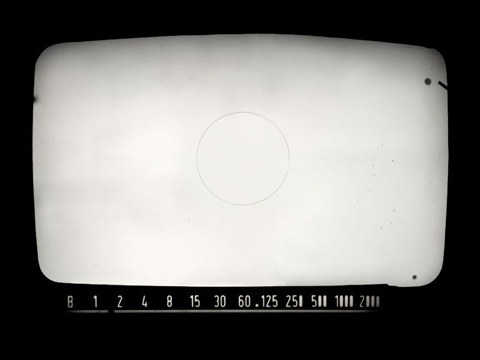

“Ironically, it was the 1986 White Museum (32 minutes, 16 mm, 1986) that established his reputation. ‘Ironically’ because it’s a film that’s not quite a film. Almost devoid of images, it is 32 minutes of clear leader accompanied by an audio collage comprised of TV ads, pop music and a wry voice-over, which muses about (among other thing) the expense of making movies, the tedium and joy of lining up to see them and the gulf between sound and image and being and nothingness”: The cinematic equivalent of flipping the bird, White Museum is an audacious and often hilarious early effort by master provocateur Mike Hoolboom. Viewers must wait about thirty minutes to see the one and only image in the film. In the meantime, Hoolboom expounds on everything from old lovers to making movies to living in the big city. With unabashed irony, he argues for a cinema without images, while simultaneously describing the images he would show if he had the cash. For a film that appears on the surface to be literally about nothing, White Museum becomes a veritable cornucopia of semiotic jokes and meanings, as well as a rich statement on the nature of cinema itself.” (Jason McBride, Canadian Film Encyclopedia)

“Drawing on sources from Warhol to Derrida, the voice-over monologue is an entertaining and thoughtful commentary on the aural component of cinema, on language, movie-watching and production economics. The visual poverty of White Museum is, paradoxically, the means by which Hoolboom creates a powerful analysis of the cinematic image.” (Katie Russell, Now Magazine)

“Taking Snow’s conceptual rigour to another level, Mike Hoolboom’s Guy Debord and Warhol inspired White Museum is a virtually imageless and infinitely witty meditation on cinema.” André Picard

“Equally personal, if more confrontational and philosophical, is Mike Hoolboom’s White Museum, which confounds our cinematic expectations with a white screen overlaid with first person ruminations. Hoolboom in fact only gives us one image to look at but his narration forces us to confront the experience of cinema in a highly stimulating manner.” (Geoff Pevere, Festival of Festivals Catalogue)

“White Museum is a 35 minute audio piece with 33 minutes of clear leader tape. In some hands, that could mean a fatal tour into the land of self-indulgence, but Hoolboom manages to make of his cinema without images an engaging, squatter’s eye view of the critical landscape. Hoolboom’s anecdotal voice-over floats over a soundtrack collage of pop-culture effluvia, television ads and snippets of rock music. His musings on film, the word, and the work-load of trees often resemble a cerebral stand-up routine, built on the conviction that the best thing to do when someone floats a critical balloon is to have a hat-pin ready. Early in the film, he apologizes for the visual tedium (“I just don’t have enough money for the images” ) and mulls over ad hoc ways of alleviating it. Actually, he did find the money to make one image, he says”and I’m saving it for later.

Waiting for the image becomes part of the experience of watching (or not watching) White Museum. Mixed in with Hoolboom’s comic asides are the more sober utterances of his own critical gods: Barthes, Derrida, Godard and (perhaps most significantly) Borges. For Hoolboom, the place to look for the most potent magic of cinema lies at the threshold of sight, just before the image is reached. He rhapsodizes the blank leader tape, and even the experience of lining up outside the movie theatre. “Never getting in is the most exciting,” he decides. After that, waiting to get in is the most exciting… The film ultimately vaults well beyond the level of audio-visual scrapbook in the closing image: a slow-zooming shot of the sun shining through a stand of trees. The deeply moving, magisterial effect of this simple image owes as much to Hoolboom’s careful preparations as to Mozart’s accompanying Kyrie.” (Robert Everett Green, Globe and Mail)

The White Museum by Sarita Choudhoury

He recalls an exhibit of Renaissance picture frames at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich. The frames were empty, hung against white walls… He sensed that the museum had now become the frame of frames. And the frame of the museum? Finally, of course, the universe! (Hassan)

If, as postmodernists envisage, the apocalypse is now, then the film White Museum has cast the filmic bomb. With its post-apocalyptic vision of pure whiteness, the film is nihilistic in its eradication of visual form: it begins and continues for the majority of its duration as an imageless screen. Amidst its white void there is projected a voice, a bodiless voice dispersed in the post-apocalyptic white screen cloud. This dismembered and imageless voice confirms the film’s anti-form, its anti-realism, anti-modernism and finally its anti-filmic form. In its dis-membered state the filmic image/body is killed off, but the filmic voice continues to enunciate, like the mythical figure of Orpheus whose body was dismembered but whose voice remains intact.

