House of Pain 50 minutes, 16 mm, 1995-8

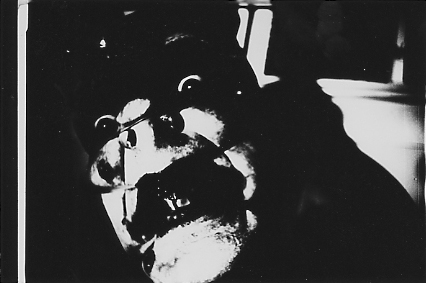

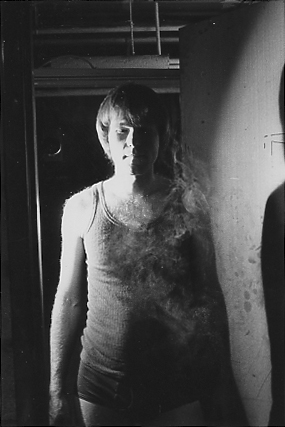

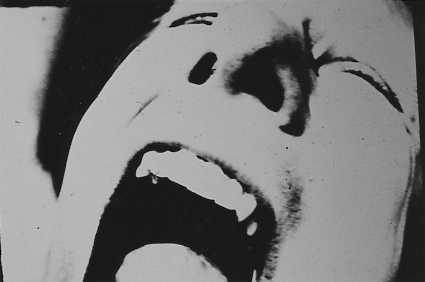

A hybrid of DeSade and Dali, House of Pain is a nightmare that takes place between sleep and death where the performers appear as mute hallucinations. House of Pain features a hallucinogenic blend of the domestic and perverse. Hoolboom’s unerring cinematography fascinates and fetishizes, never straying far from the surface of his subjects, converting them into dark objects of magic and transformation. They are also profound testaments of the body at its limits, filled with a harrowing dream vision whose fantastical vantages lend the body a rare grace.

“The Canadian avant-garde has found its Salo, and its name is House of Pain. Prolific, hugely talented Toronto/Vancouver/Toronto experimental filmmaker Mike Hoolboom’s new feature must be the most transgressive Canadian film ever made. Shot in black-and-white and printed in colour to achieve its luscious sepia-like tones, House of Pain‘s four parts simultaneously seems to celebrate and be revolted by that House of Pain in which we all reside: the body. Hypnotic, hallucinatory, entirely wordless, and completely beyond the pale… the film reads like a nightmarish, nocturnal-emission compendium of avant-garde, cinema-of-shock history.” Jim Sinclair, Pacific Cinematheque

“The prolific experimental filmmaker Mike Hoolboom’s new work is in fact a collection of four short pieces thematically and stylistically related. Described by the director as a “psycho-horror in four parts,’ there is indeed plenty in House of Pain to shock, alienate, confront and revolt its audience. At the same time, there is also a pervading passion and tenderness that suffuses the piece, most evident in the beauty of its cinematography. Hoolboom’s recent filmic concerns seems to be dealing with the very elemental nature of life, with corporeal existence at its most basic yet most profound. The body is represented as having an existence independent of consciousness or control, and is fragmented by the cinematography as well as the action. Sex itself is often seen as an anonymous assault of body parts.In the opening piece, Precious, a woman engages in a celebration, lament and mourning of life, love and death. The following three pieces – Scum, Kisses and Shiteater – though maintaining an almost lyrically luscious photographic quality become increasingly provocative and challenging. As hetero and homosexual partners engage in rituals and games of masturbation and defecation, whipping, binding and shaving, sucking, sodomizing and fondling, Hoolboom’s cinema of cruelty turns its attention to the rituals and pastimes of nineties love. The often religious or ceremonial tone of the whole film is accurately offered up in Earle Peach’s consuming score, with musical motifs ranging from devotional to lounge.” Alison Vermee, Vancouver International Festival

“Just when it was beginning to seem that Mike Hoolboom, one of the most prolific and compelling figures on the contemporary Canadian experimental scene, was threatening to become, well, respectable, along comes this, easily Hoolboom’s most uncompromisingly confrontational movie yet. Comprising four luminously shot, sepia-toned vignettes that vividly depict the body as the primary site for moral transgression (which is a polite way of saying that, in this movie, the functions of sex, eating and defecation are displayed in queasy and uncensored proximity to each other)… it’s proof that Hoolboom is not an artist to be comfortably compartmentalized and tucked away yet. Fascinating and distinctive.” Geoff Pevere, Globe and Mail

“House of Pain, the latest offering from prolific experimental helmer Mike Hoolboom, is one of the most extreme, disturbing pics to emerge from Canada’s indie film sector, and the ultra-explicit portrayal of a wide variety of sexual acts, coupled with Hoolboom’s idiosyncratic style, ensures a highly limited theatrical life” Variety, Oct. 16, 1995

“House of Pain is easily the most transgressive film in the program’s history – a virtual litany of fundamental middle-class taboos, many of which involve intercourse and creative things to do with human waste, which are not only depicted but scrupulously scrutinized as the film, which is gorgeously shot by Hoolboom himself, guns its way across every final moral frontier it can find. As strangely poetic and beautiful as it is masochistically confrontational, House of Pain seems determined to push even the most tolerant of viewers to the outer limits, as if to remind us of just how hypocritically bourgeois even the most libertarian among us are.” Geoff Pevere, Globe and Mail

“House of Pain is a wordless psychodrama involving the body, power, mourning and transgression… Provocative and engaging House of Pain is an exploration of the temple we call the body. Conjuring both adoration and aversion it is not for the faint of heart. A black and white dream washed over in many tones, its imagery is starkly visceral, yet stunningly beautiful.” Liz Czach, Toronto International Festival

“Through the House of Pain the Canadian director discovered his 120 days of Sodom. After three years Hoolboom returned to his already finished film in order to think about it once more and redo it (there was too much pain in the house of pain). In the new version, the picture, which is framed by psycho-horror in genre and by critics’ comparisons with the artistic hits of Genet and Pasolini, consists of four parts which are both a praise and a revolt, a synthetically paralyzing survey of all the nooks of the house of pain in which we are staying, an avant-garde anatomy of the human body. The twirls of abomination and bliss require a very tolerant viewer, the hypnotical film without words goes to the very border of what is acceptable, it is another of the films in which ethics are covered by the skin of the sensuous, instinctive, and mortal body, this vessel of excrements, urine, seat and semen. Homosexuality, sado-masochistic sexual practices, the fourth and final part of the film ‘shiteater,’ which definitively breaks the protected zone of what is considered socially unjustifiable. As if the director with the time-bomb of the lethal virus in the body (the code of our death) wanted to show (the film stands mute, it only shows) all the dark and dirty things with which his body struggles, the weight of these glands. All this would not be enough if Hoolboom’s black and white world was not being uplifted by the strange tenderness which balances out the director’s fetishist obsession to give the film something that had never appertained to it – a film is hardly ever intended to be the last movement. The long interrogation of sin pushes the viewer into the defensive, s/he wants to run away from the cinema, for we simply do not want to see certain things; we know about them but being silent about them allows us to survive (or they do not concern us, we are not on the reverse side of the mirror yet). Even for this reason we consider it important to draw the viewer’s attention to the extreme nature of the featured picture… In the fetishist relationship we are inside ourselves, we become a thing which represents a thing, led into the intimacy of an unloving thing and all the time during full consciousness, we succumb to the ecstasy of how the thing – us – is being dealt with. We experience inside and simultaneously we look at ourselves from the outside, we give ourselves to be seen absolutely and at the same time we are perfectly hidden. Uncertainty: to what else can the picture get even closer so that our eyes could bear it, what can represent and own, which parts of the body can vision take out from us and present them in order for us to be able to survive ourselves? Maybe the borderline of what is bearable is defined by the will for life, if it collapses, the safety of the constant forms and the divisible space of the body and soul is lost, the soul becomes the phantom of the thing of the body, its helpless fetish, which succumbs to its violence and wants only to free itself from its ability to perish, sometimes through a prayer, other times through excrements. Both are an appeal to the finality to a metamorphosis within it.” Petr Kubica, Jihlava Festival

