A Review of The Invisible Man

An Exhibition of Films by Mike Hoolboom

Then one day this infirm body stirs in the womb of God. Marguerite Duras, The Ravishment of Lol V. Stein

Mortals and immortals, alive in their death, dead in each other’s life. Heraclitus

We are blind stone.

We did not begin that way.

In our volleying pre-birth, we were abundant, a radiance of sight and light. Light combing its way through our mother’s outside skin and tunneling. Light in a home of shadows cantilevered our tumbling, blood gestured our initial patina, temperature shifted its circumference as we absorbed our growing life: food, sound, wash of oxygen, genes which penetrated our chrysalis skin and we began to absorb this flooding life through the umbilicus of our seeing skin. We were born with a corona of sight: the translucence of our initial skin. The embryo a star-child weaned on light. Was this our first affliction?

How is it that we began in an iris of darkness surrounded by so much sight and then, as if some perverse end run, we began to loose it, precipitously? Our largest organ, skin, erupted in the birth bubble as sensory being allowing light and sight to enter and register life, first in the swelling swarm of fetal life, later in the direction toward light. Much later, as sentient beings we could recall or define this luminous beginning. Do the films we gleam in science class or in motion picture theatres, depicting this burst of physical creation, remind us of some misty curtain of memory or are we fooling ourselves: images as false lanterns compensating for our forgetting? Why is it that we so often fail to acknowledge it, though we have seen the films and images our entire blind life? When we did not know, those initial nine months, we saw. Now we know, but can we see, really?

We tell ourselves we see and still we fail to remember: we cannot recall the life inside nor the passage through the first opening. We’ve constructed a cosmology of images to attend to this lacuna. Our philosophies have tried to instruct us to see before we understand or believe. We have constructed a lexicon of images to stitch together the gaps of our lives that we’re forever running backward in our memory. We attribute sight to ocular orifices. But in truth, sight began more democratically: across the entirety of our bodies. How now, flooded with so much imagery coupled with our dictatorial enslavement to what we imagine is our Rosetta Stone for understanding, have our eyes so elegantly failed to see? The kingdom of sight began wider than in the cornice of our small eyes. What has happened?

We age and metamorphose: become increasingly unsighted. We can recall, like an alphabet or algebra, all the images, real and imagined, manufactured and stumbled-upon, which have lit up the skulls of our memory, but have we admitted to our blindness. We dream in images; we speak in images, we narrate and navigate and negotiate everything through what we see or believe we have seen. Is this really seeing, or something else? Do films bespeak knowledge; do images bespeak understanding, does sight guide seeing? Are we relying upon vapors, the wavering scan of an oasis in the middle of the desert, is anything there now. How ironic that motion-picture films often use watery imagery, those slippery-looking serpents of peeling light to represent slippage in sci-fi films. Recall Terminator and the watery transformation. Don’t these computer effects look identical to heat vaporizing and rising in a desert: false water ahead. Where is our sight?

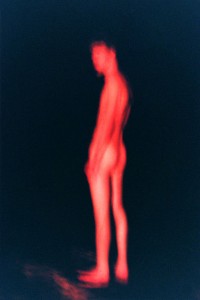

Abundant, we are born seeing and then the descent begins: our transformation. An embryo skinned in a sheath of transparent, translucent light and then what do we become? Our metamorphosis, from the entering of the outside toward the exit from the inside. Are we thrust into this waking life, from between our mother’s legs, already loosing sight and seeing skin? Is this why we require so much from the tiny moving portals in our skull?

“In the future each moment will be photographed, doubled. Our bodies will grow transparent…”

But, we were already born transparent and we slowly grew in reverse. We became opaque. Do we add to this opaqueness through our unquenchable thirst for pictures, movies, sight, or is our yearning and incessant image-making a small, quivering hope for some reunion, a returning to that which we once were? Can we capture this; elude the terrifying angels of our blindness, through constructing more and more. The shadow’s on the wall of Plato’s cave: the first newsreel, silent blockbuster, television commercial, internet ad, its all there flickering as we cower in the dark. It is all an elegy, is it not? Are we, indeed, preparing ourselves to return to our first beginning, our gradual disappearance. Have we, preternaturally, understood that images and movies are our embryonic skin projected outwardly? As Mike Hoolboom’s film “Imitation of Life” asks, have these images prepared us to learn how to die? Given us sight?

