The film begins and leaves its spectators in the dark. Just a soft, male voice, which sounds like that of a fairy-tale-teller, who promises consolation and security to children who face uncanny sleep, uncanny darkness. The voice fascinates, pulls us into the film, and dictates its rhythm. But it doesn’t tell us soothing bedtime-stories: like Sheherazade, Mike Hoolboom seems to want to save himself and us from a history and a presence, from the future of an impending death sentence. He talks about a flight, and that the past seems far too torturing in the presence of a history of flight, but then again, “Why do they call airport buildings terminals?”

“You have been here all along…” The film begins and ends at the same time, as if it never existed. The title repeats the gesture when it —unrepresentable typographically—prints two thick crossed bars over the letters, as if the naming of the goal of the flight would be ‘too much.’ From the beginning, Mexico denies the images Hoolboom and Sanguedolce brought from their journey to this ‘no-image-land’: those of the young car-washers, the poor villages and booming towns, the vast cemeteries. The filmmakers have been to Mexico, but they pretend not to have seen anything. They feel like King Midas, because everything they touch (film) becomes Toronto, their home town. Like Midas, the conquistadors came to South/Middle America in search of gold, their story is documented by the Museum of Invasions, which Mexico tells us about at the beginning. Today, Mexico is still marked by the greed of the north—by its accumulated treasures that even poor artists will profit from. This is what the filmmakers realized, and they subject their very own gesture of wealth and domination to relentless criticism.

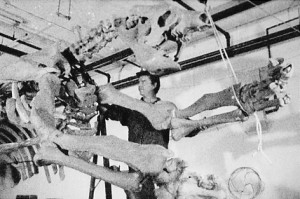

But it is not gold, they’ve been looking for in Mexico. Not possessions and treasures, but loss, lack and forgetfulness which have brought them to a presumed no-man’s-land. And thus Mexico for them—every man his projection—becomes an uncanny landscape with a ghostlike topography, Mexico the seductive protocol of a repression. Nonetheless, the monster of the past seems omnipresent, the memory of media-cyberspace a totality: Grasshoppers, over-dimensional cats, or cockroaches—which Hollywood bred in repulsion of the reality of the cold war—crowd Mexican TV screens; in its museums, dinosaurs awake to life out of piles of bones; relics remain, out of which the present creates a monstrous, imaginary past; living fish swim in the blue water of the aquariums—one fails to imagine it in the living waters of the Mexican gulf. It is as if the imagination of life is bound to fail due to the mummifications of the past.

Yet in one sequence of Hoolboom/Sanguedolce’s film, life and the fascination of its reproduction becomes an image, because the filmmakers record the work of death. This sequence stands nearly at the end of the film, yet with a duration of nearly five minutes, my interpretation of it as a key-sequence may be pardoned. And as if the filmmakers hadn’t trusted their voyeurism, they provide these images with a mask, a binocular matte. Thus, with a guarded gaze, they show us a bullfight, during which the torero is nearly killed by the animal, a horse too barely escapes the same fate. But it is the suffering of the doomed creature that seems to have fascinated the filmmakers: Yet another spear is rammed into its back, to enforce the fateful aggression, the coup de grace is the demonstration of pure dilettantism: hereabouts, the scene would bring any animal protection activist to the barricades, hadn’t the fiesta been banned already.

The work of death seems a disgusting butchery, the death of a living being endless. Again and again, the Toro assembles his last forces, gets on his legs, until finally not the torero but a helping hand applies the deadly stroke, and the cleaning team can take over. Here is more at stake than the illustration of Cocteau’s definition of cinema: “to watch death at work,” and even Hoolboom’s voice has been silenced by the slaughter on-screen. Even though the sequence doesn’t run synchronously, but has been edited rhythmically, for the first time there’s no voice-over, no music in the film. Here, the tension of the images seems to be strong enough, so strong, that the filmmakers feel the urge to distance not only themselves, but the spectator too. This is, gently put, too bad. The film is, definitely, no classical documentary of a journey, but the critical attempt to—by the means of language and the negation of image—flee touristic exoticism, but also to avoid one’s own affects. Yet the (“politically correct”) denial of such emotions deprives Mexico and its spectators of a reflexive power. Rather, like a mask, the distanciation maneuvers itself in front of our perception and inhibits what might have been exhibited: the intertwining of individual and cinematic projection. Instead of admitting the lure into scopophilia for the filmmakers and delivering it to the spectators as well, the film disavows the lure by the distanciation. The fiesta-sequence is the epiphany of Mexico: it denies the repressing force it might take to kill life, to mummify the present and repress the past, in the end: to distance oneself from passion and empathy.

The film keeps its public off its neck. Piano passages, Christian chorales and electronic music guide the spectator/listener over images and black film like a requiem over a burial. Sheherazade’s voice helps us to forget suffering and pain that had been in our minds briefly. And Sheherazade saved herself, the impending death sentence has been revoked. Yet we, the spectators, leave the movie with another sentence: “Nothing improves memory more than trying to forget.”