“In the fetishist relationship we are inside ourselves, we become a thing which represents a thing, led into the intimacy of an unloving thing and all the time during full consciousness, we succumb to the ecstasy of how the thing—us—is being dealt with. We experience inside and simultaneously we look at ourselves from the outside, we give ourselves to be seen absolutely and at the same time we are perfectly hidden. Uncertainty: to what else can the picture get even closer so that our eyes could bear it, what can represent and own, which parts of the body can vision take out from us and present them in order for us to be able to survive ourselves? Maybe the borderline of what is bearable is defined by the will for life, if it collapses, the safety of the constant forms and the divisible space of the body and soul is lost, the soul becomes the phantom of the thing of the body, its helpless fetish, which succumbs to its violence and wants only to free itself from its ability to perish, sometimes through a prayer, other times through excrements. Both are an appeal to the finality to a metamorphosis within it. Petr Kubica, Jihlava Festival

House of Pain by Laura Marks

Mike Hoolboom’s feature-length film House of Pain (1995) is a suite of stories that turn around abuse, scatology and bizarre manipulations of bodies. In Precious, Kika Thorne plays a woman who fucks the earth in a cemetery, finds a magical eye, and bathes her face in urine. In Scum, a married couple played by Charles Costello and Janieta Eyre use their own shit to play out a dynamic of alienation and self-loathing. In Kisses, Paul Couillard and Ed Johnson enact a game of sexual torture and revenge, ending in a frolic at a playground. And in Shiteater, Andrew Wilson transforms himself into a magical being who, along with other morning rituals, generates a vast amount of (fake) shit and stuffs it into his mouth. Audience members at the premiere screening of House of Pain demanded to know why Hoolboom had made such a shocking, ugly movie. But they also acknowledged its beauty, at least at the level of the film’s richly textured, black-and-white surface.

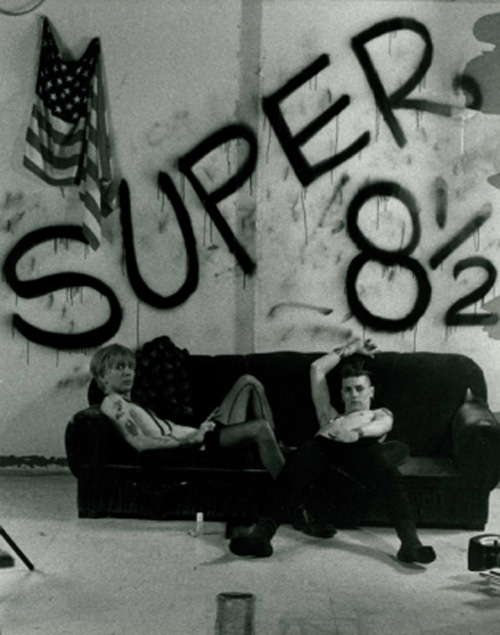

What does it mean that a film that depicts appalling scenes of torture, shit-smearing and the abuse of objects is beautiful? I don’t the ink the shock value of House of Pain is a question of épater le bourgeois, even if such a thing were possible nowadays. For one thing, there is a simplicity to the way the film presents its scatological scenes. This was not the deadpan, can-you-take-this shock value of rather adolescent films like Gregg Araki’s The Doom Generation (1995), Todd Verow’s Frisk (1995), Bruce La Bruce’s Super 8 1/2 (1994) (which succeeds for other reasons) or Rico Martinez’s Glamazon (1993). In House of Pain the simplicity seems more like innocence, the way a child does things before knowing they are supposed to be right or wrong.

The four stories are organized symmetrically. In the two middle films, couples find some sort of catharsis only after wallowing in abjection so extreme that they would to dissolve as separate individuals. The framing films have an air of redemption and peace, and both end with the figure walking on the beach or into the water.

Also, both characters in the outer films use strap-on dildos-stunningly large, smooth, elegant abstractions; in the inner films, fucking is done with real penises that bear no comparison. This seems to be a comment on the insufficiency of representations of masculine sexuality, if not the worlds-apart difference between penis and phallus. Kika Thorne’s ‘angel’ fucks with her strap-on and comes, even generates (she fucks the ground, then finds a magical eye in the hole she has made), with a sex that seems comfortably borrowed, seems to fit her well in House of Pain‘s alternative universe of sexual endowment. The character Andrew Wilson plays transcends his sex: he erupts in other ways, defecating profusely and, with subtle eroticism, breaking a raw egg in his mouth, but like the woman of Precious, he comes only through a dildo.

By contrast, biological male sexuality is punished in House of Pain. In Scum, each member of the estranged couple finds an alternative erotic object. For the woman it’s a bicycle, which she caresses and makes love with, in a tender, visually lyrical scene where the shapes of the bicycle echo the lines of the woman’s moving body. For the man the erotic object is a cauliflower. It is extremely painful to watch him cut a hole in the cauliflower, widen it only a bit with his finger, and painfully fuck its hard interior with his real penis. (The subsequent show will make me skip those dip-filled vegetables at parties from now on.) And in Kisses the engagements between the two men are more like rape or torture. The man played by Couillard undergoes horrible torments, beginning where the camera discovers him sobbing on a seemingly endless pile of concrete rubble, then finding worms and greedily eating them, and continuing to the scenes where the other man tortures him.

Couillard co-wrote this scene with Hoolboom. Not only is Hoolboom willing to devise scenes where male characters can be humiliated (which easily extend to the director himself) but so is Couillard, who plays the most put-upon figure in the film. Perhaps it is at the level of writing that the consensus takes place, the agreement to accept pain and humiliation. It doesn’t happen in the film itself: the woman in Scum violates the man while he is sleeping; the second man in Kisses fucks the first man when he finds him lying unconsciously by the train tracks. These are not depictions of consensual S/M bedroom behaviour; this is not a movie about S/M. The characters break the rules; they represent something out of control.

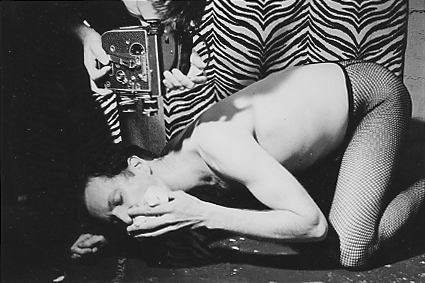

Certainly House of Pain is organized around sexual subjection, domination and transgression. But these seems to be means of expression for something else. The characters sleepwalk through scenes, as through they achieved some state of grace- Hoolboom does call them ‘angels’ in the credits. There’s an experimental, neutral quality to the scene, for example, where the woman of Precious urinates in a pail (and a sculptural fascination with the way the urine sprays from her shaved genitals) or the scene in Scum in which the ‘husband’ smears excrement on his chest. I have to say that this aestheticizing attitude on my part might be a strategy to deal with extreme images. But Hoolboom’s own approach stresses that these images are not there just for their narrative value. House of Pain is an expressionist film, pushing explicit and violent sexual imagery to a certain limit the same way an abstract painter breaks the codes of painting. Hoolboom shot and edited most of the film in a way that works against the eroticism of the sexual scenes, fragmenting and abstracting them. But this style brings another sort of eroticism into the image. There’s a scene in Kisses where the ‘victim’ turns on his aggressor, binds him with wire, and shaves his head: it’s shot in a very dark room, and their struggling figures glow and reflect in the darkness. In Scum there’s a beautiful shot where the ‘wife’ is bathing, and the harsh contrast and high exposure almost solarize the elegant line of her body and her lovely face.