I am watching Mike Hoolboom’s films in a small room at the Art Gallery of York University and my skin is reawakening and my eyes are closing. For a moment, there is hope and a peek of a dream: to see again without the reliance of sight. The images flicker like my mother’s blue-red blood against the uterine wall. I hear sounds and howls and heartbeats. There goes another image from another film or television commercial or documentary or imagined image that I have stitched together from my own years of visual preoccupation. Is Hoolboom’s films, an ersatz memory constructed of other ersatz memories (movies) from my own life? For a moment, I do not know whether to embrace his films as his or the visual soundtrack of my own memorized life, false memories, kaleidoscopic turns, tweezed sounds and all. How has this artist, using images that others have created, stitched together my own personal memory? It is not enough to answer this easily simply because he has used clips from films and movies and documents that I have also seen and swam through. There is something more going on than collective memory. Is something archetypal happening? Is this a manifestation of our genes?

Why is it that we are always asked this question: what was your first memory? We, as a species, are preoccupied with firsts. Is this not already an indication of something failing? What was your first memory: in your life, of a love, of a friend, of a new home, of, of, of? Why do we not ask, what was your first sight? What was our first sight? We saw in the womb, we saw when we exited our mothers into that first light. Yet, we remember none of it. In the morning, we open our eyes. Who speaks of what they first saw each morning after sleep? Do we even remember that moment, each morning, the very first, ever at all? Strange, is it not, that we cannot recall the most astonishing moment of our lives, the moment our eyes peered out from the vagina opening and reconciled this startling, unprotected world. Did shock and horror blind us then, or is it something else. Why of all the moments, which we wish to see, we’ll never know that ones we must need: the corona of white light as we spiral out from the warm inside. It has become a monstrous cliché, but the darkened theatre and the conical strobe of movie-magic light against the wall: there’s the trajectory that we cannot remember. Is this why we sit there, listless, starring hour after hour, year after year at films? First the theater, then the television, now the computer, and what will be next. Will we look at each other in the future, as Hoolboom suggests, with the same dim but fully imagining sight? Memories projected onto and from within skin.

Movie magic. Wells. Mirrors. A deluge of images. Am I, now, competing with Hoolboom’s sea-tide of images, staving them off with words as a way to write myself back to seeing? Hoolboom’s films are transponders: toward and away from words, wringing and ringing the viewer. Am I collapsing or is it simply the reel is running low. From the Invisible Man, a dog’s bark is reverberating through the stretch of dark road, I begin, after seeing the movie, to hear this same dog for subsequent days. Is it the dog, my neighbor’s, really barking or have I imagined this recalling Hoolboom’s film. There is a tether there. Do images remind us to pay attention to what surrounds or have they spanner’d inside us and replaced what is really surrounding with their own soundtrack which has become the external soundtrack of our lives?

I should speak about the work.

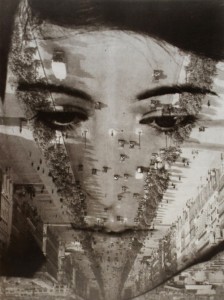

Mike Hoolboom is a hallucinatory filmmaker who has conjured up more than 30 films, although if you ask him directly, he will quickly dismiss this number. His work, like memory, is not about explaining or quantifying but rather describing and qualifying, shafts of rain elucidating the sound of a drip on tin. An exhibition of two of his recent films, The Invisible Man and The Imitation of Life (a 10-part elegy/cycle) were exhibited fat the Art Gallery of York University from November 24, 2004 until January 30, 2005. The 1st chapter, “In the Future,” the 3rd Chapter, “Last Thoughts” and the 9th chapter, “Imitations of Life” from the film Imitations of Life were exhibited along side The Invisible Man. More hallucinatory Lacanian essay then “movies,” Hoolboom’s films are rivers of images and sounds and words and palimpsests of reels of footage. Constructed from a patchwork of films which span the time of movie-making, from Vigo to Goddard, from Eisenstein to Abel, from Griffith to Busby Berkley, from Tarkovsky to Ray, one swallows his films as a cross-breed, an encyclopedic opera of movie-making which includes Hollywood entertainments, scientific documentaries, television commercials, travelogues, vintage exploration footage, anthropological studies, discarded film, home-made pictures, and his own personally shot footage, all marsala’d together to serve up a cosmology of the world’s motion-picture images. By patching and shifting and stitching together beads of images, he is both tying up and loosening our collective perception. One of the hallmarks of his work is that there is not an hierarchical alignment of images: art films coincide with Drive-In horror flicks, B-Movies are strung into art films, documentary collides with found footage from the 19th century, Discovery channel films walk with Microsoft television commercials. It is a collapsing of centripetal forces which, at last, reconstructs our own understanding of what we have not only already seen before but reinterprets what we believe we know.