The film takes the theme of ‘erasure’ to an intriguing extreme. It remains faithful to erasure’s double intention: both employing and critiquing a medium undergoing analysis. Deconstructing filmic traditions, it employs the film medium while subjecting the images to erasure. Akin to Mallarmé’s publication of a book without words, White Museum‘s imageless screen is terroristic in its operation of erasure, leaving no trace of the old image behind. White Museum‘s blank, empty screen re-sounds the hollow metaphysical scene, one whose mythical constructs can never be traced back to their origins and whose myths are so culturally engrained “They are inscribed in white ink.” It parodies the system’s white mythology whose order and rule have been emptied and unstaged, abandoned and displaced.

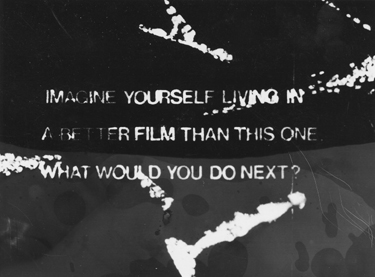

Having effaced its visuals and leaving behind commonly understood notions of ‘film,’ White Museum develops a discursive playing the absence of the image. The ‘play’ consists of the narrator’s commentary, the personal play of a disembodied voice. The extra diegetic voice is different from the typical filmic one which is commonly saturated with didactic, authoritative and patriarchal overtones. In its address to the audience, this Orphean voice elicits the postmodern tendency of participation, of art as performance. The postmodern text, verbal or nonverbal, invites performance: it wants to be written, re-vised, answered, acted out. (Hassan) This invitation to participate signals an acknowledgment of the text as one which is re-read and hence re-written by each subsequent reader. In the absence of filmic images, the audience is encouraged to provide their own for a voice lost in an empty screen, in a white museum.

White Museum is a participatory, postmodern event which ruptures status quo separations between author and audience. During his conversation with the audience, the narrator instructs the projectionist to ‘turn on the lights.’ Turning on the lights acknowledges that which was previously concealed (in this case the audience). The word ‘light’ has traditionally been employed as a metaphor for knowledge or revelation. The revelation in White Museum ‘s case is the audience; the filmic audience is now exposed as victims of a medium that discloses them ‘in the dark.’ In White Museum we are wakened from our spectatorship ‘trance’ which has traditionally repressed us into a passive, voyeuristic state that enforces a compliance with the manipulative, enlightened host: the screen. ‘Under the light’ the filmic apparatus is made visible and we are insistently reminded that our experience is a mediated one. As a postmodern text, White Museum thus seeks its limits and entertains its exhaustion (Hassan). In its search, it proposes change and disregards any notion of the absolute or constant. The museum is open, bare of any artifacts.

Canadian Avant-Garde Film in the 1990s by Gerald Saul

A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts, Graduate Program in Film and Video, York University, Toronto, October 1996. (Excerpt)

For the most part this film is not really a motion picture because (except for the brief silent picture of landscape spliced onto the end) it does not have any pictures. Just as Wavelength can be seen as an exploration of the zoom, White Museum is an exploration of the voice-over. The film consists of a white screen and a soundtrack. To those who understand the technical procedure of making a film, it is quickly evident that Hoolboom recorded his monologue and had an optical soundtrack made at the lab. At the time, this process would have cost $0.25 per foot, a total of $300 for a thirty minute “finished” film. This is Hoolboom’s last truly minimal film. As I hope to argue the deviations White Museum makes from the minimal film norms would mark a transition point in minimal filmmaking in Canada.

Hoolboom began making films in the minimal tradition in the early eighties. In Self Portrait with Pipe and Bandaged Ear (1981) he presented black and white pixilated images of such things as street signs. Significant portions of the film were made up of black and white frames cut between the other images. There was no movement or flow in this two minute film. In the same year he made the ten minute Now, Yours (1981) which refused to begin. The count down, traditionally ending at “2”, becomes a count up, from zero to fifty nine. This component of the film medium, the countdown, is usually hidden from the audience’s view by the projectionist as it is meant only as a projection aid. As the audience watches these numbers they think more about the projectionist and the venue in which they sit than about lack of content. This is not a new idea. American Bruce Conner used repeated academy leader countdowns in his 1958 film A Movie. Even so, Hoolboom persevered in creating variations of many tried and true radical conventions in his other early films.