The four stories are too specific to be read as allegories. The scene in Scum does not seem to be an iconic shit-smearing scene, if you can imagine such a thing. The pieces of shit are small and fibrous; when he rubs it on his chest it catches in the hairs. There is too much detail for the scene to remain in the mind as an icon of transgression. Detail complicates an image, polluting it with other ideas, suggesting that to put a simple reading on these scenes would be missing the point. In Kisses, the two men kiss, suck and drink each other through a curtain with a slit in it. The curtain is zebra-patterned. This groovy visual distraction makes me start thinking about why the wall might be zebra, instead of reflecting on the erotics of domination or whatever.

Earle Peach’s soundtrack also forecloses on any sort of iconic quality for the film. In Scum and Kisses the music draws a lot of attention to itself, changing dramatically with each short scene. The music seems to be most successful in Shiteater, where instead of changing every minute it maintains a growling, eerily modulated chord throughout. Like the music, the exaggerated sound effects-the juicy noises of fucking the sloppy sounds of shit, the irritating sound of a zipper being pulled up-perversely underscore the fact that this is a film, an experimental film. Or, again, maybe it’s me who disengages form the film at these points. In my notes taken in the dark screen room, the expert detached criticism gives way to ?ICK!!!? in more than one place. An image that is just bearable to watch becomes unbearable for me when sound is added.

In its search for an intimacy that breaches the body’s boundaries, it’s interesting to compare House of Pain to Frisk, which was also at the Toronto International Festival. Like Dennis Cooper’s novel on which it is based, Frisk takes the rather densely literal approach that the best way to ‘get inside’ another person is to cut them open. It’s like a bad joke on the idea of visceral knowledge. House of Pain seems to be more about finding a state of grace within, or despite, one’s own body, a state that can only be achieved by taking bodies to extremes. The film touches on a deeply sad, inexpressible longing. How can we live inside these bodies? Can our bodies express truth or love? The ordeals the ‘angels’ endure test the limits of self-coherence and the possibility of survival, with love or self-love intact. When at the end of Precious the woman walks into the light on the beach there is a great sense of release, of having purged some demon. I think this feeling of overwhelming longing is the quality that attracts viewers even when we cannot bear the scenes depicted.

Ultimately House of Pain uses the material of film itself to express what it means to get inside another body. The high-contrast film turns everything depicted into an enormous landscape: the elaborate fabrics and laces the woman wears in Precious, for example, become a world of texture that blends with the woman’s own skin and the grass and sand behind her to make an entire consistent skin on the surface of the image. Frequent close-ups and shots in enclosed places also pull the viewer into a place where she cannot distinguish near and far. Hoolboom’s camera (and film stock) have an obsessive desire to bring what is far near, so that the image itself becomes like skin opening onto skin. It is not a voyeuristic kind of looking-at least, the explicit stuff is shot in a way that seems just as interested in shadows and forms as in the actual shit, cocks, etc. – not a desire to subject things to vision, but to dissolve vision in the things erupting before it. House of Pain creates an intimacy that is less like getting inside a body than like turning the film itself into a quivering skin.

House of Pain by Tom Chomont

Very much an original work, defiantly passionate in its own right, Mike Hoolboom’s four-chambered (like the human heart) film, House of Pain, has a clear lineage reaching back to Un Chien Andalou, Jack Smith’s notorious creatures and the early high-contrast works of Franz Zwartjes, as well as the episodic, apocalyptic and poetic prose of Les Chants du Maldoror. And like those works, if not more so, the immersion in body fluids and blurred lines of sexual identity, (symbolic) mutilation (especially the metaphorically charged removal of an eye in two episodes – reminiscent both of the infamous Georges Bataille novel L’Histoire d’Oeil and the Samuel Beckett short metaphor for cinema itself, Film, with Buster Keaton), imagery at once grotesque and erotic that seems calculated to outrage and shock any sense of propriety… and, yes, like those works, if not more so, the overall effect of House of Pain is profoundly spiritual.

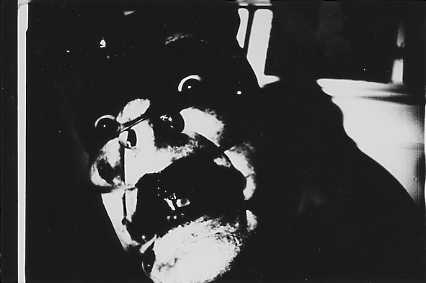

The figures who populate House of Pain‘s rooms and landscapes are ultimately identified (in the closing credits) as Angels and their appearances are surely as awesome as the fearful messengers of Ezekiel and Revelation. They are often surreal apparitions of theatrical artifice, layers of make-up and corsets, petticoats, boots and veils or at the very least given an aura of artifice by the harsh contrast, the expressionistic shadows and wide-angle distortion of the filmmaker’s single-eye vision. In one sense, the detached eyeball represents the camera, and the eyeball planted firmly in the body’s head represents both the filmmaker’s and the viewer’s engaged or impassioned view of the subject of the camera. It is the relation between the two eyes that imbues the image with charged meanings derived from a canny use of film stock, lens distortion, the contrivance of choosing what to place before the camera and the sense of syntax which connects discontinuously filmed images into a whole.

The film begins, in Part 1 Precious, with a lone figure which, while exhibiting a large male member protruding from under its skirts, appears to be female. In Part 4 Shiteater, the film returns to a lone figure, who while applying much make-up and veils, appears to be male. The two middle episodes (Part 2 Scum and Part 3 Kisses) describe two forms of pairing, the first a marriage (male and female separated and united), the second a series of three pairings involving a young man first penetrated by an angel reminiscent of the opening and closing figures (that is to say, aspiring to a terrible androgyny) and then bound and flayed by another man and finally encountering a playmate.

Precious establishes both the body’s obscenity and the body’s spiritual nature. Ethereal light shining directly into the lens and then reflected on water suggests glimpses of divinity at the opening and closing of the episode, but the middle portion describes the angel’s sojourn in a cemetery, lingering over a headstone inscribed ‘Precious.’ The headstone might be taken as a symbol of the fleeting nature of earthly existence as well as the sentimental attachment of the human soul to this transience, but also suggests the more lasting effects of that attachment and its profoundly spiritual nature. The angel confronted with the finality of death produces an enormous erection which it burrows into the earth, while detaching an eyeball which it inserts, and then secretes from its vagina, reinforcing the ancient ritual of rebirth which this opening proposes and which the film at closing completes.

While Precious ends with a hermaphroditic angel absorbed (dissolved) into water reflecting light, Scum begins with a traditionally defined female and male seen in formal wear and descending the steps of a church. This suggests a wedding of man and woman. The man is seen removing his turds from a toilet and smearing himself ecstatically and later the woman wakes and squats over the man’s open mouth filling it with her shit. In intercut images she is seen wearing a bouffant petticoat which somewhat echoes her hairstyle and riding a bicycle through long-shadowed, paved landscapes (calling to mind the man decorated with a hip skirt and collar riding a bicycle in Un Chien Andalou). The underlying ideas here are marriage as unification dissembling into a transaction of material possession, feces being the original material possession apart from the body/self (ie. filthy lucre). In this sense, the generous mouthful bestowed by the bride is her dowry. A sort of unity is accomplished when the woman removes one of the groom’s eyes (like the opening angel) and after baptizing it in urine offers it to him.