An aggregate is a misnomer in describing the work. While true, the majority of the images in the films are appropriated, Kenneth Anger fighting with Sex-Ed films from the 40’s, Tarkovsky slipping inside of car commercials from the 1970’s, the remarkable quality of his technique is that his accumulated films reinvent the images that he has chosen to use, not only through their juxtaposition with different films, but strained by the entirety of the entire film he has constructed. The individual clips and loops and movies sprout a new bud. Will it be possible to see again (anew?) the films that he has chosen to cut up and breakdown, like a virus inside a cell, without thinking of Hoolboom’s films? This is the keystone to his remarkable work. The use of appropriated imagery is often hounded with weight and association. Most of the time, appropriated images are used as sly, one might say disingenuously coy, footnotes to add a measure of erudition or weight to a work. The wink-wink and nudge-nudge of the “I am so clever, can’t you see” variety. This is, in fact, not part of the experience of watching Hoolboom’s films, but the converse. His collecting changes the original images so that through his films the appropriate footage and movies gain a new weight or perspective, new humor or new grief. The original films uses have been changed by their new construction. It is rare when an artist can snatch a swatch of another artist’s work and reinvent the original piece, not through reinterpretation but through metamorphosis. Am I able to again watch the slow pan of the cinematographer’s Cyclops-eye pan, which marks the beginning of Goddard’s Le Mepris, without again thinking of Hoolboom’s use? Are Microsoft commercials really that sad? Even Vigo is reborn. Hoolboom’s films, like all films, are magic lanterns, but he is also a melancholic essayist, an Elegist. He is using and re-writing everything he has seen before.

Is not the ten-chapter song Imitations of Life a reinterpretation of Rilke’s Duino Elegies, beatifying and terrifying? Although the exhibition deconstructed this film, by separating three of its parts as stand-one loops, one begins to appreciate the mobility of the film when seen in its entirely beginning with the chapter “In the Future,” (the first film shown in the gallery) and ending with his ode to collapse, “Rain.” Are all these films and images teaching us, or are we reaching for them in order to scribble inside ourselves the memories and sight we have forgotten. If our collective memories, demarking our lives and relationships by the resurgent memory of films we’ve seen and shared with others, have become our personal memory’s DNA, it is not far off when these vapors, once implanted in our skins with microchips and carbon-based transistors and displays, our skin will be watched. We will transmit our memories, those which are mine and not yours, comprised of the same imagery, outside for the world to see. We’ve left the hermitage of the womb and moved farther away from quiet reflection to outward collective gesturing and detailing. Wait, your knee reveals the same memory of scar that I have, is that Hedie Lamar?