The rest of Now, Yours is made up of rephotographed film and video images, many bleached and painted on. Over these images, Hoolboom’s voice tells us about his intention to show us eleven films “so brutal they haven’t been released for years.” However, he frustrates our expectations by showing none of these films. Instead he concludes with an Ontario travel film. By doing this, Hoolboom draws further attention to the fact that we are watching a film, that the form is the content. His awareness of Sitney’s definition of structural film is obvious as Hoolboom plays with each defined characteristic. He even anticipates arguments about the relevance of his films by answering that challenge in his soundtrack, “If you had nothing to say, would you be on film?”

In 1986, Hoolboom took the knowledge he’d learned and skills he’d developed about the materials of film and created White Museum. On the one hand, it is a minimal film which openly displays and discusses its own form, a straightforward minimal/structural film. However, it can also be interpreted as Hoolboom’s transition away from structuralism towards poetic films. His later films are filled with anecdotes (Mexico, 1992), psycho-dramatic events (Precious, 1994) and even scripted narratives played out with actors (Kanada, 1993). The transition Hoolboom underwent hinged on his realization of the importance of storytelling to him and to his viewers.

One of the first stories Hoolboom tells in White Museum is about film. It tells us of Hoolboom’s long-time interest in the material and processes of film. He says that his favourite time at a movie is “when the projectionist is a little hung-over so he runs all of the head leader on the screen so you see the white at the beginning and the countdown. It’s at that moment that the film is completely pure for me because it’s exactly what I want to see.” This leads us to re-read his film from five years earlier, Now, Yours, and the countdown he revealed to us there. In this new light, Now, Yours is a nostalgic look at childhood and his days in movie theatres. By giving us the tools to reinterpret his past work as subjective, Hoolboom ensures that he will not return to those forms again. If he were to make a new film with a countdown leader within it, we would no longer interpret it as a structural look at the film form but as a poetic yearning for the past.

The key element of White Museum is its clear disregard for motion picture conventions. There is no picture so there is no motion. This occurs, as Hoolboom claims within the text of the soundtrack, because he could not afford to put a picture with the film. Although he tells us he simply can’t afford to put images on the film, a more keen understanding of the materials is needed than he implies. The making of the optical soundtrack, like the one from White Museum, is usually performed by the lab as a step towards performing the much more expensive tasks involved in printing a finished film. Sound, usually from a magnetic tape, is played into a machine, vibrating a sensitive metal plate through which light passes creating photographic markings along the edge of an otherwise blank film. The film which is used for this is black and white optical film stock which is the least expensive 16mm film stock sold by Kodak. These markings, closely akin to the bumps in the groove of a phonograph record, can be retranslated into sound by the projector. As neither Kodak nor the laboratories assume that anyone would use just the optical sound film as a finished film to be released, the charge for this service is not excessive.

While one might expect that the voice without picture would be akin to listening to a record playing, Hoolboom does not allow his audience that familiar comfort. He continuously reminds them about the screen and the act of looking. He makes them look at nothing but gives them something to think about: “There is no need to make things when everything exists already.” “Hearing comes before seeing.” “If it true that a picture is worth a thousand words then why does it have to be a saying?” It is this pondering about absence which has always been the minimal film’s strength.

However, even though the audience is told that there is no image, the promise of one forthcoming (by both Hoolboom in his narration and in the years of conditioning a movie spectator has undergone in those theatre seats) glues everyone’s eyes to the screen. The anticipation of the image, when the dark theatre deprives us of any other is overwhelming. When I saw this film with a large audience in May 1995, with great effort I turned away from the screen and looked around at the others sitting there. I could see them all clearly illuminated by the reflection from the bright screen. They were all staring intently towards it. Even when the house lights were turned on in the middle of the film, as the voice on the soundtrack requested the projectionist to do, the audience was hesitant to look away from the blank screen. The theatre has created a virtual temple where the audience would not allow their wandering eyes or loose tongues to desecrate. It is quite apparent that the sound, played without the projected light, would not have captivated the audience in the same way. Hoolboom is aware of the power of the projector, citing 1960s Canadian painter and filmmaker Keewatin Dewdney in program notes a few years later: “The projector, not the camera, is the filmmaker’s true medium… The very use of the camera as a filmmaking tool has imposed the assumption of continuity on film.”

After White Museum, Hoolboom employed an increasing number of narrative story elements in his films, without necessarily relying upon all narrative film conventions. He would use the voice and the image to explore the world he saw around him instead of the limited world he saw only in the film editing room. White Museum is the transition point. In form, this film is purely structural. In content, it is both modern in its discussion of itself (self-referential) and lyrical in its wordplay and associations.