Kisses suggests the greatest sense of physical violation but actually emerges as the most tender and childishly playful of the four parts. The protagonist of this episode suggests both a marginal social outsider and the artist as outsider. He is introduced among refuse and debris on the outskirts of an urban landscape, eating from the detritus and earth he is crawling through. A second figure reminiscent of the opening and closing angels, bedecks itself in front of a theatre makeup mirror (a ritual echoed by the angel of Part 4) before coming upon the protagonist lying as though in slumber on a railroad track. After images describing the angel’s rude penetration of the inert protagonist, the protagonist is seen making a spray-paint outline of his body on the ground. This proposes both the creative endeavor as a stepping-back to regard even one’s own presence (as with the detached eye) and as a marker of a lived experience. The body of the protagonist is an unmoving object during the event but comes to life in creating the marking of the event. The ritual nature of the dressing up and initiation are advanced in the next encounter which describes the protagonist tied up and hung by his ankles, then cut open. But when he is let down he is embraced by his torturer tenderly and the film’s function as a negotiator of fantasy and rebirth is underscored. In the final sequence of Kisses, the protagonist encounters a stranger while pissing in the hall of an abandoned and dilapidated industrial/institutional building. Among much menacing approaches between the two men, the protagonist shaves the other’s head with an electric buzzer and the two are intercut romping in a children’s playground. This third part to the film suggests a less apparent androgyny and connects art to the ability to transcend the physical and celebrate the spiritual through it, to reconnect with the childhood trust that allows the spirit to be fluent in speaking through the material world.

The final part, Shiteater, resumes the theme of art and the creative act as a spiritual transformation of physical matter. It reiterates the theme of theatricality (make-up and costume) as a sort of androgyny, but the appliance of simple devices to the face and body take on a suddenly frightening distortion of identity. Feces is again seen as material possession of the other, but the feces itself is here outrageously profuse and baroque and the eating of it is most overtly an exhibitionistic and defiant act. The lone figure in this episode performs a ritual of dressing up before going to the toilet and shits looking the camera sometimes directly in the eye. The episode ends with the angel again returning to water which again and most beautifully reflects bright glows of light.

The artist transforms material including self in order to express the inner spirit, just as the material world is a transient, messy moist and putrid place which also manifests spirit, from which it arises. The film’s title recalls the operation room in which Dr. Moreau transforms animals into humans in Island of Lost Souls and which he calls House of Pain. The title thereby likens the artistic endeavor to render the physical spiritual and the spiritual physical. Both accept and transmogrify the body to the surgical manipulation of the body by the renegade doctor. By exaggerating the nature of physical presence and bodily functioning while rendering it in images which by their heightened contrast and stylized assemblage assert the metaphorical nature of representation, House of Pain is like shock treatment for the sensibilities that prevent us from confronting physical reality in order to appreciate its spiritual nature.

EXPLORATION DE LA SEXUALITÉ DANS LE FILM HOUSE OF PAIN DE MIKE HOOLBOOM Par Samuel Bélisle et Julie Vaillancourt

Travail présenté à Thomas Waugh, Université Concordia Seminar in English Canadian Film: Documentary, Identity and Sexuality, FMST 605D Le 22 novembre 2005

“House of Pain is a “psycho-horror in four parts that simultaneously seems to celebrate and be revolted by that house of pain in which we all reside: the body.” Force est de constater, que la représentation de la sexualité marginale dans le cinéma (commercial) est peu exploitée. Quoiqu’il en soit, certains types ou genres de cinémas s’adonnent davantage à la représentation d’un tel propos. Le réalisateur torontois Mike Hoolboom propose, par le biais du genre expérimental, l’exploration de la sexualité marginale dans son film House of Pain (1995). Utilisant des procédés stylistiques qui «réinventent» le langage cinématographique, une grammaire «fringe», il se lance dans l’exploration de thématiques peu explorées telles; l’onanisme, la transsexualité, la scatophilie, à travers l’hétérosexualité comme l’homosexualité. Avec ce film percutant, à la limite du rébarbatif, Mike Hoolboom nous propose une vision de la sexualité à la fois peu orthodoxe et personnelle.

Né à Toronto en 1949, d’une mère Hollando-Indonisienne et d’un père Hollandais, Mike Hoolboom se passionne pour le cinéma dès son plus jeune âge. Si son enthousiasme pour le septième art devint palpable lorsqu’il réalisa des films en super 8 avec son père, il se concrétisa au niveau académique, lorsque le cinéaste en devenir étudia les arts médiatiques à Oakville Sheridan College de 1980 à 1983. Durant ces années d’études, il réalise trois films, à titre de producteur et réalisateur, soit College, Now, Yours ainsi que Self Portrait With Pipe and Bandaged Ear, tous en 1981. Dès lors, Hoolboom annonçait sa vitesse de croisière; un réalisateur actif et prolifique, possédant aujourd’hui une filmographie des plus impressionnantes. Avec plus de cinquante films et vidéos, il est considéré comme un des cinéastes expérimentaux les plus prolifiques de sa génération. Depuis le début de sa carrière, sa filmographie varie constamment; il enlève certains films de la circulation, en ajoute d’autres, ou il les modifie.

Cinq ans après son premier film, possédant alors huit films à son actif, Hoolboom produit et réalise White Museum en 1986, le film qui établira sa réputation: “Ironically because it’s a film that’s not quite a film. Almost devoid of images, it is 32 minutes of clear leader accompanied by an audio collage comprised of TV ads, pop music and a wry voice-over, which muses about (among other thing) the expense of making movies, the tedium and joy of lining up to see them and the gulf between sound and image and being and nothingness.”

Plusieurs aspects formels et thématiques exploités dans White Museum, se retrouveront dans plusieurs de ses films postérieurs. Bien sûr, l’innovation et l’expérimentation sera au rendez-vous, mais le style filmique particulier du cinéaste venait de naître, ou plutôt de s’exposer au reste du monde?D’ailleurs, à propos des premiers films de Mike Hoolboom, le critique Geoff Pevere dénote que le cinéaste « demonstrated a consuming interest in navigating the outer limits of perception, of language, of self, of mechanical reproduction, of bodily sensation and experience (and most recently, and surprisingly, of the discourse of nationhood) .» Des thèmes qui seront récurrent et constamment exploités dans ses films subséquents.

En 1989, Mike Hoolboom apprend qu’il est séropositif. Dès lors, il semble atteint d’une urgence dans sa création, puisque dans les trois années suivantes (1989 à 1991), il réalisera treize films! Et ce scénario prolifique est encore d’actualité aujourd’hui! Quoiqu’il en soit, sa fascination pour le corps, due à la maladie, devient une thématique proéminente et récurrente dans son ?uvre, comme par exemple, dans From Home (1988), Eat (1989), House of Pain (1995) et Panic Bodies (1998), pour ne nommer que ceux-ci. Il réalisera deux films qui parlent explicitement du sida, soit Frank’s Cock ainsi que Letters from Home, ce dernier étant inspiré d’un discours de Vito Russo, autrefois activiste pour la cause du sida. Si certains films de Hoolboom sont davantage expérimentaux, plusieurs exposent un caractère autobiographique. Le mode confessionnel qu’il engendre, devient particulièrement touchant dans un film comme Panic Bodies (1998), où Mike Hoolboom communique avec sincérité et franchise, ses sentiments au spectateur, face à son diagnostique du sida.

