(Canadian Forum, 1996)

For at least a decade now, artist and filmmakers have been trying to make films about AIDS. Born into an image-soaked era, AIDS has taken naturally to film as a host site for feature-length narratives. But no made-for TV movie or theatrical feature film has quite caught the complex of panic, fear, denial and ignorance that attends the disease as powerfully as Mike Hoolboom’s Letters from Home. In this award-winning filim Hoolboom manages to capture in fifteen gorgeously explosive minutes what so many sentimental morality plays have failed to convey: the racking frustrations of being HIV positive and the persistent social confusion surrounding the affliction.

Letters from Home belongs to the growing rich repertoire of short experimental films that continue to be produced in this country in spite of and against full-length mainstream works. Hoolboom himself prefers the term ‘fringe’ both to mark the subversive nature of his art and to avoid the trap of generic dismissal. ‘Experimental’ is too convenient a term to describe a vaguely defined genre of unconventional styles, not to mention any product running under the standard ninety or sixty minute lengths. What, then, do you call a decidedly political fifteen minute film about AIDS that refuses to adhere to common aesthetic practices? ‘Avant-garde’ respect the edge of inquiry and confrontation for which the film aims, but that term too, like so many with early modern ache, ahs lost much of its linguistic power in the diluting wishy-wash of postmodern inclusivity.. If we have come to a wide understanding of what we mean by ‘fringe theatre’—alternative, oppositional, different—why not ‘fringe film?’

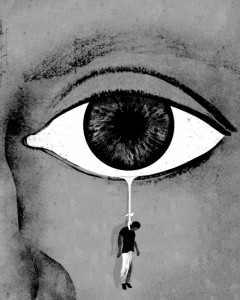

As the title Letters from Home indicates, this is an autobiographical piece. The question of labels seems especially important. Letters from Home is, among other things, a personal cry of resistance against social acts of containment, especially those that brand and stigmatize. Being HIV-positive surely changes everything-everything being identity. Hoolboom, who discovered that he had the disease in the 1980s, after he had already made a number of short and provocative films, is plainly positioned in opposition to and on the margins of healthy society. Marked by such difference, the body is free to speak its mind. Full-length features presume to have al the time in the world; short fringe films must speak with an urgent burst of declarative power. Hoolboom’s elaborately fragmented style of filmmaking, complexly textured and aggressively layered, shatters all suspicions of order and certainty. In his hands, this short non-genre, working to place matters under compression, refuses to be absorbed into the mainstream vernacular. To put it plainly, the body of the film comes to represent the body of the man.

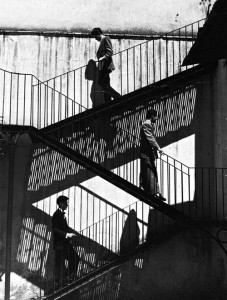

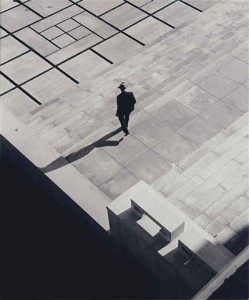

What, then, is this body? Well, it is both whole and in pieces, a series of allusive and enigmatic images underscored by fragments of song and text. Threading through these disparate representations of culture, identity and experience are voice-over readings from a 1988 speech by the late AIDS activist Vito Russo. At once cogent, angry and courageous, these epigrammatic passages carry the enormous weight of death about them, but in their performance we hear a wild defiance. A descriptive inventory of the accompanying images scarcely conveys the film’s fluid play or irony and grace: home-movie segments of a smiling child at play intercut with archival footage of exploding warships, makeshift planes and ancient automobiles; ghostly shots of civic spaces, bleached of colour and stripped of emphasis, overlap with silent bursts of flame suggesting Armageddon. If, as the film announces, “living with AIDS is like living through a war,” where is there evidence around us of the fight for research and drugs to relieve the dying? This question hauntingly informs the film, but it does not preclude the personal struggle to inhabit the fullness of life, enjoy moments of being and pleasure. Discernibly slowed-down, scratched and tainted shots of men making love under a wash of shower water assert a primal bliss that might be the cause of death itself. Each set of images bears traces not only of its own creation and selection but of its own vulnerability, trapped in time and yellowing away, but purged of nostalgia for which one requires the privilege of health.

Letters from Home adds up to a strange force of immediacy. With neither the dead end of closure or the certainty of duration, the film leaves the viewer with an odd rush of possibility, perhaps the urge to act up. This is no small thing, however short the piece. But, of course, to see it is to know what all this means.

Hoolboom has been amazingly prolific in the 1990s, making internationally acclaimed films-over fourty shorts and features (Kanada, Valentine’s Day, House of Pain, Carnival) with a fury to match his cinematic disobedience. It is unlikely that many Canadians will see his work any more than many will come to understand the politics of AIDS. One of the inspired observations in this film is that our understanding of the disease is almost entirely mediated and thereby misrepresented, a condition that leads to a wide intolerance born of fear. Paradoxically this short, frayed film attempts to destroy its own images to assert their power. There is nothing linear, straight forward, neat or untroubling about living with HIV and, as Letters from Home insolently demonstrates by example, no body of film can hope to do justice to such a condition by pretending that there is.