and smart, that I just wanted to hang out with him, and making a film together seemed a good way to do that. This was exactly half right and half wrong. It turned out our working methods were entirely contrary. I have a mania for scripts and planning, while Caspar creates on the fly. He is also an accomplished AVID editor, so is able to discover things on machines which I don’t even know how to power up. I arrive at the edit room with stacks of paper and notes and exact instructions on how to proceed. He arrives with an open mind and an agile wrist. After a year of this, we stopped talking entirely, it was terrible, and then made up, we’re good friends now, but for a while there…

For all his free-flowing, rhizomatic brilliance, Caspar is still German, and you know the Germans, they have rules. The first rule was: no talking. He said you Canadians love to talk, talk, talk in your films, the head title is hardly finished when the talking begins. So for a year we worked on the film and there was no dialogue, no voice-over, nothing. There were certain colours which had to be avoided because, in his opinion, they ‘belonged’ to other makers. Ditto with formal strategies. He had a genius for creating loops which I adored but he would quickly wipe them off the edit machine claiming they were too Martin Arnold-ish. When we split up, I slipped a number of these back into the project. I wasn’t concerned about copying anyone, this film was a critique of all ideas that attached themselves to originality, subjectivity, genius, singularity, and if Tom was going to be ‘contaminated’ or occupied by foreign material, then so was I.

Caspar was also responsible for the tone of the soundtrack. For years I’d been hooked on vaguely romantic kitsch, but Caspar introduced me to a brave new world of laptop composers, glitch electronica, dark isolationists et al. Now I can listen to ventilator hums and be perfectly satisfied. He opened my ears, and that was a great gift.

Joan: Tom sounds very emotional when he speaks about his life.

Mike: I spent one magical afternoon with Tom on Elizabeth Street, in Larry Gottheim’s apartment, found through a friend’s friend, which turned out to be in the same block as Tom. I asked him some perfunctory questions about family and friends but mostly I sat back and bathed in this intense white light, and watched in astonishment as his recountings were accompanied by an uncanny change in his face. This was not recollection, but a reliving of events, he wasn’t describing his mother for instance, he was his mother. He cried often that afternoon, as the pain of his family’s death, his father and brother, were borne again, as if for the first time. His speaking that afternoon was used in snippets throughout the movie.

Joan: There is a great emphasis on Tom’s relationship with his brother.

Mike: Yes, somehow they were doppelgangers, best friends, and as Tom describes in the film, even lovers for a brief time. He moved in with his brother after coming back from Europe (where he had an experience of the complete break-down of language, traveling broke through many countries with a lover who didn’t speak English. When they arrived in Berlin, they both found they could hear other people’s thoughts.). He found his brother immersed in a sadomasochistic practice which involved ritual shaving, and he was put off, alienated. But when his brother died, Tom put on leathers of his own and began frequenting the clubs his brother went to, making scenes with some of his brother’s once lovers, and finally committing himself fully to s/m, first as a top, then as his movements became more erratic because of Parkinsons, as a bottom. His sexuality is at least in part a grieving for his lost brother, a way to remember him again.

Joan: There is a section in Tom which shows excerpts from his films and videos. Could you comment on his work?

Mike: Tom had made just under fifty movies since 1961. In the 1980s he switched to video which he’s still making, there must be at least thirty by now. Most are short, diary-like portraits, formally concerned, with rapid cutting (especially the films) which bring together small moments in a series of theme and variations. Oblivion for instance, describes the visit of a young man to his apartment, rituals of looking and undressing, and the cold winter after. It is a very intense, sublime erotic. Much of the film, like much of his work, has black and white high contrast film underlying colour reversal, which floods light into the picture, causing bodies to glow, faces to shine from within. This simulates the white light I mentioned earlier, and especially amongst his intimates, which remain the primary subject of his films, he is quick to show their bodies pulsing with light. He describes his own practice as a kind of nostalgia, a way to hold onto moments long gone. But in their shuddering, circular montage, they don’t feel at all sentimental. Excerpts from Tom’s work appears in its own section, named and played in chronological order, but they also appear scattered throughout the work, used as ‘found footage,’ in the same way as a Hollywood thriller, a newsreel, or my own films.

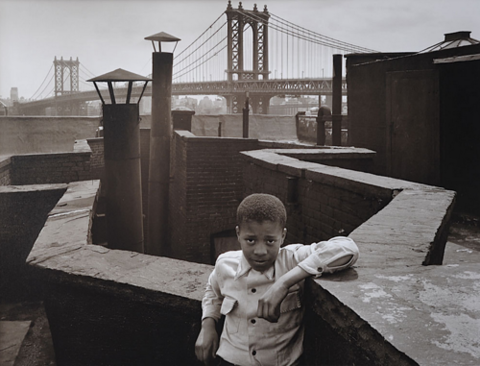

Joan: Tom shows many images of New York City.

Mike: The movie is framed by images of New York’s destruction, the first time by water, and then by fire. Manhattan is an island, so any ‘development,’ its rush to embrace the new, is accompanied by the destruction of what’s already there. The methodical destruction of Manhattan has been on the city’s drafting boards for the past couple of centuries. And of course there are numerous examples from the movies as well. I took this changing skyline as a metaphor for Tom’s incarnations. He has gone through such radical shifts in his life, and appears in the film as long hair hippie and bald man shaving, s/m top and bottom, drag queen and leather man.

Apart from being a biography, Tom is also a city film, in the tradition of the old city symphonies. New York shares with other large centers a certain narcissism, never mind its port status, it remains fascinated with itself. This fascination takes many forms, and contributes to the fact that it remains the most photographed city in the world. There is hardly a fire hydrant, apartment block or restaurant that does not appear in a movie somewhere. Moments from its motion picture history, whether in feature films, newsreels, documentaries, and personal essays, make their way into Tom.