Au cours de sa carrière, le cinéaste recevra plus de trente prix internationaux, incluant le John Spotton Award remis par l’ONF, pour ses films Frank’s Cock (1993) et Letters from Home (1996), prix décerné au meilleur court-métrage canadien, au Festival International du Film de Toronto. Ses films furent présentés dans plus de deux cent festivals à travers le monde et son ?uvre fit récemment l’objet d’une rétrospective à la galerie d’art del’Université York, à Toronto, en 2004. Prolifique, le cinéaste Mike Hoolboom revêt un rôle majeur dans la communauté du cinéma d’avant-garde canadien. De 1988 à 1990, il est le “Fringe film officer” pour le Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Center, où il crée le défunt magazine The Independent Eye. En plus d’avoir publié plusieurs articles dans divers journaux, anthologies et périodiques, il écrit deux livres soit Plague Years: A Life in Underground Movies, en 1998 et Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film in Canada, en 2001. Aussi, il agit à titre de collaborateur et de co-éditeur d’un livre sur l’oeuvre de Philip Hoffman soit, Landscape with Shipwreck : First Person Cinema and the Films of Philip Hoffman, paru en 2001. Pour plusieurs de ses films, il collabore et co-réalise avec d’importants artistes canadiens de la vidéo et du cinéma expérimental, tels que Kika Thorne (Two, 1990), Steve Sanguedolce (Mexico, 1992), Ann-Marie Fleming (Man, 1991, The New Man, 1992) et Shawn Chapelle (Shooting Blanks, 1995). En 1989, Hoolboom crée le groupe Pleasure Dome, avec Jonathan Pollard, Barbara Sternberg, Philip Hoffman et Gary Popovich. Cette année, le Pleasure Dome célèbre son seizième anniversaire d’exposition, en continuant sa mission envers les artisans du cinéma et la vidéo expérimentale; à priori, le collectif Torontois voulait créer un lieu d’exposition, dédié au films et vidéos du mouvement «Fringe».

Le terme «Fringe» signifie en français : la marge, la frange, lorsqu’on parle d’une partie plus ou moins marginale d’un groupe de personnes. Le terme «Fringe» fait également référence à la culture underground . Utilisé à partir de la fin de la deuxième Guerre Mondial à Édimbourg, le terme «Fringe» fait référence à un type de théâtre de rue. Alors qu’un festival de théâtre très prestigieux avait été instauré pour redonner une certaine perspective artistique et culturelle à l’environnement social de l’après-guerre, certains artistes se sont vus exclus du festival d’Édimbourg et ont donc décidés de présenter leurs ?uvres en marge de ce grand festival. Ainsi était créé le festival «Fringe» d’Édimbourg. Depuis, les événements «Fringe» se sont multipliés à travers le monde. La première manifestation d’un festival «Fringe» au Canada s’est produite à Edmonton en 1982. Montréal a également son festival «Fringe» depuis 1990.

Évidement, le terme «Fringe» ne se limite pas seulement au théâtre mais peut s’appliquer à tous les médiums artistique, autant la peinture, lamusique et bien sûr le cinéma. Le style «Fringe» est avant tout une forme d’art qui se trouve évidemment hors du mainstream. Il se caractérise comme une forme d’art peu coûteuse, qui se rapproche des traditions de l’art expérimentale et qui est souvent difficile d’accès. Mais c’est surtout un type d’art très subjectif et, par conséquent, où l’artiste est situé premier niveau de sa création. Pour Mike Hoolboom la relation entre son film House of Pain et l’art «Fringe» est évidente: “about fringe movies and the house of pain, sure house of pain is a fringe film, difficult to see, nearly impossible really because it requires a 16mm projector which few places have and the money to rent one of the only prints available. It depicts a marginal sexuality, a marginal lifestyle, and is available in a marginal way. it was made of course with very little money and home made everything (costumes, sets, props, etc.) the fringe imagines that it is necessary to change the way something is shown (the grammar of showing) as well as what is shown (the ‘content’) (as if the two can ever really be divided). The fringe, or part of the fringe, imagines that by changing the grammar, we can say and see different things, have different kinds of experience, different kinds of pleasure for instance.”

Effectivement, le visionnement du film House of Pain nous procure certainement un autre type d’expérience, un autre type de plaisir. Le film est très difficile d’accès, voir, à la limite, rébarbatif dans les sujets qu’il aborde. House of Pain fut réalisé en 1995 et durait à l’origine 90 minutes lorsque Hoolboom l’a présenté au Festival International du Film de Toronto. Par la suite, le film a été coupé de dix minutes pour les projections en salle qui suivirent, puisque le réalisateur canadien trouvait son film trop long. Quelques années plus tard, Mike Hoolboom a retravaillé son film, en coupant et en ajoutant quelques scènes, pour aboutir à une version de 50 minutes et c’est cette version qui est aujourd’hui distribuée.

Tourné en noir et blanc et imprimé sur pellicule couleur, House of Pain revêt un caractère très poétique de par sa teinte sépia. Le long-métrage ne contient aucun dialogue et est divisé en quatre tableaux: Precious (1994), Scum, Kisses et Shiteater (1993). On remarque aisément dans cette oeuvre de Mike Hoolboom des influences du cinéma expérimental, du cinéma de Méliès, du surréalisme et finalement du cinéma d’avant-garde. D’ailleurs, certaines séquences font vaguement penser au travail de Maya Deren dans Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) par le traitement de l’image et l’atmosphère qui s’en dégage. House of Pain met en scène des amis du réalisateur dont la réalisatrice Kika Thorne ainsi que Janieta Eyre, Charles Costello, Andrew Wilson, Paul Couillard et Ed Johnson.

Le titre du film fait référence à l’Île du Dr. Moreau comme le souligne Tom Chomont dans Plague Years: «The film’s title recalls the operating room in which Dr. Moreau transforms animals into humans in Island of the Souls which he called “The house of pain”. The title suggests that the artistic endeavour, like the role of the body, is to render the physical spiritual and the spiritual physical.»

Le film de Mike Hoolboom est très difficile à résumer et à interpréter parce qu’il est très symbolique et très subjectif. Les thèmes importants qui transpirent de l’oeuvre sont évidemment les thèmes du corps, de la mort, de l’onanisme, la transsexualité, le travestisme, la purification, les rituels, l’institution religieuse, le couple, les genres masculin/féminin, l’hétérosexualité et l’homosexualité, le sadomasochisme, les tendances scatophiles, la zoophilie et l’urbanisme. Ainsi, Hoolboom met en scène une symphonie de l’horreur où le corps humain, sous le scalpel du réalisateur torontois, dévoile sa souffrance. Mike Hoolboom affirmera d’ailleurs dans un article pour la Pacific Cinematheque of Vancouver: «There was too much pain in the House of Pain.»

D’entrée de jeu, la marginalité du discours de Mike Hoolboom nous surprend fortement. Le film aborde la question de la sexualité hors norme, voir «Fringe», de façon complexe. La sexualité et ses thèmes connexes, tels que le corps et la maladie, dirigent en quelque sorte la trame narrative de House of Pain . Dans le premier tableau, Precious, Hoolboom nous propose un personnage dont la transsexualité devient un état instable, où l’acte sexuel représente la libération. Jack Rusholme, dans un article électronique consacré au cinéma expérimental de Mike Hoolboom, décrit cettepremière partie de la façon suivante:

«A first-person chronicle of loss and remembrance, Precious features Toronto filmmaker Kika Thorne in a graveside visitation, there to conjure memories of her lost eye. Staged in three parts, her eye journeys through the body, until a ritual compact with the dead is achieved.»