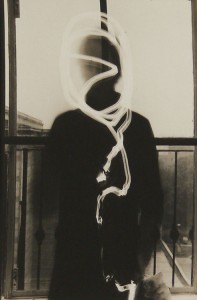

Time is not a river, though we convince ourselves it is. Bergson, whose delirium was stirred by the sway of the snake of moving images, argue this. But time is much more physical. Rivers flow linearly, time is directionless and physical: can you describe the scent of red? Time can. Is there light? Imitations of life is a beehive of digestion begun with this question of how we make, remake, unmake memory and what is all the imagery moving toward. Is it an elucidation of our inevitable projection: thin as hair, we depart and spread wide upon the air. The second remarkable chapter, entitled “Jack” is nearly totally comprised of Hoolboom’s home movies of his nephew Jack and details the lessons that he has learned from his wild-eye’d nephew: seeing, or unlearning to see. Gorgeously photographed in high contrast, saturated light and tinted wildly between sepia images bordering on the color Osip Mendelstam’s dried bee wings and the winter-tongue of cyan skin. The footage that Hoolboom’s uses, and which he himself has shot, is remarkable not only for its carnivorous beauty but as a volatile juxtaposition between that which he has chosen to create (his creation-memory) and the images he has chosen to use created by others (our creation-memory). Besides their voltage, what is also remarkable is that most of the footage, which he shot (including the digital images we later encounter in The Invisible Man) all nearly border on sightlessness. Often, he violates a fundamental principle of photography: never shoot directly into light, especially sunlight. And yet, time and time again this violation creates a profound and insightful truth: a halo, an apogee of sight surrounds his subjects: a penumbra-figure (man, or boy or shadow or flower or veil or sight) surrounded by a corona of white light. Ironically his friend, New York filmmaker Tom Chomont (about whom Hoolboom has also made a beautiful documentary) described this halo of white light as the first sight, that which we see at the moment of our birth when we slip free of our mother’s body: a circle of rounding, defining white light. The truth is that these nearly broken, restless, saturated moments which Hoolboom has shot, and appear as if we the viewer were exiting our own wombs and seeing the world for the first time, are the images in which the viewer actually sees. There, are those what the world first looked like to us.

In those brief moments when Hoolboom is shooting into light, we begin to actually understand (possibly), though they disappear quickly in burst, flickers which make up a small portion of the entire film. And yet, they’re there bleeding into our memory hours later.

The exhibition required and encouraged mobility, to sift around the room, a toe kicking in a belly, skin already born of outside life. I tumbled inside because outside mobility, walking through a gallery and watching, is not enough to replace what has been lost from the beginning. My eyes close and I begin to weep for the sight I long to have, again awakening, but cannot recover.

Does seeing teach us anything? Do our constructed images remind us or blind us further?

Then there is his newest film, The Invisible Man. It is a long recaptured elegy of a man who has re-imagined himself a child who imagines that he is trying to re-imagine what was and is and will be his memories: real or film-imagined. Again, composed of a galaxy of divergent images, it composes itself upon a critical idea: do we program the films to teach us our memories or do the films program and reenlist our memories themselves. Are your memories real or constructed elaborations on stories you’ve seen or heard before? What to do with this widening and narrowing confabulation of images: breathe, suffer, ignore, pass away? Are movies prophecies or something else, necessary markers not of what is to come but what has already happened: we are not beginning to lose sight for it has already disappeared. Still, we are there, running through the field, away from the house, down the narrow country road, across the snow-stained beach, we’re chasing, as it recedes further and further away. Of is it chasing us? We are both of and not of what we have seen.

“In the future each moment will be photographed, doubled. Our bodies will grow transparent…”

Our birthright is sight, yet how quickly it dissolves and why does it diminish? What we know is that our brain develops later the ability to categorize and demark. Jack sees something on the horizon of the distance through the window, his eyes move away. We, born of the seeing membrane, will soon in a wondrous blink of nine months, turn our cocoon inside out: our skin’s sight exchanged for birth skin, parchment, cells, hair, a malleable wall that absorbs and shields but no longer sight. Protective, this skin, we are told. Sight exchanged for something else. We are now, not then, in darkness and spend the entirety of our lives raging against the dying of that light.

We are abundance. See how vast it is that you enlarge all of space. Can we learn anything from films, from Hoolboom’s investigations and mournful songs? Is it in us to learn, maybe not. But in the end, what alas is the flight away from sight toward memory? Is it not the recognition of our not-yet-dead flight? We conjure magic from tricks and shadows what is this continued conjuring. Is it because we deceive ourselves or because we really know that our heroic striving ends without gain and continual longing. We are stirred because we are at a loss.

Mike Hoolboom’s songs are spiraling, remarkably beautiful blooms. Close your eyes and let sight enter you again. Hoolboom has begun to recapture sight through the prism of film’s hungrily devouring blindness.

So then it is true. We come full circle. We began in sight, we lost our way, we end with the illusion of sight. But isn’t the first order of seeing the attempt to transgress and transcend the absence of sight.

Time washes away stone, even blind stone.

Thus we sing, blind or not, a knotted song which eclipses the reigns of sight.

Can you see?