Alors, dans ce premier tableau, Mike Hoolboom nous présente un personnage féminin qui évolue de façon fantomatique à travers les pierres tombales d’un cimetière. Celle-ci aboutie sur une tombe où l’ont voit l’inscription «Precious». L’atmosphère du film et l’aspect fantomatique du personnage à la longue robe blanche et chevelure blonde, soutient l’idée de la mort, de l’immanence et de la transcendance, représentée, entre autre, par les cercles lumineux que l’ont voit apparaître à trois reprise dans ce tableau. On remarque à cet instant que le personnage est amputé d’un il, l’organe de la vue. Cet il perdu, en référence au châtiment d’?dipe et au complexe réutilisé par Freud, sera retrouvé grâce à l’activation des pulsions sexuelles. En effet, la performance de l’onanisme sur la tombe de «Precious» n’active pas seulement le plaisir physique, mais également le resurgissement de la perte, en l’occurrence, la perte de l’oeil. À la fois ange et corps, notre personnage est retenu sur terre à cause de l’aveuglement. L’accomplissement du coït permet à notre personnage de retrouver cet objet si précieux, son il manquant. La question de l’identité sexuelle est quelque peu nébuleuse dans ce premier tableau. Effectivement, le personnage féminin soulève sa robe pour dévoiler un pénis. La transsexualité vient ainsi illustrer l’ambivalence de la situation, de l’état du corps, entre deux corps, tout en critiquant la définition des genres masculin/féminin. Il est également intéressant de remarquer que le phallus est en plastique, symbole de la matérialité, matière industriel, jouet sexuel, le godemiché est l’objet parfait de la critique de l’importance du commerce du sexe dans notre société. Cet organe en plastique représente le lien entre la terre et le corps qui, dans cette relation sexuelle sur la tombe, lui permettra de retrouver l’il dans le sillon créé par le phallus. Ce phallus s’est nécrosé après le coït et notre personnage s’en débarrassera en le cassant en deux avec ses dents. Dans cette scène aux allures gothiques, la sexualité permet de régénérer cet il arraché au corps. Le corps désormais sexué retrouve alors sa plénitude, son unité, et l’?il en est le symbole. D’abord, la femme avalera l’organe retrouvé et ensuite, le fera pénétrer dans son sexe. Cette intériorisation de l’il, pouvant représenter la conscience, soulève la question de la transcendance. D’ailleurs, Mike Hoolboom, à cet effet, utilise une certaine progression au niveau de la surexposition de la pellicule. Le film devient de plus en plus blanc, gommant à quelque reprise la silhouette du personnage qui s’effacera dans le cadre. Le corps s’élève, il n’est plus cette bête de chair rattachée à la terre. Les déchets honteux deviennent, par le fait même, purificateurs. La femme se lance dans un rituel de purification, où elle se lave le visage avec son urine, ce qui lui permet de disparaître dans ce désert blanc, à la toute fin du premier tableau, représentant la mort. Il est intéressant de faire un parallèle avec le sida, la maladie transmise sexuellement la plus mortelle, qui retient le malade dans des limbes terrestres, corps pas tout à fait vivant mais pas déjà mort. Le remède serait peut-être un changement de vision selon le discours de Mike Hoolboom.

La sexualité chez Hoolboom prend des connotations sociales très importantes. Le deuxième tableau, intitulé Scum, met en scène un couple hétérosexuel. En fait, ici, l’entité du couple dévoile toutes ces facettes au spectateur à travers les rituels du mariage et de la vie de couple, entre autre, dont la sexualité semble être le moteur. Les relations homme/femme ainsi que la définition des genres masculin/féminin sont les principaux thèmes interrogés par le réalisateur dans cette deuxième partie, tout en préservant également un discours sur le matérialisme. Beaucoup d’objets revêtent une grande importance, par exemple, le miroir, la bicyclette, le chou-fleur, la cage. Tous ces éléments sont réunis dans une mécanique du rituel entre les deux époux. Le premier rituel abordé par Hoolboom met au premier plan la question de l’image. D’abord, la femme quitte le lit conjugal pour se maquiller. Ce rituel de beauté critique l’utilisation de cet apparat illusoire de la femme qui tente de tromper l’homme pour séduire. Cette question d’illusion, Mike Hoolboom parvient à l’illustrer en utilisant un miroir déformé par une substance visqueuse. L’image de la femme devient ainsi trouble, voire même monstrueuse. Il est intéressant de remarquer que le miroir est l’objet qui unit les deux protagonistes, objet de la mémoire de leur reflet, entre autre grâce au miroir de poche qu’ils s’échangent tout au long du tableau. D’autre part, ce rituel vient caractériser le personnage de la femme jusqu’à influencer la performance de l’actrice qui ne revêtira aucune expression faciale, figeant le personnage de la femme dans un état d’objectivation, la femme devient alors image.

Un autre aspect intéressant proposé par Mike Hoolboom dans cette séquence est évidement le travail sur l’affect du spectateur. La femme s’enduit les lèvres d’un rouge à lèvre dont l’aspect visqueux et luisant est plutôt repoussant. En effet, House of Pain joue beaucoup sur la création d’affect chez le spectateur. Par des qualités filmiques visuelles et sonores, Hoolboom réussit à faire surgir chez le spectateur le souvenir d’expériences sensitives qui sont généralement repoussantes, dégoûtantes. Le réalisateur arrive à créer chez le spectateur des expériences sensorielles, voire même olfactives, grâce à des textures visuelles, des sons, auxquelles le spectateur identifie une odeur, un goût. De cette façon, Hoolboom va jusqu’à faire intervenir le corps du spectateur à l’intérieur du film. Effectivement, cette expérience est très claire lorsque Hoolboom aborde le thème du rituel scatophile lorsque la femme s’accroupit et défèque dans la bouche de l’homme qui dort. Cette scène est décrite de la façon suivante par Tom Chomont: «The underlying ideas here are marriage as unification dissembling into a transaction of material possession, feces being the original material possession apart from the body/self (filthy lucre) .» En effet, la question de pouvoir est très intéressante en relation avec le thème de la sexualité. Après avoir joué le jeu de la séduction, la femme défèque dans la bouche de l’homme pendant que celui-ci est inconscient. La position de la femme lors de l’acte lui donne une certaine supériorité face à l’homme dans cette relation plutôt marginale. Ce geste est d’ailleurs difficile à interpréter. En fait, la femme semble vouloir, grâce à cette transmission de matière, soumettre l’homme à son charme. L’homme, plus tard, complètera ce rituel scatophile en s’enduisant de sa propre merde, en la mangeant, dans le but de faire ressurgir le goût de la femme, également représenté par la découverte du miroir de poche à l’intérieur de la cuvette sale. Cette scène soulève ainsi, par l’échange de matière corporelle, une certaine dominance sexuelle, inversant les rôles de notre société patriarcale, et en donnant le pouvoir à la femme. Par la suite, le rituel sexuel prend le visage de la masturbation alors que chacun des personnages se lancent dans des expériences onanistes et masochistes. De son côté, la femme vit une expérience érotique avec sa bicyclette, symbole mécanique aux formes à la fois phalliques (guidons, selle) et très féminin (les courbes de la roue). Loin d’être agréable, la scène est tout de même extrêmement sensuelle. L’homme, quant à lui, se masturbe dans un chou-fleur qu’il découpe d’abord à l’aide d’une lame et pénètre ensuite. À noter qu’il revêt un masque chirurgical qui semble l’empêcher de crier. C’est en quelque sorte une façon pour l’homme de prouver sa masculinité, alors que ce dernier revêt des allures à la fois de barbare et de super héros alors qu’il fait apparaître l’objet du plaisir. Toutefois, l’identité sexuelle est quelque peu ambivalente puisque l’homme porte un sous-vêtement féminin. Finalement, il avalera la mixture blanchâtre qui suinte du légume, le sperme, symbole de la fécondité. Ainsi, il n’y pas de perte. Effectivement, la masturbation a longtemps été réprimée par la société victorienne et la religion catholique puisqu’elle ne permettait la fécondation et venait mettre en danger le couple hétérosexuel ainsi que la sexualité de l’enfant tel que présenté par Michel Foucault dans l’«Histoire de la sexualité». D’ailleurs, Gayle Rubin soutient ce fait dans son essai Thinking Sex: «The idea that masturbation is an unhealthy practice is part of that heritage.» Rubin classifie ainsi la masturbation dans une classe incertaine entre une sexualité normale, illustrée par le couple hétérosexuel, marié, monogame et reproductif, et une mauvaise sexualité, comprenant entre autre le fétichisme et le sadomasochisme. Mike Hoolboom reprend alors la question de purification, le corps doit être lavé. On remarque dans la séquence où la femme prend un bain que celle-ci urine dans l’eau et se lave avec cette eau. Encore une fois, l’urine est ici symbole de purification, tout comme dans le premier tableau. Mike Hoolboom utilise dans cette séquence une légère surexposition donnant un caractère laiteux à la peau de la femme et à l’image, attribuant une certaine pureté à l’atmosphère. Mais on peut également percevoir l’urine comme un symbole de bestialité, si on pense par exemple aux phéromones que certains animaux sécrètent pour attirer un membre de la même espèce. La femme, quant à elle s’asperge de son urine pour attirer l’homme. La séquence qui suit est intéressante au niveau symbolique. On retrouve l’?il de la première partie, Precious, que la femme arrache à l’homme, ce qui semble retirer l’essence barbare de ce dernier, qui disparaît laissant place à une cage où se trouve le chou-fleur. La femme, en possession de l’organe de la vue de son conjoint, rempli le troue créé dans le légume par le phallus dans la scène précédente. L’homme réapparaît, vêtu d’une robe blanche. À ce moment, le couple peut s’unir dans l’acte sexuel où la femme domine toujours. On perçoit ainsi une certaine progression à travers ce deuxième tableau, comme si chaque individu devait franchir différents niveaux, certaines épreuves, directement relier à la sexualité, au corps. Comme s’ils devaient voyager à travers certaines expériences underground , visiter des sexualités incertaines, voire anormales, telles que la scatophillie, la masturbation, le masochisme, avant de subir une purification et d’atteindre l’unification du couple. Mike Hoolboom décrit ce deuxième tableau de la façon suivante: “Scum shows how things are more likely to occur, both partners uncovering the worst in themselves, exploring the dark side, and when they’re right at the bottom they look up and see the other covered in shit and horror and say, okay, I can live with that. It’s only then they come together and kiss.”

Ainsi, débute le troisième tableau du film House of Pain. Avec Kisses, Mike Hoolboom continue son exploration de la sexualité, mais en mettant en scène les problématiques reliées à l’homosexualité et comme le souligne le cinéaste: «Kisses shows two men who behave like many lifetime partners, relying on masquerade and game playing to hold it together. They beat, torture, and shave each other, finally winding up in a playground, just two big kids out for a laugh.» Ainsi, la thématique principale de cette partie du film est sans contredit l’homosexualité et toutes les pratiques sexuelles associées à la culture gai. La version de 80 minutes proposait une entrée de jeu différente de celle présentée dans la version de 50 minutes. La ville de Toronto et donc le sous thème de l’urbanisme, occupait une place prépondérante en début de tableau. Une présence physique et sonore, qui renforçait cette idée de symphonie urbaine, associé aux city films. On pouvait y retrouver : autoroutes, chemins de fer, trains, un drapeau canadien. Ceci, dit la tour du CN, qui est non seulement une mise en contexte, mais aussi un symbole phallique évident et l’escapade dans un parc en fin de tableau, demeure dans la version de 50 minutes. Si dans la version antérieure de House of Pain, nous proposait une mise en contexte aussi importante, ce n’était pas à tout hasard. En effet, elle servait le propos du «sexe de rue», grandement associé à la culture gai. Une des premières scènes (dans la version de 80 minutes) nous présentait un homme pratiquant le travestisme, autre thématique largement associé aux pratiques homosexuelles et identitaires. Cet homme, partait à la «chasse à l’homme» (les deux chiens renforcent cette métaphore), puis trouvait un homme dans la rue pour le sodomiser. Autre référence au milieu gai, non seulement dans l’acte sexuel, mais aussi dans cette façon rapide de rencontrer et d’assouvir un besoin. Ensuite, l’homme sodomisé se réveillait, traçait le contour de son corps (à la manière des scènes de crime), puis s’y couchait pour feindre la mort. Symboliquement, cette scène fait référence au sexe de rue non protégé et par surcroît aux maladies mortelles, transmissible sexuellement, voire le sida, fréquemment (et malheureusement encore trop souvent!) associé à la culture gai.

Ceci dit, ces quelques scènes n’ont pas survécu au nouveau découpage de Hoolboom, dans la version de 50 minutes, version qui selon le réalisateur se voulait, «plus courte, resserrée, économique et moins langoureuse». Ainsi, cette version débute (où se continuait la précédente), soit dans cette scène où un homme embrasse et caresse langues et pénis à travers un mur. L’homme avale le sperme et dans la scène suivante l’urine de son partenaire, telle une fontaine de jouvence, mettant en scène l’ urophilia (un paraphilia, terme grecque signifiant au-delà de la normalité). Précisément, cette pratique sexuelle, ce plaisir de boire l’urine de son partenaire fait référence au «Golden Showers» ou aux «Water sports», euphémismes pour l’ urophilia. De plus, le fait que cet homme procure des plaisirs sexuels à des hommes dont il ne voit pas le visage, ni le reste du corps et donc juste les organes sexuels, renvoie à un anonymat sexuel nonchalant et au sexe anonyme non protégé, notions fréquentes dans la culture gai. D’abord, le fait d’avoir des relations sexuelles non protégées, revoie symboliquement au sida. Ensuite, cet anonymat sexuel symbolise et mets en scène (de façon stylisée bien sûr, mais ô combien imaginative!) aux Glory Holes. Par définition, «a glory hole is generally defined as a small fist-sized hole between private video booths in an adult bookstore. It is placed about hip high for the average guy and is just large enough to place a man’s penis through to let the person on the other side perform whatever sexual activity he pleases on it.» Dans la communauté gaie, les Glory Holes sont plus que des légendes urbaines, puisque ces pratiques sexuelles sont fréquemment pratiquées, que ce soit dans certains bars ou saunas, par exemple.

Dans les scènes suivantes du tableau Kisses, diverses pratiques sexuelles sont abordées. Entre autre, le sadomasochisme, lorsqu’un homme attache son partenaire par les pieds, pour lui infliger des blessures corporelles, à l’aide d’une lame de rasoir. La présence de rituels est prédominante; avant de couper son partenaire et d’entamer sa relation sexuelle avec lui, le dominant, le lave méticuleusement, tel un rituel. La surimpression des mains et des visages, après la relation, pourrait non seulement symboliser les hallucinations du dominé, mais aussi une certaine transe et une renaissance, puisqu’après sa relation, il se lève immédiatement, sans blessure apparente.

Pour conclure ce tableau, Hoolboom situe l’action dans un parc de Toronto. Les deux hommes s’y amusent comme des gamins, dans les jeux, le sable, les fontaines d’eau et pataugeoires publiques, sur fond de musique joyeuse. D’ailleurs, la présence de l’eau dans ce tableau, comme dans tout le film, est grandement exploitée (aussi ils prennent une douche ensemble) et semble symboliser la renaissance, la purification. Finalement, les deux hommes s’embrassent. Une telle fin, remplie de positivisme, pourrait venir souligner une vie homosexuelle, qui n’est pas uniquement basée sur le sexe, où les partenaires en viennent à vivre une vie harmonieuse en communauté, malgré leurs pratiques sexuelles marginales.

Dans le quatrième et dernier tableau de House of Pain, Mike Hoolboom atteint l’apogée des pratiques sexuelles marginales, en mettant en scène des actes scatophiles. Dans son livre Plagues Years: A Life in Underground Movies, Hoolboom commente:

Like the human heart, House of Pain has four chambers. Shiteater is the last. It shows a man waking, dumping, and eating. Then he dresses in threads copped from medieval plague doctors who dared to enter cities locked in quarantine. Equal parts showboat, religious mystic, and scientist they dressed in bird costumes and performed rituals to heal the sick. When they didn’t die themselves. Finishing his dress-up our man begins to play with his body, taking and egg out of his mouth, opening up his underwear to find a rooster, which turns into a cock. He comes.

Dans ce dernier tableau, les thématiques explorées tout au long du film, sont récurrentes. La présence de la religion et de l’église est soulignée, de par la musique ecclésiastique; cette association constante de la sexualité et de la religion/église tout au long de House of Pain, renforce cet idée de péché religieux, associé à la sexualité marginale (et à la sexualité tout court). La grande présence de rituels, est aussi prépondérante. Avant de procéder à ses actes scatophiles, le shiteater, se lave les mains dans un petit bol (qui rappel le bénitier), se rase, se maquille, s’habille en robe, se mets un nez de cochon. Bref, tout un rituel accompagne le travestissement de sa personnalité, qui devient un déguisement grotesque. L’acte scatophile du shiteater devient presque une performance; la scène devient théâtrale et claustrophobique. D’ailleurs, l’aspect effiloché de ses excréments, pourrait symboliser et/ou représenter des pellicules de film, métaphore de la société de consommation, du cinéma commercial. Le shiteater devient un produit de la société de consommation; il devient le créateur et le consommateur de sa propre nourriture.

On ne peut nier la présence étrange de ce coq, qui semble devenir un objet d’excitation sexuelle et donc un lien évident avec la zoophilie; le shiteater se déguise en oiseau, sort un oeuf de ses parties génitales, caresse le coq qui devient un pénis, se masturbe, puis éjacule. Aussi, la présence de l’eau, comme moyen de purification est encore très présente dans ce tableau, puisque après ses actes scatophiles, le shiteater va se laver, s’immerger dans le lac. Il en ressort nu, ce qui est certainement un clin-d’?il à la religion, aux rituels et finalement au baptême. D’ailleurs, l’interprétation de Hoolboom à propos de cette scène, va dans ce sens:

The film closes in the ocean where he strips and emerges naked. Reborn. The shiteating describes the circle of himself Dante spoke about. In his solitude, the body’s become a world of play. He’s become his own food, both factory and consumer. He sails to the end of this world where he is baptized into a new one. Ready to begin again.

Quant l’on procède à l’analyse d’un film comme House of Pain , on peut certainement lier cet ?uvre cinématographique au processus de «disidentification» exposé par José Muñoz dans son texte Performing Disidentification.

Disidentification is about recycling and rethinking encoded meaning. (The process of disidentification scrambles and reconstructs the encoded message of a cultural text in a fashion that both exposes the encoded message’s universalizing and exclusionary machinations and recircuits its workings to account for, include, and empower minority identities and identifications .

De par les procédés stylistiques utilisés, une grammaire «fringe» à saveur expérimentale, House of Pain reconstruit et propose un langage cinématographique hors du commun pour ainsi mettre en scène une sexualité marginale. Cette tactique crée une «disidentification» qui donne un certain pouvoir aux minorités identitaires, voire sexuelles, comme le propose Muñoz. En touchant des sujets tabous et en les exposant dans une grammaire «réinventée», Hoolboom se dissocie du cinéma commercial, de la culture dominante et comme le note José Muñoz : «This mode of reading resist, demystifies, and deconstructs the universalizing ruse of the dominant culture. Meanings are unpacked in an effort to dismantle dominant codes . » Ainsi, une exploration de la sexualité marginale et de ses différentes pratiques est rendue possible. Mike Hoolboom détourne les conventions grammaticales, déconstruit les codes dominants du langage cinématographique, pour nous offrir un film qui illustre brillement son propos.

En somme, on ne peut nier l’apport d’un cinéaste comme Mike Hoolboom, au niveau de la cinématographie canadienne et du cinéma expérimental. En plus de sa filmographie impressionnante, le réalisateur a contribué grandement au niveau de la théorie et du mouvement «fringe». La thématique de la sexualité dans House of Pain est prépondérante et représentée sous diverses formes. À travers les quatre tableaux, les thèmes du rituel, la maladie, le corps prennent des visages à la fois grotesques et poétiques. Ce paradoxe se retrouve dépeint dans diversespratiques sexuelles, qui amène le spectateur à réfléchir sur sa propre identité. Dommage qu’un tel film, qui pose autant de questions, de réflexions, à la fois identitaires et sexuelles, soit si peu accessible. Cependant deux questions subsistent : Ce problème d’accessibilité est-il uniquement relié aux contraintes de l’industrie cinématographique? Le public est-il prêt à encaisser une représentation aussi marginale de la sexualité au grand écran?

BIBLIOGRAPHIE

HOOLBOOM, Mike. Plague Years: A life in Underground Movies, Editor: Steve Reinke, YYZ Books Publication, 1998, 209 p.

José MUNOZ, «Introduction: Performing Disidentifications» dans Disidentifications : Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press , 1999, pp.1-34.

RUBIN, Gayle. «Thinking Sex: Notes for Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality», dans Carole S. Vance, ed., Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality, London , Pandora, 1984, pp. 267-320.

Sources Internet

McBRIDE, Jason. «Mike Hoolboom» dans The Film Reference Library , www.filmreferencelibrary.ca

RUSHOLME, Jack. MESH: How to Die: The Films of Mike Hoolboom http://www.experimenta.org/mesh/mesh04/4rus.html

«Mike Hoolboom’s House of Pain », Pacific Cinematheque de Vancouver, http://www.cinematheque.bc.ca/archives/fcdnso982.html

Ste-Ambroise Fringe Montréal: International Fringe Festival: www.montrealfringe.ca .

Pleasure Dome website ( www.pdome.org/ )

www.bigeye.com/sexeducation/index.html www.sexuality.org

«Mike Hoolboom’s House of Pain » Pacific Cinematheque de Vancouver

http://www.cinematheque.bc.ca/archives/fcdnso982.html Jason McBRIDE, The Film Reference Library ( http://www.filmreferencelibrary.ca ).

Geoff PEVERE, cité par Jason McBRIDE dans, op.cit.

Ste-Ambroise Fringe Montréal: International Fringe Festival: www.montrealfringe.ca.

Mike HOOLBOOM, Plague Years: A life in Underground Movies , Editor: Steve Reinke, YYZ Books Publication, 1998, p. 199.

«Mike Hoolboom’s House of Pain », Pacific Cinematheque de Vancouver, op.cit.

Jack RUSHOLME, MESH: How to Die: The Films of Mike Hoolboom http://www.experimenta.org/mesh/mesh04/4rus.html

Mike HOOLBOOM, op.cit,

Gayle RUBIN, «Thinking Sex: Notes for Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality», in Carole S. Vance, ed., Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality , London , Pandora, 1984, p.268

Mike HOOLBOOM, op.cit,

Loc.cit.

Source électronique:www.sexuality.org

Mike HOOLBOOM, op.cit, p.150.

Ibidem, p.152.

José MUNOZ, «Introduction: Performing Disidentifications» dans Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press , 1999, p.31.

Ibidem, p.26p.152.p. 198.